Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

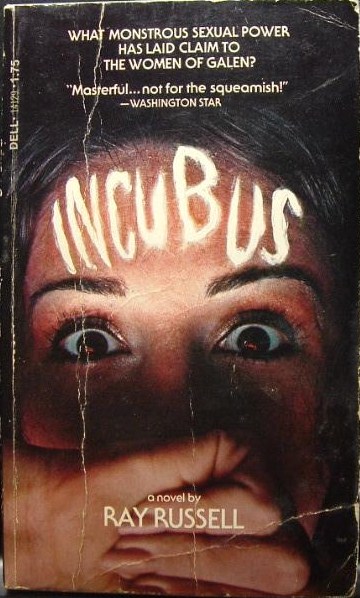

Here we’ve reached the Summer of Sleaze’s final chapter, mere days before the beginning of autumn. For this last part I present one of my sleazier favorites of the 1970s, a bit of salaciousness called Incubus, first published in hardcover in 1976—yes, hardcover! Fancy.

Author Ray Russell (b. Chicago, 1929; d. LA, 1999) may not be a familiar name to you, but opens in a new window![]() you’ll appreciate his credentials: as an editor and contributor to Playboy magazine from the 1950s to the late 1970s, he brought to that esteemed publication authors like Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, as well as the writings of one Charles Beaumont, the all-too-soon-late scribe who contributed so much to the horror genre, most notably through episodes of “The Twilight Zone” and screenplays for some of those Roger Corman Poe flicks from the ’60s.

you’ll appreciate his credentials: as an editor and contributor to Playboy magazine from the 1950s to the late 1970s, he brought to that esteemed publication authors like Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, as well as the writings of one Charles Beaumont, the all-too-soon-late scribe who contributed so much to the horror genre, most notably through episodes of “The Twilight Zone” and screenplays for some of those Roger Corman Poe flicks from the ’60s.

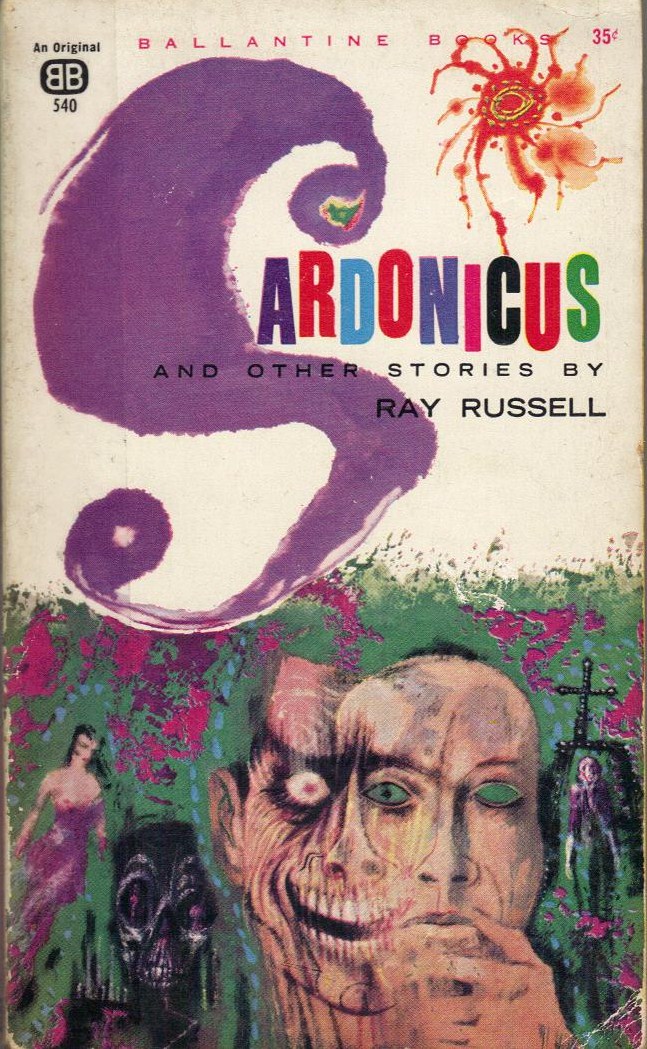

Russell, like his pal Hugh Hefner, was a longtime fan of macabre fiction, and turned his hand to it in classic novellas of Gothic Grand Guignol like “Sardonicus” and “Sagittarius.” But it is Incubus that I feel reaches heights—or depths—of delightfully tacky horror fiction, a perfect example of sleaziness presented in a prose style honed by years of professional writing and editing experience. Ready for Incubus? Because it’s ready for you…

In the seaside California town of Galen, young women are being raped and killed. Their bodies are left ripped and torn, leading some to think the perpetrator is not wholly human. The authorities are at a loss. Enter Julian Trask, well-known esoteric anthropologist who once taught in the town and returns because he has a terrifying theory about the killer: that what is driving the deranged individual is not power, but procreation. Thing is, the procreation part isn’t working out because the killer rapist is, shall we say, well-endowed. Outrageously so. Let’s just say it: its member is so huge it can’t impregnate, it can only kill. There. It’s not human, so what is it? An incubus, Trask tells ol’ Doc Jenkins, a Scotch-swilling small-town doctor whose agnosticism won’t let him reject Trask’s theory out of hand.

