A group of five friends rent a cabin in the woods—the next day only four are alive. What happened and why is something the survivors are desperate to unravel.

Dawn came and they were still alive. All except for Marcie. Only at the end, they supposed she hadn’t really been Marcie anymore.

She was the only one who didn’t come to the cabin as part of a couple. Later on, the others—Chad and Annabelle, Mark and Donna—would all privately wonder if Marcie had been targeted the moment she walked through the door. If she’d been singled out for being single.

It seemed such an absurd notion, but after the night they spent at the cabin, their lives seemed to exist in a series of absurd notions, one following directly after another. The grief counsellors and psychiatrists told them this was a perfectly normal response to the trauma they had endured. That this was the way the human mind functioned when confronted with such terrifying and inexplicable events. The only way to move on was to accept the things that didn’t make any sense.

Which, to Chad and Annabelle and Mark and Donna, seemed like the most absurd notion of all.

Buy the Book

Shards

They drove up on a Friday afternoon after classes ended. They went in Chad’s new Expedition, an early graduation present from his parents. Annabelle sat next to him, playing navigator with Google Maps; Mark and Donna were in the back seat holding hands and staring at their smartphones; and Marcie was sprawled in the rear compartment with their luggage and groceries.

Chad glanced in the rear-view mirror and told her not to eat all their food before they reached the cabin, which earned him double fuck-you fingers from Marcie, who stood six one and weighed a solid two fifty, none of it fat. On the rugby field they called her the Steamroller.

The others ragged her about her size, but there was never any cruelty in their remarks. No more than the jibes they made about Chad’s thinning hair or Donna’s lazy eye. It was the way they’d always spoken to each other, ever since they were kids. The jokes and taunts that others used to hurt and humiliate, they turned into shields to protect themselves.

They’d learned early on that even though there was no perfection in the human body, there was plenty to be found in friendship. It was a strange friendship, to be sure. Their families and schoolmates didn’t understand it; they didn’t even understand it themselves. But they didn’t need to. It worked—they worked—and that was all that mattered.

Looking back, it made a strange kind of sense—an absurd kind of sense, one could say—that they should be the ones who ended up killing Marcie. They would have died for her if the situation had been reversed.

If you looked at it like that, killing Marcie was really the least they could do.

Still, there were some unanswered questions.

Like why did they dismember Marcie’s body after they killed her?

None of them had an answer for that. A fact that—strangely, absurdly—provided even more support for their collective story.

The grief counsellors and psychiatrists would later say the survivors mutilated their friend’s body because it was the only way they could externalize what they’d done to someone they’d known and loved since early childhood. Decapitating her and severing her limbs was their way of negating that relationship, of turning Marcie into a stranger, which, in a way, is what she had become to them during the course of the event.

The mutilation may have been vicious and violent, but it was also—strangely, absurdly—healthy.

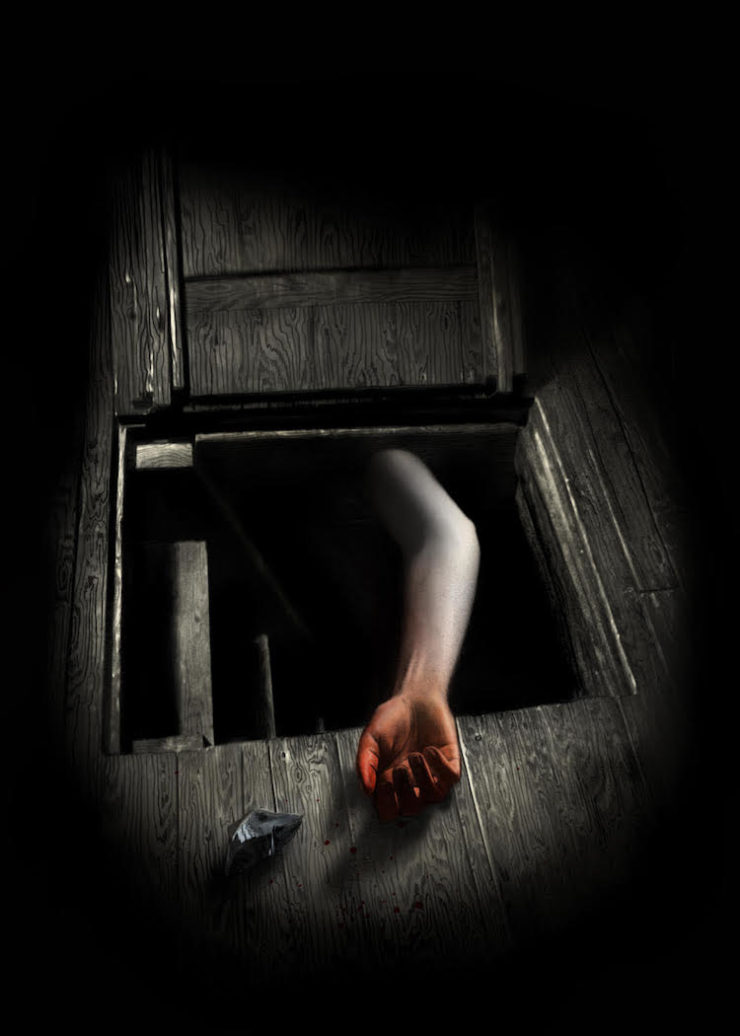

It was Marcie who found the trap door. She tripped over the ringbolt while they were bringing their stuff into the cabin.

“The fuck?” she shouted, stumbling forward a few steps and almost dropping the two bags of groceries she was carrying.

“What’s the matter, Marce?” Annabelle said, dragging her suitcase through the doorway on its small plastic wheels.

“Damn thing almost killed me.” Marcie went over and nudged the ringbolt with the toe of her shoe. “They should’ve covered it with a rug or something.”

