…and why wouldn’t you? Book collecting is one of the greatest hobbies there is. It combines beautiful, interesting objects with the excitement of the hunt and, who knows, maybe even the possibility of making some money! Worst case scenario—you wind up with a lot of books. There’s no way to lose.

Still, this is a decision. Collecting isn’t just hoarding—randomly accumulating lots of books is no bad thing, but collecting requires a slightly more strategic approach. You need to figure out what you want, why you want it and, perhaps most importantly, what you’ll do to get it…

First, figure out why you’re doing this

And, speaking as a die-hard bibliophile, “because I can’t imagine not” is a perfectly acceptable answer. But maybe you see books as a long-term investment, like wine or stamps. Or perhaps you’re after a quick profit—eBay, dealing, etc. Or you simply love an author, his or her books express your inner philosophy and you need them all, on your shelf, for you.

All of these reasons are great, but they will impact what sort of books you’re looking for, as well as what condition they’re in—new, used, signed, inscribed, etc.

Second, pick a theme

I chose “theme” not “topic” deliberately, because what you collect can be something more intangible – perhaps even a category that may only be specific or identifiable to you.

It will also matter whether you pick a tight theme, say, the works of Joe Abercrombie or a broad one, e.g. “grimdark fantasy.” The benefits? Well, with Abercrombie, you can achieve it. Despite his best efforts, there’s still a finite amount of Abercrombiana (Another perk of book collecting: coining silly words like that). The idea of completing a collection is kind of cool, if slightly harrowing the instant a new book comes out.

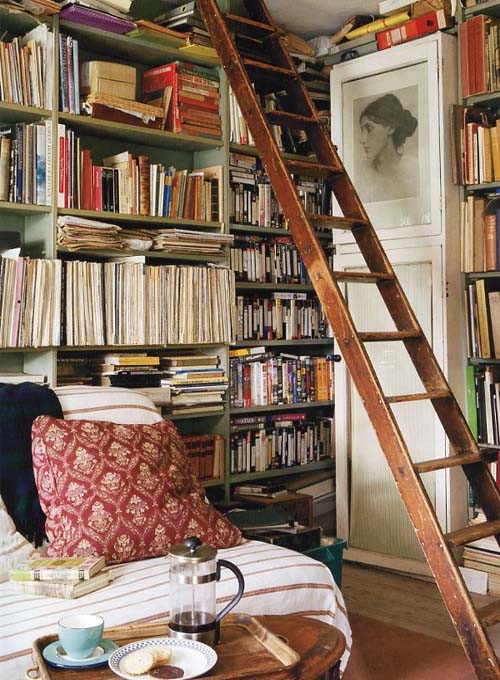

With a broad collection, you’ll never finish. That can be frustrating, or fantastic. The broader the theme, the more likely you are to find something for your collection: every flea market, bookshop trip or lazy eBay browse will reveal something new for your ever-growing shelves.

I’d also warn against going too broad. Collecting, say, “fantasy” is dangerously woolly. You’ll not only never achieve it, but you’ll go broke trying. Boundaries keep you sane.

From personal experience: I stumbled on two of Maxim Jakubowski’s Black Box Thrillers—just as reading copies. Then I found a third. Then I did some research, and learned there were only nine. So, you know, why not? The quest began, and, within a year, ended. Awesome. Satisfying. Now what? Fortunately, I’m also after Fawcett Gold Medals, and, at last count, there were an infinite number of them. Whew.

Themes are also a matter of, for lack of a better word, “geometry.” Any two points make a line, and then whammo, you’ve got a potential collection. For example, multiple books with the same cover artist. Period typography. Publisher. Setting. Anything. Again, this can drive you mad—if you declare “COLLECTION” every time you get a pair, you’ll go nuts. But this can also be wonderful—when you make a link between a few books—perhaps even a link that no one has ever thought of before—and think, “hey—collecting William Gibson means I’ve got a few books with advertising in them. I wonder what other science fiction books are about marketing?” or “Hmmm. I love Hammett, clearly I need more San Francisco noir.” Be prepared for your themes to spiral out of control—and that’s part of the fun.

Of course, the answer is always be interested in everything. But that’s why we’re readers as well, right?

Now… are you looking for value or completeness?

Is it more important that you get all of Ursula Le Guin’s books? Or do you want the best copies of her books? You can approach a collection either way (or, of course, both ways).

Is it more important that you get all of Ursula Le Guin’s books? Or do you want the best copies of her books? You can approach a collection either way (or, of course, both ways).

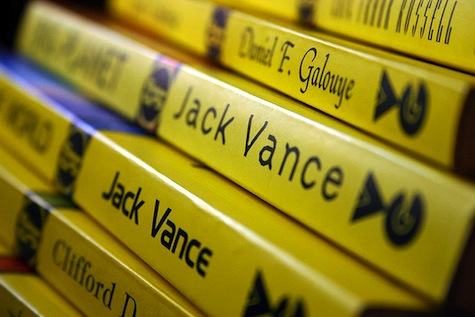

Imagine an author like Le Guin or Stephen King, or a theme like Ace Doubles or Gollancz yellow jackets. Just having one of everything would be an incredibly impressive achievement. Alternatively, you could ignore all Ace Doubles that aren’t mint. Or Gollancz yellow jackets that aren’t first editions. It ties back into what you want out of your collection: do you want to read everything or to own it?

What does “value” mean to you anyway?

It helps to think about books in several ways:

- As a text. The object is insignificant; getting its content, however, is important. This ties in with the idea of completeness—the book is valuable because you want what’s inside it, not necessarily the physical package.

- As an object. You may never read this book. It is not a text—it is a squat, rectangular sculpture, there to be admired, not put to a practical purpose. A first edition is more valuable to you than a later printing; a mint first edition is more valuable than a battered one. Finding dust jackets (unclipped, of course) is important. Mylar book covers are essential.

