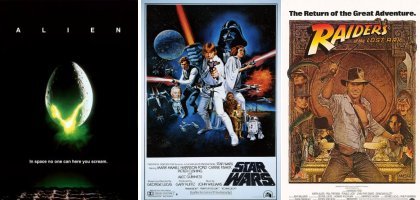

I was born in the mid-1970s, and came up watching movies in what quickly became an amazing time to be a sci-fi fan. Viewers were treated to an ever-marching parade of awesome SF flicks: Alien, Aliens, Close Encounters, E.T., the original Star Wars trilogy, Blade Runner, Star Trek II . . . it goes on and on. These movies had great stories and characters. They also had great eye candy—visual effects.

Man, do I loves me some eye candy.

Of course, much of these groundbreaking VFX hailed from breakthroughs in technology: a combination of model-making artistry and computer-fueled motion control camera work, and crazy-convincing mashups of matte paintings and rotoscoping. It was tedious, expensive work; nearly all of it was meticulously crafted by hand, using real-world cameras, sets, paint, explosives and glued-together models.

This stuff was also strapped by real-world compromises and technological limitations. Those glory years were filled with real “bubblegum and chickenwire” stories; the “M” in ILM should’ve stood for MacGuyver. And yet, a hearty chunk of me still finds these effects far more convincing than the superior VFX technologies filmmakers now have at their disposal.

You’ll likely call me a nostalgic proto-curmudgeon, but bear with me. I’ll cite Star Wars. I’ll take the speeder bike chase in Return of the Jedi over the pod race in The Phantom Menace any day. Same goes for the stop-motion AT-AT snow walkers in The Empire Strikes Back over whatever the walking tanks were called in the prequel trilogy. Same goes for the hand puppet Yoda, versus the its frog-hopping pixel-powered prequel version.

Why? Because, as anachronistic as it sounds, this stuff looks more “real” to me than the newer stuff—and it’s that “reality” that cements my belief in those fantastical worlds. I believe this buy-in hinges largely on those old school limitations: the necessity of physicality; the demand that a thing be built before it could be filmed. The effects actually occupied real space, had literal dimension, and obeyed familiar (and completely unconscious) audience expectations of gravity and physics.

Take the Alien movie franchise. The first two movies were packed with skinny dudes in monster suits and—in the instance of the awe-inspiring Alien Queen—on-set puppeteers. Completely believable. Why? Because those were real shadows those actors were casting; those were real glimmers of light against their costumes. In contrast, Alien3 sported a rod-puppet filmed against a blue screen, an obvious post-production addition. (I admired the creative intent of showing a “new” version of the alien . . . but the design and execution were deeply flawed.) By Alien: Resurrection, we had full CGI Fakey McFakerton swimming aliens . . . and the Alien Versus Predator flicks were crammed with so much ill-conceived, physics-defying full-on CGI, I pined to see a zipper in the monster suit.

I’ve mentioned Star Wars. Poor Jar-Jar Binks has suffered a decade’s worth of ire. I didn’t mind the character much; he was there for the kids, he was funny. But despite the filmmakers’ best efforts, the creature was a walking film-flam cartoon; obvious CGI. His visual execution was a distraction. His lack of being “there” in true three dimensions undermined his believability. It created a visual, and emotional, disconnect.

(I’ve wondered at length if the great Jar-Jar backlash unconsciously stems from this. We wouldn’t grief this character if he appeared in a Star Wars cartoon, book or graphic novel—but his obvious visual incongruity spoils every scene in which he appears.)

Ever watched the recent Mummy movie series? They’re great popcorn flicks; adequate Indiana Jones wannabes. But few of the CGI effects failed to suspend my disbelief. This wasn’t because of their ambition (which was world class), but because their execution came up short. Dude, just give me a talking animatronic mummy or Anubis warrior. I can totally live with a talking puppet, as its presence provides visual continuity within the scene. It matches light, shadow, and depth of field because it’s real.

