So “Dragonstone,” this season’s first episode of HBO’s enormously popular series Game of Thrones, was a welcome relief from too many months without our beloved characters. I enjoyed it, as I always do. Good times.

There’s one part, though, that was a bit of a shit show.

And no, I don’t mean Sam’s montage or Ed Sheeran’s cameo.

(I’m kidding, Ed! Your Hobbit theme remails one of the best things about those films.)

SPOILERS Ahead.

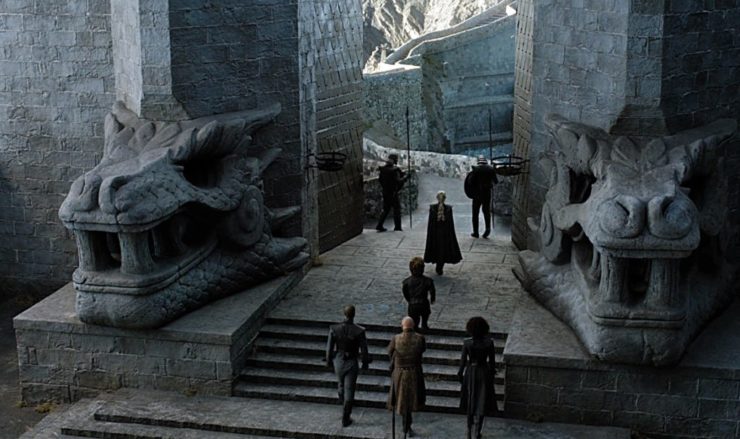

It was the part at the end of the episode: Dany’s arrival at Dragonstone.

Shall we begin?

Let me first say: this was cool. We’d been waiting for this moment since the show started. Dany’s been waiting almost her entire life. The visuals were stunning. The build-up, I thought, was perfectly on point. I applaud the amazing writers and directors for letting the moment unfold so deliberately. Spending such a long time on long shots without dialogue is rare in any entertainment these days, but it was perfect for the moment. Well done.

Only….

Where the hell is everyone?

Yes, I know Stannis “Burn the Babies” Baratheon left Dragonstone and took off to the north with his army (to get his ass kicked). But are you telling me he left nobody behind? Not even a token force in arms? And even if he didn’t do that—I’m putting on my historian hat now—there should still be people there.

(In the book chronology, of course, people most definitely are there: Stannis left Rolland Storm behind as castellan, and Ser Loras Tyrell subsequently destroyed him and seized the islands for the Iron Throne. This is because George R.R. Martin knows his history and is The Man.)

Look: Dragonstone is an important place in Martin’s world. Politically, culturally, strategically, if you want to rule Westeros you’d be well-served to hold Dragonstone. And it is, as we know, a truly massive fortification on a rock in the middle of the open sea. Both its size and its location present tremendous difficulties to anyone who might want to hold it, much less anyone who might want to seize it.

And that’s precisely why it’s so nonsensical that Dany finds Dragonstone deserted in the television show.

It might seem an odd analogy, but think about Dragonstone as a modern-day aircraft carrier. (Yes, I know that the island can’t move, but bear with me.) If you’ve ever toured an aircraft carrier, even a relatively small one—like the WW2-era USS Yorktown here in my beloved Charleston—you know that they must function as cities unto themselves. They can hold a lot of combat personnel, but they must also hold an enormous number of non-combat personnel to support all those folks: doctors and dentists, cooks and cleaners, mechanics and many more.

Take all that and multiply it a few times over and you might get something like the non-combat army that’s needed to support an army like the one Stannis had on Dragonstone. We’re talking thousands of laborers and tradesmen and people of every stripe.

Yet when Dany arrives they’re … gone? All of them? She sees not a single soul on the island. The gates at the shoreline are unlocked. The gates of the palace itself are unlocked. The doors all the way through to Stannis Baratheon’s super-secret war-council room are unlocked.

As a historian, I nearly choked.

Not only did Stannis not leave anyone behind … he didn’t even bother to bolt the doors?

