In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The authors of the Golden Age of science fiction, and their works in later years, were indelibly shaped by World War II. Many served in the Armed Forces, while others worked in laboratories or other support functions—Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and L. Sprague de Camp, for example, worked together at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Time passed, and in the 1970s a novel appeared, The Forever War, which was written by newcomer Joe Haldeman, a member of a new generation who was shaped by a very different war. The book, with its bleak assessment of the military and warfare in general, had a profound impact on the field. And today, as more and more people refer to our current conflict with terrorists as the Forever War, the book’s viewpoint is as relevant as ever.

Regarding writing, Samuel L. Clemens is quoted as saying, “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—’tis the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.” If you put together enough of the right words, in all the right places, you can produce a novel that has the impact of a lightning bolt. That is exactly the impact The Forever War had on me. I was in my third year at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, and bewildered by the social changes I was seeing in the country around me. I had joined up in the waning days of the Vietnam War, and even though they were no longer drafting people, I still remember my draft number being picked. We had all watched the helicopters carrying our embassy staff out of Saigon, our last involvement in a demoralizing conflict. To go out in public in a uniform, or even with just a military haircut, could draw insults like “fascist” and “babykiller.”

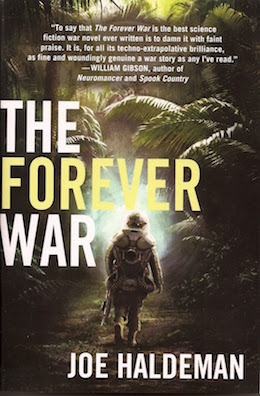

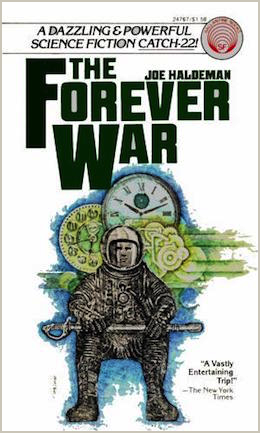

To many people, serving in the military was no longer an honorable profession. The gung-ho military adventures I had read in my youth had not prepared me for this. But I still had an interest in military science fiction, so when I saw a paperback edition of The Forever War in a local bookstore, I snapped it up. It had a man in a spacesuit on the cover, surrounded by old timepieces and with a saber across his lap (at the time, I thought the sword was as symbolic as the clocks, not realizing it would play a role in the tale). I remember reading it in large gulps, and feeling throughout that this Haldeman guy really knew what he was talking about. And I was not alone. The book sold very well, was critically acclaimed, and won both the Nebula and Hugo awards.

Background: The Vietnam War

War came to Vietnam in World War II and continued in the wake of that conflict, as the local population revolted against French colonial rule. The French withdrew, leaving the nation split between NATO-supported South Vietnam, and communist Russian and Chinese-supported North Vietnam. U.S. involvement in the war between North and South Vietnam began in the 1950s but escalated significantly in the 1960s, with advisors and military aid giving way to regular troops, and significant air and naval campaigns. The draft was re-instituted to meet demands for troops.

At the same time as the war effort was ramping up, the U.S. found itself in a time of internal turmoil and spiritual re-awakening. The younger generation was questioning old truths, and experimenting with drugs and alternative religions and philosophies. The draft was a polarizing force in society, and many people, especially younger people, turned against the war, and the military in general. This made the homecoming of veterans very difficult, as they were already demoralized by their service in a bloody and difficult struggle, and were often treated with derision and contempt upon returning to the U.S.

U.S. involvement in the war peaked in 1968, around the same time as the North and the Viet Cong insurgents launched the Tet Offensive. While inconclusive militarily, the widespread attacks undercut Department of Defense arguments that the U.S. had been successful in destroying the enemy’s military capabilities, and support for the war among the American public dropped significantly. A peace treaty was signed in January 1973, and U.S. military involvement ended in August 1973. Saigon was captured by the North Vietnamese Army in April 1975, and the evacuation of the U.S. embassy marked the ignominious end of a divisive conflict.