“They who?” Chad said, stepping around Annabelle with a large cooler. Mark and Donna came in behind him, still holding hands, still on their phones.

“Whoever you rented this piece-of-shit cabin from.”

“Hey,” Chad said. “It’s got four walls and a roof. What else do we need?”

Marcie glared distrustfully at the trap door. “What the hell do you think is down there?”

Donna shrugged. “Probably the ghost of a demonic entity that will slaughter us all while we sleep.”

She was wrong, but not entirely.

After they unpacked their bags and put away the groceries, they made a fire in the stone-lined pit out back and roasted hot dogs and marshmallows. They washed them down with beer, then moved on to vodka. They finished the bottle—the first bottle—and Mark stuck it between his legs and chased the girls around the yard, thrusting his hips and crying out, Hoo-ah! Hoo-ah!

Marcie grabbed the bottle and looked at it skeptically. “We’ve all seen your dick, Mark, and this is way too generous. Maybe we could find you one of those little wee bottles you get on airplanes.”

Mark dropped to his knees, head slumped. “Why you gotta wound me with the truth like that?”

Donna hugged him. “It’s okay, babe. It’s not the size that matters, it’s what you do with it.”

Mark perked up. “I gotta pee.”

Donna backed away. “You can do that on your own.”

Mark rose shakily to his feet. “I’m not sure I can.”

The others watched him stumble off to the edge of the woods. Annabelle intoned in a narrator voice: “The police found his body the following morning. They thought his penis was missing, but it turned out they just had to look really, really hard to see it.”

They all laughed while Mark peed against an oak tree. He let go of himself to flick double fuck-you fingers over his shoulders, then cursed and brought his hands back around.

“Don’t get any on ya!” Chad called, and they all laughed again.

“Too late!” Mark called back. After he was finished he shuffled back to the circle, buttoning his jeans. “What’s the matter, Chad, you couldn’t spring for a place with an outhouse?”

“The cabin has a bathroom, numbnuts. You’re the one who decided to piss in the woods.”

“That’s part of the cabin experience,” Mark said solemnly.

“I’ll be sure to tell that to the owners,” Chad said.

“Who are the owners?” Marcie asked him.

“I don’t know,” Chad said. “I found it on Airbnb. Which reminds me . . .” He gave them his smooth lazy grin, the one that always preceded a bad joke. “After I graduate, I’ve already got an idea for my first entrepreneurial venture. It’s similar to Airbnb, only mine will be aimed at the Spring Break crowd. You know: beach, booze, and babes. I’m gonna call it AirTnA.”

The others groaned in unison. Annabelle threw a marshmallow at him. “Pig,” she said, but she was smiling.

“Seriously,” Marcie said. She gestured at the cabin with the hot dog skewered on her stick. “Who owns this dump?”

“How the hell should I know?” Chad said. “I checked the listings for a cabin in the woods, someplace within driving distance of the city, and this one looked good.”

“And by ‘good’ you mean ‘bad,’” Annabelle said.

“Didn’t you talk to someone?” Marcie asked.

“No,” Chad said. “I emailed. They quoted a price, I paid it, and here we are. What’s the big deal?”

An awkward silence descended, threatening the pleasant mood of the evening. Since Marcie was the cause of this particular bring-down, she knew it was her responsibility to provide the requisite counterweight to bring it up again.

“Whatever they charged,” she said, “it was too much. Just like your mom.”

They all looked at her for a short beat, then burst out laughing.

Tragedy averted, Marcie thought.

And it was.

For the moment.

They went inside when the temperature began to drop.

Chad started another fire, this one in the big fieldstone hearth, while Annabelle made a round of drinks. Donna was checking her phone and marvelling at the excellent coverage they got way out here in the sticks. Mark was still outside, putting out the old fire and gathering up their trash.

Marcie was in the main room, staring at the trap door.

“If you’re just going to stand there,” Chad said, kneeling in front of the fire, “could you at least be useful and hand me some more kindling?” He pointed at the pile of cut wood next to the rack of fireplace tools.

Marcie picked up a piece and handed it to him without taking her eyes off the trap door.

She couldn’t stop looking at it. When she was outside, sitting with the others around the fire, she hadn’t been able to stop thinking about it. It was like when she tripped over the ringbolt something had dislodged in her brain, and now it was rattling around in there like the only penny in a piggy bank.

What was down there? she wondered. Anything was the answer. Including nothing.

But she didn’t believe there was nothing. No, there was definitely something down there. She didn’t know how she knew that, but she did. Something . . . or someone?

No. There was no one down there. She was sure of that, not because of any particular reason but rather a feeling that was telling her—insisting to her—that there was something down there. Something other than dust and dirt.

But what?

She didn’t know, and while a part of her was okay with not knowing, a bigger part was not okay, because the not-knowing side was motivated by fear. She was afraid of opening the trap door and going into the cellar. She was afraid of what she might find. And she couldn’t accept that.

She took a deep breath, then blew it out. She needed to keep herself together. Her coach said fear was the forerunner of failure. Pretty words, Marcie thought, but they didn’t mean squat on the rugby field. She was the Steamroller, for god’s sake. Was she really going to be stopped in her tracks by a trap door that didn’t even look strong enough to take her full weight standing on top of it?

“Fuck no,” she muttered.

“Fuck what?” Chad said, jabbing at the burning kindling with a brass poker.

When he didn’t get a reply, he looked over his shoulder.

Marcie was gone and the trap door was open.

Annabelle was handing out drinks. When she was done she had an extra one. “Where’s Marce?” she asked.

Chad jerked his thumb at the trap door. “Down in the cellar.”

Donna snickered. “We’ll probably never see her again.”

“You’re one cold bitch,” Chad said.

“The coldest,” Donna said, her eyes glued to her phone.

