In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

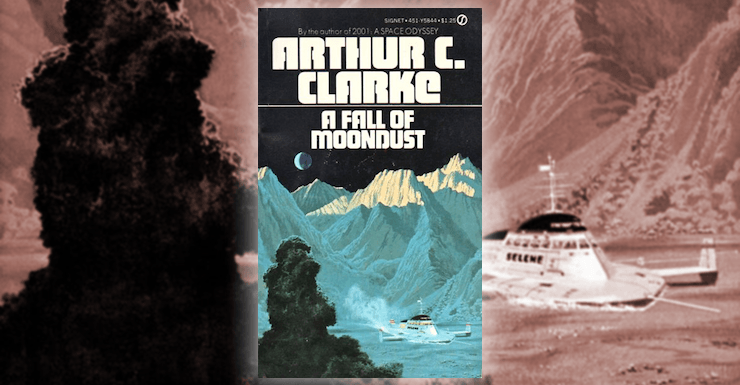

Humanity has long referred to the flattest areas of the Moon as “seas.” And for a time, it was theorized that those seas might be covered with a dust so fine it would have the qualities of liquid—dust deep enough that it might swallow vehicles that landed upon it. That led to author Arthur C. Clarke wondering if you could build a craft that would “float” upon the dust…and what might happen if one of those vessels sank. While it is rare to find someone who hasn’t heard of Clarke and his major works, there are many who aren’t overly familiar with A Fall of Moondust, a novel that helped popularize science fiction at a time when the genre was still limited to a fervent but relatively small base of fans.

As a young boy, I was fascinated by tales of the sea, and it was probably this fascination that planted the seed which eventually led me to a career in the Coast Guard and Coast Guard Reserve. While the setting of A Fall of Moondust is exotic, the narrative is very much the story of a rescue at sea. While the book was first published in 1961, by the time I read the book a few years later, the USS Thresher had been lost with all hands, and I remember that undersea rescue was a topic receiving a lot of attention in the wake of the disaster. I immediately noticed the parallels between submarine rescue and the actions described in Clarke’s book.

A Fall of Moondust was one of Clarke’s early successes, and was nominated for the Hugo Award. But it also had a huge impact outside the science fiction field, in a way that many today may not appreciate. In the early 1960s, science fiction was still a genre limited to a very small fan base. A Fall of Moondust was the first science fiction novel picked to be included in the Reader’s Digest Condensed Books series. From 1950 to 1997, these collections appeared 4-6 times a year, with each volume containing 3-6 abridged versions of currently popular books. With a circulation estimated at about 10 million copies, this publication gave the science fiction field huge exposure in households across the United States.

Clarke popularized a realistic type of science fiction that, unlike its pulp predecessors, rooted itself in realistic science and careful extrapolation of technological capabilities. A Fall of Moondust, and another contemporary book of Clarke’s I enjoyed at the time, The Sands of Mars, fall clearly into this category. And Clarke, while not religious, could also be quite mystical in his fiction; many of his works looked toward the transcendence of humanity and powers beyond anything our current science can explain. The chilling tale of the huddled remnants of humanity in Against the Fall of Night, and the story of alien intervention into mankind’s future, Childhood’s End, fall into this category, as does the novel (and movie) 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clarke’s most famous work. The space journey in 2001 starts in a very realistic manner, but soon moves into the realm of mysticism. I, like many of Clarke’s fans, often found this very moving. While I have looked to theology and the Bible for clues about what life after death might hold, the first thing I think of every time the topic is raised is a line in the movie 2010, when a transcendent Dave Bowman speaks of “Something wonderful…”

About the Author

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) is a British science fiction writer who spent his final years living in Sri Lanka. Already widely known both within and beyond the science fiction field, Clarke was famously chosen to sit beside the noted television news reporter Walter Cronkite and provide commentary during the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969.

In World War II, he worked as a radar officer for the Royal Air Force, specifically in developing radar-guided landing techniques. In an article in Wireless World magazine in October 1945, entitled “Extra-Terrestrial Relays—Can Rocket Stations Give Worldwide Radio Coverage?”, Clarke famously advocated putting repeater satellites in geosynchronous orbit around the equator. While he was not the only proponent of the idea, he did quite a lot to popularize it, and the concept went on to revolutionize rapid communication around the Earth. He was also an early advocate of using satellites in weather forecasting. In his 1962 book, Profiles of the Future, Clarke famously stated what he called his three laws:

- When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

- The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

- Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Because of their dominance of, and profound influence on, the field, Clarke, Robert Heinlein, and Isaac Asimov were often referred to as science fiction’s Big Three authors. Clarke and Asimov were both known for being top science writers, as well as top science fiction writers. In an agreement amusingly referred to as the Clarke-Asimov Treaty, Clarke is reported to have agreed to refer to Asimov as the best science writer, as long as Asimov agreed to refer to Clarke as the best science fiction author. Later, Clarke and Heinlein reportedly had a major falling out regarding the Strategic Defense Initiative, with Heinlein being in support, while Clarke opposed it.

Clarke’s most famous work is 2001: A Space Odyssey, a project for which he wrote the movie script with Stanley Kubrick while concurrently working on the novel version of the tale. He published a sequel, 2010: Odyssey Two, and participated in development of the 1984 movie adaption of the book. There were eventually two additional books in the series.

Clarke was not particularly known for the quality of his prose, which was sturdy and workmanlike, although his books frequently transcended that prosaic foundation. Besides the Odyssey books, the works of Clarke that I’ve most enjoyed over the years include Against the Fall of Night, Childhood’s End, A Fall of Moondust, The Sands of Mars, Rendezvous with Rama, and The Fountains of Paradise. Many of the books produced late in his career were sequels prepared with co-authors, and after finding a few of them forgettable, I gave up on reading them entirely. This may not be a very fair approach, but there are so many books in the world to choose from, and so little time to read them.

