The character of Solomon Kane is another one of Robert E. Howard’s seminal sword & sorcery creations. Unlike Conan and Kull—two of Howard’s creations I’ve discussed in recent posts—Solomon Kane is neither barbarian nor king. Instead, he’s a Puritan adventurer traveling through Europe and Africa during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Armed with his sword and pistols, he battles wickedness in the name of God wherever he encounters it. Sometimes this means fighting common brigands and pirates, and other times it means pitting his wits and brawn against black sorcery. He is a bit like Marvel’s Punisher, in that whenever possible Kane deals out death to those he considers evil. The main difference between them in terms of psychology is that Kane believes he’s doing God’s work. Kane always strives to do good as he sees fit. The wonderful twist to this avenging angel of goodness is that Howard makes it abundantly clear that Solomon Kane is a functioning madman.

Like Conan and Kull, Solomon Kane made his first appearance in the magazine Weird Tales, in the August 1928 issue, with the story “Red Shadows.” In his lifetime, Howard would sell 7 Solomon Kane stories. A poem about Solomon Kane was also published several months after Howard’s death and was presumably bought beforehand. As with his other creations, a host of unpublished material about this character would find its way into print in the decades following Howard’s suicide.

On the surface, it’s clear how this sword & sorcery hero differs from the others I’ve discussed. All you have to do is consider who he is, what he stands for, and the milieus in which his stories take place. But there are deeper, more intriguing aspects to the character of Solomon Kane. The truth is that of Howard’s most enduring creations, Solomon Kane is not just the most fully developed character (although I admit Conan remains my favorite), but he also offers the deepest glimpse into the tortured soul of Robert E. Howard.

Any examination of Solomon Kane should start with the character’s name. Besides having an evocative ring to it, it also offers the perfect summation of this puritan madman. As I mentioned above, when Solomon Kane kills the wicked, he believes he is doing God’s work. With this in mind, consider the name Solomon. The first mention of this name comes from Biblical times in the Old Testament, in the form of King Solomon. Solomon the Wise …Solomon the Just …Solomon the Judge. “The Wise” doesn’t really apply to Solomon Kane. “The Just” & “the Judge” should. Solomon Kane believes he is meting out justice each time he casts judgment upon the wicked and seeks their deaths. Now consider the name Kane. This is a variation of Cain, which again brings us back to the Old Testament. Cain & Abel were the sons of Adam & Eve. Cain killed his brother Abel out of jealousy, committing the first murder among mankind. Jealousy isn’t part of Solomon’s Kane make-up, but unless you believe that he does in fact have the go-ahead from Our Lord Father in Heaven, Solomon Kane is every bit the murderer that Marvel’s Punisher is. Like Frank Castle, Solomon Kane just happens to be murdering scum. So in effect, the name of Solomon Kane represents “just murder,” or “just murderer.” He is the righteous wielder of God’s wrath, believing himself Heaven’s judge, jury, and executioner.

Delving deeper, it should be noted that despite his good intentions, Solomon Kane is a tortured soul. While we never learn the reasons behind his obsession, it’s clear that Solomon Kane views battling the evil in the world as his personal cross to bear. In his early stories, Solomon Kane is a man brimming with righteous maniacal energy, but through the years it becomes clear that the battles are taking a toll on him. His sanity is deteriorating in steady increments, and his journeys through Africa leave him questioning many assumptions about good, evil, and faith that seemed so clear to him in his younger days. He is also a wandering spirit at heart, making it impossible to rest.

In no place is his decaying frame of mind clearer than in the poem, “Solomon Kane’s Homecoming.” This piece about the Puritan adventurer was published a few months after Howard’s death. Chronologically, it can take place at any number of points in Kane’s life, but it has a feel of finality to it. There could have been more Conan tales or Kull tales written about later points in these characters’ lives, but this felt like a proper ending to the adventures of Solomon Kane. As to the poem itself, it’s a simple and haunting thing. After years of adventure, Solomon Kane returns home, wanting nothing more than to rest. But the restlessness gripping his mind and soul refuse to leave him be, and so that very same evening he leaves, journeying to parts unknown. His work is not done, even though the submerged rational part of his psyche wishes to kick back and relax.

These facets alone depict Solomon Kane as a far more complex and rounded character than either Conan or Kull. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of Solomon Kane are his inner struggles with racism. In many of Kane’s early adventures in Africa, he thinks of the natives as nothing more than savages and the descriptions of them reflect a rather racist attitude. Yet as time goes on, in various stories we see Solomon Kane learning to work with these natives, defend them, avenge their deaths, and in one story, attempt to free them from slavery. There is a transformation taking place in Kane as he learns the world is not as black and white as he first believed (pun honestly not intended!) and it leads to him becoming a better person without even realizing it. Considering Howard’s views toward black people, it’s very interesting that he would be willing to take his protagonist in this direction. Perhaps Howard recognized his own shortcomings on matters of race, and Solomon Kane’s transformation was the closest Howard could come to a catharsis on this matter. It’s certainly not the first time Howard dabbled with matters of race, as his Kull story, “The Shadow Kingdom,” dealt heavily with overcoming one’s racial prejudices (and the characters succeeded).

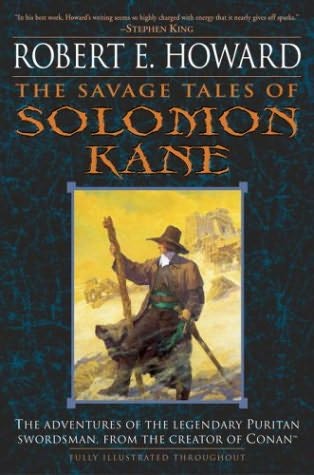

If you’re interested in reading about the adventures of Solomon Kane, Del Rey has released a comprehensive volume of Howard’s works concerning the Puritan adventurer called The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane. This book is part of the same series as those collecting Howard’s works about Conan & Kull. More than anything, these stories demonstrate that Howard was far from a one-trick pony when it came to sword & sorcery, as we’re introduced to a character of deep complexities. In Conan, Howard created an archetype and icon. In Kull, he provided us a thinking man’s barbarian, battling the stereotype that has pervaded this sub-genre for decades. And in Solomon Kane, we are given something equally important to the literature of sword & sorcery: a complex protagonist, along with successful sword & sorcery tales that don’t rely upon a barbarian protagonist.