Annabelle carried her drink (gin and tonic) and Marcie’s (rum and coke) over to the opening in the floor and peered inside. She couldn’t see anything beyond the first few steps of the wooden stairs descending into darkness below.

“Marcie!” she called down. “What are you doing?”

There was no reply.

Annabelle crouched, balancing the drinks on her knees, and tilted her head at a listening angle.

She couldn’t hear a thing from the cellar, which seemed strange to her. If Marcie was down there, she should’ve been able to hear her moving around. Marcie was a lot of things, Annabelle thought, but light on her feet wasn’t one of them.

“Come on, Marce.” Her mouth had gone dry and she swallowed with an audible click. “If you’re joking around, it isn’t funny.”

Mark came in the back door carrying a half-full garbage bag. “Shut the trap door and lock her in there,” he said. “Now that would be funny.”

Annabelle frowned at him, then turned back to the square-shaped hole in the floor. Locking Marcie in the cellar wouldn’t be funny, but it would teach her a lesson. Teach her not to scare her friends like this.

Annabelle stood up and was actually extending her foot to push the door closed when she heard something from below.

It was a low scratching sound, almost like radio static, but gone so quickly she wasn’t sure if she’d only imagined it.

She crouched back down and leaned forward, keeping the glasses in her hands upright so they wouldn’t spill. She tilted her head to the side again, like a satellite dish trying to pick up a stray signal.

She reached the tipping point and was trembling on the balls of her feet when Marcie’s face appeared out of the darkness and said, “Boo!”

Annabelle squealed and fell over backwards. The glasses flew out of her hands and spilled their contents across the plank floor. The others turned in unison, their startled faces turning to puzzlement as they watched Marcie climb out of the cellar.

She was carrying a record player.

It was a very old device—a gramophone, according to Donna, the music major—with a hand-crank on the side and a big brass horn that looked like a metallic flower in full bloom. Instead of a needle at the end of the tone arm, there was a curved hook of smoky black glass.

Marcie put it on the coffee table and they all gathered around it.

“It was just sitting there on the dirt floor,” she said.

“Sweet,” Donna said. “We need some tunes.”

Annabelle reached for the hook at the end of the tone arm.

“Careful,” Marcie said. “It’s sharp.” She showed a cut on the pad of her index finger, still weeping a bit of blood.

There was a record on the turntable, a plain black disc with no label.

“What do you think it is?” Chad wondered.

“Nicki Minaj?” Donna said.

The others laughed, then a deep silence fell over the room as they examined the gramophone.

Donna ran her hands along its smooth wooden sides.

Chad tipped his head toward the brass horn.

Marcie put her finger on the record and rotated it slowly around.

Annabelle reached out for the hand-crank.

Something might have happened in that moment, but the silence was broken by the plastic rustling sound of Mark digging around in the garbage bag. Snapped out of their collective trance, the others turned to face him.

Mark was holding the empty vodka bottle. He grinned mischievously as he waggled it back and forth in his hand.

“Wanna play a game?”

They lost interest in the gramophone after that. All except for Marcie.

She was still kneeling on the floor in front of it, spinning the record around and around.

The others were on the far side of the room, sitting in a circle around the bottle.

Annabelle said she didn’t want to play. Chad told her not to be a prude, and she accused him of only wanting to play so he could kiss Donna. Chad said his real plan was to see her and Donna kiss. Donna said she wanted to see Chad and Mark kiss. Annabelle shook her head and proclaimed them all childish. Donna said they’d be graduating soon and this would be their last chance to be childish, so they should enjoy it. Annabelle said fine, as long they didn’t enjoy it too much, and shot a pointed look at Chad.

Mark put his hand on the bottle. “I’ll start.”

He gave it a spin.

Across the room, Marcie turned the hand-crank on the gramophone.

The record began to spin, too.

When the turntable was going at a good, steady speed, Marcie lifted the tone arm and placed the needle on the spinning record.

No, she thought. Not the needle. The Shard.

She wondered where that thought had come from, but only for a second, then she inclined her head toward the brass horn.

There was nothing at first except the hollow sound of dead air and the low, expectant scratch of the needle.

The Shard.

Marcie leaned closer, wondering if it no longer worked, if a record could die like an old battery.

She heard only faint scratching, and was about to pull her head back when she realized the scratching wasn’t random: it had a pattern to it. It wasn’t scratching at all. It was a voice, a very low voice, and it was speaking to her, whispering to her. Asking her a question.

Wanna play a game?

A blast of sound exploded from the gramophone. A fusillade of horns so loud it knocked Marcie onto her back.

The squall rose to an ear-splitting level, then tripped back down the scale in a stuttering staccato that made everyone in the room feel as if icy fingers were tickling along their spines.

Their heads were all turned toward Marcie and the sounds coming from the gramophone—oblivious to the bottle in the center of their circle that continued to spin and spin.

As the horns trickled away, a tapping sound came in to take their place, a light pitter-patter as if of approaching footsteps. The tapping got progressively louder until it became the sharp rat-a-tat-tat of a snare drum, a percussive beat that sounded like gunfire.

The space between the drumbeats was soon filled by the razor-squeal of violins. A pained sound, as if the instruments were being tortured rather than played.

The auditory onslaught continued with a deep, pummelling bass that felt like a series of hammer blows against their eardrums.

Marcie suddenly jerked upright like a puppet whose master has pulled too hard on its strings. The music pounded out of the gramophone, causing the entire cabin to shake. The windows rattled in their frames. The floor was vibrating so much it looked like Marcie was hovering six inches above it. Later on they would all agree she didn’t turn to face them. She spun around. Like a record.

They knew right away something was wrong with her. Her eyes were glazed, her mouth hung slack, and her head was slumped at an unnatural angle. The autopsy would later determine her neck had been broken by that first burst of sound. She should’ve been dead, and yet she wasn’t.