About the Author

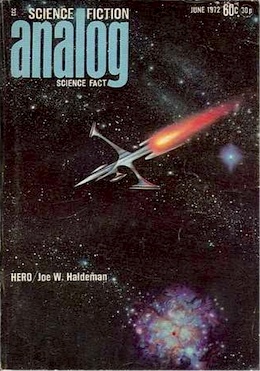

Joe Haldeman (born 1943) graduated from the University of Maryland with a BS in astronomy in 1967. Shortly after that, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and despite personal concerns about the morality of war, he served from 1968-9 as a combat engineer in Vietnam’s central highlands. Wounded in an incident involving unexploded ordnance, he returned home with a Purple Heart. He had always wanted to be a writer, and received early encouragement from Damon Knight’s Milford Writer’s Workshop, and specifically from Ben Bova, who was also in attendance. Bova had encouraged Haldeman to write fiction based on his wartime experience, which led first to a mainstream novel, War Year, and then to the science fiction novel The Forever War. When he succeeded John Campbell as editor of Analog Science Fiction, Bova purchased the story, and it appeared in four Analog installments from 1972 to 1975, and was published as a standalone novel in 1975.

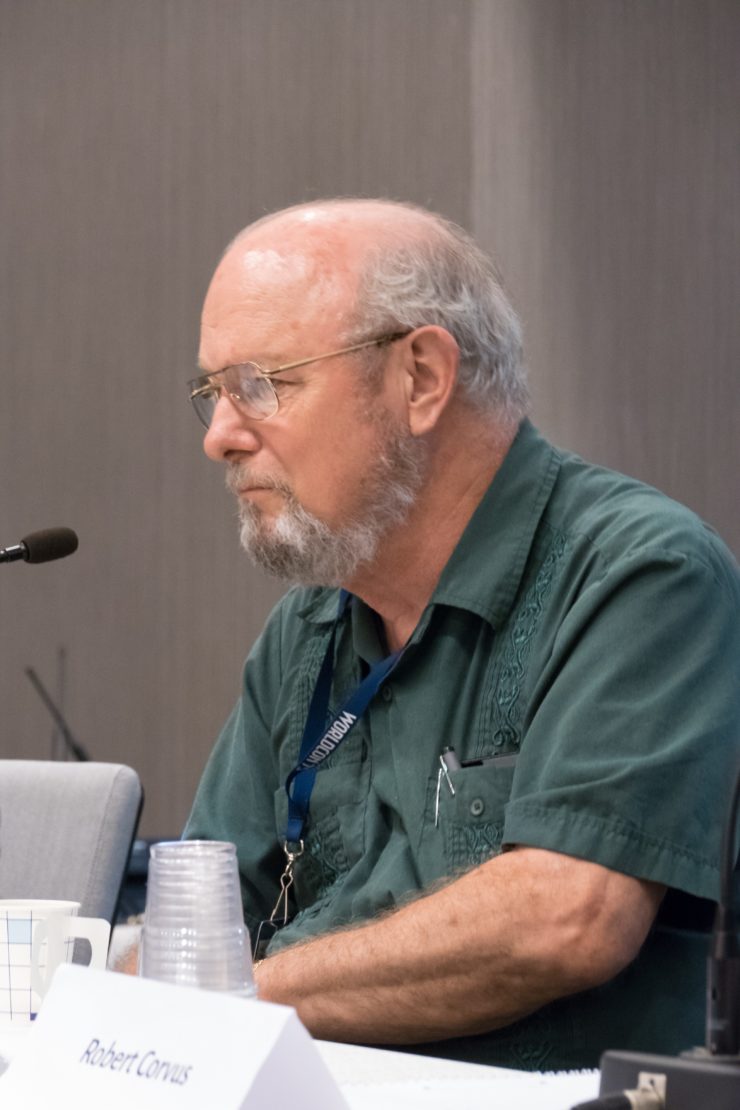

The Forever War, besides winning both the aforementioned Hugo and Nebula awards, started a long and distinguished career for Joe Haldemen. He went on to win six more Hugos and four further Nebula awards for later novels, novellas, and short stories. He was elected a SFWA Grand Master and a member of the SF Hall of Fame. Haldeman is a consummate professional, whose focus is writing what he is passionate about, rather than simply to earn money. He is a fan of Ernest Hemingway, and it shows in his prose, which is crisp and carefully crafted. By all accounts he is generous to his fellow writers, and I know from personal experience that he is generous to fans, as is his wife Gay. At my father’s insistence, my introduction to fandom and WorldCon was a “How to Attend a Con” panel co-hosted by Gay and long-time fan Rusty Hevelin, and I remember interactions with Joe as highlights of an event that was packed with special moments.

