Recently I experienced a delightful wave of nostalgia when the Hard Wired Island Bundle of Holding showed up in my inbox. This roleplaying game and its spin-offs were set in a Solar System that featured good old fashioned space colonies of the sort proposed by the late Gerard K. O’Neill.

I was a big fan of space colonies as an impressionable teen; I’m also a big fan of roleplaying games. This bundle hit the sweet spot. And prompted this essay.

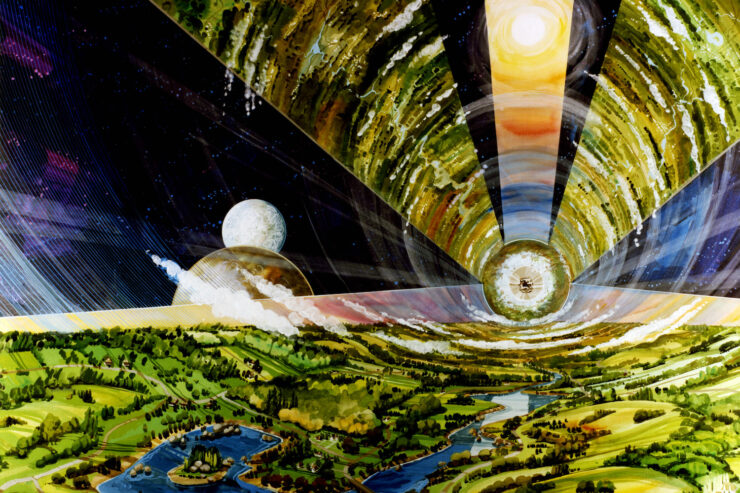

As you know1, proposals to establish permanent communities in space did not begin with O’Neill. Nor was he the first person to focus on settling asteroids. But it was his book, The High Frontier, that really captured popular attention. O’Neill’s talent for promoting his vision, and the eye-catching illustrations by Don Davis and others, ensured that O’Neill’s scheme achieved remarkable fame. Cox and Cole may have promoted space colonies before O’Neill did, but Cox and Cole were never profiled in National Geographic.

It is a bit surprising that those imagined Island Threes and Bernal Spheres didn’t retain an ongoing presence in US science fiction. Sure, they aren’t realistic, but neither are FTL drives and there is no shortage of those in US science fiction…

As I’ve mentioned previously, I suspect it comes down to the fact that O’Neill-style space colonies are basically cities2. In many cases they seem to be ’70s-style suburbs, but even a suburb is a rudimentary urban environment. For reasons that my editors may be relieved to know I don’t have space to go into, US science fiction generally does not care for cities and O’Neill made his pitch in a time when cities were viewed with particular suspicion.

But the idea didn’t completely die. Herewith, find five works featuring O’Neill-style space colonies, starting with the book that began it all.

The High Frontier by Gerard K. O’Neill (1976)

While The High Frontier is for the most part non-fiction, O’Neill illustrates his proposals with imaginative scenarios. Perhaps aware that the glowing descriptions of lavish apartments, terraces, and gardens might not appeal to all, O’Neill provides an entirely different homesteading effort. This centers on the space craft Lucky Lady.

The Lucky Lady costs about as much as a terrestrial home3, and is large enough for a nuclear family, pets included. Accompanied by four similar space craft, the Lucky Lady conveys a stalwart family of pioneers to the asteroid belt, to search for a promising rock and establish a small community there.

I think there is tremendous story potential here4. In fact, O’Neill’s mind clearly headed down the same path my mind did, because he takes the time to assure readers that dental and medical care are available once the Lucky Lady reaches the asteroid belt. If such social services aren’t there, well, there are all kind of adventures for which small groups of pioneers are ideally suited, adventures such as Roanoke or the Donner Party.

Babylon Five, created by J. Michael Straczynski (1994 to 1998)

The galaxy having previously been a hotbed of interspecies strife, the Babylon Project hoped to provide a venue in which differences could be resolved peacefully. Thus far, the effort has not been without setbacks—three of the previous four Babylon stations were destroyed before completion, while the fourth just up and vanished—but Babylon Five is finished and open for galactic diplomacy.

