This was going to be post on Troy and SFF. But then I realised: I haven’t actually read David Gemmell’s Trojan series, nor Jo Graham’s Black Ships, nor, indeed, can I actually remember reading a SFF novel which dealt with matters Trojan. (I’m far from as widely read as I ought to be.) It might amuse me to discuss Ilium’s windy plain solely in terms of the 2004 film Troy (which, disappointingly, left out all the gods) or that old Xena episode, “Beware Greeks Bearing Gifts,” but since I’m not sure how amusing anyone else would find it, I’m going to cast my net a little wider.

The Iliad can arguably be described as the oldest epic fantasy in the European canon. Despite being epic in length, it deals with a reasonably short amount of time, mere weeks, opening as it does with Apollo’s plague upon the Achaeans and Achilles’s resentful flounce back to his tent (a fit of sulks brought on by the dishonour of being deprived of his rightful battle-prize, the woman Briseis), and closing with the funeral rites of Hector. The intervening stanzas are filled with interfering gods and the combats of god-like mortals. Not to mention a whole bunch of standing around and talking: anyone who ever complained of the lengthy speechifying in Tolkien’s council scenes will hardly love the jawing that goes on in and around Troy and Mount Olympus during The Iliad.

For all that, The Iliad doesn’t even encompass the other famous incidents of the Trojan war. The death of Penthesilea. The death of Achilles himself. The suicide of Telamonian Ajax.* The famous hollow horse devised by Odysseus and the Sack of Troy. These are iconic moments—I think so, anyway, even if the entire story is one bloody tragedy after another. Which, come to think of it, is probably why I can’t remember reading anything with obvious Trojan influences in SFF: I’m not sure High Tragedy is a mode that long-form speculative fiction is often much engaged with. “Everybody dies—horribly” isn’t everyone’s favourite conclusion, after all.

*So-called to distinguish him from Ajax the son of Oileus, AKA Aivas Vilates, “sordid Ajax,” best remembered for the rape of Cassandra.

The heroic Greek stories of the pre-Classical period combine this tragic violence—tragic, in that no one actually gets anything they desired**—with the heroic selfishness of a society made up of competing warrior groups allied in greater or lesser degrees by shared language and kinship ties. Only two things matter: glory, or personal reputation for success, by which the war-leaders such as those in The Iliad attract men to follow and support them; and plunder, the fruit of success, by which war-leaders cememted the loyalty of their following in a relationship of reciprocal support. The honour code of Homeric Greece is, by modern standards, rather amoral, and it’s difficult to see the heroes who follow it as justified or right.

**Except possibly Menelaus, which has to be a tragedy for Helen.

It’s a lot easier to find sympathy for the Greek protagonists of the Persian Wars. Herodotus’s account may well combine the greatest invasion story of all time with the greatest victory against the odds, and includes the most famous last stand in European history. (The Persian view of events doesn’t survive, but I imagine they found the hyperbole of the Greek account a little over the top.)

The last stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae*** (made to seem rather ineffably silly by the film adaptation of Frank Miller’s 300, or at least I found it so) has echoed through the years—not least, to my mind, in Faramir’s stand at Osgiliath and the Causeway Forts in the Lord of the Rings. Although Faramir and some of his men survived, so perhaps the comparison isn’t entirely apropos.

***One must wonder what the Persians under Xerxes thought, after winning such a victory. The battle of the Hot Gates certainly made Sparta’s reputation, although by the late fourth century, the reality was no longer living up to the mystique.

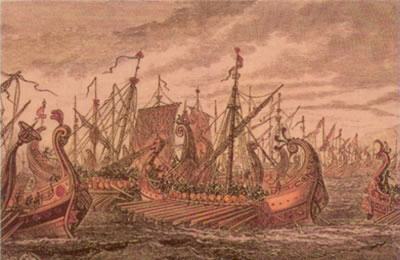

Thermopylae is the more famous battle. The more significant—the battle which put the Greeks on the road to Plataea and Persian abandonment of their forward policy on the mainland as decidedly not cost-effective—is the naval battle of Salamis. The general Themistocles convinced the Athenian assembly that a Delphic oracle which told them to put their trust in “wooden walls” referred to their naval forces, not the walls of the acropolis. Athens was evacuated of its citizens, and after some politicking, battle was joined.****

****It’s one of the few battles of the Greco-Roman world where a woman is recorded as one of the commanders: Artemisia of Caria, a client monarch of the Persians, who led five ships, and gave good (though ignored) advice.

Victory was famous, and nearly total.

I find myself surprised, writing this, how little direct influence from either Troy or the Persians Wars I can identify in SFF. It doesn’t seem right to me to simply pass over them, though—possibly because I’m entirely too fond of the Greeks—so I hope that the smart people hereabouts will have some thoughts in the comments.

Liz Bourke is reading for a research degree at Trinity College, Dublin. A longtime SFF fan, she also reviews for Ideomancer.com. She’s nowhere near as well-read as she’d like to be.