One question that came out of John Scalzi’s apt blog post “Straight, White, Male: The Easiest Difficulty Level There Is” is this one:

“How might we understand the idea of class through video games?”

That is, if using the analogy of an RPG video game can help white male nerds understand institutionalized racism and white privilege, it’s also possible that video games might help nerds of every gender and race understand the concept of class structure and class struggle.

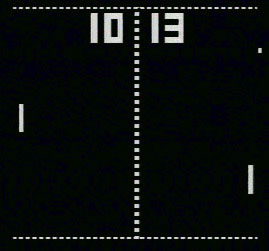

In Adam Curtis’s documentary “All Watched Over by Machine’s of Loving Grace” the filmmaker interviewed Loren Carpenter about his 1991 experiment using the game Pong to inspire mass collaboration. In the interview Carpenter explains how a group of 5000 people spontaneously figured out how to collaborate to play pong on a giant screen. The collaborating crowd spontaneously figured out how to cooperate with a minimum amount of communication and no hierarchal structures of power; there were no overt directions nor any chain of command, but the crowd was able to figure out how to collectively move the paddles on the big screen and keep the ball bouncing back and forth. They learned how to run a flight simulator game collectively, and how to solve the variety of other puzzles put to them. They worked together each time in a completely egalitarian way and as a mass.

Carpenter viewed his experiment as a demonstration of the possibility of radical democracy. The group mind was made up of 5000 equal players, each person worked freely, outside of the usual authoritarian modes. However, another way to view the same experiment would be from the opposite perspective. Rather than a demonstration of the efficacy of democratic participation it demonstrated the efficiency of a dictatorship. After all, while the 5000 individuals appeared to move as free individuals, it was Carpenter who determined the context and meaning of their movements. What Carpenter did was establish a very strong power relation, one that was so persuasive that it became almost invisible, and in this way he could direct 5000 people’s actions without having to bother giving 5000 separate commands or monitoring his worker’s actions.

Carpenter viewed his experiment as a demonstration of the possibility of radical democracy. The group mind was made up of 5000 equal players, each person worked freely, outside of the usual authoritarian modes. However, another way to view the same experiment would be from the opposite perspective. Rather than a demonstration of the efficacy of democratic participation it demonstrated the efficiency of a dictatorship. After all, while the 5000 individuals appeared to move as free individuals, it was Carpenter who determined the context and meaning of their movements. What Carpenter did was establish a very strong power relation, one that was so persuasive that it became almost invisible, and in this way he could direct 5000 people’s actions without having to bother giving 5000 separate commands or monitoring his worker’s actions.

In Carpenter’s experiment the class relation or power relation was realized in the game of Pong. In Carpenter’s experiment class was a video game.

“Language is a virus from outer space”—William S. Burroughs

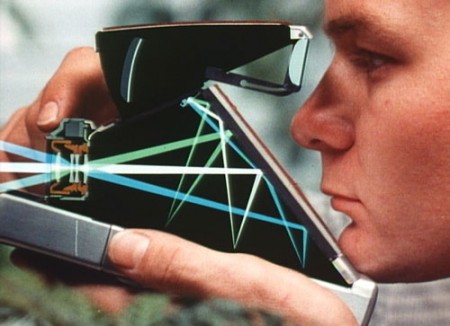

The same year as Carpenter’s experiment, CBS aired an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation entitled “The Game.” In this episode, William Riker was introduced to a video game while visiting Risa (the pleasure planet)

The same year as Carpenter’s experiment, CBS aired an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation entitled “The Game.” In this episode, William Riker was introduced to a video game while visiting Risa (the pleasure planet)

The game is a headset like the Kind rebel fighters wore in Star Wars, or the kind telemarketers wear today, only instead of ear phones this headset projected a holographic screen across the player’s field of vision. And it was on this screen that the game was played. It was a bit like a holographic version of a whack a mole game, only instead of moles, funnels emerged from the rows of holes on the bottom of the screen. The aim of the game was to move a frisbee into the writhing maws of the striped funnels that emerged from the holes. It was a game of virtual penetration, but in the game the vagina dentatas were phallic. The headset stimulated the pleasure centers in the player’s brain each time a frisbee entered a funnel, and we learned pretty early on that this game was a mind control device.

WESLEY: Correct me if I’m wrong, but this looks like a psychotropic reaction.

ROBIN: Are you saying you think the game’s addictive?

WESLEY: What’s going on in the prefrontal cortex?

ROBIN: Doesn’t that area control higher reasoning?

This game on Star Trek was an elaborate ruse. The product of alien technology, the game was designed to make the crew of the Enterprise suggestible and, eventually, designed to be used to maintain control over the entire Federation. This addictive game was a trap specifically planted on Riker in order to put the Enterprise to use in an alien conspiracy and expansion project.

The Game on Star Trek worked in mostly the same way as Carpenter’s version of Pong, but while Carpenter saw his game as benign or even invisible, the writer Brannon Braga depicted the game as an alien conspiracy.

