The second series of BBC’s super-popular Sherlock concluded its three-part offering over the weekend, and the results were shockingly unexpected and ridiculously exciting. This feat is impressive in it of itself, but seeing as the basic plot and concept are taken from the famous (or infamous) Conan Doyle-penned story “The Final Problem,” doubly so. It’s all been leading to this, so what happens when the 21st century versions of Sherlock and Jim Moriarty try to sort out their final problem? The answer is chock full of spoilers and twists, in what was one of the most fun and engaging Sherlocks yet.

Spoilers throughout. Really.

The episode opens much like the first episode of Series 1, “A Study in Pink,” with John Watson talking to his therapist. She wants to know why it’s been so long since John has come in for an appointment. Incredulous, John says, “You do read the papers, you know why I’m here.” And then he reveals what someone who reads the papers should know; Sherlock Holmes is dead.

After the title sequence, we’re told it’s three months earlier and Sherlock Holmes is a bigger media sensation than ever. After recovering a stolen painting called “The Falls of Reichenbach,” the papers have taken to calling Sherlock “the hero of Reichenbach.” This results in an amusing sequence in which Sherlock is given gift after gift from various thankful parties, only to have each one be unsuitable to his tastes. This culminates perfectly with Lestrade and the rest of the Scotland Yard force giving him a deerstalker cap as thanks for helping with another case. Much to his chagrin, and at the urging of John, Sherlock dons the cap for the cameras.

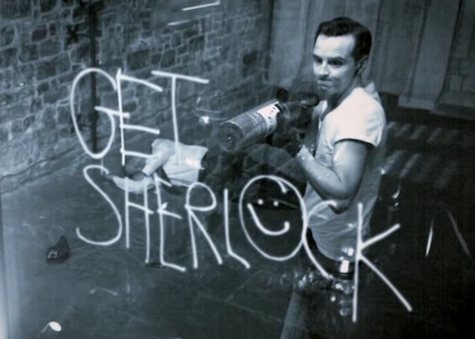

Later, back at Baker Street, John muses that the cap is no longer a “deerstalker” but rather a “Sherlock Holmes hat.” This serves nicely as a reference to the zeitgeist in real life about the famous Victorian detective, but also as an in-universe warning that the media surrounding Sherlock might be getting too big. Sherlock wonders aloud why John is concerned about this, and John worries the that “the press will turn, they always do ” Meanwhile, Jim Moriarty is free and walking the streets of London, specifically, the Tower of London. After donning headphones, Moriarty makes a few swipes on his smart phone. Simultaneously, with just the flick of a finger on an “app,” Moriarty is able to open the largest vault in the Bank of England, all the cell doors in the country’s largest prison, and walk in and steal the crown jewels. Before smashing the glass which houses them, Moriarty writes (in a fashion keeping with the Riddler) “Get Sherlock.” Shockingly, Moriarty is immediately caught and arrested.

At Moriarty’s s trail, Sherlock is brought in as an expert witness to help convict the master criminal. Moriarty is bizarrely offering no defense, despite having pleaded not-guilty. Sherlock mouths off and makes numerous observations about the jury and the court officials, which eventually gets him found in contempt of court. Prior to this, Sherlock has an altercation in the bathroom with a gossip reporter posing as a fan. He tells her off with the words “You repel me.”

Next, though the judge encourages a verdict of guilty, the jury inexplicably votes for Moriarty’s acquittal and he walks free. Though it makes little sense, it seems Sherlock was almost expecting this outcome. Moriarty soon comes round to Baker Street where he taunts Sherlock with his power. Manipulating the jury was easy for Moriarty: he had threatened all the families of each juror privately, forcing them into a verdict. The trial was nothing more than an elaborate advertisement for Moriarty, a way to show various criminal parties how powerful he really is. He tells Sherlock that they are living in a “fairy tale” and every fairy tale needs its villain.

Soon Sherlock and John are called in by Lestrade to assist with a kidnapping case. Previously, a package had been delivered to Baker Street filled with breadcrumbs, indicating Hansel and Gretel. At the scene of the kidnapping, Sherlock manages to obtain samples of boot prints, which he believes will help them locate the place where the kidnappers have taken the children. By putting various chemical elements together in the lab (with the assistance of Molly), he determines the kidnapped brother and sister are being held at an abandoned candy factory: an obvious reference to Morirarty’s bizarre fairy tale fetish.