The Forever War

The book starts in 1997, following the military career of William Mandella, a child of hippie parents who has been drafted under the Elite Conscription Act. The human race has discovered that links between collapsars are the key to long range travel around the galaxy, but mankind soon encounters a mysterious race they call the Taurans, ships are lost, and a punitive expedition is planned. The personnel picked for the United Nations Exploratory Force (UNEF) are not only sound of mind and body, but all have IQs of at least 150. The force mixes men and women, encourages sex between them, allows the use of marijuana, and considers “Fuck you, sir” as the appropriate response to an order to come to attention. Because of the distance of travel to get to collapsars, even at relativistic speeds, missions will be measured in months, if not years—and that is the objective time experienced by the travelers. Back home, because of relativity, the length of the missions will be measured in years and decades.

The book starts in 1997, following the military career of William Mandella, a child of hippie parents who has been drafted under the Elite Conscription Act. The human race has discovered that links between collapsars are the key to long range travel around the galaxy, but mankind soon encounters a mysterious race they call the Taurans, ships are lost, and a punitive expedition is planned. The personnel picked for the United Nations Exploratory Force (UNEF) are not only sound of mind and body, but all have IQs of at least 150. The force mixes men and women, encourages sex between them, allows the use of marijuana, and considers “Fuck you, sir” as the appropriate response to an order to come to attention. Because of the distance of travel to get to collapsars, even at relativistic speeds, missions will be measured in months, if not years—and that is the objective time experienced by the travelers. Back home, because of relativity, the length of the missions will be measured in years and decades.

The UNEF has decided that bases are needed on planets around the collapsars, to defend against enemy incursions; because these planets will be cold, the troops are trained out on Pluto and beyond, where the environment is more dangerous than enemy action. They are trained to operate in powered armor suits, to build bases and weapon systems, and in personal combat, should that be required. Despite his misgivings about the military, Mandella has a knack for leadership, and soon finds himself promoted to corporal. He also finds himself developing a friendship with fellow trooper Marygay Potter.

Their training for operations in extreme cold turns out to be premature, as their first mission takes place under different conditions. They are sent to attack an existing enemy base on a planet near the Aleph Aurigae collapsar. Since that collapsar orbits around the star Epsilon Aurigae, the conditions they fight in will be more in the range of those found on Earth. Approaching their destination on the ship Earth’s Hope at two gravities of acceleration, the troopers destroy both an enemy vessel and the missile it launched against them. On the march to the enemy base, they notice the planet’s odd ecology, and soon find their force shadowed by alien creatures. They kill and dissect them, and from the contents of their stomachs, find that they are local herbivores.

One of the soldiers dies of a massive cerebral hemorrhage, and it seems that the bear-like creatures use some sort of telepathic communication. They see a Tauran flying by in a bubble-like craft, a creature with two arms and two legs, but otherwise not human in appearance at all. When they have the enemy base surrounded, their sergeant quotes lines of poetry that trigger post-hypnotic suggestion, and the team destroys the base and butchers its inhabitants. In the end, though, more troopers are hurt by the psychological impact of the post-hypnotic suggestion than the enemy, and one of the enemy escapes in a ship to bring word of what has happened to the Taurans.

The team then finds themselves sent on the ship Anniversary to another campaign near the collapsar Yod-4. Mandella is now a sergeant, and Potter a corporal, and their relationship has grown closer. While they have experienced only two subjective years aboard ship, over two decades have elapsed for the rest of the universe, and technology on both sides of the conflict is advancing in leaps and bounds. The Taurans are pursuing their ship, and the team retreats to newly developed acceleration shells, designed to protect them while this more advanced ship accelerates at up to 25 gravities. They find that the enemy now has drones that accelerate at over 200 gravities, and they retreat to their acceleration shells for evasive action. Potter’s acceleration shell fails, and she is badly injured and near death. Their ship has been damaged, destroying their armored suits and killing many troops. They have no choice but to return to base, and the survivors are sent back to Earth.

