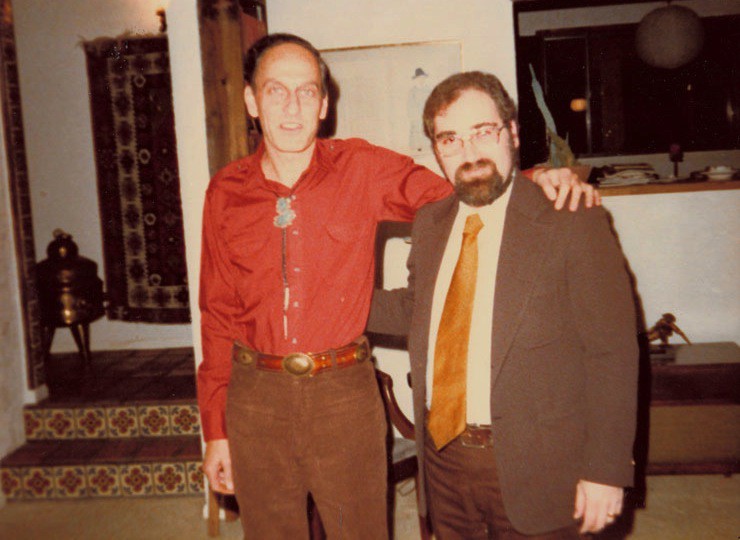

On a crisp November morning in 1982, I stood on a mountain beside a modest two-story home outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico. I heard a car coming up the winding dirt drive from below. Gravel and dust kicked up as the car climbed up and pulled in alongside mine.

Tall and slender, the driver ambled over to me, a smile on his face. “Ted Krulik?” he asked, holding out his hand.

“Yes,” I answered. “Mr. Zelazny? It’s good to meet you.”

“Glad to meet you. Call me Roger.”

That was the beginning of my friendship with Nebula and Hugo-award winning author Roger Zelazny. He had allowed me into his home that November day to conduct a week-long series of interviews for Roger Zelazny, the literary biography I was writing for Frederick Ungar Publishers in New York. My interviews with him at his home and in later interviews over the next ten years were much more than simple Q&A. Roger didn’t stop at a brief statement to anything I asked. He responded with deep insights that revealed experiences and perspectives that he rarely talked about anywhere else.

I still listen to Roger’s voice expounding on the questions I asked him. They’re on recordings and videos I made of those interviews. He’s alive to me, his soft rasping voice and sparkling eyes searching inwardly, in my living room. He told me stories about his childhood, his family, the other writers he came to know, his sources of inspiration, and what he hoped to accomplish in the future. I want to share those stories with you. Here are some of them…

Balancing Fantasy and Science Fiction

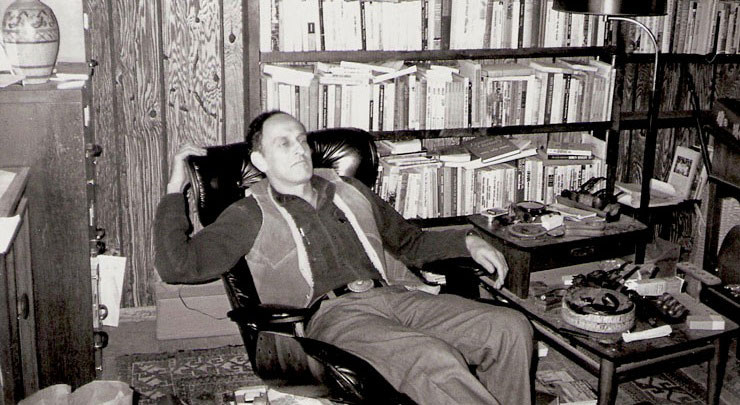

Known for such fantasy novels as The Chronicles of Amber and The Changing Land, Roger was equally adept at writing works using the elements of science fiction, novels like My Name Is Legion and Damnation Alley. I asked him: Which is easier to write, fantasy or science fiction? He sat comfortably back in his easy chair in the lower level of his home and gave the following answer:

I find fantasy easier to write. If I’m going to write science fiction, I spend a lot more time thinking up justifications. I can write fantasy without thinking as much. I like to balance things out: a certain amount of fantasy and a certain amount of science fiction.

In a sense, fantasy is a freer play of the imagination. You can achieve exactly the situation you want with less groundwork, less of a need to fill-in all of the background.

For science fiction, I would use a lot of sources to set up, for instance, what a being from another planet would be like.