The children are indeed there, and eating candy laced with mercury. However, when Sherlock goes to question the young girl, she screams at the sight of him. This precipitates a sequence of events where the other police officers working with Lestrade, specifically Anderson and Donovan, start to suggest that Sherlock himself may have been involved with the kidnapping. As Sherlock starts to suspect this plot to discredit him, he takes a cab, and inside is subjected to a deranged video from Moriarty outlining how he intends to make Sherlock look like a fraud and how everyone will turn on him.

Soon, Lestrade arrives at Baker Street and arrests Sherlock. Watson initially is not under arrest, but after punching Lestrade’s superior, the pair are handcuffed together. At this point, instead of going quietly, Sherlock and John make a break for it, complete with gun-wielding antics. They head for the flat of the gossip reporter Sherlock met before the trial, who has recently run an “exclusive” about Sherlock’s past for a local rag. Upon breaking into her apartment they discover she is harboring Moriarty, who claims to be a man by the name of Richard Brook. The journalist explains to John that Moriarty is a fictional creation, one of Holmes’s design. Richard Brook was the actor hired by Holmes to pretend to be his arch-nemesis. The evidence Moriarty has created to perpetrate this deception is deep, including Richard Brook’s job for a children’s program, one in which he tells fairy tales.

After leaving in disgrace and confusion, Sherlock oddly goes to see Molly and asks her for a favor that is never disclosed before his final confrontation with Moriarty. (In a previous scene, Molly was the only one who noticed that Sherlock was visibly worried, but acting strong around John.)

Throughout the episode Moriarty has lead Sherlock (and Mycroft and the government) to believe that he has a secret computer code, which allows him to open any door. However, upon meeting on the rooftop of St. Bart’s Hospital, Moriarty reveals there was never any secret code; he simply had a network of lackeys that he paid off. Moriarty’s trap and effort to destroy Sherlock is almost complete: the media has discredited the great detective as being a fraud, someone who hired actors and engineered the crimes he “solved.”

Now Moriarty is demanding Sherlock Holmes to commit suicide in disgrace. If he doesn’t, Moriarty has snipers ready to kill Lestrade, Mrs. Hudson and John. Sherlock realizes that he is safe from this fate as long as Moriarty is alive to call it off, but then, in a gruesome act, Moriarty shoots himself in the head. Sherlock calls Watson and tells him “the truth.” He claims he was a fraud, and that he is giving Watson his “note.” Sherlock then jumps and presumably falls to his death. Notably, just after Sherlock’s body hits the pavement, John is knocked over by a bicycle messenger, disorienting him at the scene of the tragedy.

Now Moriarty is demanding Sherlock Holmes to commit suicide in disgrace. If he doesn’t, Moriarty has snipers ready to kill Lestrade, Mrs. Hudson and John. Sherlock realizes that he is safe from this fate as long as Moriarty is alive to call it off, but then, in a gruesome act, Moriarty shoots himself in the head. Sherlock calls Watson and tells him “the truth.” He claims he was a fraud, and that he is giving Watson his “note.” Sherlock then jumps and presumably falls to his death. Notably, just after Sherlock’s body hits the pavement, John is knocked over by a bicycle messenger, disorienting him at the scene of the tragedy.

Time passes and we see John and Mrs. Hudson at Sherlock’s grave, where John gives perhaps the most heartfelt speech of the entire series and asks for one more miracle; the miracle that Sherlock is not dead. As Watson walks away from the graveyard in tears, the camera pans over to a figure standing in the shadows. Sherlock Holmes is alive!

Ryan’s Reaction:

Wow. This episode was not what I expected from a Holmes/Moriarty confrontation, and I couldn’t have been happier at my surprise. Whenever writers tackle and adaptation of “The Final Problem,” I believe they’re almost always poised to make it at least a bit more coherent than the original Conan Doyle story. The recent Guy Ritchie movie certainly accomplished this, by giving us perhaps the best justification for the Victorian Holmes to plunge into the abyss of the roaring Reichenbach falls. Here, in the contempary version of these adventures, the motivations of Moriarty aren’t as clear cut and aimed towards world domination. Instead, Moriarty wants to see Holmes completely broken and destroyed, even at the cost of his own life. This Moriarty is sadistic and cruel on levels unparrelled with other versions of the famous villain. The concept of driving Holmes to accept a lie of being a fraud, and also drive him to willing suicide are exceedling dark, and handled perfectly. The dialogue in almost every scene is spot-on, with special attention to the first scene in which Molly confronts Holmes about what’s really going on. It’s moving, and unexpected and acted wonderfully.