As the station’s diverse cast of characters5 soon discovers, convincing civilizations accustomed to unrelenting war and exploitation that there is a better path is not a straightforward undertaking. Plus, there are forces driving conflict, forces of which humans, Minbari, and the other powers resident in B5 are only dimly aware. The violent history of the galaxy is no accident.

The B5 series was notable for pioneering intensive use of CGI on television. I understand that to kids these days CGI is ho-hum, but it was pretty exciting stuff in the 1990s, because it made possible lavish spectacle on a modest budget.

Mobile Suit Gundam Wing, produced by Hideyuki Tomioka (1995–1996)

The Earth–Moon’s five Lagrange points are filled with O’Neill colonies. All of these communities are ruled by the United Earth Sphere Alliance, which tends to be a mite, um, heavy-handed. The colonies are outgunned by the Alliance, so independence or even relaxed rule appear unlikely.

The key to freedom is, as it so often has been in the past, extremely powerful mecha. Earth may have lots of conventional arms, but the colonies have durable Gundanium alloy, from which prodigiously powerful Gundam mecha can be constructed. Any single Gundam can and will express the colonies’ sincere requests in a manner that’s hard to ignore. The colonies have five Gundam.

For those viewers who are new to Gundam and who find this anime enthralling, good news. Just this one series is not the end! There are too many Gundam spin-offs for me to list here, enough to keep fans busy for years.

Jovian Chronicles, created by Marc-Alexandre Vezina, et al. (1997)

By 2210, O’Neill colonies can be found as far from the Sun as Saturn. Mars and Venus have been terraformed. This settled Solar System could be paradise… if only it were not divided between hostile governments, which are manipulated behind the scenes by powerful financial concerns. Conflict is certain. And how will this conflict be managed? As it has been throughout all of human history, with giant mecha. In space.

Jovian Chronicles is a roleplaying game produced by the sovereign nation of Canada’s own Dream Pod 9. “Nightmarish interlocking dystopias” is just another way to spell opportunity for thrilling adventures.

Was this game inspired by Gundam? Perhaps. There’s a long Japanese tradition of anime and manga mecha. This Wikipedia article traces the mecha trope back to 1948—or perhaps in a human-piloted form to 1973. Even if one isn’t a mecha fan (I am not) Jovian Chronicles is a solid hard SF (aside from the mecha) roleplaying game.

Hard Wired Island, created by Paul Matijevic, Freyja Erlingsdóttir, and Minerva McJanda (2022)

Following 1996’s catastrophic meteor impact, the nations of the world worked together to give Earth the defenses it so desperately needed. This effort was wildly successful. Among its most notable achievements was Grand Cross, an O’Neill cylinder in the Earth–Moon L5 point.

Officially completed in 2013, Grand Cross is the gateway to the Solar System. The question is, to what exactly will Grand Cross be the gateway? A new era of freedom and prosperity? Or will the oligarchs of the Offworld Cartel commandeer Grand Cross, and through it the Solar System?

Like Jovian Chronicles, Hard Wired Island is a roleplaying game. However, the focus isn’t on anime-inspired mecha, but on retro-futuristic cyberpunk social struggle… IN SPACE.

Did I miss any of your favourites? Feel free to mention them in comments below.

- Bob.

- From a writer’s perspective, cities you can spin up anywhere might not be as inspirational as terrestrial cities. Terrestrial cities are where they are for historical and economic reasons. That’s the stuff of inspiration because a story set in New York is very different from one set in London. I suspect in practice a space city would also be subject to economic and historical forces—you do not want to live in Space Petra after the Space Romans eliminate the trade route on which your city depends—but working out what those forces would be in space might involve more orbital mechanics than most authors care to grapple with.

- In part because it uses refurbished parts. “Refurbished parts” is definitely a phrase you want to hear in reference to the life support system on which you will depend, many AU away from help.

- Perhaps Katherine MacLean agreed, because her “The Gambling Hell And The Sinful Girl” (mentioned in a previous essay) reads as if Maclean had O’Neill’s Lucky Lady in mind.

- B5 offers much the same advantages for accommodating a wide range of species as do James White’s Sector General Hospital books. In fact, I’d have mentioned Sector General… if it didn’t long predate O’Neill.

