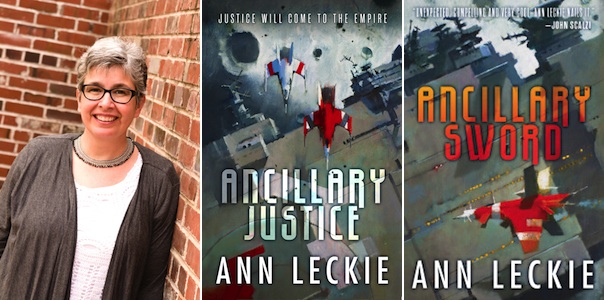

This week, we’re joined by the very shiny Ann Leckie, author of the multiple-award-winning novel Ancillary Justice, and the just-released (and just as good) Ancillary Sword. Ann was good enough to put up with my fangirling in person at Loncon3, and agreed to answer a few questions for us here.

Read her books, people. They’re really good.

LB: Let me start rather generally, by asking your opinion of how women—whether as authors, as characters, or as fans and commenters—are received within the SFF genre community. Have you seen change over the time you’ve been involved in the field?

AL: So, that’s a question I probably won’t have a standard answer to. When I was a kid, I had no perception whatever that science fiction was supposed to be a boys’ club. I was the only person in my elementary school who had the remotest interest, and since I was also lowest in the pecking order and the recipient of a good deal of verbal abuse, science fiction was framed as something weird that I did, not something “for boys.”

Then I went to high school, where I was treated much, much better by my classmates, and found no few fellow science fiction fans, but it was also an all-girls school. So, still no perception of SF being a guy thing. And there was no internet, and I had pretty much no contact with “fandom” or fanzines or any of the discussions or controversies that were happening at the time. I was just reading books and talking about them with my friends. Who were almost entirely other girls.

It was in college that I discovered that my being A) female and B) into science fiction was considered maybe kind of weird. But I still didn’t quite believe it. And though I had self-identified as a feminist since elementary school (oh, look, another weird thing weird Ann did!) I hadn’t actually noticed a dearth of women authors (everyone I knew in high school was reading McCaffrey, in college everyone was reading Tepper, and I’d grown up reading Norton who I’d figured out by high school was actually a woman). Nor had I noticed some of the ways misogyny manifested itself in SF (as in the wider culture—honestly, science fiction is not unique in this). Not that there wasn’t any imbalance there—just I hadn’t gotten to a place where I could see it very well.

So I have a personal history in which science fiction is something All Us Girls did. It still seems weird to hear someone say that women have only recently gotten into SF, or that really not many women read or write it, because that’s just not what I was used to seeing.

Still, as I got older and became more aware of discussions in the field—and aware of table of contents ratios, and review ratios—it became pretty clear that lots of people did think that, and that the same set of cultural forces and expectations that affected how women are treated generally were at work in science fiction too.

And the very first convention I went to—MidSouthCon, not sure offhand what year, but it will have been some time in the early 2000s—I went with a few (women) friends, and met a bunch of new folks (mostly women) and had a fabulous time, and then while I was checking out of the hotel on the last day, a reporter walks up to me and says, “Oh, look, a girl at the con! I’d like to interview you about what that’s like.” I had just spent the entire weekend surrounded by fabulous women! What the hell was he talking about?

So, anyway, in a lot of ways I feel like there’s been positive change—there are books and stories out lately that I suspect wouldn’t have sold in previous decades, and there are definitely changes for the better in the range of characterizations available in SF. I’m seeing a lot of awesome new women writers. But at the same time, there’s a sort of cyclical forgetting. Women have always been here in science fiction, and that fact gets trotted out whenever anyone tries to talk about the historic sexism of science fiction and the difficulties women face in the community, whether as writers or as fans, to prove that, no, SF wasn’t sexist at all!!! When, come on. But it seems like otherwise “women writing/reading science fiction in noticeable numbers” is always a new thing. It seems to me as though when it comes to women’s participation it’s like the proverbial goldfish’s three second memory. Except sometimes its a kind of selective three second memory.