I suppose if I wanted to create an alien being in fantasy, the creature could be a golem created by, say, four sorcerers. I wouldn’t have to go into a long explanation as to the nature of the creature.

I could explore the same sort of ideas in either science fiction or fantasy, but with fantasy, it’s easier to deal with the gimmicks. On the other hand, many of the things I want to explore have more application to the real world. The kind of society I like to deal with is not much different from our own. If I were concerned with a particular social issue, a fantasy story might not be right for it. Some of my concerns lend themselves more to one genre than the other. When an idea occurs to me, I know immediately which type of story it’s going to fit into.

—Santa Fe, NM, 1982

Years later when this topic came up again, I asked, “Do you want to hold onto a science fictional quality within your fantasy novels?”

Roger’s reply:

I see. You’re asking: how much of a rationalist am I? I do tend to find ways of justifying my fantasy. If there is some transformation – if matter isn’t actually entirely disappearing – there is going to be some indication that matter isn’t destroyed. It’s being turned to energy and broadcast somewhere – so that the ground may suddenly be hotter as a result.

I don’t just throw in the wonders and not explain them. At least in my own mind I have to work out how it could be. That’s just the way I look at things.

—Lunacon, Tarrytown, NY, 1989

Larger Than Life

In Roger’s writing, his protagonist is often someone who is long-lived, self-assured, and cultured; someone who faces imminent danger with a wisecrack. I wondered why he liked exploring that type of character so frequently. Here is his answer:

If one has an extended lifespan and has lived as long as the characters in Lord of Light, one would need to have a sense of humor. I think it was Pasqual who said, “Life is a tragedy to the man who feels, and a comedy to the man who thinks.” My characters think more just by virtue of having more time in which to do it.

That’s one thing I like about the Elizabethan dramatists, like Shakespeare. No matter how serious a scene is, the playwright always had time to slip in a pun.

I am fascinated, I suppose, by a flawed man with a streak of greatness. I am not unsympathetic to less savory characters. I care more, and I think readers do also, for characters in a state of transformation. It would be wrong to write a book where the protagonist proceeds through all the events of a story and winds up pretty much the same at the end. What happens to him shouldn’t be just an adventure without having any effect on him. He has to be changed by the things that take place.

Gallinger in “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” was a version of something Mallory once talked about: to get a very strong character you make him highly neurotic or compulsive and put him in a situation which frustrates him to see what he would do. If he’s resourceful, he’ll find an answer or some way that either strengthens him or breaks him.

So I wanted a character who was not just a normal person. I gave him great talents but I also gave him emotional weaknesses. For “A Rose for Ecclesiastes,” I didn’t just want to write a space opera rehash. I was interested in writing a character study.

Perhaps there is a fine line between pushing a character to the extreme and crossing over into parody or satire. If you play with extremes of characterization, you run into something like that, where quite often an extreme of nobility or an extreme of genius can become something close to ridiculous.

I like a character that is complex. I don’t like writing about people who are simple-minded or average. Any protagonist I write has to be somewhat complicated. I can see that readers might see him as a bit larger-than-life, but that’s not my intention. My intention is to examine the psychological, emotional, and mental changes in a complicated man, a man of greatness.

—Santa Fe, NM, 1982

Some Ideas George Gave Me

Writers work on their writing in very individual ways. I asked Roger what a typical writing day was for him. This is what he told me:

When I’m beginning work on a book, I’m happy to write something every day. It doesn’t matter how much. At the half-way point, I’m usually turning out about 1500 words a day. I tend to write a little more slowly, but the copy I produce doesn’t require much work once it’s finished.

When things do begin to go very well with a book and I’m getting near the end, I’ll write in the evenings and at any odd moment during the day. I move faster as I get nearer the end, so that I produce large amounts of copy in a day’s time. I may turn out three or four thousand words a day. There’s a point where it just begins to flow, usually in the latter stages of the book. If my writing gets going like that earlier in the writing, I’m usually working on a scene that I’m particularly fond of, something that I’m enjoying.

I had been working on a project with another science fiction writer in New Mexico, George R. R. Martin. George gave me some papers on the project to look over. Shannon [Roger’s daughter, age six at the time] came over while I was working and asked me what I was looking at. I said, “These are some ideas George has given me.”

Sometime later, a local newspaper reporter asked Shannon if she knew where I got my ideas. She answered, “George R. R. Martin gives them to him.”

—Necronomicon, Tampa, FL, 1985

Discover additional posts on Ted Krulik’s interviews with Roger Zelazny.

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.