At this point, different editions of the book vary significantly. The original version I purchased in 1976 focuses largely on Mandella and Potter’s experiences on a military public relations tour, as well as visiting his family. The Earth has not fared well in the years they have been gone; the population has grown significantly, to the extent that homosexuality is now actively encouraged as a population control measure. The Earth can barely feed its inhabitants, and getting enough to eat is a daily worry. Crime is rampant, and Mandella is horrified to find that medical resources are rationed—his mother is dying because she has not been approved for treatment. Disgusted with what they see, Mandella and Potter accept the military’s offer to return to duty with officer’s commissions. More recent editions of the book restore Haldeman’s original text, however, which depicts a much longer time on Earth, with a visit to Potter’s family showing the brutal conditions on a farm country commune. While this does stray from the military theme of the book, I find the longer interlude is more satisfying, as it not only deals with the alienation the troops experience upon returning home, but also provides a more convincing motive for the protagonists’ return to the horrors they have experienced in combat.

The book then covers Mandella and Potter’s service as lieutenants, a time of brutal and inconclusive struggles that ends with both in the hospital, wounded and with lost limbs. They think this will be the end of their military careers, but it turns out that limbs can now be regrown, something they hadn’t realized was possible. While time passed quickly for them due to time dilation, this period covers over three hundred years of objective time, and humanity and the military are becoming unrecognizable. Homosexuality has become the norm rather than the exception, and back on Earth there have been whole cycles of destruction and rebuilding. Even the language is different, and Mandella and Potter find they speak in an archaic dialect. They have no home to go to, the war continues on, and the powers-that-be are eager to capitalize on their knowledge as experienced combat officers. And in the interest of people who haven’t yet read the book, I will leave my summary here and the ending unspoiled, with encouragement to go out and find a copy.

The Forever War is carefully crafted and well researched. Haldeman’s training in astronomy is strongly in evidence, and consistent with the thinking in the field at the time the book was written. The conditions we expect to find in the extreme cold of outer planets are accurately described. The armored fighting suits are presented with capabilities that feel realistic. The spaceships and their maneuvers are portrayed in a scientific manner (although it always breaks my heart to read older books that assume capabilities for space travel would advance, rather than collapse at the end of the Apollo program). Medical scenes feel true to life, and the research that went into writing them is in clear evidence. The impact of relativity and time dilation is well developed, and has a huge impact on the plot. The characters feel real, and by the end of the book the reader will care about their fates. The prose is crisp, direct and rich with details, yet those details are presented organically, and they never bog down the narrative. This book is not only one of the best military science fiction books ever written, but is one of the finest works of modern American literature.

Final Thoughts

The Forever War is a modern classic. It presents an unflinching view of the horrors of war, and the corrosive effect war can have on a society. It deals with themes of loss and alienation that are often overlooked by other writers of military fiction, whose focus is bravery and glory. The U.S. military has been waging war on terrorists since the turn of the century. Like Mandella and Potter, we have veterans who have served in deployment after deployment, finding civil society increasingly disorienting each time they return. At a time when we are engaged in another type of Forever War, this book gives us a lot to think about.

The Forever War is a modern classic. It presents an unflinching view of the horrors of war, and the corrosive effect war can have on a society. It deals with themes of loss and alienation that are often overlooked by other writers of military fiction, whose focus is bravery and glory. The U.S. military has been waging war on terrorists since the turn of the century. Like Mandella and Potter, we have veterans who have served in deployment after deployment, finding civil society increasingly disorienting each time they return. At a time when we are engaged in another type of Forever War, this book gives us a lot to think about.

So if you haven’t read this lightning bolt of a book, go out and find a copy. And if you have read it, I’d like to hear from you. When did you first read it, and what was your reaction? How do you feel about the themes it presents, and the way those themes are handled? And have your responses to the novel changed at all, over time?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy

The Forever War is my favorite SF book. I still have my original copy (the lead photo for the article) and have read every edition that’s been released and even corresponded with Haldeman in the late 90s when I noticed a difference in the editions. Joe’s writing style influenced much of my own SF and for that I’m grateful. I couldn’t have learned from a better Master.