LB: Speaking of “awesome new women writers”: Ancillary Justice. I feel it’d be a little like tiptoeing around the elephant in the room not to ask: how do you feel about the reception it’s received? And those—what, seven?—awards it’s garnered? What’s the best part, for you, about winning a Hugo Award?

AL: I feel…very strange. Like, it’s wonderful, and every now and then I look at the awards on my mantel and giggle a bit. Because, I mean, seriously.

I’m not going to pretend that I never fantasized about winning the Hugo. Or the Nebula, for that matter. I just never thought it was an actual real possibility. It was something I might occasionally daydream and then tell myself not to be silly and it was time to get back to work. Having it all turn out to be real—and on my first novel, no less, when I’d expected to maybe if I was lucky sell enough copies of Ancillary Justice to prevent the publisher from deciding not to go forward with Ancillary Sword… just, wow. It still feels like it’s not quite real.

The best part of winning a Hugo? Is… having a Hugo! Sometimes my tastes are very simple.

LB: Breq, your main character, is a person who used to be a sentient spaceship controlling multiple bodies and is now limited to a single body. Tell us a little about the Radch’s ancillaries and the challenges—and the most interesting parts—of writing characters with multiple bodies? (And characters who used to be spaceships, too.)

AL: I sometimes see people describe ancillaries as “reanimated” when in fact their bodies never died—if they had, they would be useless as ancillaries, actually. It’s the identity of the person who’s died, not the body itself. I’ve also seen “mind-wiped” used, but in fact this is never said in either book, and isn’t actually true. (Which I think becomes clearer in Ancillary Sword, not because at the time I wrote it I felt that needed clearing up, but because that particular… aspect of the story was always going to do that.)

I don’t go into a lot of detail as to how ancillaries work. Partly this is because a really big, crucial part of it is Sufficiently Advanced Technology. So there’s a level on which it just Works because the story demands it. But aspects of it I did think through fairly carefully.

The scariest, most difficult part of writing such a character was the most basic—I knew the story really ought to be in first person, but how do you convey that? What an alien experience, and how much information there would be to deal with at once! And the more I read about human physiology and neurology, the plainer it became that a being without a human body (or with many human bodies, or a large component of their body wasn’t a human body, not even close to it) wasn’t going to have human emotions, or human reactions to things. Having lots of human bodies in the mix does help with that, but raises its own questions and problems.

Of course, and perhaps it doesn’t even need saying explicitly, that was also the most interesting part. How do you even do that, how do you write from a POV like that? Really, once you ask the question, it’s difficult to avoid trying to answer it.

I answered it by, as I said, looking into human physiology and neurology. Not so much that I’d be taken for an expert, understand, but still. Looking at the question of what emotions are anyway, and where do they come from? What is identity, and how does anyone actually know who they are? And then I spent some time with questions of exposition. Which I suspect any SF and/or F writer will tell you is a consuming topic. If you’re writing spec fic, particularly certain subgenres of spec, the question of how to convey large amounts of information to the reader in a way that will serve your story is a really urgent one, and I’d bet money that nearly all SF/F writers at some time in their careers spend quite a lot of time thinking about it. (I’d bet this also goes for writers of historical fiction, and to some extent I suspect this overlap accounts for the popularity of, say, Patrick O’Brien among readers of science fiction and fantasy.)

So basically, a lot of the pre-work of Ancillary Justice was thinking about ways to organize and convey information that I knew the reader would need to understand the story. But if that wasn’t something I found inherently interesting, I probably wouldn’t be writing SF to begin with!

LB: So how do the ancillaries work, if they’re not exactly mind-wiped?