As the others watched, Marcie reached out with one marionette arm and snapped off the gramophone’s tone arm. The record continued spinning on the turntable, and although there was no needle—no Shard—to play it, the sounds kept blasting out.

Sounds that became the soundtrack for everything that followed.

Donna was sitting on the front porch when the police arrived.

Who called them? she wondered.

Even though her arms were wrapped tightly around herself, she couldn’t stop trembling. She thought that being outside to catch the first light of day would help to drive away the icy aura surrounding her. It didn’t.

The first officers on the scene pointed their guns at her and told her to drop it. She didn’t know what they were talking about, then realized she was still holding the fireplace poker. It was covered in blood. So was she.

She understood how it must have looked. Only some of the blood was hers. Most of it was Marcie’s. There was a chunk of flesh stuck to the end of the poker. That was Marcie’s, too. It had come from one of her massive shoulders. Hitting her with the poker had been like hitting the tough hide of some large animal. It hadn’t stopped her, not at first. Not until the others joined in to help her. Killing Marcie had been a group effort.

Donna thought about letting the cops shoot her. She could stand up, raise the poker high over her head, and make like she was going to charge them.

She didn’t do it. Not because she was unwilling but because she was so fucking cold she could barely move. Her hand felt like a frozen claw, and it took all her strength to open it and let the poker fall to the ground. The police told her to stand up and walk toward them with her hands raised. She ignored them. She was done. If they wanted to shoot her, they could shoot her.

They didn’t. More cops showed up, and some of them stayed with her, watching her warily with their guns still drawn, while the others went into the cabin. Chad, Mark, and Annabelle were in there. And Marcie. Marcie was all over the cabin.

An ambulance arrived and a pair of EMTs tried to get Donna off the porch. She was hurt, they said, nodding at the slash wounds on her arms. She refused to move, wasn’t even sure she could move. She was so cold it felt like her ass had frozen to the plank floor. One of the EMTs noticed she was shivering and put a blanket around her. It didn’t help.

The EMT told her it was shock and would wear off eventually.

They were wrong on both counts.

Detective Russo entered the cabin and almost stepped on a severed arm. It was a strong, muscular arm with a large hand lying palm-down on the floor. For a moment he thought the nails on the fingers had been painted with red polish. Then he realized it was blood.

There was more blood at the mangled joint where the arm was once attached to the shoulder. A few feet away was the shoulder, still attached to the torso. Over there was another arm. A leg. A head with blood-splattered hair pulled back in a ponytail. The room looked like a slaughterhouse. Russo’s gaze drifted over to a pile of smashed wood and a dented brass horn, what looked like the remains of an old record player. What the hell happened here?

Two young men were seated on a ratty couch being treated by EMTs. The one on the left had a vertical gash running from his temple to the edge of his thinning hair. The other had what appeared to be a stab wound to his lower left side. A uniform was in the kitchen talking to a young woman sitting on a stool. She appeared uninjured.

Russo headed over that way, stepping carefully to avoid the puddles of congealing blood. As he was passing an open trap door, the head of another uniform popped up, giving Russo a minor heart attack. He froze in mid-step, clutching the mantel for support.

The uniform winced. “Sorry, Detective.”

Russo closed his eyes. “What’ve you got?”

“Nothing down there.” He looked around the cabin floor. “Looks like all the action happened up here.”

The other uniform came over from the kitchen. Russo nodded at the open notebook in his hand.

“Tell me.”

They told their story to the police, and from there it went to the media, and then out into the world.

Four friends had murdered a fifth after a night of partying at a cabin in the woods. The murder was committed in self-defence, after their friend experienced a psychotic episode and attacked them. Some reports insinuated that drugs may have been a factor, but this was never confirmed. There was no mention of the mutilation of the body.

Russo didn’t like it. Not one bit.

When he questioned each of the survivors, they had spoken calmly and clearly, with no outward signs of lying or evasion. Their stories matched and their wounds were consistent with the makeshift knife they recovered from the scene. None of them had criminal records or a history of violence. All four were squeaky-clean college kids, due to graduate in a month. But there was something wrong about them.

“Wrong how?” asked the police chief.

Russo shook his head. “I can’t explain it.”

The chief spread his hands. “Try.”

Russo paced back and forth across the office, running his hand through his hair. “The dead girl’s body. Why did they chop it up?”

“You read the shrink’s report. They claimed it was the only way to stop her. It’s abnormal, but considering their state of mind at the time . . .”

“I know,” Russo snapped. “Their story makes sense, I get it. But it’s not the truth.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means I don’t like it.”

“You don’t have to like it,” the chief said. “But you have to close it.”

So that’s what he did.

The coroner’s inquest determined that none of the four survivors was criminally responsible for their friend’s death and no charges would be brought.

The case was closed.

But not for Russo.

Summer.

Donna couldn’t get warm. One of the hottest summers on record and she was freezing. On the news, they talked about climate change and record-breaking temperatures. Donna was glad to hear it—if they were talking about the weather that meant they no longer cared about what happened at the cabin—but it didn’t change the way she felt. She was still fucking cold.

All summer long she cranked the thermostat in the house, and her parents kept knocking it back down. They argued about it constantly. Donna’s parents tried to be patient, figuring it was her way of dealing with the stress and the trauma. They told themselves it would pass.

One day in August, they returned from work to find the house so stifling it felt like they’d walked into an oven. In addition to turning up the thermostat as high as it would go, Donna had a roaring fire going in the hearth. They found her sitting on the floor in front of the dancing flames, clothed in three layers of sweaters and her winter coat.

Her parents yelled at her—Donna couldn’t hear them at first with the earmuffs she was wearing—then sent her to her room, something they hadn’t done in ten years.

Donna was holding the brass poker she’d used to get the fire going, and for a moment she considered using it on her parents. The way she’d used the poker at the cabin on Marcie. The way she’d used it on the empty vodka bottle.

