Leonora Carrington was a surrealist painter and writer. She lived from 1917 to 2011, making her the last living surrealist. Here’s a thing, though: I’m not so sure she was a surrealist?

Like previous TBR Stack author Anna Kavan, Leonora Carrington went mad for a while, did a stint in an asylum, and wrote about it later. How many creative women have gone mad? And is it madness when you fall into despair at the state of your world? In Carrington’s case because her lover, Max Ernst, 26 years her senior, ditched her and fled into the American arms of Peggy Guggenheim when the Nazis invaded France.

I mean I can’t entirely blame him? If the Nazis come for me I don’t know what I’ll do—but I hope I’ll have the good grace not to leave a trail of terrified people in my wake. I hope I’ll find a way to bring them with me.

But Carrington got through it—went mad and healed, escaped her family, and spent the rest of her life on her own terms writing and painting and creating an international cross-cultural feminist dialogue between her home base of Mexico City and New York. Her complete stories have been gathered for a collection that is disturbing and gorgeous and everything I want in my brain.

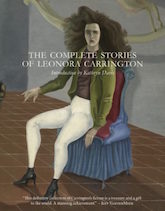

Buy the Book

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington

So about that Ernst thing…in Carrington’s own words: “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse … I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” And obviously I don’t want to put my own modern theoretical crap on a woman from an era before my own, who was struggling with a level of oppression I have largely avoided thanks to the women before me, but looking at her life and her writing it seems to me that she wasn’t wrestling with any Freudian jargon or any ideas of herself as channeling a prophetic feminine energy or any of the other things men of that era liked to declaim about at length. She was living during a terrifying time, subject constantly to the desire of family member and older men who all thought they knew her mind better than she did, and she ended up lashed to a bed in an insane asylum in excruciating pain, being pumped full of hallucinogens.

Her fiction seems pretty realistic to me.

“The Oval Lady” reaches right into the heart of Carrington’s girlhood, with a protagonist named Lucretia who both loves her rocking horse, Tartar, and can herself transform into a horse…which is also snow. The pair run together, and even though the snow-horse-girl and the rocking horse appear to be traveling impossibly fast, they’re also holding still, so the girl’s furious Aunt is able to accost her and drag her off to face her father. Her father lovingly explains that she’s too old for rocking horses, and burns Tartar while the girl melts into the floor. This would just be so much suggestive surrealist sexual awakening, except the narrator, a guest of Lucretia’s can hear Tartar screaming in pain as he’s burned.

This isn’t just a dream or an idyll or a fancy. Lucretia is gone, truly, and the sentient rocking horse is being burned alive, his pain no less real than anyone else’s.

Hyenas disguise themselves as women, and it takes other humans hours to realize the ruse. Smells are described in terms so vivid they become their own characters. Meat rots, bluebottles swarm, women become horses, become moles, become fire, become smoke. Men are largely ignored. Women walk out into well-kept gardens only to realize, much later, that they’re wandering through thick forests.

…I think there might be a metaphor there? I can’t quite put my finger on it.

The true heroes of these stories are the animals, though. And they’re not just metaphors for other things, they’re not some tired Freudian nightmare. They’re individuals. Most can speak—hell, many are multi-lingual. Over the course of the collection we meet Moles who work for Jaguars, who dive into hard ground “as if it were water.” When a girl comes home to find her father in a violent mood, she realizes she should be afraid because her cat is afraid, and then fears that her father will kill her “like a chicken.” A bird speaks with a human voice, while, on multiple occasions, horses prove to be trustworthy guides. In one of Carrington’s most famous stories, “The Debutante,” a fractious young girl rebels against her stuffy family by ducking out of a ball. She sends her BFF in her stead—her BFF being a hyena. Much to her mother’s annoyance, the hyena has to eat the girl’s maid in order to acquire a human face to wear. Society balls are always so annoying!

The early stories in the collection circle and circle around images of oppressed young women, bloody animals, and baffling social norms that shift constantly to stymy the girls’ intermittent attempts at good behavior.