There’s a Babylon 5 Rewatch going on here:

https://reactormag.com/tag/babylon-5-rewatch/

Niven’s “Ringworld” could be considered an orbital habitat…

There’s also his, “Integral Trees”, if Ringworld is considered a relative…

I’m amused to note that I’ve been here long enough to know exactly what footnote 1 would say before going down to read it.

My 2012 novel Only Superhuman from Tor and the subsequent stories I’ve written in that setting, including “Conventional Powers” in Analog, take place in a very High Frontier-inspired Asteroid Belt, where most populations live in space habitats orbiting the asteroids so they can live in reasonably high gravity, which they couldn’t do if they settled the asteroids directly.

On similar lines to what you mention in footnote 2, I put a lot of thought into developing the “Striders” (my name for asteroid-dwellers, since “Belters” is too generic) into various distinct subcultures based on their regions, because I got tired of the uniform “Belter” cultures in other SF. For instance, since Ceres is the richest lode of water and organics, it’s the center of civilization, basically the NYC and East Coast of the Belt; while Vesta, the largest silicate asteroid which is short on water, is more like LA or Las Vegas, where civilization has made the desert bloom to take advantage of its mineral wealth, and where the richest, most prosperous communities tend to be found, though they’re less politically unified than Ceres. The Outer Belt has more small asteroids rich in water and carbon, so it’s the boondocks where small, weird fringe communities can thrive independently of the major asteroids like Ceres. And Pallas, which is rich in water, carbon, and minerals but has a highly inclined orbit making it hard to get to, is a lawless “pirate island” controlled by warlords who raid the Belt when Pallas passes through the ecliptic about every 2 1/3 years.

https://christopherlbennett.wordpress.com/only-superhuman/

Ah yes, the space colony, it’s a nice idea, but probably a dead end.

Not that that stopped Joan D. Vinge from imagining her Heaven Chronicles in 1978 / 1991, in which the crew of the Ranger have to deal with Belters in the asteroids of Heaven’s Belt. So it’s mostly about the Ranger crew but also what happened to the people living on (in?) the asteroid colonies.

Do remember that Las Vegas and LA “made the desert bloom” because of huge money transfers from the damper parts of the US to build their water supply systems.

I don’t think it’s a dead end. Artificial habitats are the only way to get Earthlike gravity and environment in space, short of terraforming Venus, which would take millennia. Humans probably can’t thrive in Martian or Lunar gravity, so habitats would be the only option, other than radical transhuman engineering. And the land area that could potentially be constructed from the material of the asteroids and comets could collectively be thousands of times the land area of Earth.

It is far, far too early to say humans can’t thrive on Mars or the Moon, especially as there have been no long term experiments in how little gravity is required by humans.

What we currently know suggests that lack of adequate gravity would negatively impact fetal development, bone growth, etc. Our models should be based on the evidence we have. It goes without saying that new evidence in the future could require us to update our models, but it makes no sense to get ahead of the data and assume our current models are wrong. Just because there’s a nonzero level of uncertainty doesn’t mean we know nothing at all.

Also, even if it is possible to thrive on Luna or Mars, that is in no way an argument against building space habitats, since there’s no reason why they should be mutually exclusive. Indeed, most fictional universes that depict humans in the Solar System living in space habitats also depict them living on Mars and various moons, including Niven’s Known Space, the Gundam franchise, The Expanse, and my own Troubleshooter series. After all, why settle for living in 17% or 38% gravity if you can build a habitat that gives you any gravity level you want? In my fiction, I assume most habitat-dwellers choose to live in gravity 10-15% lower than Earth’s, which would have health and longevity benefits without being too low to affect development.

In what I am sure is a complete coincidence, most planets in the solar system have surface (or “surface”) gravity similar to Earth’s. The exceptions are Mercury, Mars, and Jupiter. Venus surface gravity is 0.9x Earth’s, Saturn 1.07, Uranus 0.92, and Neptune 1.12. Venus even has a region with reasonable temperature! 50 km above the surface.

Obviously, the planets are not otherwise attractive places to live.

I’ve written about floating cities in the habitable region of a Venus-like planet’s upper atmosphere in Star Trek: The Original Series — The Captain’s Oath, and I’ve long considered using the concept in my original SF. But such cities would be a form of artificial habitat in themselves, not profoundly different from “High Frontier”-style habitats.