And then, the final scene with Sherlock and Moriarity in which Holmes says “You want me to shake hands with you in hell, I shall not disappoint you,” ought to rank up there with some of the best delivered dialogue of all time. The writing and the acting are top-notch in this one and I have to say, I didn’t see this plot concept coming at all.

The idea that Moriarty is out to discredit Holmes is totally brilliant, and the idea of Holmes “inventing” Moriarty exists in all sorts of pastiches, though most-famously in Nicholas Meyer’s novel The Seven Per-Cent Solution. Perhaps the other reason this notion works so well is because it addresses the meta-fictional conceit that Doyle invented Moriarty for the occasion of doing away with Holmes. Moriarty literally serves no function other than that, and is not character in the true sense of the word, at least not on the page in the original text. Now that Moriarty IS a fully-realized character, the writing of “The Fall of Reichenbach” acknowledges this quirk of the story, and layers on the meta-fiction with fairy tale stuff. Having Moriarty’s false identity even be a kindly-storyteller of children’s tales makes it even better and creepier.

I knew after I saw Sherlock’s bloodied body that he was not truly dead, but the final reveal of him standing alive was so satisfying. We know he must have had Molly do some medical mumbo-jumbo to him prior to his jump from the top of the building. Why else would he go to her? She was the only one of his “friends” who Moriarty did not mention. The idea that Sherlock alienates many people around him was played with in this episode as it served to fuel the media frenzy that he was actually a fraud. But on the personal level, it was nice to see that even those who he might mistreat, still care about him and will go great lengths to save him.

This was stunning end to a great second wave of what is probably the best version of Sherlock Holmes we’ve seen since the Jeremy Brett days.

Emily’s Reaction:

Okay, I have a thing for equal opposites, those stunning hero-villain duos. It’s like watching a perfect chemical reaction in lab class. So I’ve sort of been in love with this Holmes-Moriarty pairing from the get-go, and understandably concerned about their final outing. It had to do them justice, the both of them. Moriarty couldn’t be that phantom cardboard cutout that Doyle unfortunately created for “The Final Problem.” Holmes couldn’t go out with nothing more than an unseen brawl on a slippery outcropping. Give me the battle, the real battle, and make it frightening. I wanted to be dreading every second.

I was not disappointed.

To begin with, what they extracted from the material was honestly more impressive than any of the previous episodes. The whole idea of disgracing Sherlock, of making it about a descent in the eyes of the world, is basically taken from a simple piece of narration at the start of Doyle’s story: Watson explains that the reason he feels the need to put the tale to paper is because Moriarty’s brother wrote his own piece, lying about what truly happened, and Watson needs to set this to rights. It’s an honorable reason to be sure, but Watson wasn’t publishing this piece on the internet, where everyone can instantly tear it apart. So rather than write a rebuttal within the show, John Watson’s blog (if you don’t follow it during the series, I highly recommend it) merely contains a final insistence that Sherlock was his friend and wasn’t a fraud. And then he closes his blog for comments. Because this Watson doesn’t quite have the way with words that his canon counterpart did, and he simply can’t handle the backlash that this whole debacle has created.

What we get instead is his fretting throughout the episode, the fear in his eyes when he tells Sherlock that he doesn’t want anyone to think he’s a fake. Because this matters to John, but he’s not really a writer who can use words to spin Sherlock into the hero he sees. He’s just a guy with a cool blog who doesn’t have the power to defend his best friend. The fact that they pulled an entire emotional arc from one piece of setup at the start of “The Final Problem” is just gorgeous.

There’s also a way in which they flipped the story on its head completely: throughout “The Final Problem,” Holmes continually tells Watson that so long as Moriarty is brought to justice, he can count his career completed. This is ostensibly because he is aware that he might die, and could be trying to hint at Watson that he’s fine with his life ending here. (It’s also Doyle trying to tell the reader this, as he did intend it to be the final Holmes story when he initially wrote it.) But this Sherlock is too young, too manic, too intent on the next best thing to be done with now. He hasn’t been a career consulting detective successfully for long enough to be satisfied.

