I was still grieving the loss of Vonda N. McIntyre when I read the controversial interview by Ian McEwan in The Guardian.

Like many others, my initial reaction to his comments was anger: How dare this person ignore the rich traditions of the genre and claim that his work is without precedent while throwing shade at some of our honoured tropes?

Those old “genre vs. literary” anxieties seem to lurk beneath the surface, ever present, waiting for the next opportunity to throw our technosocial microcosms into a tizzy whenever allegiances are declared. In the piece, published on April 14th, McEwan states:

There could be an opening of a mental space for novelists to explore this future, not in terms of travelling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots, but in actually looking at the human dilemmas of being close up to something that you know to be artificial but which thinks like you.

McEwan later clarified his remarks and said he would be honoured for his latest work to be counted as science fiction, citing genre influences such as Blade Runner and Ursula K. Le Guin. But that initial quote has stuck with me, because even his apology made it sound like he is still working to overcome his perception of the borders between science fiction and traditional literary forms such as “the moral dilemma novel.”

In reality, those borders, if there are any left at all, are so fuzzy and permeable as to matter very little.

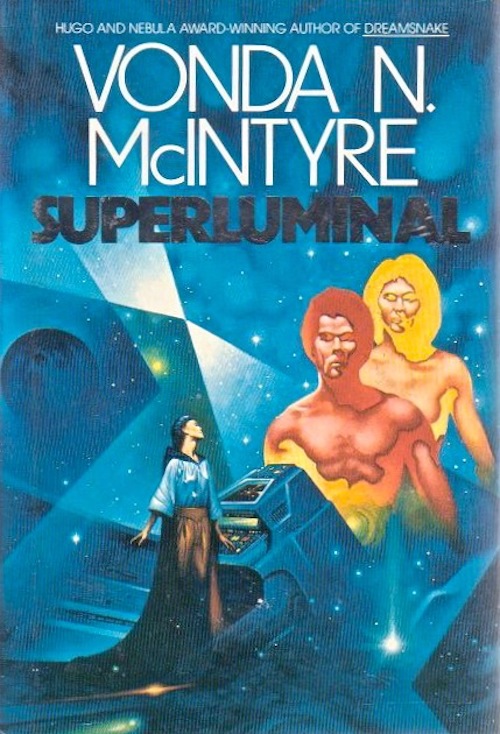

You want moral dilemmas and faster-than-light travel? Let’s talk about one of my favourite books in my personal pantheon of sci-fi legends: McIntyre’s Superluminal.

Sex! Cyborgs! Mer-people! Inter-dimensional exploration!

McIntyre’s 1983 novel has all the markings of classic science fiction. It’s also a story grounded in intersectionality and boundary disruption, far more deserving of intelligent analysis than its contemporary reviewers appeared to believe (a Kirkus review called it “bland,” and I could not disagree more).

Superluminal is one of the fictional works referenced by Donna Haraway in her iconic and prescient 1985 essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” which led me to pick up a copy of McIntyre’s work while studying Haraway in my final year of university.

The part that struck me, after Haraway summarized the narrative, was this:

All the characters explore the limits of language; the dream of communicating experience; and the necessity of limitation, partiality, and intimacy even in this world of protean transformation and connection. Superluminal stands also for the defining contradictions of a cyborg world in another sense; it embodies textually the intersection of feminist theory and colonial discourse in the science fiction.

Obviously, I had to read this book.

“She gave up her heart quite willingly.”

The story opens with Laenea recovering from an operation to replace her heart with a mechanical control, subverting her natural biological rhythms to allow her to experience faster-than-light transit. The pilots are also sometimes derogatorily referred to as Aztecs, an allusion to the sacrifice of their hearts, of their humanity, in exchange for the perception required for interdimensional travel. Laenea is a volunteer cyborg, and deeply committed to her choice despite the problems it poses for her romantic entanglements.

Enter Radu Dracul (no relation). A crewmember from the colonized planet Twilight (nope, no connection there, either). His entire family was lost to a terrible plague during his childhood, a plague which nearly cost him his own life before the introduction of a timely vaccine which may have had unforeseen impacts. He has a distinctive sense of time that leads to unprecedented discoveries.

Laenea and Radu engage in a whirlwind romance that culminates in the realization that there are reasons for the distancing between pilots and crew due to their sensitive, disparate chronobiology. Laenea does indeed give her heart up quite willingly, in both cases. Her choice between human connection or experiencing superluminal transit is a rich dilemma, especially as that connection becomes essential to finding her way home.

Orca is the third protagonist, a character who makes me wish I could read an entire series just about her and her extended family—including the whales she refers to as “cousins.” She is a diver, a new species of humans genetically engineered to exist on either land or sea and who can communicate with marine life. She brings a necessary perspective to the narrative as someone who has contemplated the vastness of the ocean and all its unexplored depths, observing the edge of the universe and being drawn to the mysteries there.

The patterns the whales used for communication, the three-dimensional shapes, as transparent to sound as solid objects, could express any concept. Any concept except, perhaps, vacuum, infinity, nothingness so complete it would never become anything. The nearest way she could try to describe it was with silence. (McIntyre, Superluminal)

But as the divers debate whether to undergo a permanent and irreversible transition, Orca finds herself set apart from her people, tasked with returning to the limits of outer space and bringing back the knowledge to share with her underwater community.

Laenea, Radu, and Orca each struggle with very human dilemmas while being distinct from humanity—by choice, by chance, or by design.

“A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction,” writes Haraway. The concept of the cyborg asks that we re-evaluate our conception of humans and technology as being distinct and separate.

Characterized by Haraway as a “border war,” the cyborg offers the possibility of radically reconfiguring the tensions between the organic and inorganic. As a metaphor for boundary disruption, authors like McIntyre use the cyborg to complicate our understanding of constructed dichotomies of what is human (and valued), and what is artificial (and exploited).

The cyborg represents something never encountered before. But the cyborg identity proposed by Haraway is not limited to the individual body; it is best encompassed in the relationship of the body to other bodies and other technologies, in a way that complicates the apparent divisions between the self/other. Its radical potential is retained in these relationships as a means to subvert traditional paradigms.

While initially presented in the context of second wave feminist identity in order to address emerging issues of race and intersectionality, Haraway’s cyborg offers a way of reconciling tensions by refusing to (re)colonize them into a homogenized identity muddied by historical preconceptions. McIntyre’s fusion of classic sci-fi with these emergent dialogues is part of an important legacy of boundary transgression in science fiction, from the work of Margaret Cavendish and Mary Shelley to 20th-century icons like Le Guin and Octavia Butler. And the conversation continues as contemporary authors present their own take on the cyborg:

—Kelly Robson does masterful work with her time travelling ecological surveyors in Gods, Monsters and the Lucky Peach. Minh, the protagonist and another “plague baby,” decides that her life and research are enhanced with the aid of her prosthetic tentacles—something normalized by the 2260s, but slightly horrifying to residents of 2024 BCE. The ethics of interference in less technologically advanced societies takes a drastic turn in Robson’s hands.

—In her short story “Egg Island,” Karen Heuler fuses the organic and inorganic with a team of researchers who share a commonality in the use of plastic for their prosthetics. It’s a hopeful tale of evolution and community, of nature triumphing over humanity’s worst excesses.

“Does your arm ever bother you?” Michael asked her.

She looked down at it; it had become familiar, it had become a part of her. “No,” she said. “Not at all. It’s part of me now.”

—In his interview, McEwan also notes his anxiety over automated vehicles and the risks involved in allowing machines to make split-second, life or death decisions. When I first read “STET” by Sarah Gailey, I was turning it over in my mind for days afterwards, re-reading, sharing with friends. The unique structure is itself a disruption of the academic form, and the story is a gut check that should be required reading in any modern ethics class.

There are countless other examples of science fiction in which these tensions between human and machine, the organic and inorganic, are front and centre. Our collective desire and anxiety over technological advancement form the foundation of so many of the most interesting and complex conversations happening in the genre—past, present, and future.

As genre readers, writers, and fans, one of our greatest strengths is our ability to disregard convention in order to imagine something impossible and new. Vonda N. McIntyre was one of those authors who strived to expand those borders, and in doing so she made space for authors like me to grow into the genre.

Superluminal was the first of her books I had ever read, and it provoked many questions and curiosities that I continue to play with in my own writing, adding to the conversations started by her and others like her. And one of the lessons I learned from McIntyre is to always welcome the newbies. So, with that in mind…

Welcome to the conversation, Ian McEwan. I hear you’re a sci-fi fan. I am too.

Rebecca Diem is an author and poet of smart, hopeful speculative fiction. Her work includes the steampunk novella series Tales of the Captain Duke. Rebecca now calls Toronto home and is on a never-ending quest to find the perfect café and writing spot. You can follow her adventures on Instagram or Twitter or visit her website for more stories.

Superluminal is an expansion of the short story “Aztecs” which appears in McIntyre’s collection “Fireflood and Other Stories.” It focuses more tightly on the sacrifice of becoming a starship pilot

I admit I started it, but dropped it because I thought it borrowed too much from Cordwainer Smith’s classic Scanners Live In Vain. Though, in retrospect, I think it used the Smith story as a starting point for a different perspective.

Do catch up, Ian. I read Superluminal right after it came out (over 30 years ago), and right after I read Dreamsnake, and still have my copy. It was so absorbing that I forgot to get off a bus I was riding, and was amazed to find myself back where I’d started.

Glad to hear that MacEwen has heard of Le Guin, who consistently fought the ghettoization of SF throughout her career.

*runs off to reread Superluminal*

The smugness of literary authors who go slumming in genre fiction can be bottomless.

I’m still sore at comments Atwood has made over the years, yet I plan to read her follow-up to Handmaid this fall.

Literary authors who are ignorant of SFF and think they’re deigning to lower themselves to give humanity the gift of raising the genre to previously unseen heights are embarrassing and cringy. They’re the author equivalent of those people who say they don’t watch Game of Thrones to make themselves feel special.

love it, finding forgotten works like this

I too read Superluminal when it came out, thought about it a lot, but as time went on forgot about it, so thanks for the reminder.

jmhaces @@@@@#5

Slug slime, I didn’t watch GOT as I don’t have the appropriate cable package, but more pertinently because after reading the precis’ and reviews I know it’s just not my sort of thing, however I do not poor scorn on those who do watch it nor bring up that I don’t unless asked. It seems particularly ironic that you would make such a claim under this specific post.

