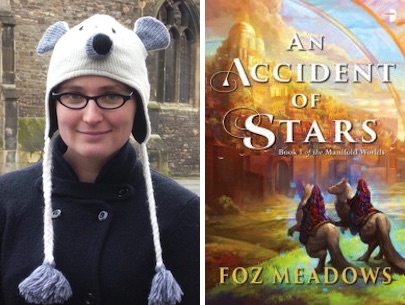

Today, we’re joined by Australian author, critic, and award-nominated writer Foz Meadows, whose recent novel An Accident of Stars is a gorgeously epic portal fantasy.

If you haven’t picked up An Accident of Stars yet, you should. It’s a story all about costs and consequences and the families you make, or choose. It’s one of my favourite books of the year, so I’m really happy that Meadows agreed to answer some questions…

LB: What is the most awesome thing about An Accident of Stars?

FM: The most awesome thing about An Accident of Stars is that I finished it with my sanity largely intact. Which is not quite as much of a joke as I’d like it to be, really. For all that it’s a book inspired in no small part by the tastes and wants of my younger self, I wrote it during one of the hardest periods of my life, and that comes across—to me, at least—in the themes of survival and adaptation. It’s an escapist fantasy in the sense that the protagonist, Saffron, finds herself in a different world, but at base, it’s a search for meaning. As a kid, I always loved portal fantasies as a concept, but I hated how the return journey always seemed to wipe the slate of anything and everything the characters learned while elsewhere, nor does it seem coincidental that this happens mostly to women. Dorothy spends her time in Oz wanting nothing more than to come back home; Alice wakes from Wonderland and thinks it’s all a dream; Susan Pevensie is barred forever from Narnia for the sin of wanting to be an adult woman. But somehow, those same strictures never seemed to apply to men. In the original Stargate movie, Daniel Jackson stayed behind to explore his new world; so did Jim McConnell in Mission to Mars. In the reboot of Doctor Who, I loved that Rose, Donna and Martha were allowed to feel the tension of travelling with Doctor while trying to maintain their lives at home, but none of them end up exploring the universe without him the way that Captain Jack Harkness does, their subsequent adventures—however extraordinary—keeping them Earthbound. And with An Accident of Stars, I wanted to do something different to that: to write a story about women who whose adventures in other worlds don’t leave them idealising home, but questioning what it means.

LB: All of the viewpoint characters are women. Was that a deliberate choice, or did it “just happen” that way?

FM: It just happened that way. I default to writing women unless I’m writing about queer men, and even then, I still wind up including ladies. It’s not that I’m wholly uninterested in stories about men in general or straight men in particular, as my reading and viewing habits will attest; it’s just that they’re so much the cultural default that, when it comes to my own writing, I incline in other directions. Partly, that’s because I’m interested in writing different cultures—by which I mean, dreaming up new cultural permutations and exploring how they might work, which is inherently subversive of our own cultural imperative—but mostly it’s because I grew up with precious few representations of characters who felt like me but a surfeit of characters who, it was implied, I ought to have identified with, and yet who I didn’t quite recognise, or whose woodenness was an insult, or who, though real, were barely on nodding terms with what I really wanted. And because of that, it’s taken me a long damn time to articulate that wanting, or acknowledge all its subtleties—but now that I have, I see no reason to try and walk it back.

LB: Several years ago, you published two young adult novels, Solace & Grief and The Key to Starveldt. What is the biggest difference, would you say, between writing them and writing An Accident of Stars?

FM: I know myself and my craft a lot better now, is the obvious change. I’m proud of Solace & Grief and The Key to Starveldt, because—well, I wrote them, I worked hard to see them published, and because they represent my breaking into the industry. They were honest books when I wrote them, and in terms of magical concepts—notably portals, dreams and internal landscapes—there’s a lot they share with An Accident of Stars, if only because those are ideas in which I’ve been consistently interested. But they were also written and conceived in the period just before I began to understand who I really am as an adult, before I started actively engaging with tropes and criticism and gender and everything else I’m now, kind of, known for discussing. Both personally and professionally, I wouldn’t be who I am if I hadn’t written those books, and for that reason, I owe them the same immense debt all authors owe their first novels. That being so, the biggest difference between then and now, really, is the same difference you’re always going to have from one novel to the next: by virtue of time being linear, each book is always a lesson in how better to write the next one. By the very act of writing a novel, you invariably turn yourself into someone who, given access to time-travel, would’ve written it differently: Foz-Then couldn’t have written An Accident of Stars, but because she wrote Solace & Grief and The Key to Starveldt, Foz-Now could. And I think that’s kind of awesome.

LB: You’re very active on Tumblr and as a writer of fanfic as well as an award-nominated blogger. How does your fan writing and criticism inform your original fiction, if it does? How does your fiction inform your fan writing and criticism?