Instead, we have Jim. Jim who, it could be argued, set this whole thing up to answer a simple question: are you my equal? Really and truly? He tests Sherlock at every turn to find out, and by the end he’s disappointed. He thinks that Sherlock doesn’t get it, can’t get one over on him, that’s he’s just as boring as everyone else. After all, he fell for the “couple lines of computer code that can control the world” trick. (I have to admit, I rolled my eyes when they first mentioned that as Moriarty’s big secret. It was, as they like to say, “boring.” When it turned out that Sherlock was wrong to buy it, I was completely delighted.) But finally Sherlock reveals himself to be everything that Jim hoped he was. They are the same. He found his match, the only one in the whole world; you can only wonder how long he had been searching for that. And it turns out that Jim Moriarty is the one who is fine with his life ending, so long as he has that knowledge.

Provided that the world can’t have Sherlock either, now that he’s done.

But, just like their little game always illustrates, what he really should have asked again before turning a loaded gun on himself was, “What did I miss?” It was simple, of course. He had snipers trained on John, Mrs. Hudson, and Lestrade. He had all of Sherlock’s friends. Except the one who didn’t count.

Molly Hooper. She is undoubtedly my favorite addition that this show has made to the Holmesian universe. Earlier in the episode we were given a moment, that perfect moment where Sherlock was forced to admit that Molly was his friend too, for all that he couldn’t stand her awkwardness and bad attempts at flirting. And now that she was honest with him, he was finally able to be honest in return. But Jim didn’t know that. Moriarty missed one of Sherlock’s friends because he, like Sherlock previously, had overlooked her importance entirely. And we all know that’s where he made his mistake because only one person was available to help Sherlock stage a fake suicide.

The only question left now is, how the hell did he manage it? Who knows how long we’ll have to wait to find out. That’s just not fair. (And because it is TV, and only other question is, is Jim really dead? I will always be worried that he’ll suddenly reappear a few seasons later. Television can never resist resurrection.)

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is the Editorial Assistant for Tor.com. She had a disturbing nightmare after she watched this episode, where Jim Moriarty merged with some Guillermo del Toro-like villain. It was just as horrific as it sounds.

As Watson comes around the corner we see a lorry pulling away past Holmes’ body. On the back of the lorry is some folded fabric. The remains of a deflated air bag like those used for stunt falls? This would explain his insistence on Watson staying in one specific spot.

Holmes falls onto the air bag, rolls off onto the pavement and adds some blood. We do need some jiggery pokery to explain Watson taking his pulse (vaso-constrictor?) but before Watson can check anything else, the body gets wheeled away.

A fantastic episode, no matter how the death was faked.

@ian Wood – Agreed! It also makes sense of why Sherlock demands that John keeps his eyes on him right before he jumps – don’t want him seeing that setup occuring below. As for the pulse, if it’s not a weird body swap happening, my vote goes for the rhododenron. He mentions it being in the area where they find the kindapped kids, and it can be used to make someone appear dead to a medical professional. In fact, they used it in the first Ritchie Holmes film. ;)

“Holmes solves this mystery in 1 clue.” That clue being the girl screaming at him. Obviously the girl recognises him. But they’ve never met. So Moriarty wore a Holmes mask. Holmes figures this out (of course) and gets Molly to agree to cover up any oddities with any corpse of Holmes. Holmes puts a Mission: Impossible mask on Moriarty’s body and hurls it over the edge. The bicyclist is an Irregular whose sole task is to knock down Watson. Watson, thus disoriented, is unable to penetrate the ruse. “Holmes” is then given a closed-casket funeral and that’s the end.

If you watch carefully, Holmes is falling perpindicular to the building, but lands parallel to the building. Something funky happened there.

Watson was likely fooled through the liberal use of the Baskerville hallucinagen (fear and stimulus) administered by the bicyclist. Holmes’ heart could have been racing and Watson would have felt nothing.

