Ordeal in Otherwhere takes us back somewhat circuitously to Warlock, this time with a female protagonist. The story opens in a very similar way to Storm Over Warlock: our viewpoint character is running away from a disaster and struggling frantically to survive. This time, it’s a young woman, Charis Nordholm. The antagonists are human, the planet is a new colony called Demeter, and the disaster is a plague that attacks only adult men. The closer those men are to the government service, the more likely they are to contract the disease.

Charis is a service kid, following her father around from post to post. Her father, Anders Nordholm, has died, without any great emotional outpouring on Charis’ part; mostly she’s preoccupied with staying alive and out of the clutches of the extreme religious conservatives who have taken over the colony. She succeeds for a while, but naively lets herself be captured when a spacer lands and turns out not to be the rescue she expected.

The spacer is a free trader of low status and questionable ethics, who essentially buys her in return for getting her off-planet. He stows her in his very retro, rattly, submarine-like rocket ship and fairly quickly sells her to another and even dodgier spacer who needs a woman to serve as a trade negotiator on a planet ruled by alien matriarchs.

The planet is Warlock and the aliens are our old frenemies the Wyverns, or witches. The situation there is even more complicated than it was when Shann Lantee and Ragnar Thorvald made first contact with the Wyverns: There’s a trader trying to stake out trading territory, an apparent pirate invasion, and internecine conflicts within the Wyvern culture, whose females have kept their males under psychic control for generations.

The males, it turns out, have rebelled and joined forces with a group of Terrans; it also turns out that those Terrans are a corporate takeover masquerading as a pirate invasion and a trade mission. The company has a machine that blocks the Wyverns’ mind-control Power and allows the males to escape the females’ control.

While Charis is struggling to negotiate this minefield of cultures and crises, she connects with a small, cuddly, and telepathic alien animal, the curlcat Tsstu. She also makes contact with Shann Lantee and his male wolverine—the female has had cubs and is not playing the mind-control game, thank you. The Wyverns help her escape from the trading post and bring her into the Wyverns’ Citadel, where in the course of two very quick pages she learns all about the uses and abuses of their psychic Power and gets her very own magical coin-cum-teleport button.

Many authors would have built the whole book around this training sequence, but Norton has never cared much about how magic works. She’s more interested in quests and adventures, with lots and lots of dream sequences and psychic journeys through weird alien mindscapes.

That in fact is what “Otherwhere” is: it’s the psychic realm in which the Wyverns spend a great deal of time, and to which they condemn enemies and send their young for training and testing.

Exactly why the Wyverns give Charis their Power and train her to use it isn’t terribly clear; they quickly decide all Terrans including Charis (and Shann and Thorvald) are The Enemy because of the ones who have helped the males rebel (and besides, Terrans all males except for Charis, which is a double whammy). By this time Charis and Shann and the animals have formed a four-way bond, and they’re determined to shut down the invaders and help the Wyverns—though again, that’s ambiguous; the Wyverns are more than a little hostile and not particularly reliable as allies. Plus there’s the part where they turn their males into robot zombies.

Shann decides he has to take point in finding the Power-blocking machine (which its users call the Rim), with the animals and Charis outside as backup. He’s quickly captured, and Charis isn’t able to get him out. She has to leave him (with far more emotional wrenching than she ever felt for her dead father) and go back to the Citadel and try to get the Wyverns to help free him. In the process she frees Thorvald from his own imprisonment—poor Thorvald spends most of his time being held prisoner by Wyverns—and gets him to help her. She also persuades a Wyvern elder to back them both up, and enlists the animals to get her as far as the enemy camp.

Once inside the Rim, she takes her cue from the only other human female on Warlock, a woman brought in earlier to serve as a negotiator, who went insane with xenophobia—mostly she rambles incoherently about “Snakes.” Charis was her replacement. While feigning mental illness and overall feminine frailty, she discovers the truth of the corporate takeover, finds Shann and liberates him from his state of psychic catatonia, meets the Wyvern males who are guarding the Rim device, and hooks up psychically with the animals and Shann and, at a distance, the Wyverns. They break the Rim device, arrest the corporate raiders, and with great difficulty persuade the witches to at least consider the possibility of allowing their males to have free will. The males aren’t terribly keen on this, either, but as the Terrans take care to point out, if the two sides don’t come to terms, there won’t be any more Wyverns.

In the end, Charis and Shann get it together—with each other, and with the curlcat and the wolverines. It’s a multi-gender, multi-species unit that uses Wyvern Power as a jumping-off point for an entirely new and expanded range of psychic abilities. They don’t even need magic coins. Charis has figured out how to use the Power without them.

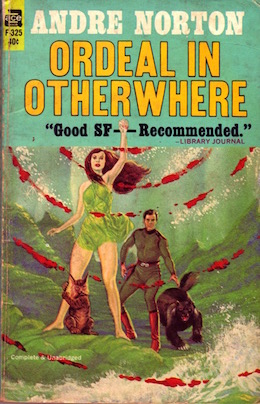

This is a headlong, rip-roaring page-turner. It’s classic late Golden Age planetary adventure, and it’s both dated and subversive. The tech is rather gorgeously retro, with rocket ships that come down upright on fins and hum and rattle inside like spacegoing submarines, spacers in heavy magnetic boots (no null-g here) and “space tans” from all the radiation that the ships don’t shield them against, and minimal communications capability aside from the aliens’ telepathy. They have blasters and stunners, and the Rim device, which is apparently an alien artifact that the company found somewhere and rather accidentally figured out how to use against the Wyverns. The Fifties sci-fi film aesthetic is alive and well here, with shades of Lost in Space. The creature comforts of Star Trek’s Federation ships were still a few years away.

Here for the first time in this series we have an actual human female, and better yet, she’s the protagonist. But she’s a Smurfette.

She’s the only functioning female on Warlock—her predecessor is mentally ill and incapacitated—and on Demeter we only hear about the women as an undifferentiated mass who are too weak to take over Strong Male Jobs like clearing land. Charis is the exceptional one, the educated woman among the ignorant fundamentalists, and she has no mother. She only has a father, whose name sounds like a wicked little authorial joke. Anders Nordholm, Andre Norton. Charis’ progenitor, Charis’ creator.

For all we know, Charis, like Shann, was grown in a vat. Or sprang full-armed from her father’s forehead.

The Wyverns are so profoundly sexist that they take her right in and teach her solely because she’s female, though later they decide she’s Terran like the males of her species, so she must be Bad. They have no use for males at all, except for making babies. Their males are kept in a permanent state of mental slavery.

And that makes me wonder a couple of things.

Andre was more than old enough to have seen the women of World War II stepping up for the men who were off to war. Rosie the Riveter and her sisters proved that women could handle any job a man could—which was a radical cultural shift from the time when women were not allowed to participate in strenuous physical activity because it might damage their delicate lady parts. But come the Fifties, Rosie and company were tossed out of the workshop and back into little ruffled aprons and looking pretty for Him.

Now of course we know what women can really do, and these attitudes are quite out of date. But then there’s Charis, who doesn’t make a lot of noise about how strong and tough she is. She just goes out and does what she has to do. She’s an easy match for the Wyverns, though her naivete allows them to control her in more ways than streetwise Shann would allow—but that’s not a gender thing, it’s an upbringing and education thing. Charis was raised to privilege and has appropriate gaps in her knowledge worldly wisdom.

The problem with this is that Charis is a one and only. She has no female friends or role models. The Wyverns are part teachers and part adversaries, and all alien. Her closest companion for much of the adventure is an alien cat (also female, but no more human than the Wyverns and somewhat harder to access mentally).

The big final hookup is suprisingly non-binary: human male and female (which is conventional as far as it goes) plus alien cat plus wolverine family. It’s a cross-species poly relationship, while also managing to be suitably Fifties cis-het.

The gender politics in this series so far is kind of difficult. Terran society is totally male-dominated. Males and females, both Terran and alien, have nothing in common—the Wyverns are just as segregated as the Terrans, only with the genders reversed. Charis and Shann do get it together, but it’s distinctly non-sexual. It’s a mind-bond, and gender doesn’t seem to have a lot to do with it.

I found myself wondering as I read, if Norton was aware that she had set up a parallel between Terran and Wyvern gender roles. If Wyvern males are mind-controlled into near-non-sentience, and are viewed as incapable of rational thought or action…what does that say about all the Terran females we don’t see?

And then there’s the plague that takes out all the adult males on Demeter, starting with the government employees. Of course the remaining males clamp down hard on the patriarchy and sell the one educated female into slavery, but the subtext there is interesting. I could see the rest of the adult males succumbing to a second wave of plague, leaving the women to sort things out and, one hopes, raise their sons to respect the now dominant, and majority, gender. (Not to mention, if they all die off after puberty, just think of what the women have to do to keep the population up—the Wyverns might not be the only ones who keep their males for one thing and one thing only.)

Charis is mentally stable and by no means physically weak, and she takes these aspects of herself for granted, but she’s an outlier. She was raised by a male and separated by education from the females she lives among. The logical conclusion is that most Terran females are no better regarded or treated than the Wyvern males—and that, given opportunity, they might be just as eager to break the chains and go their own way.

It’s interesting that the feminist revolution was just beginning in the US, right about the time this book was written. It’s almost as if Norton foresaw the revolution, though dimly and through a heavy filter of male supremacy.

I’m off to Forerunner Foray next. More female protagonist! More telepathic animals! More alien planets and mysterious mysteries!

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her new short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published last fall by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.