AL: Well, in theory—and of course with the support of a lot of Super Advanced Magic Technology—it’s very simple. As Strigan says, a fairly straightforward bit of surgery destroys the body’s sense of identity (in real life this is frighteningly vulnerable to the right sort of brain damage), some Super Magic surgery re-connects or re-builds those bits of brain tissue customized so that now this brain perceives itself as part of the ship. Add in more Sufficiently Advanced communications tech that keeps the signal constant between the ship and the various bodies, and you’ve got ancillaries. Oh, and of course you add in all the military enhancements.

So, actually, aside from the one hugely radical change, it’s really pretty simple. And some of this explains why some bodies never do quite adjust, or just aren’t suitable from the start. And yeah, it does raise questions about who, actually, Breq is, at least if you don’t want to take her own statement about that. But someone asked me several months ago, would the events of the book have been different if it hadn’t been One Esk Nineteen but another ancillary that survived? And I think, actually, they would. I think, moreover, that when Justice of Toren was hastily making plans to send one ancillary away to carry its message, it chose Nineteen quite deliberately. After all, it wasn’t the closest to the holds, or to the shuttle One Esk Nineteen needed to get away.

It also raises questions, of course, about who a ship is, with and/or without ancillaries. And how a ship might change over time depending on the bodies that are part of its body. It’s a pretty deep rabbit hole, actually, which makes it really interesting.

LB: There are a lot of rabbits down that hole…

Ancillary Justice has been compared to the work of a number of authors so far, from C.J. Cherryh and Ursula Le Guin to the late Iain Banks. Where do you think it fits in the grand tradition of space opera? What (and who) has had the most influence on you, both as a writer in general and in regards to the Radch books?

AL: I’d say my biggest influences are writers like Andre Norton and, particularly when it comes to the Radch, C.J. Cherryh. And there are writers who I’ve spent time deliberately examining with an eye to stealing their techniques. Vance would be one of those. You won’t learn tight plotting, or (gods help us) endings from Vance, but his language is gorgeous, and he does wonderful visuals. He had a sort of wry humor that I love. He also filled his books with different cultures, some of which were quite strange and alien while at the same time they were quite believable. You can absolutely buy people doing something like that! He’s not without his flaws, but who of us is?

As to where Ancillary Justice fits in the tradition of space opera… I’m not sure? I’m not sure I have a fixed map or a hierarchy or anything, I think of it more loosely. Or sometimes I think of it like a big family, with aunts and grandmothers and cousins, and everybody’s related some way or another but it can be complicated to work out just how and mostly it doesn’t matter except as idle conversation at the reunion. I feel like it’s a book with a lot of mothers and grandmothers—Norton certainly, Cherryh absolutely, and all the writers whose works I found at the Carpenter Branch of the St Louis Public Library during my many Saturdays there, most of whom I wouldn’t remember unless you brought up a specific title, because I spent a lot of Saturdays at the library.

I am occasionally surprised at how frequently Ancillary Justice is compared to Banks. But of course, he did the ship AI thing, so that makes sense. But I think that similarity is mostly superficial, and he was doing something quite different. I mean, in terms of his overall project. And as it happens, I’ve only read Consider Phlebas—quite some time ago, actually—and, after I sold AJ, The Hydrogen Sonata. I enjoyed both of them, of course. But they’re not part of me the same way that, say, Cherryh’s Foreigner books are, or the way Norton is. And I wasn’t responding or replying to Banks, in the way writers sometimes do, either. But of course, Banks was one of the greats. The world is the poorer for his loss.

LB: It strikes me that Banks was interested in interrogating utopias—especially the failure modes of utopia—while in Ancillary Justice and Ancillary Sword you’re more engaged in interrogating… well, imperialism, and assumptions about colonialism and identity and power. Was this something you actively set out to do?

AL: Not at first. At first I just thought it would be cool to write a story about a person who was a spaceship, and a Galactic Empire ruled by a person with thousands of bodies who could be in lots of places at once. I mean, how shiny would that be? Right?

But those characters were going to be difficult to write. So difficult that I delayed actually starting on what became Ancillary Justice for years. In the end, that was an advantage. The things I did write in that universe allowed me to work much more carefully on the construction of the universe itself.