When Marcie was dead and the music stopped, the bottle had still been spinning on the floor. It showed no sign of stopping, and to Donna this was the final indignity of the evening, so she smashed it with the poker. Smashed it and smashed it until it stopped spinning.

That was when she started feeling cold. It was like a chill wind wrapped itself around her, enveloping her, sinking deep into her skin. It ran through her veins like ice water, turned her bones into frozen sticks. It numbed her very soul and filled her with a hopeless dread that she would never be warm again.

Donna decided not to use the poker on her parents. She went upstairs like the good girl she’d been all her life. She thought about calling Mark—that’s what she normally would’ve done—but she didn’t. They hadn’t spoken since the cabin. None of them had spoken to each other. It was strange. They’d always been so close; they’d always been there for each other. Now they were like strangers. She didn’t feel sad about it, which was even stranger. She felt nothing about it whatsoever.

She climbed into her bed, pulling up the duvet and the heavy quilt she’d brought down from the attic. The heat from the fire and the furnace hadn’t been enough. She was still cold. Her parents said it was all in her mind, but what difference did it make? Hot, cold—they were all signals sent from the body to the brain. How was this any different?

She decided her parents were the problem. She couldn’t get warm with them constantly stopping her.

So she waited a couple weeks, until they went away on a weekend trip. They’d been spending a lot of time out of the house since Donna returned from the cabin.

After they were gone, Donna turned up the thermostat and made a fire. Like before, it did nothing to stave off the cold she felt deep in her bones and all through her body.

She stayed up late, shivering in her layers of sweaters as she fed one piece of wood after another into the hungry flames. It made no difference—she was still freezing, so she decided to make another fire, this one in the basement. She emptied a can of turpentine onto a stack of old wooden chairs her father had been meaning to take to the dump. Then she tossed a lit match onto the pile and went back upstairs to start another fire in the living room. And another in the den. She locked the front and back doors and went up to the second floor. She lit more fires in her parents’ bedroom and the guest room.

She went back downstairs. Thick black smoke chugged out of the basement door. The living room and den were burning nicely; flaming particles whirled through the air like a swarm of fireflies.

Donna surveyed her handiwork and decided it would do. She retrieved the brass poker from the rack of fireplace tools and went upstairs. She climbed into bed and pulled up the covers, clutching the poker to her chest like a teddy bear.

She listened to the strident beeping of the smoke alarms and the rustle of flames as they grew louder and louder. A flickering light soon filled her doorway. She closed her eyes.

The fire slipped into her room, climbed up the door, and spread across the ceiling in a red-orange wave.

Even as the room was engulfed, even as the flames crawled across the carpet and leaped up the bedsheets, even as the fire surrounded her body and encased her in a burning cocoon, even as her hair burned and her skin melted, even as her eyes boiled and spilled down her cheeks, Donna trembled and shuddered and shivered.

Right up to the end, she was cold.

Fall.

Chad couldn’t stand the silence. He could feel it nibbling at his mind, eroding his sanity. He couldn’t believe how much of it there was in the world, with all the people, all the noise. But it was there, vast mountains of peace and small pockets of quiet, lying in wait, threatening to destroy him.

It didn’t make sense. At the cabin all he wanted was silence. When the music had come blasting out of the gramophone, his first impulse was to shut it off, to stop those sounds from entering his head even if it meant driving iron spikes into his ears. The music was more than unpleasant; it was toxic, polluted, a raping of his auditory canals.

While Chad had taken no pleasure in what they’d done to Marcie, there had been a beatific smile on his face when they finally stopped the music. In the lull of silence immediately afterward, he’d felt a euphoric sense of calm and relief.

It didn’t last.

He was fine when the police arrived. Better than fine, actually, because they bombarded him with questions—questions that began as thinly veiled accusations but quickly escalated into perplexed demands for the truth.

Chad didn’t mind. He welcomed their inquiries, welcomed the sound of their raised voices, the louder the better. The others were sullen and barely coherent, but he was a regular chatterbox. He talked so much one of the officers suggested he might want to remain silent until his lawyer showed up. Chad couldn’t do that; he was already growing suspicious of the silence. The only way to banish it was to fill it with sound.

So he talked to the police, to his parents, to the lawyer they got for him, to the press (even though the police and the lawyer advised him not to). He didn’t care. He talked to anyone willing to listen, anyone willing to talk back to him, and it pushed away the silence. For a while.

Even though the cabin was big news that summer, interest waned over time and attentions eventually turned to the next tragedy. Soon Chad didn’t have anyone to talk to—even his parents were tired of listening to him and responded only with single-word replies and grunts—and the silence returned.

It became a presence in his life, haunting him, infiltrating all the gaps of his existence that he couldn’t fill with sound.

Nights were the worst. Lying in bed, trying to sleep with the house gone quiet around him. Leaving his television on helped him fall asleep, but in the depths of slumber the silence would return, telling him there was no escape even in the dreamworld. He’d wake up gasping, sometimes screaming, and although the sounds were caused by fear and anguish, they were sweet relief to his ears, reassuring him, telling him he was okay, when he knew he wasn’t.

The people he could’ve talked to about this, the ones he should have talked to—his friends—he made no effort to contact. He couldn’t say exactly why he didn’t reach out to them, only that he knew on some level they wouldn’t be able to help him. Just like he knew he couldn’t help them.

He felt bad about not attending Donna’s service, but the silence there would have been too great. There was no funeral, only a spreading of her ashes on the lakeshore, which Chad found ironic since ashes were supposedly all that had been left of her. The fire in which Donna had committed suicide ended up consuming almost every house on the street. The news said it was a miracle she was the only fatality.