And speaking of Indiana Jones: The first three movies had some delightful old-school visual and optical effects (Nazi face melting for the win!), and real-life stunts. Compare that to the CGI-fueled swordfight / chase sequence in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull’s South American jungle . . . and the infamous vine-swinging Tarzan moment . . . and the temple-wrecking climax. Those sequences were more than death-defying—they were physics-defying, filled with feats normal humans simply can’t do. It was unnatural to our peepers.

I’m convinced that this unreality, whether we consciously recognize it or not, pisses off our brains. And when our brains get fussy, the story is doomed.

This isn’t to say that great old-school VFX occurred solely in the 1980s. Independence Day wasn’t a thinking man’s movie, but the filmmakers used real models for those spacecraft (including a full-size alien fighter, the ultimate in space-occupying “realness”), and real miniatures of the White House, the Empire State Building and other buildings in their city-wrecking sequences. When those skyscrapers went boom, that was real debris hitting the camera. You can’t beat that with a stick.

And this isn’t to say there aren’t movies with CGI that seamlessly—and thereby effectively—sell the fantasy. Terminator 2. The Jurassic Park films. Serenity. The freeway chase sequence in Matrix Reloaded. Starship Troopers. Iron Man. Transformers. (But not its sequel.) Of course, the very best CGI effects occur within full-CGI movies—WALL-E and The Incredibles specifically—because our minds actively alter their expectations when we see animated films.

In fact, I believe that’s what this boils down to: our brains and expectations. Our brains crave congruity—a commitment to dimension, depth and heft. I completely understand how supremely difficult it can be for VFX crews: They’re expected to bring a convincing performance and depth (and depth of field!) to a bunch of 1s and 0s. I also understand why directors want to defy physics and belief with these animated sequences—set the camera wherever you want! Come up with something entirely new!

I argue this newness may do more harm than good. Our brains get fussy.

I fully know that modern filmmakers cannot go back to those old-school VFX techniques. But there is great visual wisdom in those now-classic movies. If effects can feel as if they convincingly occupy the same space and look as the rest of the story, they can lend credibility and an equally convincing presentation to that story.

If moviemakers using CGI can do that, then this proto-curmudgeon will sing a different tune . . . and will buy whatever they’re sellin’.

J.C. Hutchins is the author of the sci-fi thriller novel 7th Son: Descent. Originally released as free serialized audiobooks, his 7th Son trilogy is the most popular podcast novel series in history. J.C.’s work has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post and on NPR’s Weekend Edition.

Spectacle is not special unless you have to work for it.

Programming may be a lot of arduous hours in front of a console but it lacks the concrete reality of physical effects and stunts.

Where are the museum pieces and walk through experiences for CGI effects?

Not only did physical effects give a weighted sense of reality to the film but it generated magazine articles about how it was accomplished and left behind physical property that people clamor to see when it is set up in a museum or goes on tour as an exhibit.

Few people want to see the workstation that processed the CGI for Alien 4 but many people want to see the Alien suit from the first movie.

I agree with your assessment of visual effects and just want to add that there is the additional value to history and entertainment when the physical effects are preserved and showcased.

Word. Just word.

One of the best examples of the seamless integration of physical and digital effects is Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Part of this is a result of the digital and physical effects being handled by he same company and a preference by the director for physical effects first.

Look a bit further back to movies like the original War of The Worlds, The Day the Earth Stood Still, the movies featuring Robby the Robot and others. They looked real, because the spaceships and so forth looked like real objects.

I will make an exception for the cheesy effects (Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon I think) where spaceships apparently were powered by sparklers.

I agree with just about everything said. I think most of the problem is that for a long time CGI was used when it just wasn’t good enough. Chewbaca even though you could pick apart the costume and see that the mouth didn’t look all that functional, you knew he was there. The lighting was right, his hair looked like hair and all the lighting on that hair looked like real light. If you look at the texture of someone like Jar jar, his skin doesn’t look real, it doesn’t look close enough to how an animal of that types skin would look in the situations he’s in. If you compare the realness of say the CGI jar jar and Yoda to the CGI general grievous grievous IMO looks almost as real standing still as a model of him would. Because the textures on his body and the smooth already artificial shapes are easier to make look realistic via CGI.