Clarke’s shorter works included “The Sentinel,” a story whose central concept led to the plot of 2001: A Space Odyssey. He also wrote the unforgettable, “The Nine Billion Names of God,” and the Hugo-winning “The Star.” His novella “A Meeting with Medusa” won the Nebula.

He hosted three science-based television series, Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World, Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers and Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious Universe, and was a participant in numerous other science shows and documentaries.

The awards Clarke received, and the awards that now bear his name, are too numerous to mention without exceeding my desired word count for this article. His most honored work was Rendezvous with Rama, which won the Hugo, Nebula, and British Science Fiction Awards. The Fountains of Paradise also won both Hugo and Nebula. Clarke was named a SFWA Grand Master in 1986, and he was knighted by the British Empire for his services to literature.

A Fall of Moondust

Captain Pat Harris is skipper of Selene, a vessel designed to float upon the surface of the deep deposits of moon dust that make up the Sea of Thirst (a fictional area within the real Sinus Roris, or “Bay of Dew”). She is an excursion vessel, run by the Lunar Tourist Commission, and sails with a crew of two: Harris and stewardess Sue Wilkins. Because travel to the moon is expensive, their tour group is an older crowd, made up largely of affluent people. While propellers drive her across the moon’s surface, Selene is essentially a grounded spacecraft, equipped with all the life support systems any such craft would carry. Pat is good at his job, and knows how to make the excursion as entertaining as possible.

Near the Mountains of Inaccessibility, however, an ancient gas bubble reaches the surface and Selene is enveloped and swallowed by the dust without any warning. When the vessel doesn’t check in, a search is initiated. The lunar colony calls upon the Lagrange II satellite, and astronomer Thomas Lawson takes on the task of locating the vessel (upon my first reading, I had yet to understand what Lagrangian points were, but this is an early use of the concept in fiction). Lawson finds no sign of Selene and goes to bed.

On Selene, Pat is working to figure out what happened, and what the implications are, when a passenger approaches him. He is Commodore Hansteen, noted explorer and leader of the first expedition to Pluto, who had been traveling under an alias in order to avoid attracting attention. While there is no formal transfer of command, the younger, grateful Pat is happy to defer to the older, more experienced man. At this point we meet the passengers, and if I have any criticism of the book, it is that they are a rather predictable lot (although Clarke, commendably for the time, does introduce us to physicist Duncan McKenzie, an Aboriginal Australian, making the cast of characters at least slightly more diverse than one might expect in 1961). They are understandably worried about their air supply, but soon realize that their main problem is heat, as the normal means of dispersing excess heat are now compromised by the dust.

The lunar colony sends out smaller dust-skis to trace Selene’s route in an attempt to locate her, but find nothing. An observatory reports a quake occurred in her vicinity, and they suspect that she has been buried by an avalanche, which would probably have destroyed her. Fortunately, circulation in the dust draws off some of the waste heat, and while conditions are unpleasant, the passengers are able to survive. Meanwhile, Lawson awakens and begins to look for traces of the wake Selene should have left, which would be visible on infrared cameras. He finds a hot spot caused by their waste heat, and realizes what has happened.

Buy the Book

The Consuming Fire

On Selene, the entertainment committee decides to have a reading of the old cowboy novel, Shane, and Clarke has some fun speculating on what future scholars would have to say about the (then popular) genre of the Western novel. Elsewhere, Chief Engineer Lawrence realizes that there may be a chance to save the passengers and crew, calls for Lawson to be brought to the moon, and begins planning a rescue. Lawson is an unlikeable fellow, but it is enjoyable to see him rise to the occasion and become a better man. Lawrence and Lawson set out to look at the hot spot, and eventually find the ship. A metal probe not only locates the ship, but allows them to communicate by radio.

We get a sub-plot regarding press efforts to uncover what is happening, as well as various sub-plots regarding the tensions between passengers—including the reveal that one of them is a believer in UFOs (Clarke uses the opportunity to poke some fun at them). But what kept my attention riveted, both as a youth and upon rereading, was the engineering effort of building rafts and structures to anchor over Selene and provide them with a new supply of air. The failure of their CO2 scrubbing system adds significant tension to that effort, providing an urgency to the rescue effort that no one had foreseen. Additionally, attempts to build a tunnel to Selene using caissons are complicated by further settling of the vessel. The final complication involves a fire in the engineering compartment, which threatens to explode and kill everyone aboard.

That the crew and passengers survive the ordeal will be no surprise, but for those who might want to read the book, I will be silent on any further details. I would definitely recommend A Fall of Moondust as a solid adventure book, with the narrative driven by technological and scientific challenges. It is an example of the realistic approach that made science fiction stories respectable and more relatable to wider audiences. The book is an early example of space rescue tales, paving the way both for works based in non-fiction like Apollo 13 and science fictional stories such as Andy Weir’s novel (and eventual movie) The Martian.

Final Thoughts

A Fall of Moondust was a pioneering book that made the exotic seem almost inevitable, leaving readers with the impression that it was likely just a matter of time before tourists would be buying tickets to the moon. Fortunately for lunar explorers, while moon dust turned out to be a real thing, and a pesky substance to deal with, it was not found in sufficient quantities to swallow up any of our expeditions or vessels. Clarke was able to produce a science fiction adventure that was gripping and full of technological speculation, while at the same time straightforward enough to appeal to the many subscribers to Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, many of whom may have been encountering science fiction for the first time with this tale.

And now it’s your turn to talk: I’m interested in your thoughts on A Fall of Moondust, or Clarke’s other works, as well as your thoughts on his place in the pantheon of science fiction’s greatest authors.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.