Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

This week, we’re reading Mercè Rodoreda’s “The Salamander,” first published in Catalan in La Meva Cristina I altres contes, Barcelona: Edicions 62 in 1967. Our translation is by Martha Tennent, and first appeared in The Review of Contemporary Fiction: New Catalan Fiction in 2008. Spoilers ahead.

With my back I crushed the same grass that I hardly dared to step on when I combed my hair; I used to tread lightly, just enough to capture the wounded smell. You alone.

Summary

Unnamed narrator strolls to the pond, “beneath the willow tree and through the watercress bed.” As ever when she kneels, frogs gather around her; as she combs her hair, they stroke her skirt or pull at her petticoat. Then the frogs leap away and a man’s reflection appears beside her own. To appear unafraid, narrator calmly walks away. A game of retreat and pursue ends with her back to the willow trunk and him pressing her against it, painfully hard. The next day he pins her against the tree again, and she seems to fall asleep, to hear the leaves telling her sensible things she doesn’t understand. Anguished, she asks: What about your wife? He responds: You are my wife, you alone.

They make love in the grass. Afterwards his wife stands over them, blonde braid hanging. She grabs narrator by the hair, whispering “witch.” Her husband she drags forcibly away.

Narrator and man never meet by the pond again, only in haylofts, stables, the root forest. People in the village begin to shun her. Everywhere, as if “it were born from light or darkness or the wind were whistling it,” she hears the words: Witch, witch, witch.

The persecution escalates. Villagers hang bits of dead animals on her door: an ox head with eyes pierced by branches, a beheaded pigeon, a stillborn sheep. They throw rocks. A religious procession wends to her house, where the priest chants a blessing, altar boys sing, holy water splashes her wall. She searches for her lover in their usual haunts but doesn’t find him. She realizes she has nothing more to hope for. “My life faced the past, with him inside me like a root inside the earth.”

The word “witch” is scrawled in coal on her door. Men say she should have been burned at the stake with her mother, who used to escape on vulture wings into the sky. In spring the villagers build a bonfire. Men drag her out, throw her on the heaped logs, bind her. All gather, from children holding olive branches to her lover and his wife. No one can light the fire, however, even after the children dip their branches in holy water and throw them on narrator. At last a hunchbacked old woman laughs and fetches dry heather, which proves an effective tinder. Narrator hears sighs of relief. She looks at the villagers through mounting flames, as if “from behind a torrent of red water.”

Fire burns narrator’s clothes and bindings, but not her. She feels her limbs shrinking, a tail stretching up to poke her back. The villagers start to panic. One says: She’s a salamander.

Narrator crawls from the flames, past her burning house. She crawls on through mud puddles, under the willow tree, to the marsh. She hangs “half-suspended between two roots.” Three little eels appear. She crawls out to hunt worms in the grass. When she returns to the marsh, the playful eels reappear.

She goes back to the village. She passes her ruined house where nettles grow and spiders spin, and enters her lover’s garden. Never questioning why she does it, she squeezes under his door and hides under his bed. From there she can spy his wife’s white-stockinged legs, his blue-socked feet. She can hear them whispering in bed. When the moon casts a cross-shaped shadow through their window, she creeps out into the cross and prays frantically. She prays to know where she is, “because there were moments when I seemed to be underwater, and when I was underwater I seemed to be above, on land, and I could never know where I really was.”

She fashions a dust-bunny nest under the bed. She listens to him say to his wife: You alone. One night she climbs up under the covers and nestles near her lover’s leg. He moves, and the leg smothers her, but she rubs her cheek against it. One day the wife cleans under the bed, sees narrator, screams and attacks her with a torch. Narrator flees, hides under a horse trough to be poked and stoned by boys. A rock breaks her tiny hand. She escapes into a stable, to be pursued by the wife and harried with a broom that nearly tears off her broken hand. She escapes through a crack.

In the dark of night, she stumbles, hand dragging, back to the marsh. Through “the moon-streaked water” she watches the three eels approach, “twisting together and tying knots that unraveled.” The smallest bites her broken hand. He worries it until he pulls it off and swims away, looking back as if to say: Now I have it! He gambols among “the shadows and splashes of trembling light” while she inexplicably sees back to the spiders in her ruined house, lover and wife’s legs dangling over the side of the bed, herself in the cross-shaped shadow and on the fire that couldn’t burn her. Simultaneously she sees the eels playing with her hand—she’s both in the marsh with them and in the other world.

The eels eventually tire of her hand and shadow sucks it up, “for days and days, in that corner of the marsh, among grass and willow roots that were thirsty and had always drunk there.”

What’s Cyclopean: Martha Tennent’s translation keeps the language simple, focused on tiny details: the skirt with five little braids, the milk-colored maggots, the moon-streaked water, the tender leaves of olive branches as the townspeople try to burn a witch at the stake.

The Degenerate Dutch: The salamander appears to live in one of those rural horror towns with little tolerance for deviation.