The problem I ultimately arrive at is how did Holmes fool people who weren’t Watson? There was a crowd of people there, whoever was driving the lorry (assuming that person wasn’t Molly), Watson’s sniper, and, presumably, at least two spotters that Moriarty had in place to call the hitmen when/if Holmes jumped/didn’t jump (placed near the corners of the building, two spotters would be able to see every side of the building).

Ultimately, I think the lorry was involved, and a corpse that looked passingly like Holmes (Watson on Baskerville wouldn’t notice the difference), but somehow the switch was made in mid-air (that’s the part I haven’t figured out yet).

Edit: @jdc The problem with that theory is that it depends on the camera lying to us. A living person definitely jumped, and fell, off the top of the building, according to what the camera showed us. There is one cut between Holmes falling and landing, and between that cut Holmes changes orientation from perpindicular to the building to horizontal. I believe something happened then, probably a body-swap with a non-Moriarty corpse double prepared by Molly.

@Azuaron: I need to look at the fall on iPlayer again. But I find the idea of somethign changing during the fall to be much harder to swallow than a corpse being shoved off.

Maybe the girl’s scream is le herring rouge.

OTOH, while I liked the revelation that Moriarty was lying about the “magic key” I was deeply unhappy that Holmes fell for it. But maybe “Sneakers” is his favourite flick. Cattle mutilations are up.

@jdc Holmes, at the top of the roof, within sight of Watson, takes the phone away from his ear, casually tosses it aside, leaps off the building, and flails on the way down. I’m going to be deeply dissatisfied if it ends up being, “All of that was somehow a lie, he pushed a corpse off.”

@Azuaron. Hmmm. Maybe Holmes learned advanced falling techniques while defenestrating US intelligence agents?

More seriously, does the program show anybody reacting to Holmes on the roof other than Watson? Before the jump/fall I mean. My memory says no but not sure.

It was not a corpse pushed off the building – we saw the arms flailing as Holmes jumped. And I think it was Holmes. The switch was done after the jump. Watson is knocked over by a bicyclist – that is surely significant.

Holmes was shown earlier playing with a squash ball – is this the “squash ball in the armpit to stop the pulse” trick? Watson finds no pulse on the “body”…

I thought it was wonderful – and Molly, throughout the two series, has become a character worthy of top billing alongside Holmes and Watson.

The final problem is how on earth anyone is going to accept the return, after what Moriarty did to Holmes’ reputation.

I think Mycroft has to have been involved in setting up the fake suicide. He has past form on faking death, after all. And Moriarty’s corpse is up there in the roof, damning evidence against Holmes.

I feel rather abused by all this.

Oh hai everyone. Apparently Moffat thinks we’ve all missed something.

Some of the theories for how Sherlock faked his death involve a lot of people working together. Molly, the van driver, the bicycalist, perhaps even the people in the small crowed that initially gathered around the corpse.

But Sherlock would know that a secret needs to be kept to as few people as possible for it to work. He chided Irene for this, when she faked her death. She believed Sherlock and John would keep her secret. But in telling them, she showed that she couldn’t keep her own secret.

***

Moffat now has both the Doctor and Sherlock faking their own deaths after destroying their own reputation.

The Doctor has already confided in enough people that his secret surely won’t keep. He had to confide in River to make it work. She shared the information with Amy and Rory, and that’s four people in on the secret. Five if you count Madge, who knows that he led his friends to believe him dead, although she doesn’t really know who he is.

We don’t know, yet, how Sherlock’s plan worked, so we don’t know how many people are in on the secret. But he’s less softhearted than the Doctor, and less likely to share the secret out of sentiment, as the Doctor finally did by going to see Amy and Rory at Christmas.

@11

It is funny that both Sherlock and the Doctor have faked their own deaths. But at least in Sherlock’s case, it’s in keeping with the literary source!

If it’s something “out of character” that Sherlock did, as Moffat says, maybe it has to do with his shaking hands with Moriarty? Does he ever shake hands when he’s being himself, not in disguise? I’m doubting myself now, but it’s not in keeping with his character to shake hands with someone he considers himself superior to -as he must to Moriarty, since he’s figured out how to beat him.

Thoughts? I can’t tell how this would be relevant, if it even is.

I just rewatched to see what I could see.

Just after the confrontation with Moriarty/Rich Brooks in the reporter’s flat Holmes says “The final step is…” Presumably he’s just worked out that Moriarty intends for him to appear to commit suicide and is laying plans from this point on. It’s just after this he visits Molly, and I think it’s a given that she was instrumental in covering up his survival.