Where as old yoda vs new yoda. Well the old yoda couldn’t move well and his expersions weren’t as detailed as CGI can get. but again he looked much more realistically textured and placed.

I think steelBlaid is right lord of the rings did a very good job at blending the two and i think for fantasy and sci-fi which is not animated but meant to be realistic looking at this point a blend is still the best, favoring real models where feasible. However; it is really getting to a point where the balance is starting to turn and soon my arguments will be outdated lol

My initial reaction is to agree with you that puppets or “real” effects often give better results but a large part of this is that it removes a layer of acting that the other performers in a scene have to do. Laura Dern talked about the scene in Jurassic Park where her character walked into the clearing and saw the sick triceratops. She said, “There was no acting there,” because they had kept her away from the area where they were going to be filming and had the puppeteers well-hidden. When she walked into the clearing, she saw a sick triceratops where she had expected to see the usual green sign that said “triceratops eyeline.”

The rest of what you are talking about is the uncanny valley. It’s something that we have to fight in puppetry all the time. As you pointed out, if the brain knows it is stylized it accepts it as make believe and is happy. If it is close to real, then every little thing that’s not right sticks out as unnatural and hence dangerous. It’s the thing that helped us spot camouflaged animals in the wild.

New Yoda is a good example. The prime thing that’s wrong with him is that his facial features move too much. Watch yourself in the mirror as you smile. Your skin moves, but not with the bizarrely detailed wrinkling and curling that his skin does.

The catch to all this is that these are examples of CGI that has failed. When it works you don’t see it. It truly is seamless. Guilarmo del Toro is very good at blending practical effects with CGI. Pan’s Labyrinth has a fair amount of CGI in it, but it blends beautifully with the world of the set. The Matrix series is also heavy on the CGI and again it is pretty darn seamless.

One of the things to remember is that this field is still pretty young and changing very fast. The things they’ve been doing for twenty years, like space flight, looks darn good. We’ve been only about ten years and if you look at the first ten years of cinema, it was equally crude. The difference here is that the crude technique looks slicker.

give me a real explosion over a CGI one anyday…

Believe it or not. I’m a part time 3d modeller (and Free lance, too), I did try to get in the Movie business. But I wanted to this years Nano written back then!

During my short time at uni, I did SFX. Despite having access to the same kit, one group did CGi heavy piece, which was mainly a long continuous shot of a space station to a room with a holo projector, with CGI Backgrounds. The Projector was the only actual Prop, but was powered by a another animation. The only other one that used CGI created a model and then “blew” it up. (We couldn’t blow up stuff, due to health and safety.)

The rest used Green Screen and made sets, including a Miniatures. Actually the green screen was ours, but our filming had be done first since we couldn’t actually build a set we wanted in the space we had. We still had to do 3d model of that room after that. Both “models” fit the Mantra if it’s not setting the scene, it’s plot point.

It really takes ages to mimic Skin, Fabric and Hair well. Hair is a nightmare, but it’s getting better. Skin is hard to get right due to the skin has a bit transparency, and it’s hard mimic under that.

Model making needed to be done before the day of filming. CGi can be done after filming.

I saw this sort of issue recently in a couple of trailers on “Film 2009” (UK film programme). One was for 2012, where the clip seemed like an endless series of just-in-time escapes (eg getting the plane off the ground as the runway cracked apart) that you could see was so CG micromanaged it lost all tension.

Another was a clip from Amelia, where the title character crashes a plane. A wing tip just sweeps by a camera tracking across the runway in front of the plane, some other part of the plane just sweeps by another camera. I assume it is VFX but even if it was done in camera it looks too tightly choreographed to be real. It’s not the technical quality of the effects work at fault, so much that real cameras or POV people wouldn’t or couldn’t have been there.