And by the time I was nearly ready to actually begin, I had run across a lot more discussion about colonialism and imperialism. And of course, questions of power and even identity are important parts of that discussion. And I had begun to develop a writing process that relied (still relies!) a lot on having my basic idea and then taking it as seriously as possible. I mean, really, if I’ve imagined X, what would that really mean? What’s interesting about X, does X have parallels in the real world, and if so what are they actually like? And of course, when you go that route with X being a Galactic Empire, and characters with multiple bodies, well, where does that lead? It leads to me having to ponder questions about imperialism, power, and identity, that’s where.

So, I didn’t start out thinking about them, but I ended up there. It was very much a learning process. And kind of random in some ways. I remember not long after I’d tried to actually start a first draft, hearing someone utter the phrase “the colonized mind” and I was like, “Oh, wait, what? Tell me more!” Because, I mean, right?

LB: We haven’t yet touched on your choice of Radchaai pronouns. A lot of people have likened your choice here to Ursula Le Guin’s in The Left Hand of Darkness. Some people have found the use of “she” alienating or puzzling. What were your goals here, and do you think you succeeded with them?

AL: So, my original goal was to portray a society that genuinely did not care about gender. Using a single pronoun for everyone was just one part of that, but the more I played with it, the more interesting the effect was. Ultimately, of course, using “she” for everyone doesn’t actually convey gender neutrality, and I realized that pretty quickly. But I think if I’d chosen to use a gender neutral pronoun—e, or sie, or zie, or any of the others—it would have produced an interesting effect, but it would have lost the way that “she” automatically goes straight to the reader’s perceptions. No, that’s not the best way to say it. I mean, the very long familiarity long-time English speakers have with the pronouns “he” and “she” means that we react to them without actually thinking much about it. We don’t stop to ask ourselves what they mean, they just go right in and trigger a particular set of associations, almost automatically, unconsciously. By using “she” for everyone, I get (for many, but of course not all readers) the effect, once those associations are triggered, of undermining or questioning them, in a very basic way, a sort of… experiential way. It’s one thing to tell someone about the masculine default, and have them understand the idea. It’s another thing to actually demonstrate how it works on your reader. But it only works (for the readers it worked for, because of course it didn’t work for everyone) because we parse those pronouns so thoughtlessly.

The various gender neutral pronouns don’t have that long familiarity for most of us. The effect I mention above, which quite a few readers have explicitly commented on and appreciated, would have been lost if I’d used one of them. It was a trade-off, I think. I can’t blame folks who wish I’d used a gender neutral pronoun instead, of course, and I’m hoping to see those pronouns used more so that they become more generally familiar. I’m seeing singular “they” for known people (instead of the nebulous “don’t know who this might actually be” use of singular they) used well in short fiction lately, and I’ve been really happy to see it. But myself, for this particular project, I think the effect that I got, at least with a sizable number of readers, was worth the trade-off.

So, in some ways I succeeded. In other ways I didn’t. But the result was interesting and gave a lot of people something to think about and discuss, and I’m glad of that.

LB: With Ancillary Sword out this month, have you any hints to give us about the next book? And have you plans beyond that one? Can you tell us about your ambitions for the future?

AL: So, the next book. Well. Hmm. Well, how to say much without spoilering Ancillary Sword? I will say, there are plenty of questions needing answers by the end of AS. Questions like, what’s up with the Ghost Gate? How are the Presger going to react to, you know, that thing that happened? How long are things going to stay quiet before the fighting reaches Athoek? Why do I seem to not have any tea, and how can I change that? No, wait, the answer to that one is obvious.

After that? I have no idea! The universe these books are set in is nice and large, though, plenty of room to play in. Probably once I’m done with Ancillary Mercy I’ll start eyeing some bit of it that I haven’t done much with and thinking of something to do there.

Ancillary Justice and Ancillary Sword are published by Orbit.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.