That leaves us with two main theories that I can see. Either Holmes figured out a way to survive a fall from the roof or he figured out how to throw Moriarty’s body off the roof and make it look like it was him.

My problem is not that he couldn’t do either of these things but the camera angles seem to make it hard for him to actually have done either of them, we see him on the roof making the call, we see him mid fall, and we see him on the ground. Possibly the camera is lying to us but I’d be disappointed if that’s the case.

As far as Moffat’s thing that everyone has missed my guess would be that it’s Holmes asking for a moment to himself on the rooftop. He appears to be scanning the street below and spots something, possibly a convenient garbage truck? Not a theory I particularly like, seems inelegant, but it’s the best I have right now.

You know, right, that Jim Moriarty is not dead? The gun was not loaded, he had a squib on the back of his head for the blood, Sherlock never checked the body. Why would he, if he intended to go through with the suicide deception anyway?

When the police check that rooftop, they’ll find a bloodstain but no body. Guaranteed.

Also, if he was thinking (and Sherlock is always thinking) he recorded the entire conversation for future use.

Sherlock never checked the body.

Remember, Sherlock doesn’t need to look closely to notice every detail.

A casual glance, and observing the shooting, would be sufficent. He’d notice something like Moriarty falling in a deliberate way rather than just dropping pulled by gravity and pushed by the force of the bullet, or that the way the blood flowed from the wound didn’t match perfectly with the angle the gun was held at.

We may not be able to tell whether or not what we saw was faked (particularly since, IRL, it was faked for filming, they didn’t really kill off the actor.) But Sherlock will have noted details to know whether or not it was real in-story.

But Sherlock will have noted details to know whether or not it was real in-story.

Ah, such faith! Worthy of Molly, really. Touching….

I’m still betting myself a pint that Moriarty’s not on that rooftop next series (my favourite kind of bet, as I win either way).

I think perhaps the clue everyone missed is that Sherlock picked the meeting on the roof. Even someone with a normal mind wouldn’t want to give Moriarity an advantage, and putting yourself in a place where you can either be thrown off or forced to jump (remember, this isn’t the first time Moriarity has threatened either Sherlock or his friends to get Sherlock to do something, so it wouldn’t be that hard to figure out that was what he was intending). This means that Sherlock was intending to jump off the roof, and so had a plan to survive it. How he survived I do not know (probably something involving Molly, the lorry driver, and the biker, as other have said).

I think Mycroft is involved. He has past form on faking deaths. And keeping the fakery secret. And he knows what Moriarty is/was

But how can you restore Holmes’ reputation? How can he be the Great Detective again?

I have “I O U” stuck on my head. What does it mean? I am aware of the standard use of those letters but I can’t see a simple explanation for them in the context. Holmes’ owed Moriary a game? An explanation? A victory? Something does not add up, at least for me.

—

And, sidetracking, I will henceforth call this episode “Sherlock’s The Dark Knight Episode” from now on. Don’t get me wrong, I loved it. I just think that the interaction between Holmes’ and Moriary felt a lot like the interaction between Batman and Joker. It came even with a falling death, a conspiration to hide the truth and public rejection of the hero.

—

Further sidetracking: I believe that Moriarty, as written, is almost an excellent version of the Riddler. Is it too much fanwank of my part to wish for a Moffat/Gatiss written Batman vs. Riddler movie?

—

Back to the missing clue (assuming Moffat is not yanking our collective chain): I’ve read a lot of stuff from before he commented and practically all of the things mentioned were mentioned before. I believe it is something much more subtle, easily overlooked.

One thing I just realized, that I haven’t seen comments on, is that Sherlock got into the cab that Moriarty was driving without checking to see who the driver was.

After the events of “A Study in Pink” this seems rather reckless. You’d think that they’d have developed a habit of looking at the driver as they got in a cab, just to see who it is.

And even stranger, after seeing the bizzare video in the cab, Sherlock got out without first checking who had been driving. You’d think the video would have made him suspicious of the driver. And it would be easier to control the driver from inside the cab than from outside, as we saw when Moriarty just drove away when confronted.