Even aside from the fact that he was a glowering child-burner, I figure the dude deserved to die just for that.

Historically speaking, a good military leader doesn’t leave good military positions open for just anyone to waltz in and take them. As I said, I know Stannis was “all-in” to go help in the north. I get that. But this is still nonsense to leave it unoccupied.

Think about it like this:

If he lost and escaped the north, Stannis would need a place to retreat. Since few places are more defensible than Dragonstone, he should have left a small force there.

If he won and came down from the north, Stannis would not want to give his enemies places to hold him off. Since few places are more difficult to attack than Dragonstone, he should have left a small force there to prevent enemies from moving in.

I mean, sure, Stannis is a religious zealot and so maybe he thought that when the Lord of Light said “Go North, young man” His Flameness meant literally everyone including the beggars and so he got every friggin soul off the island and figured, well, ol’ Fires Himself will protect the place so I don’t need to bother locking a door or anything and yeah sure that’s stupid but Stannis is, as I said, a fundamentalist zealot …

Okay, maybe…but then not one person decided to move in after he left? Like not even some poor fisherman from Rook’s Rest who looked out across the water as they all sailed away and thought to himself, “Hey, you know what beats living in this leaking straw-roofed freaking mud-hovel? Living in there.”

I can buy a lot of nonsense in my fantasy, my friends, but this I cannot abide.

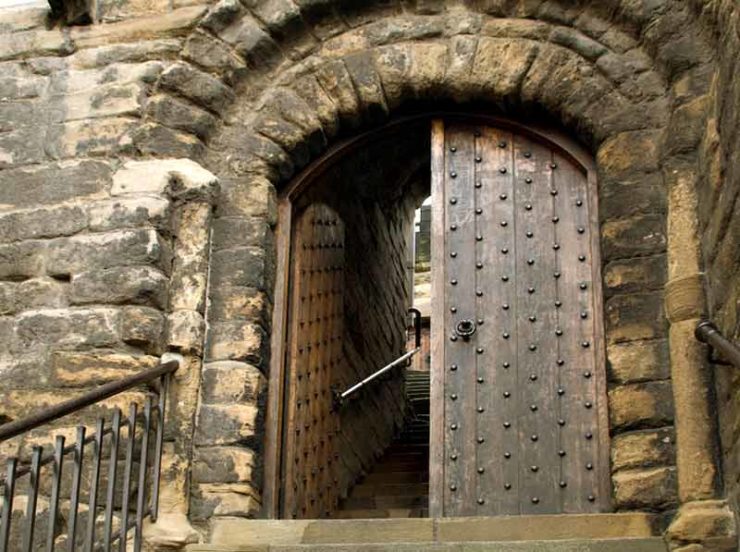

Speaking of Dragonstone, I saw some discussion online about people thinking it’s strange that the fortification’s gates opened inward instead of outward—they thought that inward-opening gates would be easier to knock down with battering rams than outward-opening ones would be, and thus HBO’s inward-opening ones weren’t “realistic.”

Interestingly, this is a detail that the Game of Thrones gang nailed. Medieval gates opened inwards, and for a number of good reasons.

1. Humans can push things better than we can pull them. It’s easier to push a gate shut than to pull it shut. This is especially true under attack. If you’re pushing the gate shut, the gate is protecting you; if you’re pulling it shut, you’re totally exposed.

2. If someone is trying to open the gates, having them open inward allows you the option to barricade the gate. Outward-opening gates have no such option.

3. If a gate opens outward, then its hinges would be on the outside, which is … um, sub-optimal for defense to say the least.

Anyhow, here’s hoping HBO hits more of these realistic medieval notes in future episodes of this “medieval” fantasy… and fewer empty-headed empty castles.

(H/T to Jack Cranshaw, who suggested on Facebook that I discuss medieval Dragonstone matters. Hey, why aren’t you following me on Facebook? Or on Twitter?)

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven and its sequel The Gates of Hell, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Literature at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy series set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven and its sequel The Gates of Hell, is available from Tor Books.