The misunderstanding or mistake that Carpenter and Braga both make is to assume that there is an authentic way for people to operate in the world together, but while Carpenter imagines that he has demonstrated that people can be directly networked as equals without any mediating power, on Star Trek the appearance of the Game suggests that the usual interactions on the Enterprise are natural or endemic to the people of the Enterprise, that there is nothing foreign about the system the crew usually finds itself enmeshed in, and that any visible system of control or video game would have to be alien.

A 1972 a documentary advertisement or promotional film for Eastman Kodak and polaroid mentions the goal of both Star Trek and Carpenter.

“Since 1942 Edward Lamb and Polaroid have pursued a single concept, one single thread, the removal of the barrier between the photographer and his subject.” This idea that a photograph could be taken without “any barriers between the photographer and his subject” is the same goal that Carpenter aimed at producing for the entire mass of 5000 equals, and its the object that Wesley Crusher worked to reestablish on the Enterprise.

“Since 1942 Edward Lamb and Polaroid have pursued a single concept, one single thread, the removal of the barrier between the photographer and his subject.” This idea that a photograph could be taken without “any barriers between the photographer and his subject” is the same goal that Carpenter aimed at producing for the entire mass of 5000 equals, and its the object that Wesley Crusher worked to reestablish on the Enterprise.

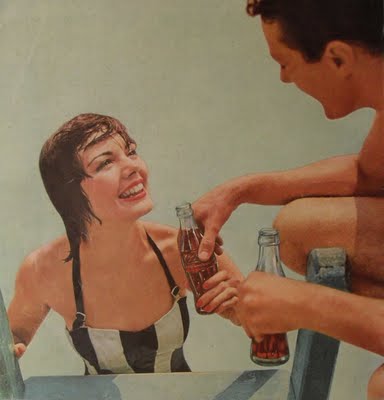

The goal is to find simple, authentic, and direct reality. What we’re seeking is something whole or complete. What we want is a social harmony, even as we live in a world where any idea about “the real thing” is as likely to evoke the ancient memory of an advertisement for a soda pop as anything solid or necessary. (In 1969 the Coca-Cola corporation replaced its “Things Go Better With Coke” campaign with the slogan “It’s the Real Thing,” and since then, the real thing has been associated with soda pop. In a way, reality was replaced by sugar water.)

What we want is something solid and real, but we find this is slipping away from us. Worse, most of our tried and true methods of maintaining some kind of authenticity just don’t work anymore. For example, Aram Sinnreich argued that the very idea of authenticity has to be reconceived in music today because of digital technology. In Sinnreich’s book Mashed Up he explains that his own clinging to authenticity, his love of acoustic guitars and other traditional instruments, as something that sprang out of an ideology of individualism and, ultimately, as something reactionary. He had to get beyond his love of traditional music if he hoped to progress with the digital advances of his day rather than react against them.

What we want is something solid and real, but we find this is slipping away from us. Worse, most of our tried and true methods of maintaining some kind of authenticity just don’t work anymore. For example, Aram Sinnreich argued that the very idea of authenticity has to be reconceived in music today because of digital technology. In Sinnreich’s book Mashed Up he explains that his own clinging to authenticity, his love of acoustic guitars and other traditional instruments, as something that sprang out of an ideology of individualism and, ultimately, as something reactionary. He had to get beyond his love of traditional music if he hoped to progress with the digital advances of his day rather than react against them.

However, Sinnreich’s attempt to get beyond authenticity by moving beyond the usual framework for “modern discursive practice” he describes as a series of binaries:

“Art as opposed to craft. Artist as opposed to audience. Original as opposed to copy. Etc…”

Sinnreich proposed that the way to move beyond these binaries was precisely to erase or remove the barrier between one side and another, and McKenzie Wark said something similar in his 2007 book Gamer Theory. He wrote that today’s “Gamespace needs theorists but it also needs a new kind of practice. A practice that can break down the line that divides gamer from designer.”

But, this attempt to erase the line or the demarcation between two binary terms is the same move that Polaroid states as it’s singular goal. It is just another way to treat Pong as if Pong is invisible and it’s just another way to blame the aliens for what goes on aboard the Enterprise.

The line between an artist and her audience is both a barrier and a bridge. In the same way, even this game we’re playing now as the Mayan calendar turns over and the world sits on the brink of a second round of economic panic, even this game called class structure or class struggle, is nothing other than the currently necessary ideological screen that makes our social and productive lives possible.

The line between an artist and her audience is both a barrier and a bridge. In the same way, even this game we’re playing now as the Mayan calendar turns over and the world sits on the brink of a second round of economic panic, even this game called class structure or class struggle, is nothing other than the currently necessary ideological screen that makes our social and productive lives possible.

Douglas Lain is a fiction writer, a “pop philosopher” for the popular blog Thought Catalog, and the podcaster behind the Diet Soap Podcast. His most recent book, a novella entitled “Wave of Mutilation,” was published by Fantastic Planet Press (an imprint of Eraserhead) in October of 2011, and his first novel, entitled “Billy Moon: 1968” is due out from Tor Books in 2013. You can find him on Facebook and Twitter.