You already spoiled the biggest kick-in-the-gut in the book literally two sentences before the part I quoted. That is a HUGE spoiler to reveal so casually, and it robs new readers of the biggest emotional gut punch in the book. It’s like telling someone “Marion Crane dies halfway through Psycho, but I don’t want to spoil the ending for you.” Um…yeah…you already spoiled the bigger surprise.

I’d reconsider that entire paragraph if you actually care about new readers experiencing this novel fully.

While I appreciate references to The Who, in my mind The Forever War is inextricably linked with another classic 60’s song. (I’m listening to it as I read this.)

OTSOTA, we sat out Vietnam first time round and instead waited for the movie to come out, so I suppose I won’t get some of the visceral feelings someone closer to the conflict would experience. By the time I first read it, in the final version, parts of Haldeman’s future were my past. Nonetheless, a classic is a book relevant far beyond the time and place of its creation and it is in this regard that I recognise the scope of Haldeman’s triumph: his deployment of military science-fiction tropes gave me an understanding of a soldier’s internal conflict I hadn’t got from any other book and I am particularly grateful to him for that. (As an aside, I’m happy to hear of his generosity in real life.)

I have read elsewhere that, while Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage was another direct influence on The Forever War, it was also in part a “unconscious” response to Heinlein’s Starship Troopers; the contrast between the perspectives of conscripts and volunteers is certainly striking. (Gordon R. Dickson’s Naked to the Stars arguably does something similar.) Haldeman said that Heinlein came up to him after he received either the Hugo or the Nebula (I forget which) and told him that he had enjoyed The Forever War so much that he had already read it three times. (Strange to see an SF disagreement resolved in a civil and constructive way…)

ETA: Some pedantry: the original middle section of The Forever War, “You Can Never Go Back”, was published in Ted White’s Amazing as Bova thought it too downbeat for Analog. Before Haldeman added it back into the book in 1991, it was available in his collection Dealing in Futures.

I also have the original paperback and have reread it several times over the years, but I had no idea there were different editions. Time to hunt one up and read it again.

@2 PaulB You raised a good point, and the paragraph in question has been amended. I appreciate the feedback!

@3 SchuylerH Thanks for the additional info on that amended middle to the book. I was trying to remember the collection where I originally read that longer version, and you gave me the answer: Dealing in Futures. I have that book somewhere in my basement, but couldn’t find it while preparing this review.

@5: I also have Dealing in Futures; Haldeman’s longer, better explanation of what happened (from his introduction to “You Can Never Go Back”) follows:

“… The novella that follows was originally the middle section of my novel The Forever War. I like it better than the version that got into print.

The Forever War wound up being my most successful novel, sweeping the science fiction awards for 1976, and still going strong in its umpteenth printing. But it wasn’t an immediate success; it was turned down by eighteen publishers before St. Martin’s Press took a chance on it. Most of the publishers felt it was an okay story, but nobody wanted to buy a book that was so transparently a metaphor about Vietnam.

While the outline-plus-sample-chapters package was being rejected by all those publishers, I of course continued writing the book. It’s an episodic story, so I was able to sell the individual sections as more or less independent novellas. Analog magazine picked them up, and the editor, Ben Bova, was of immeasurable help, for moral support as well as canny storytelling advice. (In fact, it was Ben who convinced St. Martin’s, who did not at that time publish adult science fiction, to take a look at it.)

He sent this novella back, though, with grave misgivings. Most of The Forever War is set in outer space – where the war is – but most of this story takes place back on Earth. He felt that including it in the novel would slow it to a halt. Besides, the dystopian view of future America was too depressing.

Maybe he was right. After some thought I did set it aside, and wrote the shorter novelette “We Are Very Happy Here”, of which less than five pages takes place in the United States, and that’s what wound up in the book. It does move faster than it would have with this story, which is certainly a virtue in a novel of adventure. But I still like this one better as a story.”

@6 Thanks for that quote. It’s good background. And it’s good to give credit to Ben Bova, who played a big part in getting Joe Haldeman the attention he deserved. In my opinion, Bova is second only to Campbell as the best of all the editors of Analog. Come to think of it, a Bova book should probably end up in this review column sometime in the coming months (and there are so many good ones to choose from)!