Mythos Making: Body horror and mysterious transformation have made their appearances many times in this reread.

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Narrator explains that “inside me, even though I wasn’t dead, no part of me was wholly alive.”

Anne’s Commentary

Mercè Rodoreda’s formal education ended even earlier than Lovecraft’s; her family, though a literary lot, withdrew her from school at nine. At twenty, she married—or was married to—her thirty-four-year-old maternal uncle. Their union required ecclesiastical permission, I guess to shoo away the shadow of incest, but the blessing of the Church couldn’t make it a happy or lasting one. Nor was Rodoreda’s association with the autonomous government of Catalonia to prosper long; with Franco’s rise in Spain, both she and the Generalitat de Catalunya were forced into exile.

She and other writers found refuge in a French castle. There she began an affair with married writer Armand Obiols. This broke up the literary family, but Rodoreda and Obiols stuck together through the horrors of WWII and beyond. In the early fifties, Rodoreda mysteriously lost the use of her right arm and turned to poetry and painting. She returned to longer forms with eclat, publishing her most famous novel La placa del diamant (Diamond Square or The Time of the Doves) in 1962. About the same time she wrote a very different novel, La mort i la primavera (Death in Spring, posthumously published in 1986.) As described, Death sounds a lot like today’s story, fantastical and symbolic, set in a timeless village given to brutal rituals, like pumping victims full of cement and sealing them into trees. The English translator of “Salamander,” Martha Tennent, also translated this novel, and nicely too, I bet, though it may be too extended a prose-poem nightmare for me. “Salamander” was just the right length.

In “A Domestic Existentialist: On Mercè Rodoreda”, Natasha Wimmer nails the narrator of “Salamander” as Rodoreda’s typical woman, burdened by “a sadness born of helplessness, an almost voluptuous vulnerability.” She’s notable for her “almost pathological lack of volition, but also for [her] acute sensitivity, a nearly painful awareness of beauty.” Discussing Death in Spring, Colm Toibin also nails “Salamander’s” strengths:

If the book uses images from a nightmare, the dark dream is rooted in the real world, the world of a Catalan village with its customs and hierarchies and memory. But Rodoreda is more interested in unsettling the world than describing it or making it familiar… She [uses] tones that are estranging, while also harnessing closely etched detail, thus creating the illusion that this place is both fully real and also part of an unwaking world of dream.

Creating the illusion one’s tale is “both fully real and also part of an unwaking world of dream” is arguably what makes any weird tale work, or, as Howard would have it, managing “a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

Rodoreda’s villagers embody the demonic chaos they dread in their local witch, our narrator. She’s been useful to them, they grudgingly acknowledge, in a magico-agricultural capacity: digging garlic, binding grain, harvesting grapes. Then she crosses the line by taking a married lover. Maybe the villagers believe she spelled him into adultery—I can see loverboy promulgating that excuse. Maybe it’s even true, because she is magical. Frogs recognize her amphibian nature and flock to her. Fire cannot burn her because she’s not any old salamander—she’s the legendary one born in and immune to flames. What if her salamander powers also extend to poisoning the fruit of trees and water of wells by her mere touch? There is that odd bit at the opening where in her presence “the water would grow sad and the trees that climbed the hill would gradually blacken.” Or does that simply describe her emotional perceptions or even that, simpler still, night’s falling.

What’s real? What’s dream? What’s magical, what’s natural, what’s the difference?

What’s undeniable is narrator’s passive suffering (or passive-aggressive suffering, as in under-the-bed stalking.) It’s genuinely poignant, either way. I was all, OMG, they’re not going to BURN her! OMG, her poor little broken and then severed hand! Those bastard, phallic-symbolic eels, with their playful cruelty! What comforted me was realizing that since narrator’s a salamander now, she can regenerate that missing hand. And maybe the next time Blondie chases her with a broom, she can drop a still-wriggling tail and distract her tormentor.

That’s if she can resolve her split-frames-of-reference problem. Is she human or animal or half-and-half? Is she of the land or of the water or both? Transformation, a core weird fiction theme, is a bitch for narrator. When thoughtfully worked out, transformation is generally a bitch, as we’ve many times seen in this Reread. For instance, it’s no shoreside picnic going from human to Deep One. Yet even for Howard’s “Innsmouth” narrator, it can end up a joyful event. For Rodoreda’s narrator?

I’m afraid she’ll go on suffering as naturally as the willow roots keep drinking, always and forever. I hope she’ll stay sharply observant and perceptive of what beauty lies in the sinuous rompings of eels, in the shift of shadows and splash of trembling light, in the slow bend of heavy-headed sunflowers, in even the torrents of red water that are unburning flames.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The weird creeps in from all directions—more directions than our own limited mortal experiences can encompass. And in a universe of incomprehensibly many dimensions, even seemingly opposed perspectives can intersect.

Lovecraft’s weird, for example, is a weird of privilege. Perched atop the largest mountain he can see, he writes the vertiginous epiphany of how far there is to fall and the inevitability of the drop—and the existential terror that comes when the clouds part and a larger mountain looms beyond vision, showing one’s own peak to be a child’s mound of sand. The privileged weird is a story of beloved, illusory meaning, forcibly stripped away.

The weird of the oppressed, though, makes story out of the all-too-familiar experience of chaotic powers imposing their whims at random, of vast powers and faceless majorities casting aside one’s existence out of malice or convenience or mindless focus on their own interests. No shocking revelations, just a scaling upward and outward of everyday horrors. There are a thousand kaleidoscopic approaches to such scaling, of course: giving the horrors meaning or portraying its lack, mocking the oppressive powers or railing against them, absurdity as a window on how to fight or on a sense of futility.

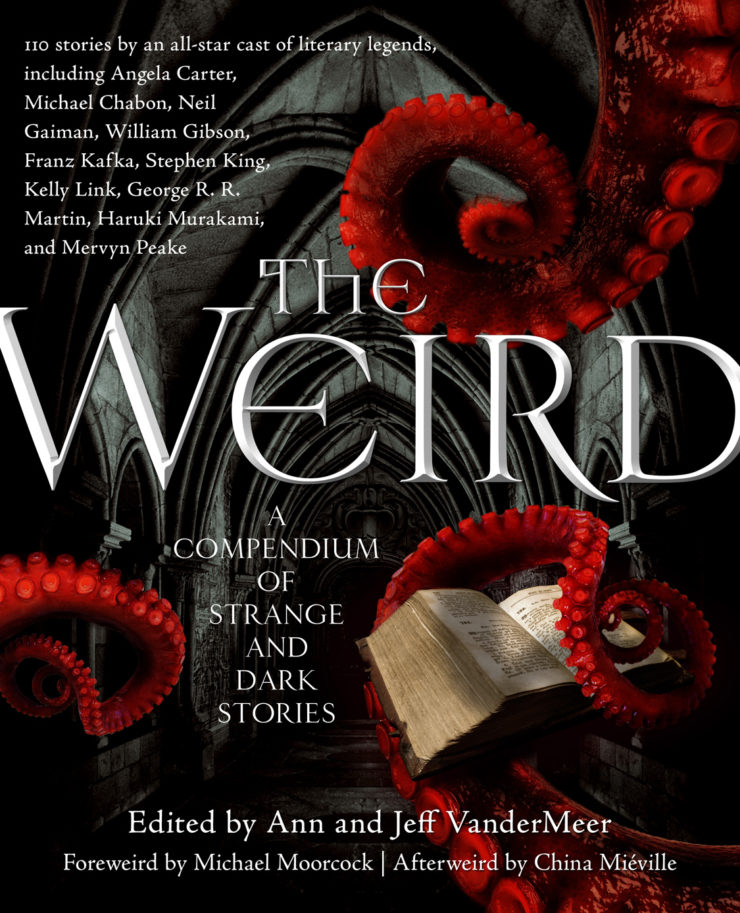

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Rodoreda, writing from the in-between space on the other side of Lovecraft’s feared fall, comes down on the lack-of-meaning side of this prism: Narrator seems moved without agency by furious mobs, by the man who backs her against a tree and the unearned desire he invokes anyway, by her own body. It reminds me of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, a classic of Latin American magical realism I hated in high school and haven’t yet matured sufficiently to appreciate. I acknowledge this to be entirely a failing on my part, a huge chunk of world literature that frustrates me solely because of my own cultural preference for stories driven by characters with agency. This is not only an American thing, but a Jewish thing—our weirds tend to be fantasies of exaggerated agency, of sages and fools who make things happen even beyond their original intents. I’m glad that so many readers who share my formative stories can also appreciate other fragments of the kaleidoscope, and maybe I’ll figure out how to do that by the time I’m 50 or 60; I’m not there yet.

I am intrigued, though, by the places where the oppressed weird intersects with the privileged weird. Lovecraft admired “men of action,” but only sometimes managed to write them. More often, his narrators are tugged into action by their inability to resist the drive of curiosity and of attraction-repulsion. They don’t really choose to face their revelations, any more than they make the choice to flee when fear finally overcomes the desire to know.

And often, like the narrator of “Salamander,” part of this lack of choice comes from their own natures. I’m reminded particularly of “The Outsider,” who yearns for human contact only to be rejected for his monstrosity. The outsider, though, eventually finds a happy ending in the company of those who also live outside—much like Pickman, much like the narrator of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.” Salamander just gets a trio of eels, stealing the last remnants of her humanity for their play. It’s a bleak and compelling image, but it mostly makes me want to put in a call to Nitocris and tell her to hurry up and introduce this poor lizard to a more welcoming monstrous community.

Next week, a different take on alienation and rejection in Priya Sharma’s “Fabulous Beasts,” which first appeared here on Tor.com and is now part of the author’s Shirley-Jackson-nominated short story collection.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.