Chad needed a miracle of his own, but he didn’t think one was coming. No one wanted to talk to him anymore, and talking to himself only helped in a small, putting-off-the-inevitable sort of way. He figured it was only a matter of time before he ended up like Donna, taking his own life once the silence became too much to bear.

As the days grew shorter and the leaves changed colour, the silence took on a new aspect. Almost as if it were adapting itself to Chad’s efforts to eliminate it.

Now when he entered a room, even if it was occupied, the silence was there. If he was at work, or a party, or a mall filled with people, he would experience a sensation like the volume of the world was being turned down to nothing. Then, at the moment he was about to start screaming, the volume would go back up again.

He went to the doctor even though he knew it was pointless. This wasn’t a hearing impairment. It was a life impairment. A warning from the silence that it could get to him anywhere, at any time.

One day while he was out for a walk—and pondering the idea of buying a gun to blow his brains out—a car drove by with its stereo blaring. The windows were up so he couldn’t make out what song was playing, but it didn’t matter. The sound was what mattered. The music. It was like an oasis in a desert. A blast of sweet relief from all the crushing silence.

He wondered why he hadn’t thought of it before. Talking to people, talking to himself, even leaving the television on while he slept. They were all stopgap solutions. The silence couldn’t be sated by the mere babble of spoken words. It wanted something more mellifluous. It wanted the pitch and rhythm of music.

Chad ran home and went up to his room. He had a small stereo and a couple dozen CDs. He put on the loudest one he could find—Nirvana’s Nevermind—and cranked the volume as high as it would go.

He nodded his head to the opening guitar riff of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” followed by the rumble of drums that ushered in the full blast of Kurt Cobain’s power chords.

It was music, and it was loud, but he could tell right away it wasn’t the solution to his problem. Even though it held back the silence, he could still sense it in the gaps between the music and the lyrics—lurking, waiting, biding its time, waiting for the song to end. It wasn’t the miracle he needed.

The next day he went to a pawn shop and looked at a selection of record players. Many of them were old, although none were as ancient as the one Marcie had found in the cellar of the cabin. He bought one and brought it home. There were records at the pawn shop, but none that he wanted. Perry Como. Lesley Gore. The Beatles. No, no, and no.

He needed big sounds. Horns that could make your ears bleed. Drums that could pound your bones to dust. Music that could lift you off the ground and make your very soul tremble.

He thought of the record at the cabin, but it was gone, smashed to pieces.

He tried searching for it on the internet even though he had nothing to go on.

He searched and searched until he realized the answer couldn’t be found on a computer.

The song was out there, somewhere, and he had to find it.

Before the silence took him.

Winter.

Mark couldn’t sleep. He would drift, he would doze, but he could never enter the proper restful state that most people took for granted. It wasn’t due to shock or stress or guilt or any of the other one-word diagnoses the doctors proposed to explain his condition. It wasn’t that he didn’t feel tired; he did, immensely so. He was simply incapable of shutting off his waking mind. It was like he’d forgotten how to sleep.

He tried drinking, he tried drugs, he tried drinking and drugs. He tried tricking his body by going through the ceremony of his sleeping routine: brushing his teeth, putting on his pyjamas, climbing into bed, putting his head on the pillow. All in the hope of drawing the attention of the Sandman.

To no avail.

His parents wanted to send him to a sleep clinic, but Mark refused to talk to any more doctors. They couldn’t help the others—Donna dead, Chad missing, Annabelle crazy—and they wouldn’t be able to help him.

Eventually he grew to accept his sleepless state—mostly because he didn’t have a choice—and began to explore the new vista that had opened up before him.

Nighttime.

While everyone else was tucked into their beds, luxuriating in slumber, Mark walked the streets in his neighbourhood. He explored other people’s houses, sneaking in through unlocked doors and windows. He never stole anything or damaged anyone’s property. He simply strolled from room to room, checking things out, admiring the interior world of other people’s lives. He told himself he was only killing time, of which he had plenty these days. It never entered his mind that he was practicing for his future career.

On one of his late-night wanderings he ended up at the police station. He’d been there many times over the summer, usually during the day and in the company of his lawyer. It felt strange to be there now, alone at night. And yet, in another way, it felt perfectly right. As if he’d been drawn to this place.

He took to watching the police station. It was never closed, but late at night there were usually only a couple people working in the building, sometimes only a single desk officer manning the front counter.

Sneaking around to the back of the building, Mark broke a basement window and slithered inside. He landed on the concrete floor of an exercise room, with various pieces of workout equipment and a stack of gym mats against one wall.

He exited into a darkened hallway and wandered around until he found what he was looking for.

The evidence room.

The door was locked, but on the wall next to it there was a key on a hook below a handmade sign that said: return key when you are done with it. do not take it home with you!

“Fair enough,” Mark said.

He unlocked the door and went inside.

The evidence room was a long dark cave divided into narrow corridors by a series of free-standing metal shelves. Mark flicked a wall switch and fluorescent tubes sputtered to life overhead, filling the room with a cold, sterile light.

The shelves were lined with banker’s boxes, each one with a different case number written on it. Mark didn’t know their case number, so it took him a long time to find what he was looking for.

When he did, he sat on the floor with the box in front of him. It was like Christmas morning and he was about to open his present. Only he already knew what he was getting.

He opened the box and dug through a pile of evidence bags until he found the one with the gramophone’s tone arm in it. He took it out—the cylindrical tube with the hook of black glass on the end—and held it on the palm of his hand. It felt like nothing. It felt like everything.

He remembered the night at the cabin when Marcie snapped it off the gramophone. He’d thought she was going to attack them with it. That she would let out a primal scream and come flying through the air, slashing and stabbing. That’s what they told the police.

What really happened was that Marcie hovered in the air for a moment, clutching the tone arm in her fist, then she drew the obsidian hook across her own throat. As the skin parted and blood spilled out, the music grew louder and louder. It was unlike anything they’d ever heard before. It was the opening of something terrible, or something wonderful. They never found out which because they didn’t let it finish.