The figures you cite for Saturn and the ice giants are for the tops of their cloud layers, so they don’t really count as surface gravity. To me, the real coincidence is that Mercury and Mars both have 38% gravity. Mercury is smaller but denser, so it balances out. I would imagine that if there were mining facilities, power plants, or the like on the surface of Mercury, they’d tend to be crewed by Martians.

Footnote 3. OceanGate Titan, eh?

Arkady Martine’s fantastic Teixcalaan duology features some good looks at space colonies, particularly A Desolation Called Peace.

Becky Chambers’ Record of a Spaceborn Few is an excellent slice of life look at living on a space station colony.

And of course there is The Expanse by James SA Corey, which features a bunch of colonized asteroids throughout the Asteroid Belt and then Medina Station later on in the series.

The thing about cities is that they are built where people find it easy to live, and tend to be close to fertile fields and harbours.

And the thing about space colonies is that they would be in the middle of thousands of kilometres of hard vacuum. Where it is not easy to live. People live where the cost of living – and the cost of life support – is cheap. Why would you build a city there rather than on Baffin Island?

To your first point, that’s why my Strider habitats are in orbit of resource-rich asteroids like Ceres and Vesta. Ceres has more fresh water (in ice form) than Earth does, and probably abundant organic compounds, so in my series it’s the primary source of water and organics, not just for the Main Belt, but for the whole inner system (besides Earth) as well, since it’s easier to ship them in from the asteroids than to haul them up out of Earth’s gravity well. (This is something I guessed right on in Only Superhuman, while the writers of The Expanse guessed wrong that Ceres was iceless. But they’re the ones who got the lucrative TV deal — sigh. In the TV show, they handwaved it in the first episode by having someone say Ceres used to be covered in ice but it all got stripped away by Earth and Mars.)

As for living in vacuum, I read an argument recently — I forget where — that people who live in cities on Earth are just as dependent on artificial environments for survival. I doubt most of us could live off the land without our solid-walled homes, heating and cooling systems, paved roads, electric grids, grocery stores, etc.

That analysis ignores many salient differences, starting with Earth cities not losing a breathable atmosphere if the A/C goes out. People can and do live without many of those things, including sometimes on city streets. It’s not ideal, but it’s not universally fatal. Similarly, in the event of a mass disruption of infrastructure, people can leave and/or aid brought in in a timely fashion (this isn’t always what happens, but when it doesn’t that’s a matter of politics, not physics.) Take the recent Palisades fire; ~105,000 people were evacuated elsewhere, and about 30 people died. In Space!Los Angeles, where are those people going to go if there’s a massive fire in the habitat? What’s that going to do to the air supply of the other three million inhabitants? What if it was an impact that did similar damage? Then how many casualties are we looking at?

Obviously no analogy is meant to be exact, but that doesn’t make it invalid. It’s not claiming the two are identical, just that the distinction is not as fundamental as often assumed.

For one thing, people overestimate the danger of atmosphere loss. In a large habitat of the sort featured in The High Frontier, it would take hours or days for any significant pressure decrease to result from a hull breach — plenty of time to patch it, or at worst, to evacuate.

Any impactor sizeable enough to cause a catastrophically large breach would, of course, be tracked well in advance. Astronomers on Earth are doing everything they can to identify and track every object that could pose a danger to Earth; by the time we colonize space, we should have a quite complete catalog of every significant body and be able to predict its course decades in advance. In the Main Asteroid Belt, contrary to the myths of fiction, a habitat might get struck by a small meteoroid something like once a year and a large one maybe once a century, on average (though habitats that settled in the Kirkwood gaps, cleared of most debris by orbital resonance with Jupiter, would be at a lower risk). But the large ones would be tracked and could be diverted before impact, especially if the Belt is colonized by asteroid miners who move rocks around as a matter of course. In my Troubleshooter universe, habitats have drive beams which they use to accelerate and capture magnetic-sail craft; those could easily enough be used as asteroid defenses if it came to that. Also, unlike Earth, a habitat could move itself out of the way of a large asteroid if it had to. As for smaller micrometeoroids, you’d shield a habitat’s skin with several outer ablative layers with vacuum between them, which would vaporize small impactors and prevent the heat or damage of the impacts from reaching the interior.