The writers say that everyone is missing a vital clue, whatever that is. Molly has to be involved, and there is certainly another body involved. Rhododendron should explain about the pulse. All in all, a wonderful episode, in fact the best.

My vote is on Sherlock knowing that Moriarty would somehow force him to commit suicide, thus he created a controlled environment. He went to the rooftop, he told John where to stand for a specific viewpoint. For the other people around he could have used his Homeless Network for a kind of crowd control.

There was also a trick we learned in this week’s Mentalist where if you put a black squash ball under your arm it would appear like you have no pulse. We see Sherlock with a black ball before going up the rooftop ,which might also be a red herring.

I just hope we will get the new season soon, and a very good explanation.

@Ursula / #21: that’s a good point and I haven’t seen it mentioned before.

@Amarie / #23: yes, Sherlock was controlling how and where the final confrontation would take place.

To both: however, neither point explains how did he survive the fall (or how it was staged). That is the missing link.

I think we all agree on the general procedure: 1) Sherlock chose the roof, 2) Molly would help him get out of the morgue (and maybe with something else), 3) John needed to stand in a certain spot, 4) the illusion of death could be manufactured in any number of ways (and John was nervous enough to miss things).

I am starting to think that the “out of character” thing was the sacrifice itself. It may a cinic reading of Sherlock but I think he wouldn’t put himself in harm’s way just because.

I don’t think that Sherlock not noticing the cabbie was part of faking his death. It may, however be part of what led Jim to believe that Sherlock was ordinary and boring. After all, he used the same “no one notices a cabbie” trick on Sherlock twice, and the second time was in a situation where Sherlock already knew he was dealing with Moriarty.

I do think that when we find out how Sherlock faked his death, the answer will be simple, even elegant. It will involve Molly, but I don’t think it will involve anyone else being fully informed and involved. (E.g., the bicycalist may have been told “be at the corner at noon, at 12:08, ride into the fellow standing at the corner” but not that it was part of faking Sherlock’s death.)

There doesn’t seem to have been much time for an elaborate plan. And also, the more complex the plan, the more things can go wrong. And when more people are involved, there are more opportunities for Jim to bribe, blackmail and bamboozle people into messing it up.

1: He chose the location.

2: He knows everything, coz he is clever, so he predicted Jimbobs shooting.

3: Jim is also clever, so predicted that Sherlock would force him to do it

4:Sherlock didn’t check the body on purpose (becasue he knew he wasn’t actually dead.

5: Maybe just a bad location for filming but that bit of roof actually has a flat roof directly underneath it, not the road, but I think that it is just bad location/ filming etc.

6: Random thought, havent tied it in yet, but the dummy hanging in the office in the earlier episode probably has something to do with it (get that one in there just in case as a I told you so).

7: The waste truck on the road, all too much of a coincidence.

8: He knew Watson would be back once he found the housekeeper all well. (and so did the shooter?? already set up across theroad from the hospital)

9: I agree with the mask / screaming kid concept, could have had a corpse already (one of the russian assasins, littering the street from earlier in the episode) with a mask, chucked from the waste lorry that holmes landed in and drove off in.

Discuss :) either way – greast episode / series

Sherlock had already planned the fake suicide in order to resume his life as a Private ‘consulting’ Detective, having built up all the publicity (with Mycroft’s help) to draw Moriarty out.

@26 Armyandy

In point 5 you mention that flat bit of roof… it’s not bad filming, it’s was necessary to fake the suicide for Watson. That roof is not part of Sherlock’s building, it’s the next one over and the area he falls on is in between. The reason he tells Watson to move back to where he was isn’t to give Watson a clear view of Sherlock on the edge of the roof, it’s to give Watson an obstructed view of where he lands. You see the building twice… Watson gets out of the cab at 1:18:38 running time, and has walked around it by 1:18:47, Sherlock makes him go back and by 1:19:02 Watson is back around the building where he can no longer see the landing area.

My problem is that there must be more in on the conspiracy to work than just Molly. The landing area looks like private parking and therefore wouldn’t have a lot of public uncontrolled foot traffic. But without more viewing angles, we can’t just assume that everyone else that showed up also had obstructions in their way… some of them must have seen and therefore some of them must be in on it… unless we all think that no one else noticed the falling body until it fell out of the truck.