Mark wondered now if that had been a mistake. If instead of killing Marcie and destroying the—

The door opened.

Mark leaped to his feet.

He expected to see the outline of the desk officer framed in the doorway, but it was a different shape. A familiar shape.

“Chad?”

“Hello, Mark.”

Chad stepped into the room. His expression was calm, almost serene, as if he expected to find his friend here waiting for him. His gaze fell to the object Mark was clutching to his chest.

“I haven’t been able to sleep,” Mark blurted suddenly. “Not since the cabin. I thought if I found it . . .” He stared longingly at the tone arm. At the Shard.

“I have a song stuck in my head,” Chad said. “The song. I thought that”—he nodded at the Shard—“would help me find it.” He tilted his head to the side. “Maybe it’s a lullaby.”

Mark looked up hopefully. “It could help both of us?”

“Maybe,” Chad said. “But I think we have to help it first.”

“What do we need to do?”

“Things,” Chad said. “Awful, horrible things.”

Mark noticed his friend’s hands. There was blood on them. He thought of the desk officer.

“They’ll probably write books about us,” Chad said.

“What about songs? Will they write songs?”

Chad smiled. He reached out and put his hand around Mark’s, so they were holding the Shard together.

“I think they will.”

And what beautiful music they would make.

Spring.

Annabelle couldn’t stop spinning. Her thoughts were awhirl as the one-year anniversary of the cabin approached. Her attention span was in tatters; sleep was virtually impossible. Her mind kept going back to that night—not to Marcie and the music, but to the game of Spin the Bottle they’d been playing before the horror began.

She should have been thinking about the violence of that night, the loss of her friend and the miracle of their own survival, but what kept popping into her head was the idea, the conviction, that Chad only wanted to play the game so he could kiss Donna. He had denied it at the time, but of course that’s what she expected him to say.

In the weeks and months following the cabin, she became trapped in a circuit of denial and disbelief—thoughts of Chad and Donna kissing, touching, fucking, kept spinning around in her head like a torrid tornado—and there seemed to be nothing she could do to break herself out of it.

She stopped talking to them—which was easy to do, since the others stopped talking to her as well—but it didn’t stop the whirling dervish of her thoughts.

The only thing that provided the slightest bit of relief was staying in motion. Walking, jogging, running, sprinting—it didn’t matter as long as she wasn’t standing still. When she stopped moving, that’s when the thoughts returned, falling on her like a horde of vampire bats.

She went for long walks around town and in the woods behind her house. She went out at any hour, day or night, whenever the images in her head threatened to overwhelm her. Her parents grew more and more concerned, especially when a woman in town went missing. They tried to get Annabelle to limit her wanderings to the daylight hours, but she ignored them. She walked when she had to walk. This was the way it had to be. She knew there was no hope of clearing her mind; the best she could hope for was to quiet it.

And it worked.

For a while.

Over time the thoughts began to infiltrate her sleep, filling her dreams with images of Chad and Donna, their naked, sweaty bodies locked together, writhing on the gritty floor of the cabin, with the empty vodka bottle next to them, spinning, spinning, spinning.

On a cold morning in March, it all became too much to bear, and Annabelle was flung from her noxious nightmares like a circus performer shot from a cannon. She could actually feel her mind coming untethered, the guy wires of her sanity popping loose one by one.

She ran outside in only a T-shirt and a pair of pyjama bottoms, her bare feet punching holes in the fresh blanket of snow that had fallen the night before.

She ran and ran, but the images in her head remained. She couldn’t outrun them, couldn’t push them out of her head as she’d done before.

Crying out in fury and frustration, she picked up speed and ran headlong into a thick oak tree. She struck it hard, throwing her arms up at the last second to brace for the impact, and went stumbling into another tree. She bounced off it, her feet moving frantically to keep her from falling, and pinballed off a third.

She continued to twirl around, waiting for the inevitable moment when she’d hit something hard enough to knock her down. While this was happening, she became aware of something: those poisonous thoughts of Chad and Donna had vanished. They’d been knocked from her head just as her body had been knocked from one tree to another.

Finally she came to a stop, her breath pluming in misty gasps, her feet so cold they were numb. In the same instant, the relief she’d experienced began to evaporate and the thoughts slipped insidiously back into her mind.

She threw her hands at the gray sky and shouted, “What do you want? What do you want?”

She spun and screamed at the trees, her feet pounding the snow into the frozen ground . . . and the thoughts dissipated again. She slowed and felt them return.

It was the spinning, she realized. Not just moving but spinning! That’s what kept the thoughts away.

She started twirling around and around with her arms stretched out to either side. The thoughts melted, like the snow beneath her feet, like the tears spilling down her cheeks.

She kept spinning until she made herself sick. Stumbling against one of the trees, she gripped the rough bark in one hand while she bent over at the waist and vomited onto the pristine snow.

She’d never felt better.

From that moment on, everywhere she went, Annabelle was spinning. She was like a human top, twirling and pirouetting as she walked around the house or strolled down the street. Step, step, spin, step, step, spin. She didn’t have the grace of a ballerina, or the balance, and the dizziness that came with all the spinning contributed to a lot of falls and collisions. One time, on her way to the kitchen to make herself a sandwich, she walk-spun through the dining room and stumbled into the hutch containing her parents’ wedding china. She was barely able to get out of the way before it toppled over and landed facedown on the floor, plates and cups exploding with a rattling, ear-splitting crash.

Her mom and dad were pretty upset about that one, but their anger turned quickly to concern for her mental state. They told Annabelle, as calmly as they could, that it wasn’t normal for her to be spinning around everywhere she went.

Normal? Annabelle wanted to shout at them. I left normal a long time ago. I left it at the cabin.