As for fire, that’s much less of a risk in a habitat than in Southern California. Weather inside an artificial megastructure would be pretty regular and predictable, so you wouldn’t have any long drought periods to dry out the vegetation. And the Coriolis winds would be in a constant direction, so you wouldn’t need to worry about the wind shifting and spreading a fire in an unexpected direction. You could perhaps design a habitat with a network of canals dividing it into different sections, so that any fire could only spread so far. A habitat might even have physical partitions between different sections, so that if a major breach or fire occurred, only that one section would be affected.

One possibility, if necessary, would be to halt the habitat’s rotation; in free fall, fire smothers itself because the carbon dioxide it produces doesn’t convect upward but lingers around the flame. That would also shut down the Cori winds.

Halting a habitat’s rotation is unlikely to be trivial, unless a lot of resources that would be better used elsewhere are reserved for this project. I suspect that making a habitat easily haltable would also require more strength along axes that wouldn’t matter in a stable habitat, but I’m not enough of a structural engineer to be sure.

I missed this reply before. I was brainstorming possibilities, but I agree that halting rotation would be problematical, at best a last resort when all else fails, but things are unlikely to get that far if other reasonable safeguards are in place. It might be doable in a small habitat/station or a spaceship with a rotating habitat section, but less feasible in something large like an O’Neill cylinder.

Based on recent incidents in the SF Bay Area, I’d be most worried about some industrial facility catching fire and filling the surrounding area with toxic smoke. For more fun, imagine some of the illegal and print to fire chemistry set-ups that you get in dwellings.

And then there’s agriculture. The worst air quality incident I’ve been exposed to was when a mushroom farm near my work caught in fire. Imagine weeks where the entire region was supposed in the smoke from burning manure…

The designs for space habitats usually have the industrial stuff in separate modules from the habitat section. After all, aside from the logic of isolating the habitat’s environment from pollution and waste heat, a lot of industrial processes would benefit from free fall, so you wouldn’t want them in the rotating part of the hab anyway.

Most designs I’ve seen also put the agricultural section in separate modules, their conditions tailored to optimize productivity. It would really make no sense to cram everything into a single module.

In John Varley’s Titan series, there’s a trade in second hand space colonies that came on the market because all of the previous inhabitants died thanks to community-wide fatal mishaps.

“Delilah and the Space Rigger” by Robert Heinlein

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delilah_and_the_Space_Rigger

“Orbital Decay (Near-space)” by Allen Steele

https://www.amazon.com/Orbital-Decay-Near-space-Allen-Steele/dp/0441498515

Poul Anderson, Tales of Flying Mountains

If Ringworld counts, then Bank’s Cultureverse Orbitals do.

Bujold has Kline Station and Quadispace. Cherryh has Stations is several setting, and also ships where are effectively small travelling space colonies.

Quaddiespace always struck me as the most sensible reason for a space station society- the inhabitants need variable/no gravity.

Kline Station’s public health provisions were interesting.

Bruce Sterling’s excellent Schismatrix starts in orbital colonies and moves out to the asteroids.

The Cities in Flight series by James Blish solves this one by cheating and taking Earth’s cities into space using the Spindizzy drive, an antigravity / FTL drive which also provides a force field to hold the air in – I don’t recall much discussion of how the air is recycled or what they do in the event of a catastrophic drive failure, other than probably die very quickly. It’s notable that they don’t seem to use this tech for space colonies etc., the cities are nomadic workers, finding colony planets that need their speciality (e.g. mining), working there for a few years, then moving on to the next job. This does make one sort of space colony story more or less impossible – they will die if they don’t have educated leadership and a large educated work force, so “forgot they were aboard a space station and reverted to savagery” scenarios are unlikely.

As I recall the main solution to drive failure is redundancy. New York has one constantly failing spindizzy that eventually fails and needs replacement, but the other units are evidently sufficient to keep the atmosphere in.

The cities seem to be a product of particular economic conditions– all are from Earth (or Mars) during a millennium or so, and everyone else uses spaceships to colonize the many Earthlike planets.