FM: Writing fanfic has improved my writing in innumerable ways, none of which I anticipated at the outset; I can’t recommend it highly enough as a fun means of professional development. One of the hardest, most dispiriting things about writing is how long it takes to get published—not just in terms of working towards a professional debut, which is the obvious example, but the weeks, months or years that routinely pass between the completion of a story and its public availability. It gives you a lot of time to doubt whether what you’ve written is any good, to second-guess and over-edit and generally turn into a nervous wreck, all while wondering—especially in short fiction markets—if your story is going to provoke any commentary or reader reactions at all. This is why so many writers join writing groups, which can be great support networks for offering critique and affirmation in the mean time; it’s certainly something I’ve done myself, and I’ve learned a lot in the process. But the fanfic community is another beast altogether: there’s an immediacy to it, a passion and dedication, that’s unique in my experience. Because people already care about the characters, you’ve got a pre-existing readership, and because you can post immediately, there’s an instant incentive to write quickly, knowing that someone, somewhere is waiting to read it. I’ve written vast quantities of fanfic faster than I’ve ever written original fiction, and I say that as someone who was never a particularly slow writer to begin with. Publishing a long fanfic chapter by chapter, having readers eager for each new update, taught me more about how to solve plot problems on the fly than workshopping ever did, and while there’s less of a tradition of concrit in fandom spaces than elsewhere, the focus on positive feedback helps you develop the confidence to write and submit, write and submit, which is undeniably one of the most important skills to have.

And because fandom is so minutely concerned with subversion, tropes, gender, sexuality—because there’s such an emphasis on the kinds of stories people want to see, as opposed to the kinds of stories that predominate elsewhere—it gives you a great deal of freedom to take your original works in different directions. Paying attention to fandom meta and commentary has absolutely made me a better critic, which in turn has made me a better writer. I’ve still got a lot to learn, of course, and always will—see above, re: constant linear development from one book to the next—but if writing my first novels taught me that I could be a professional writer, it was fandom that helped me figure out the kind of professional writer I wanted to be.

LB: What fandoms are you most interested/active in at the moment? Could you tell us a bit about why?

FM: Dragon Age owns my entire ass, that’s not even an exaggeration. I’m twenty fathoms deep in the twin dumpsters of Supernatural and Teen Wolf, and at this point, it’s so much of a community thing that I might as well declare myself fandom-married to garbage. I’m super excited by Steven Universe and Sense8 and The 100, though the third season of the latter has kinda burned me out before I’ve even watched it, and there’s a bunch of other stuff I love, but basically, those are the big ones. They’re not perfect narratives by any means, and I’ve written great swathes of meta about why that’s so, but in every case, there’s something about the characters and the world that makes them feel personal. Trying to explain why you love something is always a bit like bearing your soul, but even when I’ve been angry at the narrative or the writers—even when fandom arguments start to blow up, as they invariably do—I’ve never stopped caring about the stories. There are friends I’ve made because of fanfic and fandom that I’d never have known otherwise, and just knowing there are people who care as much about this stuff as I do is always comforting.

LB: What other writers and their works have influenced you, if any?

FM: SO MANY WRITERS. Seriously, it’s pretty difficult to sit and name them all, but I will say that I’ve been influenced as much by writers whose work I disliked, or of which I’ve been heavily critical, as writers whose stories I love. As inspiring as it is to reread my favourite works or discover something new and wonderful, part of the joy in those novels is the knowledge that I couldn’t have written them: that I’m allowed to just be an audience, rather than running constant mental commentary about what I would’ve done, or failed to do, if given that idea. Whereas books you nitpick or hate, but which have the seed of something interesting in them? That’s inspiring in a different way: the impulse to write your own version, to tease out a different thread of narrative. My very favourite stories are ones where, all headcanons and fanfic impulses aside, I can’t find any crack in the narrative that makes me want to write that premise, or part of that premise, differently: where I’m just content to play in that world as a sandbox and accept the core concept as is. Those are inspiring because they show you what the genre can be. Other stories are an influence because they teach you the tropes you most want to subvert, even if you still love them in their original form, or because they make you so angry that you want to write something different. It’s not enough just to have an idea of where you want to go as a writer: you have to actively think about how you’ll get there.

LB: Are there one or two recent favourites you might care to mention?

FM: The Goblin Emperor, by Katherine Addison. I’ve now read it four times and it never stops being amazing; it’s effectively my go-to comfort book. Fran Wilde’s Updraft is also excellent, as is Kate Elliott’s Court of Fives, N. K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season and Ann Leckie’s Ancillary trilogy. There are more, but those are the ones that immediately spring to mind.

LB: Last question! What’s on the cards for you right now? Any hints about the sequel? What else might we hope to see from you?

FM: Right now, I’m on deadline to finish A Tyranny of Queens, the sequel to An Accident of Stars. I don’t want to say too much about it at this point, except that it’s concerned with two main questions: what happens to a worldwalker who tries to go home, and what does ‘home’ really mean? I’ve also been working on some queer fantasy romance, which I’m really excited about, as well as drafting a YA novel about dragons, because I’m me. But all that’s in the future—right now, it’s deadlines ahoy!

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.