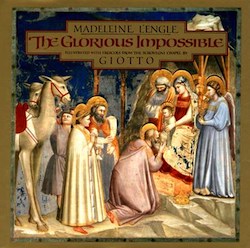

The Glorious Impossible (1990) is Madeleine L’Engle’s retelling of the life of Christ. Intended for children, and illustrated with reproductions from the Scrovegni Chapel frescos in Padua painted by Giotto di Bondoni in the late Middle Ages, the retelling begins with the Annunciation and the Nativity and ends with Pentecost. It’s not exactly a Christmas book, but it does discuss Christmas, which is why I’m discussing this book out of publication order. (I did mention that L’Engle’s books create a problem with time.)

For many people, I suspect the main attraction of the book is less the narrative, and more the Giotto paintings. The reproductions are superb, and for those who haven’t had the chance to travel to Padua, and even for those who have and found that the experience made them feel very short and unable to see the upper paintings in detail, the book presents a splendid opportunity to see the paintings—most of them. Giotto’s original focus was the life of the Virgin Mary; L’Engle, more interested in the life of Christ, leaves out the pictures focused on the early life of the Virgin. I found myself fascinated by the little details in Giotto’s paintings—Joseph’s completely exhausted look; the way the Wise Men get halos while their poor servants, focused on taking care of the pack animals, are left without any halos at all (poor servants) and the look on Judas’s face, as if he just knows he has to suck the life out of everything. This is great stuff.

(Also, Giotto’s painting of Lazarus emerging from the tomb? I still want to know how he’s managing to walk swathed in bandages like that. At least with Hollywood mummies the legs aren’t bandaged together.)

On the other hand, these Giotto paintings do somewhat constrict L’Engle’s retelling: she can only focus on the two miracles Giotto chose to paint (the Wedding at Cana and the resurrection of Lazarus) although other miracles are mentioned in passing. Similarly, she says very little about Jesus’s preaching and ministry, since Giotto didn’t paint that in this chapel. And the paintings sometimes give an odd tenor to her statements, as in this quote from her:

In Scripture, whenever an angel appears to anyone, the angel’s first words usually are, “FEAR NOT!” which gives us an idea of what angels must have looked like.

.which appears right next to Giotto’s illustration of the angel Gabriel, who looks just like a lovely, straight nosed human, admittedly with red wings—but otherwise, not particularly terrifying. More problematically, in the account from the Gospel of Luke, Mary is less terrified by the appearance of the angel and more terrified at what the angel is saying, which she correctly guesses is not going to be universally believed.

But these narrative asides also provide the most interesting parts of the text for those interested in L’Engle’s religious beliefs, and how they may have shaped her fiction. Some of these asides are quite straightforward—L’Engle’s explanations of certain aspects of ancient Jewish life, or her statement that having older friends who are not parents can be helpful, and so on. Some are somewhat awkward— for instance, her comment that 20th century atrocities hardly excuse Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents, which, well, yes, with the slight problem that the 20th century atrocities actually happened and Herod’s Massacre is historically dubious (but painted by Giotto) although Herod’s murder of his own sons is less historically dubious. (In this book L’Engle appears to accept all of the New Testament stories without question, regardless of their historical probability.) The entire discussion of these atrocities suggests that L’Engle was still struggling with reconciling the horrors seen in her lifetime with her belief in a loving Christ, and that particular page is left with an ambiguous ending.

But her most interesting comments come when she inserts discussions of science into her text, particularly telling in her description of the baptism of Jesus, with this paragraph:

We human beings seem quite capable of accepting that light is a particle, and light is a wave. So why should it be more difficult for us to comprehend that Jesus was completely God and Jesus was completely human?

I’m not entirely certain that all human beings are capable of accepting that particular quality of light—but this goes back to an insistence that L’Engle would return to again and again: science and religion are not opposites, but complimentary, and that the study and understanding of science should bring people closer to God.

The retelling is filled with questions, and L’Engle does not claim to have the answers. What she has is an abiding wonder that a creator God would become human—a wonder that allowed her to create in her fiction stars that became angels, time travelling unicorns, and the ability to travel to other galaxies and inside a mitochondria. I cannot recommend this book for casual readers. But for those interested in Giotto’s frescos, or for those interested in an easily accessible summary of L’Engle’s theology, this may be worth a look.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida, and will be heading back to publication order for the Madeleine L’Engle reread next week.