That was when it first came to her, the thought of going back, although she supposed it had always been there, like the images of Chad and Donna that had taken root in her brain. Because the times she felt better—or as close to better as she got these days—were when she was outside, walking and spinning her way farther and farther from her house. At the time she’d thought it was only the relief of being away from her parents and their well-intentioned but mostly annoying concerns. Now she realized it wasn’t just the spinning that drove the images away, it was the fact she was moving as she spun, spiralling outward from the nexus of her life to some unknown destination.

Only it wasn’t unknown. She knew exactly where her spinning was trying to take her.

The cabin.

Going back was the last thing she wanted, but she knew there was no way she could keep spinning for the rest of her life. Unlike the empty vodka bottle, she would have to stop at some point, and when she did, all those horrible thoughts would be waiting for her. She wouldn’t live like that. She couldn’t.

So she went back.

She took her parents’ car, telling them she was going shopping. They were relieved she was doing something so normal, something the old Annabelle would’ve done. They told her to enjoy herself. She said she would. They told her to take her time and enjoy the day. She said she would.

Even though she remembered how to get there, Annabelle took a circuitous route, driving away from her house and through her neighbourhood in wider and wider circles until she left the orbit of town and entered the woods.

When she finally arrived at the cabin, she was surprised to see it looked the same. She’d heard it had become a site of morbid notoriety for true-crime buffs, and that one particular kill club had even recorded a podcast here shortly after the police released the crime scene. She was especially surprised to find it empty today of all days. The one-year anniversary. Maybe the cabin was keeping them away.

Annabelle got out of the car and walked up onto the wide front porch. The door was open. She went inside and looked around and around, spinning as had become her practice these days. She expected to see skeins of old police tape on the floor, or empty beer bottles from the kids drawn to this place with tales of murder and mutilation. But there was nothing. It looked exactly as it did the day she and her friends had come here.

She was walking and twirling across the floor when her foot struck something and she went stumbling toward the fireplace. She managed to grab onto the mantel, then turned to see what she had tripped on.

It was the ringbolt in the trap door.

She went over to it, performing a quick spin without even thinking about it, and knelt. She remembered Marcie coming up from the cellar with the gramophone. She remembered the music that wasn’t music, sounds that shouldn’t have existed when Marcie tore off the tone arm, but continued to pound out of the brass horn. She remembered the way it felt when those sounds poured into her ears and entered her mind.

She remembered killing Marcie, their poor sweet friend, and destroying the gramophone and the record. Only that didn’t put an end to the sounds. Because they weren’t really coming from the brass horn. They were coming from Marcie. So they fell on her and dismembered her, chopped her body to pieces because that was the only way to make it stop.

And she remembered what happened afterward: the others taking the Shard and marking themselves with it. Donna slashing her arms. Chad drawing a jagged line across the side of his face. Mark stabbing himself in the side.

When it was Annabelle’s turn, she stared at the Shard in her hand, the others watching her expectantly . . . and dropped it on the floor.

She couldn’t do it. She wouldn’t. She remembered the bottle, the one that wouldn’t stop spinning until Donna smashed it with the poker. She remembered telling them she didn’t want to play their game. She didn’t then and she didn’t now. She refused to mark herself.

Only it didn’t matter. She was still marked, and the music was still alive, still playing in their heads over and over and over again.

That’s what this was all about. That’s what had brought her back to the cabin.

It was the song, and it wanted what every song wanted: to be heard.

She pressed her finger into the dust on top of the trap door and drew a spiral curving outward and outward. Then she made a fist and knocked on the old, dry wood.

She went over to the couch and sat down.

She didn’t have to wait long.

Shortly after the sun went down, the trap door rose. Chad and Mark climbed out. They were filthy, their clothes smeared with dirt, their faces streaked with dried blood.

Annabelle was no more surprised to see them than they were to see her.

The dirt was from the cellar. The blood was from their victims. There had been seven, by her count—or at least that’s how many people the news had reported missing in the past few months. The police were baffled. No bodies had been found. Annabelle could’ve told them where they were.

Chad and Mark crept stealthily across the room toward her, tiptoeing across the creaky wooden floor. Chad had something in his hand. Even though it was too dark for Annabelle to make it out, she knew what it was.

The Shard.

“You heard it, too?” Chad said.

Annabelle nodded.

“Can you make it stop?” Mark asked.

Annabelle said, “No,” and Chad and Mark hung their heads.

Then she reached into her jacket pocket and took out the gun. It was her father’s .38 revolver.

She looked up into their blood-streaked faces.

“Wanna play a game?”

The police found the bodies a week later.

All three lay sprawled on the cabin floor, their heads surrounded by bloody halos.

Detective Russo crouched next to Annabelle’s body. The revolver was still in her hand. Even though her finger was no longer capable of pulling the trigger, the cylinder continued to spin around and around.

Across the room, one of the uniforms hissed in pain and dropped something on the floor.

Buy the Book

Shards

“Shards” copyright © 2021 by Ian Rogers

Art copyright © 2021 by Greg Ruth

My only complaint is that this should have been published on Halloween. :-) (And possibly it should have a warning in the intro, although the art pretty much does this). Reading this was like the thump of the tell-tale heart, each percussive note dropping in time with the tempo speeding to a rousing crescendo as each movement climaxed. It’s the Four Seasons of Horror. And on a personal note, I’ve only seen _Evil Dead: The Musical_ so having the entire story wrapped in the song made perfect sense to me! .

Well, that wasn’t disturbing at all. Nope. No nightmares here.

My initial reaction was “Oh, another story about a group of teenagers at a cabin in the woods.” But this story took that classic horror trope and built on it, until the anticipation was palpable. What a great read!

Wow, great read – thank you Ian and Tor!

Kudos: very creepy.

I didn’t need to sleep tonight