Sherlock has been threatened by Moriarty that he will ‘burn’ him to a crisp if he does not stop interfering at the end of series 1. Ignoring this threat, but knowing it to be very real, Sherlock continues to interfere, solving the theft of the Reichenbach Falls, the kidnap of the banker and the arrest of the wanted criminal. These lead to increasing press interest. This is the exact opposite of what Moriarty wanted Sherlock to do.

Mycroft is fully aware that Moriarty is genuinely a master criminal. As a major player in the British Secret Service he must be fully aware of the probable result of his divulging information to Moriarty about his brother.

Sherlock says that he is not prepared to play along with Moriarty’s game right near the start of the episode after the break-ins. Subsequently however he plays along willingly. He must suspect that the kidnap of the President’s children is Moriarty’s work. The girl, incidentally, may scream through being hypnotised or by auto-suggestion, rather mask wearing as suggested by many.

It is strange that Moriarty complies with Sherlock’s request to meet on the roof and doesn’t sign his text to say he is there with a kiss. Clearly Sherlock is keen to set the location of the final showdown. From what Moriarty says whilst having tea about a final fall he must sense that Moriarty would be compliant about a meeting on a roof.

It would seem that Sherlock is aware that having the code will not be sufficient to avoid suicide. Therefore he sets up a possible jump beforehand with help from Molly and possibly Mycroft.

Also out of character is that Sherlock names his three friends to Moriarty he is guessing who Moriarty has assumed are his only friends, Molly, Mycroft (not a friend as such) and Irene Adler are not named.

Sherlock says he is prepared to do things that ordinary people won’t do. This would include fooling his best friend that he is dead. And lying in order to make his suicide seem believable.

Why does he throw down his phone before he jumps? How does he know it is John in the taxi as he is dialling the number before he even gets out.?

The publicity surrounding his success makes it difficult for him to function as a consulting detective. Clearly Moriarty is part of a web of crime but maybe he is not actually at the centre of it. In the original stories there is an older Moriarty brother who is actually the power behind the throne. Once Sherlock is ‘dead’ and has disappeared it will be easier for him to work behind the scenes tackling this older brother’s network and also clearing his name as a fake. He isn’t a fake so there must be a reason why he would wish everyone to believe that he is one, recall his words to John asking him to tell anyone who will listen to him that he was a fake and that he invented Moriarty.

Everyone has been concentrating on HOW he cheated death, rather than WHY he cheated death.

Just some thoughts to ponder.

My late two cents:

That wasnt Moriarty on the roof, it was Richard Brook. Moriarty needs to stay out of the picture and wanted to test Sherlock. What is easier, training and actor or making a whole fake identity? This means that the truth that M is just the actor RB can be confirmed but since he is dead, it cant be confirmed that Sherlock did not hire him. Wrap a small lie in the truth was a theme of the episode.

Richard Brook is not as smart as Moriarty (but well trained). M would not have accepted the invitation to the rooftop but would have countered with another location. Sherlock knew this and as soon as he realized it really was Richard Brook, he knew he had to fake his death so he could be free to find Moriarty.

You will notice that when Sherlock points to a chair at the beginning of the Episode, actor Moriarty took the other one. Yet when Sherlock suggested a roof location, he didnt argue but just showed up?

I am really surprised that Watson fell for the whole confession thing from Sherlock. Sherlock even asked him why Watson cares so much what people think of him (Watson platonicly loves Sherlock, I do to) indicating that Sherlock didnt care. So when he went through the teary “confession”, it should have smelled bad to Watson.

My prediciton for Season 3:

Holmes searches for Moriarty and Watson figures out that Sherlock isnt dead. I also dont think Moffat will allow Sherlock to be publicly redeemed until the third episode. He was smeared pretty bad and dismissing it in one episode is weak and not Moffat’s style.

Take a look at the camera angles from when we first see Sherlock stand at the edge of the roof to the second time we presume that he is at the edge. The first time, the Capitol building is far behind his left shoulder, almost directly behind him. The second time, when he is on the phone with Watson, the same building is to the left of his profile. This would suggest that Sherlock is at a different location on the roof while speaking with Watson and someone else is at the roof’s edge and is sent over. Thoughts?

No one has mentioned the large newspaper article about the hospital.. you can see it in an earlier episode when SH is reading the paper – it’s on the front page. Something about the hospital getting a “refit”….