In the long, twisty “As They Rode Along the Edge” a woman named Virginia Fur has a strong musky smell and a mane of wild hair, but she gets along fine with the people of her mountain. “True, the people up there were plants, animals, birds: otherwise things wouldn’t have been the same.” The story reads like a proto-Mononoke Hime, with Virginia creating a lasting relationship with a boar named Igname, and an ongoing clash between the forces of civilization—living Saints and society ladies—and Virginia’s family of cats and boars. When the Saint, Alexander, attempts to win Virginia’s soul he takes her on a tour of his “garden of the Little Flowers of Mortification”:

This consisted of a number of lugubrious instruments half buried in the earth: chairs made of wire (“I sit int hem when they’re white-hot and stay there until they cool off”); enormous, smiling mouths with pointed, poisonous teeth; underwear of reinforced concrete full of scorpions and adders; cushions made of millions of black mice biting one another—when the blessed buttocks were elsewhere.

Saint Alexander showed off his garden one object at a time, with a certain pride. “Little Theresa never thought of underwear of reinforced concrete,” he said. “In fact I can’t at the moment think of anybody who had the idea. But then, we can’t all be geniuses.”

If you’re noticing that Alexander has an excess of pride for a Saint, and if you think there’s maybe a slight culture clash by the end of the story, you will feel right at home here in Carrington’s mind.

The second half of the collection isn’t as funny, but trades Carrington’s sardonic wit for dark fairytales. “A Mexican Fairy Tale” starts off seeming like it will be a boy’s own adventure, until it shifts into a girl’s perspective, and seems to be dipping into Six Swans territory. But then, abruptly, it turns into an Orpheus and Eurydice underworld quest. But then, abruptly, it becomes a tale of sacrifice that explains the birth of a god. None of these shift are announced—Carrington simply slides us into the next facet of her story with a tiny quirk of perspective or plot, and guides us through her labyrinth before we fully know what’s happening.

In “The Happy Corpse,” a boy undertakes what he thinks will be a journey to the Underworld…but soon finds himself treated to a lecture on the perils of being a grown-up. That this lecture comes from a corpse who can speak out of any of the numerous rotting orifices in its body (“Think of listening to a story told straight into your face out of a hole in the back of the head with bad breath: surely this must have troubled the sensibility of the young man”) does not negate the wisdom of the advice:

My father was a man so utterly and exactly like everybody else that he was forced to wear a large badge on his coat in case he was mistaken for anybody. Any body, if you see what I mean. He was obliged to make constant efforts to make himself present to the attention of others. This was very tiring, and he never slept, because of the constant banquets, bazaars, meetings, symposiums, discussions, board meetings, race meetings, and simple meatings where meat was eaten. He could never stay in one place for more than minute at a time because if he did not appear to be constantly busy he was afraid somebody might think he was not urgently needed elsewhere. So he never got to know anybody. It is quite impossible to be truly busy and actually ever be with anybody because business means that wherever you are you are leaving immediately for some other place. Relatively young, the poor man turned himself into a human wreckage.

But generally speaking, there are no morals here, and the stories are all the more fun and resonant for it.

“The House of Fear” finds a young girl attending a party hosted by Fear, at which all the other guests are horses. But there’s nothing here about conquering fear, or facing fear, or girls being corrupted by their animal natures, or even proper equestrian etiquette. Fear announces that they’re all going to play a game, and the girl tries to play even though, lacking hooves, she’s at a disadvantage. Then the story stops. Because there are no rules for fear. There is no moral to come out of playing party games with her.

In “White Rabbits” our protagonist becomes obsessed with her neighbors, and when the lady across the street asks her to bring rotting meat over, she buys meat, allows it to fester on her porch for a week, and eagerly trots over. She learns that the meat is for a veritable army of white rabbits, who fall to their meal like so many Killer Rabbits of Caerbannog… but the rabbits aren’t the point of the story. The point is that the couple with the rabbits are otherworldly, with sparkling skin and increasingly ominous vocal tics.

In Carrington’s stories, people just have uncanny experiences, and they either survive them or they don’t. I don’t want to belabor her time in an asylum, but the only thing I can pull from this is that having gone through such a horrific experience she understood better than many people that life is chaotic, and sometimes there are no lessons to be learned.