- An a historical artifact. This book has a story of its own. Maybe it is from the collection of another author, or your own grandmother. Possibly the previous owner left fascinating and enigmatic annotations. Perhaps it has the bookplate of a publisher, or is an ex-library “file copy” from the British Museum or the BBC. The value is in the unique story that this copy has to tell.

“Value”—either tangibly expressed as money or intangibly as an emotional connection—can stem from any one of these.

Deep question: is it more important to search or to find?

This sounds a bit abstract, but, seriously: book hunting just so you can hunt for books is a perfectly acceptable way of going about it. You should think about what’s fun for you.

With Amazon (either normal or Marketplace) and Abebooks, you can essentially home in on any book you want, and get it with a single click. Does that increase or decrease the fun you’re having? Those two sites are at one end of the spectrum. On the other end lurks pure serendipity: flea markets, dealer rooms, charity shops. In-between: wandering into Foyles, Forbidden Planet, mailing lists from dealers and small bookshops. It is really up to you.

Again, a personal example: I’m missing one John D. MacDonald. One. Dude wrote a billion books, I don’t have one of them. I know exactly which one (I’m not telling) and I could click and get it right now for $20. But my JDM collection started with a box of copies that I got for a nickel each from a Phoenix restaurant (yup). I’ve spent years on it, and buying the last one with a click of the mouse? That just feels like cheating. I’m finding it through blind luck or not at all.

Signed stuff is awesome, right?

Again, that’s all up to you—but, generally speaking: yes. If you think of the three ways to add value—signatures give a book monetary value, they turn it into an endorsed text (the author is approving it after all) and they give that copy a story of its own.

Often the big question is whether to get something flatsigned (a signature) or inscribed (“To Jared”). Other variations include “S/L/D” (signed, lined and dated—which means the author includes a quote and dates the book to the time of signature) or doodled/sketched (exactly what it sounds like) or even a presentation copy or warmly inscribed (in which the author actually sounds like they knew the person who is receiving the book, e.g. (“To Jared, thanks for the scarf, now get off my lawn”).

A few tips:

- Getting proofs signed (not inscribed) often says, “I got this copy for free, now I’m going to put it on eBay and make a lot of money off of it!” Not every author cares, but some do, and I don’t entirely blame them. I always get proofs inscribed—a way of saying that your copy will never leave your possession.

- Inscriptions do lower the resale value, so if you’re getting a book signed in order to resell it, think twice. Unless you know a lot of people named “Jared.”

- There are exceptions. If the inscription is to someone famous, for example. That’s an association copy (a book that also has value by association with someone/thing). “To Jared” devalues a book. “To Patrick Ness” doesn’t. Also, over time, the price disparity between signatures/descriptions becomes less noticeable, and, after a hundred years, generally doesn’t matter. (That may seem like ages, but we’re really talking about books from 1913 and earlier.)

What can help?

The best tools will always be Twitter and Google, because a million other collectors are all lurking out there, and dying to answer questions. But I would suggest some basic stuff—for example:

The best tools will always be Twitter and Google, because a million other collectors are all lurking out there, and dying to answer questions. But I would suggest some basic stuff—for example:

- Start a catalog. You’ll want to set this up sooner rather than later, as going back and filing stuff can be a pain in the ass. I use Collectorz’ Book Collector (there’s a free trial, so you can see if it is to your taste). I also have friends that use Google docs, Excel spreadsheets, GoodReads, LibraryThing, even manual checklists.

- Start a portable catalog. This comes in handy before you know it. Honestly, “want lists” are nice—and extremely useful when you’re dealing with online booksellers and the like. However, in my experience, you’ll probably get to the point where it is more useful to know what you have than what you don’t have pretty rapidly—especially with broader themes. This keeps you from buying duplicates. Most of the electronic catalogs now have apps (like Collectorz) or mobile sites (like GoodReads) which are really helpful.

- Learn how to identify first editions. Else you will be hosed by dealers, auctions and the like. There are a lot of great lessons on this subject on the internet, but I really do recommend getting a pocket sized guide like one of these. You won’t need it forever, but you’ll find it handy for the first few fairs or conventions.

- Learn how to identify other editions as well. Book Club Editions are often sold as first editions, and can be almost identical—but are often slightly different sizes and won’t have prices on the dust jackets. And if something is “Ex-Library” there’s a reason it is being sold for 10% of its real value. If you just want it to have a copy of the book, go wild. But it’ll be ugly.

- Consider other references. FIRSTS magazine is fun, and worth flipping through, but unless there’s an article immediately relevant to my interests, I wind up tossing them out pretty quickly. There are loads of checklists and books and guides—both as websites and in print. Again, my personal experience: if there’s a big thing I’m collecting, say Ace Doubles, it helps me to have a reference, if only to have a complete checklist. But general guides? Not so helpful. A lot of people swear by Joseph Connelly’s Modern First Editions, but, honestly, it is trying to cover everything in a single book (and does very little genre, incidentally). When you’re going for breadth: just use the internet.

Finally, remember that there’s always one more.

If you go into this thinking that you can “win” and have the definite collection of something, you’re just going to wind up frustrated (and poor). It is more important to turn this on its head: collecting is something you can do forever; there are always more books to find and opportunities to grow your own stash of treasures.

As a corollary to this, be proud of your books—you found them, you did a great job. But don’t be a dick about it, because, you know what? There’s always someone with more.

Ok, I know there are a few other collectors out here… what would you advise? Tips? Tricks? Philosophies? Games? Share!

This post originally appeared on Pornokitsch on August 28, 2013

Jared Shurin wants all the books.