I’m all for people watching or not watching whatever the hell they want, as well as for anyone enjoying or not enjoying whatever the hell they want. I just criticized authors who don’t really know SFF and think they’re too good for it and people who think not watching GoT (or any show or movie or whatever) makes them smarter than those who do.

Both groups mistakenly think that something they know nothing about is beneath them, and I think that’s embarrassing and cringy. Which agrees with this article’s opening about McEwan’s snobbish comments.

I honestly don’t see how the fact that you personally don’t watch GoT and don’t bring it up in conversation unless asked nor rag on people who do watch GoT would make my comment which was in no way personally addressed to you ironic in the context of this post.

However, I went back and added “to make themselves feel special” to my original post regarding people who say they don’t watch GoT to make it clearer, since you took offense to it.

And finally: slug slime? Really?

All: let’s please keep things civil, and not take/make things too personally–thanks.

McEwan does indeed need to wake up and smell the hyperdrive fuel. Those of us who’ve read and worked in the genre have known it has a “serious” side forever; it’s never been just anti-gravity boots and blasters. Even when it does include gadgetry, it’s not necessarily bad; there’s plenty of room even for the most escapist stuff in this 14-billion-lightyear universe.

Here’s me from the afterword of my most recent extrusion, going through submission right now:

This is not a new idea. Storytellers have been doing this since the invention of storytelling, at least as far back as Gilgamesh. Those who cannot recognize that are either impoverished as storytellers, or willfully self-blinding: Seduced by a stereotype, and falling for it.

I really need to reread Superluminal. And then make some younger friends read it.

I read one novel by McEwan (“Amsterdam”) and found it heartless and smug. So, annoying though it is to have established authors say dumb things about science fiction, I don’t have enough respect for him as a writer to care very much what he thinks. Vonda McIntyre, on the other hand, was a great and thoughtful writer whose heart showed in everything she wrote. Somehow I never got around to reading “Superluminal” — time to remedy that!

I liked Machines Like Me because I had written a book 2 years ago called Do Robots Dream of Love? but no one said the same things about my book. I’m quite sure Ian read my book before he wrote Machines Like Me because of the similarities in the first half of his book and mine. He took the idea in a different direction and that made his work interesting and pleasing.

It’s ironic to me that an old white guy believes he is so special that an entire genre is essentially not worthy given that much of the technology at his fingertips today is based on ideas and concepts that first started in science fiction; be it books, movies or tv series. I also find it hard to believe that a British author like Ian McEwan has actually not read Arthur C. Clarke’s “Childhood’s End” in which we do not enter space and instead are forced (as a society/planet) to think about our entire existence. How is that not looking at ‘human dilemmas’ of the future?

I have not read any of McEwan’s fiction before; because (frankly) it all looks pretty dull; but now he could write the most interesting book of the last 30 years and I might not pick it up; as clearly McEwan doesn’t need more money in his pocket to elevate his snobbery any higher.

I feel like as a Canadian I need to defend Atwood to the commenter above (lol). But I will say that it is absolutely true that she has said some very unflattering things about the genre and fans that she owes her roots to. Just because she wrote dystopian fiction before dystopian was a ‘thing’ doesn’t mean that her literature doesn’t still fall into that category today. Although she does seem to think that she is also special and excluded from anything like her writing that place her in a science fiction/fantasy sub-category.

I’d like to see a lot more authors give nods to their backgrounds/roots and stop pretending that they are the ‘first’ to ever think of any idea. Originality and unique stories can certainly still come about today; but let’s be honest and admit that likely something somewhere we have encountered in life sparked that ‘unique’ idea. No one of us is so special as to live outside the influence of society; especially any author that has published works over the last 20 years since social media came to be. Anyone who is so oblivious that they believe they are outside the realm of influence is not just snobby, but delusional. Although now that I think about it maybe the best science fiction can be written by someone delusional as at least it won’t be a reflection of reality…

Now I’m off to read a book written when I was born. My favourite type of science fiction, old stories about the future.

@14. mel: I like Atwood and I like David Mitchell even more, but both of them agreeing to participate in the Future Library project shows the degree of ego and concern with legacy some writers indulge in. That you would write a manuscript which will not be seen for a hundred years is just… the height of self-involvement. Yes, it’s supposed to offer hope that there will be a climate amenable to humans, that there will be trees, but c’mon.

How about redirecting things in a true SF manner and instead research alternate means of storage and display of text other than printing on wood pulp. That would be far more ecologically sound.

Rebecca here, just wanted to thank you all for reading this piece and sharing your insights! I’m so glad to see so many thoughtful responses from fellow theory nerds and McIntyre fans. My fave comments/tweets are from those discovering Superluminal for the first time or dusting off their own beloved paperbacks for a re-read because of this article. We’ll carry Vonda’s legacy forward <3

Thank you!