The main suspect is teenaged Tim Galen, who lives with his old Aunt Agatha in a creepy old house. They’re the last of the Galen clan who settled the town, but there is some shadiness in Tim’s past, as Auntie hated his late mother, the woman who married Agatha’s beloved brother, and who suggests her ancestors had been witches burnt at the stake. So of course, Tim might have tainted blood. But he doesn’t have any kind of memory of doing these horrible things… until he begins having dreams of a woman accused of being a witch tortured on the rack, in the Middle Ages. Is his ancestral blood coming to the fore? Could it really be him—? This horrifies him and so he reaches out to Julian for help. Insert “catch-the-killer-before-it’s-too-late” scenario here, because no Galen woman is safe…

More and more women are attacked in gruesome yet quite competently written scenes of sexualized violence. What makes these readable, for me at least, is that they don’t carry the skeevy, sinister air of voyeurism that some later horror writers allowed to seep into their prose describing the same sort of thing; Russell doesn’t write like he’s secretly getting off on his scenarios. Sure, they’re tasteless and unsettling, but that’s par for the horror course.

Those Middle Ages torture interstices rival anything the later splatterpunks would produce—perverse goings-on that would satisfy Bataille, de Sade, Krafft-Ebing. I dig the appearance of an ancient grimoire that speaks of “dawn gods, creatures older than the human race.” Even a thoughtful moment or two turns up as Julian and Doc Jenkins debate supernaturalism, agnosticism, skepticism, and whatnot. (And I really liked Doc Jenkins; every time after a crisis he suggested everyone join him at his home or his office to discuss the disturbing events over ample tumblers of whiskey). Incubus is definitely a page-turner, and while the climax seemed to strain credibility, Russell’s skills are in top form.

The sexual politics, if you will, of Incubus are a real window into the past. Sometimes I couldn’t tell if Russell was satirizing traditional sex roles or, like Playboy felt it was doing back in the day, embracing a newfound freedom with open fervor and celebrating a healthy lust for, uh, life in both men and women. Was Russell being sexy or sexist? Throughout the novel are moments in which it becomes clear that Russell had spent formative years as Playboy’s fiction editor: there’s an open-minded attitude about sexual relations between consenting adults; the older generation thinks something as common as a blow job is filthy, vile, and depraved; women are depicted as having a sex drive comparable to men and are able to express it on their own terms. Science and rationality are the tools of the day, even when dealing with old world monsters.

This attitude, while commendable, still has a contradictory whiff of old-fashioned chauvinism (no surprise John Cassavetes starred in the 1981 movie adaptation; Cassavetes, genius or misogynist?!). Male characters casually allude to women’s physical appearances, even when that woman is a teenage daughter of a male friend; female characters are sometimes described as if they are potential Playboy Playmates—you know Stephen King would never note a woman’s small but perfect breasts or her high cheekbones, much less her “fleecy down” (to be fair, Russell also notes the hero’s “square jaw” and “ebony thicket”!).

Then there’s the rationalist, intellectual, agnostic approach taken by two main characters: it is meant to be seen as modern and au courant, but kind of comes off as arrogant and privileged. There’s an unfortunate breeziness about sexual assault, too, by men and women alike, as if some men are too horny for their own good and have to sometimes take it by force. But still, everyone in the novel is horrified by what’s happening and only crazy old Aunt Agatha, the real human enemy, thinks these women got what they deserved.

But the attempt to normalize the sexual natures of adults, to get them to be seen as healthy and essential, is prominent; that’s the way many of the characters talk, a bit of the ol’ ’60s Playboy philosophy wrapped inside a lurid tale of the macabre (this technique is also on full display in Russell’s superb novella of Gothic horror, “Sardonicus”). I don’t know if this is visible to readers who don’t know Russell’s background; for me, it felt like Russell was psychoanalyzing himself, projecting his own personal identity and beliefs and peccadilloes onto a horror story.

Maybe it was just me, but I felt these opens in a new window![]() concerns swirling beneath the sleazy surface. Mostly all this made me smile wryly to myself, this incongruous philosophizing about “modern” mores and how dated it seems in the 21st century. But that is one reason why I love reading this kind of popular fiction from the past! Whether you take the novel at face value or detect an ironic, knowing tone, Incubus is prime ’70s horror fiction ripe for rediscovery.

concerns swirling beneath the sleazy surface. Mostly all this made me smile wryly to myself, this incongruous philosophizing about “modern” mores and how dated it seems in the 21st century. But that is one reason why I love reading this kind of popular fiction from the past! Whether you take the novel at face value or detect an ironic, knowing tone, Incubus is prime ’70s horror fiction ripe for rediscovery.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.