I first came in contact with The Forever War through a (french-style) graphic novel adaptation, made, IIRC, by Marvano. That was, I believe, in the early 90’s. In fact, at the time I did not know there was also a novel that it was based on; I read the novel some years later, maybe around the year 2000. I greatly enjoyed both versions (but then, I did not re-read the graphic novel version after reading the novel – maybe I would have been frustrated).

My memory may be playing tricks, but I believe the graphic novel did not include the longer back-to-earth episode. It may have been faithful to the shorter novel verion, though.

I don’t know whether an English-language translation of the graphic novel exists, but if one does, or if you can read French, I also highly recommend it. I believe it was originally published by Aire Libre, in 2 or 3 large format books.

@5 – Thanks for making the change! And sorry for my aggressive tone. I just reread my comment, and that last sentence is just jerk-ish. Sorry ’bout that! :)

@7: I have some vague memories of a couple of Bova’s early books but I mainly know of him through his tenure at Analog. I would be interested to hear how some of his own fiction holds up.

@8: Looks like it got an English-language reprint. Apparently, Haldeman worked closely with Marvano on the adaptation and it is faithful to the original edit of the novel.

The Forever War is classic. I stumbled on it in a used book store and picked it up looking for some new science fiction to read. I think I read it in one session. Really great hard sci-fi. I read Forever Free, and that was good, but man what a different shift from the previous story.

On a Halderman kick after that, I went looking for other works of his, and found the sadly out of print All My Sins Remembered. Aside from it being a great title cribbing from Hamlet, and great cover art, it turned out to be another wonderful read.

Starts off as kind of a James Bond sci-fi spy action novel, again very episodic, and ends with a melancholy meditation on the cost of duty, and the value of a human life. I think it probably doesn’t have the same support that The Forever War does because the ending ends up being kind of abrupt and a little less subtle in it’s themes. Still, a great read, and if you can find a copy, I encourage everyone to read it.

A Separate Peace is a very decent companion story. Not imprescindible, but nice to read as a coda after Forever War.

Oops, I meant, A SEPARATE WAR.

The naked shower scene in Starship Troopers was a rip off from Forever War, but missed some dark, very military wisdom.

Anything not forbidden is mandatory, so the Forever War, high IQ drafted, coed 50:50 boot camp squad had a roster assigning who slept with whom, changing each night. Implicitly, sleep with means sex, or at least privileges the hornier bed partner.

If minimizing jealousy, harassment or coerced sex is the object, the roster is one bone-headed kludge. No actual service has tried it, but who knows? Remarkably large numbers of observers report very high levels of consensual sex in coed units.

This was calculated offensiveness when written, like Swift’s Modest Proposal, so “rape by the numbers” like calisthenics may be just as offensive today as it may have been then

Haldeman’s protagonist ends up in love or just bonded to a fellow boot – a pattern we find in his latest novellas. The unitary mind that coopts humanity is another plot point that recurs.

You shouldn’t mention the Forever War without mentioning the sequels, Forever Peace and Forever Free. There was a long delay before he wrote the sequels, almost a generation, but they are every bit as good.

Sixth grade after-school TV was the CGI animated Starship Troopers. At the time the CGI was daring in a television serial. I found the characters and their relationships interesting and more complex than other television aimed at my demographic. I was fascinated with the theme of what seemed to be military engagement against what was more a force of nature than a (de)personed enemy.

Early in college I read Heinlein’s novel. I was taken in easily by the writing but extremely disturbed by the content (and how much I enjoyed it). Heinlein was the worst sort of militarist propagandist: you didn’t mind being hit over the head with blatant authoritarianism if it was entertaining. At the time I was organizing protests against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The army was desperate to meet recruitment quotas. My generation is traumatized and maimed — the degree to which we are publicly ignorant due largely to sci-fi-like prosthetics.

The entire situation was a little too nauseatingly a tragi-comic caricature of 21st Century war.

To this day, The Forever War is the only military sci-fi I will knowingly read. It was first recommended to me as an ‘anti-war’ version of Starship Troopers. It is not that. It is not an ideological tract. The Forever War is much better. It feels like real people being made unreal by war. In it I see my classmates who sign on for a third of fourth tour and marching in anti-war protests on their leaves.