There’s a shot in Apollo 13, iirc, where the just-launched Saturn V rushes past a virtual camera impossibly dangling in mid-air that would have been just a few – implausibly dangerous – feet away in real life, which spoiled the sequence for me. There are similar shots in The Aviator, where planes zoom right up to some camera apparently hanging in space like a christmas bauble, thus revealing themselves as empty of metal and full of numbers.

As for the all-CGI environment, I once visited a friend while he was at Pixar working on A Bug’s Life – he was an old-school real-world cameraman, and his job amongst all the young computer animators and technical directors was to lay out plausible real-world camera moves as if a real heavy camera was sitting on and constrained by real tripods, dollies and cranes (and, presumably, what would have been the real physicality of the props and characters)

Convincing digital creatures are problematic, even now. And if you’ll excuse the self-promo, I even did a short story for Interzone on this topic about ten years ago (apologies for any technical gaffes). Animals badly filmed on cheap lo-res video cameras usually still look more real (cos they are real) and integrated into their environments than lovingly crafted and lit CGI creatures with hundreds of hours spent on them.

It’s worth looking at some of the old war movies for amazing special effects — epics like “Tora! Tora! Tora!” and “A Bridge Too Far” spring to mind. In those days, if they wanted huge explosions they just used to really blow things up. In “Bridge Over the River Kwai” they built a massive bridge over a gorge, sent a real steam train over it, then blew the bridge up so that the train fell into the river. Not the sort of thing where you can do a second take!

Floyd C @@@@@ 4:

I second the original War of the Worlds, when I saw it first I couldn’t believe that it had been made twenty years before Star Wars.

And, re Tathel’s point, use of CGI when it isn’t good enough: that bit in the first Harry Potter film when he fights that monster in the toilet, or the much-vaunted fight sequence in the second Matrix film between Neo and the dozens of agents. Both were shite.

Bring back stop-motion visual effects, those clay-mation monsters from the old Jason and the Argonauts movie still look bad ass.

I’ve always thought it was unfair that Moonraker is considered one of the worst of the James Bond movies. It had some truly amazing special-effects, that were done on a shoestring budget and managed to look like they cost ten times what they actually did.

The special effect for the space shuttle launching (which had at that time not yet happened in real life!) was accomplished by filling the hollow space shuttle model with salt and filming it trickling out. Yet even now it still looks real.

The outer space stuff was done entirely in-camera: they block out all of the lens except a specific part of it, film something in that part, run the film back, block out everything except another part, film again. Amazing stuff, and excruciatingly fiddly.

I disagree about LoTR. I hated several of the CGI monsters and despised the Galadriel CGIification.

CGI has its place and frankly, without it, some movies would not be made for another 50 years. I won’t live that long, so I am thankful for what we get. One movie that tried to do a totally different thing that hasnt been mentioned was Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. Although it wasnt a successful movie, how can you argue with a movie that has Giant Freaking Robots! ;)

I agree with the premise of your article, but its a work in progress. Next month may be the next generation of CGI, with the opening of Avatar. (btw, preview of story line looks like it sucks but the visuals look amazing)

I’d rather have weighted physical models touched up with CGI than all-CGI which does tend to fall short. It’s a work in progress that offers a lot of potential but it gets abused.

I admire actors that can fake reactions when looking at nothing more than a tennis ball and a green screen.

I still believe in the TMNT from the first movie. The only reason I didn’t crawl down a sewer to hang with the guys is that sewer lids were too heavy for me to lift!

I really don’t have a whole lot more to add, other than that the main thing that CGI gets wrong time after time after time is the simulation of basic physics. It would take a volume to describe all the things that go wrong, but let’s just take ballistics: when things rise and fall and hit the ground and bounce, it’s wrong. It never looks right; certainly nothing I’ve ever seen on film does. In CGI it’s either too clean and pure, or the accelerations due to gravity are all wrong; maybe they’re not taking air resistance into account. I don’t know. And when things bounce, the elasticity is just not right. Film a bowling ball or a baseball hitting the floor, then watch a CGI version. It won’t look the same.

I have a feeling that it’s a computational complexity thing: real systems are just composed of too many bits. To build a computer model that does the simulation accurately and run it on for each object in a CGI animation would require so much computational power and time that the film would never get finished. So they take shortcuts, and these invariably seem to fail.

I agree, and would like to chime in from the horror movie perspective. Horror directors have discovered CGI gore, and it’s just horrible. There’s a scene in Midnight Meat Train where an eyeball gets knocked out, and it’s all done with CGI and it looks phony as hell. Give me some latex and karo syrup any day.

CGI is still reaching maturity. A lot of time has been spent on photorealism and details like shadows and lighting are obvious areas where improvements will be made. But many stop-motion and puppet effects have lots of problems as well, however people don’t hold them up to the same standards. “Oh, the shadows are wrong, he looks like he’s not in the scene”. Sure, but those darn puppets don’t look like they’re alive at all.

The other problem, as some have mentioned, is the Uncanny Valley. This is an increasing problem in CGI because people will dislike certain effects, even in animated films. Consider The Polar Express, which had amazing artwork, but the people all looked like they were blind and staring off into space. It was very disturbing.

In time CGI will reach a level of realism that is indistinguishable from reality. You’ll still have improbable physics or bad camera angles or bad lighting, but you have that already even with mundane effects. The choice of technology isn’t going to make up for poor directing.

The freeway chase sequence in Matrix Reloaded wasn’t CGI, it was a real stunt, although done so well everyone thinks it was CGI, making the stuntmen sad. (The ghosts were CGI of course.)

Kevin Conley’s The Full Burn is a fascinating look at Hollywood stuntmen (and women), old and new, including a detailed discussion of the most impressive stunt ever, done only twice.

I greatly prefer films where CGI is only used to enhance the visuals, not replace them (and all too often, replace any semblance of plot or characterization). In my eyes, Ink and Pan’s Labyrinth get this right, 2012 and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow fall very flat.

I liked Sky Captain, by and large, and think it worked fine because it was all stylised – the acting, the effects, the settings, the props, the plot – so it all seemed cut from the same cloth.

The problem with too much realism in CGI is that it often tries to cross the uncanny valley, but doesn’t succeed. If everything, shape, texture, lighting, movement (especially movement) is not exactly right, then it feels wrong to the audience, most people can’t quite put their finger on why, but people who know traditional animation principles usually can.

Maybe one day, they’ll have a simulated actor so realistic it will fool everyone, but is it worth it? There’s a reason 3D animation people have moved away from realism into a more cartoony look and feel.

I’ve seen profiles of James Cameron making Avatar, obsessing about one individual muscle attached to a CGI character’s eyeball, the reflections on alien skin, and so on. Then I see the previews and yeah, the animated faces look more expressive than most, but they’re still Saturday morning cartoon characters. The way they move, flex, react, is inescapably programmed. Skinny people in monster suits would have been better. As you say, easier for the brain to accept as existing in the real universe.

There’s some satisfying lesson here about hubris, value engineering, and the triumph of material craft. Years from now it will be the stories that people return to, not the dated SFX. There are a million old movies with crappy rear projection effects, but some of them are all-time classics in spite of it, and everybody just ignores the obvious fakery.

I completely agree with the sense of tactility that is missing in most CGI films. This was the number 1 reason why I was so looking forward to “Where the Wild things are.” While I was let down by the acting of the wild things (this is a topic for a completely different message board), I still loved the idea of dudes in furry suits actually walking around and MOVING space. Alas, Jim Henson is no longer with us making whacked out movies like “The Labyrinth” which I would watch 50 times before I go see Tim Burton’s Alice and Wonderland movie which looks just so… not right.

I have noted before that LotR failed noticeably in Moria; masonry structures crumble at the point of high load (closest to the ground) at the very least.

And I second NomadUK; not much annoys me as much as movies or video games with flat trajectories for thrown objects. The best ballistic arc I recall is Mr. Incredible taking out a guard with a thrown coconut.

btw, I like the spell checker- it can’t tell you to use “loser” instead of “looser”, but it does recognize Moria!

I completely agree with the point of the article. In general models and puppets did look better than CG. CG is definitely a very valuable technique to have, but I wish it weren’t being used for every situation these days even when the older techniques would have achieved a better look. You mentioned Terminator 2 as a movie that had good CG effects, but it’s important to note that T2 used plenty of old fashioned effects, with CG applied judiciously. For instance, they had costumes with metallic “dents” for when the T-1000 got shot. The liquid nitrogen truck that crashed at the end of the movie was a model. Stuff like that. I think the combination of conventional and CG effects they used there would still be the best way to go today, but now it seems like almost everything is done with CG.

I just want to give a quick shout-out to Army of Darkness as the last of its breed. It couldn’t get made today without CGI (cf. Drag Me To Hell) and it wouldn’t look nearly as good. (Ibid.)

The best CGI I’ve seen has almost always been on TV rather than film, mainly because on film they usually had the budget to use models or other techniques but went with CGI because it’s easier. BABYLON 5 and BATTLESTAR GALACTICA had no choice but to use CGI, and because their sfx budgets were not large they had to make every shot count, often resulting in shots that are very impressive because they have to do the job of an entire ten-minute CGI assault on the senses from say a George Lucas movie.

The CGI-driven assault on New Caprica or the battle sequence in the B5 ‘Severed Dreams’ episode look infinitely superior to any space battle from the movies in the last decade simply because they had less to work with, and made every moment count, whilst the likes of the STAR WARS movies had too many options, no limitations and drowned the screen in confusing mayhem.

Amen to all that. You could have gone even further on Star Wars, though. I remember watching the original (true) trilogy on TV when I was a kid, and that is a defining memory of my childhood. So, when I bought the remastered edition on DVD not long ago, I was really stoked, and for the most part it was really great. Except that Lucas had to go and insert CGI in each of the frigging movies !! You can spot it a mile away, and I can’t help but cringe each time that happens. Talk about desecrating a work of art.

The best CGI I have ever seen was on Battlestar Galactica (the revisited series, of course), and most of all District 9. I was shocked how much believable the prawns looked, totally integrated into their environment and at the same time, extremely expressive. This movie rocks in so many ways.

A particular problem with CGI is the loss of the subconscious.

When a person is doing things, there are conscious movements, but there are also many subconscious movements and expressions. You don’t think through every movement you make, and as you converse, there are many subtle cues than neither you nor the person your with think about, but which convey emotion and information.

A skilled puppeteer (such as for old Yoda) works the puppet intuitively, and can and will convey such subconscious expressions without having to think through each eyebrow twitch. Experience with the puppet includes development of a complex range of expression.

With CGI, as far as I can tell, there is no real way for the creator to react and express through the on-screen character in real time. There is no subconscious, nothing on the screen if the artists don’t consciously plan and program it. So you loose the realism that comes from a real-time performance, and you loose the expression that comes from human beings (the puppeteers) interacting.

I agree. CGI should be used like make up. If movie makers do that, well then, wouldn’t movies be better? After all, good make up enhances a character not distracts. A subtle tweak here and there would be just fine, but throwing the whole pancake on just because the jar is full, seems silly.

Sure, there are times when the full force of CGI would work just fine, but then we know that is what we are looking at. Trying to fool folks into thinking this is all real with an over load of CGI leads to crappy movies.

CGI is a cool tool, but not the only one in the box.

I agree CGI will never be as realistic as the old models/puppets or stunt men in costumes,i think they reached a peak in effects in the 70 s and 80s and its taken a backwards step now,they should go back to the old methods even though it was much harder work,and use a bit of CGI to touch up .

Im with you on this one, JC. I grew up in the 80s and find the model visual effect much superior and realistic than CGI. One problem with latter is that its overdone. At least they could do a mashup of models and CGI but I guess the ever decisive factor these days is affordability. One example where CGI somewhat worked was in the later seasons of Star Trek Voyager.

Hey JC – you speaketh true. Like you I grew up in that golden age of pre-CGI movie magic, and for much of the 80’s I worked as a professional model maker – on a few films and commercials but alas mostly for the non-entertainment industries. I had zero interest in trading the tools, plastic and paint for a computer workstation and as the demand for modelmaking faded with the ubiquity of cheap (and often cheap-looking) CGI I went elsewhere. Most movie effects of today leave me cold. They look like exactly what they are: thins souless creations by over-sugared and caffeinated computer nerds. Depsite their sketchy history in the realm of special effects, I really think the Japanese had a better approach to integrating computer technology into the effects field in the last 15 years. If you watch the last few Godzilla movies, they are very nice pastiche of the traditional suite-mation and minatures, with very effective CGI sweetening. The overall work is (as always) uneven, but I’ve seen some incredibly impressive work done this way in that series, much more tangible and visceral in look and feel than the sterile CGI pure-play that US effects houses favor.

??ldi foods food market mn Questions and Answers

The Hollywood Walk of Fame stretches cheap nfl jerseys,

over the sidewalk from Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street in Hollywood to La Brea Avenue. Over 2,000 stars comprise the Walk of Fame, which was created in 1958. At the start, http://www.danreedconstruction.com/#fii,

stars could receive multiple stars for separate performances, however nowadays the Walk has a tendency to honor stars not previously cheap nfl jerseys,

that comes with the Walk. Nowadays, an average of two celebrities are awarded a star month after month.

The Walk of Fame was designated a Historic Landmark in 1978, and countless tourists go to the Walk of Fame on a yearly basis to photograph the celebrities cheap nfl jerseys,

of the favorite celebrities. The initial star was awarded to to Joanne Woodward last month 9, 1960. Each star includes the honoree in bronze http://www.seawaycommunications.com/#dsc,

as well as an emblem designating the medium which is why the celebrity is being honored. The emblems add a movie camer for film, Tv Cheap nike nfl jerseys,

for television, phonograph record for musicians, a microphone for radio as well as the comedy/tragedy masks for stage acting.

Recent construction about the Cheap nike nfl jerseys,

Walk of Fame renders it essential to remove certain stars, which might be being stored in seawaycommunications.com/#hhv,

an undisclosed location until they might be returned with their places around the Walk of Fame. Security camera systems watch over the Walk of Fame, but such safety measurescheap nfl jerseys,

have never prevented thefts. Thus far, four stars are already stolen, including that relating to Jimmy Stewart, Kirk Douglas, Gene Autry and Gregory Peck.

Stolen stars are actually replaced, and cheap nfl jerseys,

upkeep of the Walk of Fame is undertaken with the Hollywood Historic Trust.The newest honoree was actor Roger Moore, who received his star on Oct. 11, 2007. Moore is best renowned for starring in seven James Bond films from 1973 to 1985. Moore star, appropriately, is located at 7007 Hollywood Boulevard.

Preppy is usually a term that’s both a noun as well as an adjective. cheap nfl jerseys,

Preppy term was in fact coined in case you attend prep school currently madness of Preppy is almost different. Cheap nike nfl jerseys,

There are various tips what one can follow in order to become Preppy which tips cheap nfl jerseys,

are provided below: One appearance is the key to act as Preppy. D?tsk? Wear designer and branded clothes like Polo Shirts, Cable Sweaters, Sperry Top-Sider Shoes, Keds Shoes, Oxford Shirts because mannequin inside store.