Though the Vegan Orbital Fort is sort of an exception. But it didn’t become a self-sustaining colony by original intention, and has no imitators that we see. And there’s at least one mobile planet that uses spindizzy tech, though again it doesn’t seem to become a widespread phenomenon.

Sorry to keep plugging my own books, but on the question of why a civilization would live in space instead of on planets, the ancient, multispecies galactic civilization in my Arachne series (Arachne’s Crime, Arachne’s Exile, and the upcoming Arachne’s Legacy) lives mainly in space habitats and megastructures because they want to allow other species on their planets the opportunity to evolve sapience and civilization of their own. Any planet that produces one sapient species will probably produce others (we have hominids, cetaceans, elephants, cephalopods, and corvid birds as likely candidates), so if one civilization continues to monopolize its planet, it could prevent other species from getting their chance to evolve. And in this universe, planets where sapience evolves are not extremely common, so you want to allow as many opportunities for it to happen as possible. So it’s considered a matter of basic responsibility to leave one’s birth planet behind so it can be a cradle for the next generation of sophonts. The main aliens in the trilogy, the Chirrn, live in O’Neill-type cylinders that wander between stars, while a range of other types of megastructure are seen in the second and third books.

I don’t know if you would consider them “colonies” precisely, but a more modern work I liked involving living in tin cans in space is Stephenson’s Seveneves.

John Scalzi’s The Interdependency series trilogy.

As noted by Cardenia aka Emperox Grayland II, there is only one livable planet, End.

All of the Interdependency citizens otherwise live in space habitats.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Collapsing_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Consuming_Fire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Emperox

I believe there’s a fair number who live in completely enclosed ground habitats–might as well *be* space stations, but they bury them.

The Red Rising comes to mind as well.

I would bring to the table :

Deepness and its sequels are amazing books, but the way Vinge decided to spell “Qeng Ho” grates on me. The group is supposedly named for the Ming Dynasty trade fleet leader whose name is spelled Zheng He in the pinyin romanization system and Cheng Ho in the older Wade-Giles system, but Vinge seems to have mistaken Wade-Giles “Cheng” (Zheng) for “Ch’eng” (Cheng) and “Ch’eng” for “Ch’ing” (Qing), so it ends up being a complete hodgepodge.

Wow, I’m familiar with Zheng He and with Chinese romanization but I never made this connection!

In Arthur C. Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise, all of humanity ends up living in an orbital ring surrounding the Earth, essentially occupying the geosynchronous orbit of the planet. There was something similar in his 3001: The Final Odyssey, as I recall.

There’s a nontrivial population in the orbital ring in the epilogue. The largest portion of the human population seems to have emigrated to a terraforming Venus, although there are also populations on Mercury and Mars.

(There has been an especially severe temporary downturn in solar activity that has turned the Earth into a snowball. For reasons that appear to have been basically philosophical, humans have temporarily abandoned Earth.)

(Just to clarify, the Mars settlements started before the solar downturn.)

Alastair Reynolds Glittler Band !

Susan Shwartz COLONY FLEET–the tests are supposed to be rigged, too bad our heroine picked the day when some asshole reformer decided to fix that. Oops. But she copes well dealing with a whole new social class she had no idea existed.

Joe Haldeman’s “Worlds” trilogy is set in an orbital habitat, New New York. The first novel featured several neighboring biomes with different politics and philosophies.

I feel it should be “Newer York.”

In the long out of print RPG Other Suns, one alien species split in two along preferred habitat lines. Some of them preferred habitable planets. The others were content to live in habitats in systems without habitable planets, systems that nobody else wanted.

Another way to look at it is that the rules, based on a now obsolete planetary formation model, dictated that only half the stars formed planetary systems, which meant the habitat dwellers had half or more of the galaxy to themselves.

Liege Killer, Ash-Ock and Paratwa are set around multiple O’Neill cylinders including a dedicated winter sports environment.

Chris[topher] Brookmyre is mostly known for Tartan Noir (except recently, when he’s been collaborating with his partner on Victorian-era medical related mysteries), but Places in the Darkness is a respectable story set in a habitat roughly halfway between Earth and the Moon. (Includes, per my comment above, an improbably rapid halt to station spin.)