While I also hold this book in the highest regard, I hold one of Joe’s other books in the top spot – “All My Sins Remembered”, which depicts the life of a malleable spy named Otto who joined the service right out of college and is perpetually remade into the physique of socio-political characters whom the corporation/government has optimally kidnapped and mind-copied into Otto’s highly-manipulated brain, serving as the pretender to discover secret plots, prevent catastrophic changes, and serve his operator’s interests – whether rational or not. Sometimes this strategy works; more often, it does not – with alarming consequences. Also subjected to hypnotic suggestion, he often finds himself in impossible situations, and although trained to kill in dozens of ways, his artificial personae is easily broken by stressful circumstances and when he reverts to being just Otto, his implanted training and skills are cast aside in reverting to an imperfect survival mode that finds him desperately fighting just to survive the disaster in which he has been planted. Plenty of morality, compassion, swashbuckling action, and deep introspection, overlaid with the effects of the cruel, icy contempt of government agendas.

I think I was around 16-17 years old when I first read a copy translated into swedish. I remember how I found the story captivating as well as believable, although young I had already a great interest in science, math and physics. It also suprised me when I quite some years later decided to re-read it but in english and found that their first visit back to earth was nothing like I remembered it. How it was much longer and different, so it’s nice to have an explanation for that more than “I must have simply forgotten it” which I didn’t really believe was the case. Rather I thought it was a weird case of translation glitch or something.

I really like Haldemans books and The Forever War will always hold a special place for me. Ever since I did my conscript duty when I was 19 I’ve always kept a foot with the military, although now a days I work as a psychologist with youths mainly. And while I really appreciate Haldemans sci-fi novels I also greatly enjoyed 1968 simply because it gave a very believable story about an unwilling soldier, the pain that followed and lastly a way to find happiness. Perhaps that was in some ways the spark for my master degree assignment, exploring veterans process of coming home. What the obstacles are and what they found as helpful.

To those who pointed out all the other books Haldeman has written, in my own defense, I barely had enough room in this article to mention all the great things he did in this book alone! :-)

It’s really ironic that Joe had this degree in astronomy, so they made him an engineer, digging up and defusing land-mines. In the incident in which he was wounded, I understand the man standing next to him lost his legs. Joe was luckier: to this day, shrapnel still works its way to the surface of his legs.

My favourite book of all time.

I first stumbled across it whilst on a tour of duty in Northern Ireland with the British Army in 1978.

I had found another of Joe’s books “Mindbridge” beforehand in amongst a box of books and enjoyed it immensely. I saw in the Mindbridge foreword that he had another book (The Forever War) and wished that I could get my hands on it, imagine my joy when one of my colleagues casually handed me the Forever War saying that he had just finished it, and despite not being a fan of Sci Fi that he had enjoyed it immensely.

That was the start of a long love affair with Joe’s books for me, All My Sins Remembered is – as has already been said – a fantastic but underrated novel and I would highly recommend you find a copy of “There Is No Darkness”, which Joe co-authored with his brother Jack. It’s brilliant.

A few years ago I stumbled upon Joe’s email address online, I bit the bullet and emailed him. To my deep joy he responded within days (and has responded to subsequent emails too). A real gentleman and easily my favourite writer.

@21 Haldeman is not only a good writer, he is a good person. Your listing of his other works is whetting my appetite to read more…

Alan, The Accidental Time Machine should also be on the list, along with Worlds.

Enjoy

I keep trying to recommend this book to people, especially with how OIF1/2 OEF was echoing the Vietnam sentiment in my time in the service. It was a disheartening read especially right after reading Starship Troopers which of course they had a different song playing. It sparked a great interest, at least for me, about the Vietnam war and settled a great amount of respect for Vietnam veterans. I always looked forward to talk to vets from No Slack 2-327th, my unit, during eagles week.

I had no idea there were different editions of the Forever War with more about Earth in the middle section. How do I find out which edition is which? The only ones I’ve seen entirely omit the community farm bit, so I’d like to locate an unabridged edition. Advice/pointers welcomed.

@25: All editions after 1991 should include “You Can Never Go Back”, post 1997 editions are corrected and “definitive”.

@26: Ta! So I am looking for a post-1997 edition. Thank you muchly!