Her stories capture the pure horror and pure joy that can be found when you strip all of your niceness and civility away and embrace life as it is.

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington is out now from Dorothy Books.

Leah Schnelbach kind of wants to live in a Carrington painting now? How can we make that happen? Come chatter to her about hyenas on Twitter!

And is it madness when you fall into despair at the state of your world? In Carrington’s case because her lover, Max Ernst, 26 years her senior, ditched her and fled into the American arms of Peggy Guggenheim when the Nazis invaded France.

I mean I can’t entirely blame him? If the Nazis come for me I don’t know what I’ll do—but I hope I’ll have the good grace not to leave a trail of terrified people in my wake. I hope I’ll find a way to bring them with me.

From what I can tell, the truth is both more complicated and stranger, and makes Ernst not even remotely the jerk you suggest he was. (It’s more accurate to say the she “ditched” him, though I at least would not blame her under the circumstances.)

Summarizing from this article by Carrington’s younger cousin, and from Marina Warner’s introduction to Carrington’s memoir Down Below:

Carrington and Ernst were living in Provence when France declared war on Germany in September, 1939. Max Ernst was arrested by the French government and interned as an enemy alien (since he was German); several weeks later, he was freed, and he and Carrington were reunited. Then Germany invaded in early 1940 and defeated France, and Ernst was arrested again, this time by the Gestapo (he was reviled by the Nazis as a maker of “degenerate art”).

Distraught, and fearing the advance of German troops (I imagine she would probably have been interned as an enemy alien, since she was English), Carrington fled to Spain, ending up in Madrid and then, after her breakdown, in a psychiatric hospital in Santander.

Carrington’s parents (in England) arranged for her to be released so she could be transferred to a sanatorium in South Africa. While waiting in Lisbon for a ship to South Africa, she escaped her parents’ minders to the Mexican embassy. Eventually, a Mexican diplomat she had known in France (now at the embassy in Lisbon) suggested a marriage of convenience as a way of freeing her from her parents’ control.

In the meantime, Ernst was eventually freed (along with several other surrealists), partly with the help of Peggy Guggenheim, in early 1941. At this point Ernst headed for his and Carrington’s house in Provence, but she was of course long gone by then. Guggenheim and Ernst, along with Guggenheim’s ex-husband and his current wife and several children, then made their way to Lisbon — where they met up with Carrington and her new Mexican husband, waiting for a ship to New York. (“A master of understatement, Leonora described those weeks as they waited to go to New York as ‘very weird’. Her own affair with Ernst was not reignited.”) Guggenheim offered to pay for plane tickets for Carrington and her husband, but Carrington refused; Guggenheim noted that her plane out of Lisbon actually flew over the latters’ ship.

I think Ernst is really pretty blameless in all this.

I appreciate the spotlight on this writer and I really look forward to reading her work.

That said, the author has got to do better than use “gone mad” as a some sort of catch all for mental illness. This isn’t Downton Abby. We have words for this stuff even if we don’t have a specific diagnosis.

Just saw the new production by Double Edge Theater (Stacy Klein), Leonora and Alejandro, which is inspired by the collaboration between Ms. Carrington and Chilean filmmaker/comic book writer Alejandro Jodorowsky (best known in sf circles for his attempt to produce a psychedelic film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune). Jodorowsky was sent by his Buddhist guru to Ms. Carrington, and the two produced a stage play, Penelope.

Ms. Klein’s piece is a 60-minute dreamscape, built upon the words the title artists used to describe themselves and their partnership, including Ms. Carrington’s memoir/novel Down Below, The Stone Door, The Hearing Trumpet, and The Oval Lady, as well as Mr. Jodorowsky’s Where the Bird Sings Best, The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodowosky, The Way of Tarot, and Endless Theatre. The stage design was based on Ms. Carrington’s painting, The House Opposite.

It was, at all points, Surreal, supra-rational, and composed of solid wisps of smoke and wavy walls of fantasia: