I hold a special fondness for poems and stories that bridge oral tradition and literature. I think it was in that switch, from oral to written, that fantasy as a literary form was born. Such works—the Panchatantra, Epic of Gilgamesh, Odyssey and the Mabinogion to name a few—are the ancestors of contemporary fantasy. The Kalevala is another such bridge.

I would not be surprised if among the erudite readership of this website there are those who have studied The Kalevala at great length. If you’re out there, please chime in. I’m just a casual reader struck by the scope, adventure, humor and emotion of the work. I would never have even heard of it if not for reading somewhere that Tolkien loved it. Now that I’ve read it I regard The Kalevala as one of the most engaging epic poems I’ve ever read, en par with Ovid’s Metamorphosis, though less complicated.

If you aren’t familiar with The Kalevala, I’ll provide a little background. The Kalevala transitioned from oral to written much more recently than the others I just mentioned. In the early 19th century, a Finnish doctor named Elias Lonnröt compiled folksongs into a single epic poem, and revised it over the course of many years and numerous trips to the countryside, first publishing it in 1835. We think of The Kalevala as Finnish, but more accurately the work comes from the region of Karelia, which has at various times fallen under the control of Sweden, Russia and Finland. (Anyone better versed in the politics of Karelia will know that is a very simple way of explaining it, and I admit I may be misinterpreting the history).

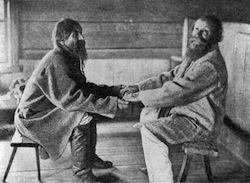

The stories in The Kalevala were—and still are—sung with a particular tune, and sometimes a zither called a Kantele accompanies. Singers would sit across from each other, fingers intertwined, singing sometimes in unison, sometimes call-and-response. Singing is also one of two methods of magic in The Kalevala, the other being a sort of built-in elemental, natural magic (generally used by female characters). Sorcerers sing magic. Isn’t that cool? At least, it’s consistent with the inherent meaning of the word enchantment. Oh, and another cool detail: Longfellow used the rhythm of The Kalevala for Hiawatha.

Singing the runot, the songs, often became a profession for the blind. In fact, when Lonnröt compiled the runot from oral tradition, blind singers contributed the vast majority.

The stories themselves are generally distinct from other major cycles of mythology but now and then a familiar element pops up: a little Osiris here, a little Tiamat there, and a transition from pagan imagery to Christian at the end (clearly a late addition to the tales). The larger plotlines center on the exploits of three men: Väinämöinen, a powerful though not entirely pleasant wizard; Lemminkäinen, a brash, two-fisted womanizer; and Illmarinen, a magical smith, who seems to be a generally decent sort of dude. Illmarinen forged the sampo, which is very important. (I have no idea what exactly a sampo is, but it was all the rage in old Karelia. I suspect it’s what was glowing in the suitcase in Pulp Fiction. And at the end of Lost In Translation, Bill Murray whispers to Scarlett Johannson what a sampo is. It’s probably the name of the child empress in The Neverending Story.)

The stories themselves are generally distinct from other major cycles of mythology but now and then a familiar element pops up: a little Osiris here, a little Tiamat there, and a transition from pagan imagery to Christian at the end (clearly a late addition to the tales). The larger plotlines center on the exploits of three men: Väinämöinen, a powerful though not entirely pleasant wizard; Lemminkäinen, a brash, two-fisted womanizer; and Illmarinen, a magical smith, who seems to be a generally decent sort of dude. Illmarinen forged the sampo, which is very important. (I have no idea what exactly a sampo is, but it was all the rage in old Karelia. I suspect it’s what was glowing in the suitcase in Pulp Fiction. And at the end of Lost In Translation, Bill Murray whispers to Scarlett Johannson what a sampo is. It’s probably the name of the child empress in The Neverending Story.)

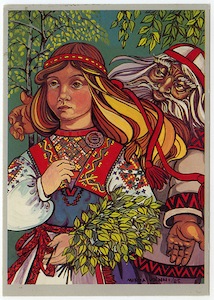

This focus on male characters does not mean, however, that women are not important in The Kalevala. Far, far from it. Consistently, the most moving and enchanting portions relate to female characters. I guess you could say the male characters get a lot of the big, cinematic scenes but the heart of The Kalevala is in the emotional narratives of the women.

When first we meet Väinämöinen, the great magical being, we know full well he’s extraordinary before he has actually done anything. Why? Because first we learn of his mother, Ilmatar, and her amazing conception and pregnancy. A spirit of the air, impregnated by the sea, she swells and swells, well past human dimensions, and remains pregnant for more than seven centuries. When at last her son, Väinämöinen, emerges from her divine, elemental womb, he’s already ancient and venerable. Obviously, with an introduction like that, the reader knows this guy is big magic.

I’m not going to summarize the entire story, but I would like to focus on a section in the beginning.

Väinämöinen fights a singing duel with an impetuous and unwise youngster named Joukahainen. The noob gets pwned, or words to that effect. Specifically, Väinämöinen turns Joukahainen into a swamp. I like that. You know your ass is done for when you are magically pimp-slapped into a swamp. And, as he’s got all the merit of a thrift store douchebag, Joukahainen goes, “Wow, you kicked my ass in magic singing. Please unswampify me and you can marry my sister.”

Väinämöinen, not the most compassionate guy, goes, “Yay, I won a lady!”

Handing women off like prizes is both despicable and commonplace in mythology (and not just there). But here the story goes into the emotional reaction of the promised bride, Aino, who quite clearly would rather die than be handed off like auctioned cattle. She cries, and her family members ask her one after another why she’s so sad to be promised to the wizard. Her grief builds as they ask, and her full answer is such beautifully expressed anguish I had to put the book down a few times and sigh, tears in my eyes. (Note: The Oxford World’s Classics edition translated for meaning but not rhythm, so this doesn’t match the actual tune of the runot.)

Here is the concluding portion:

“My mood no better than tar

my heart no whiter than coal.

Better it would be for me

and better it would have been

had I not been born, not grown

not sprung into full size

in these evil days

in this joyless world.

Had I died a six-night old

and been lost as an eight-night-old

I would not have needed much—

a span of linen

a tiny field edge

a few tears from my mother

still fewer from my father

not even a few from my brother.”

Soon after, she drowns herself rather than marry Väinämöinen (that’s not the end of her story but I don’t want to give everything away). For all the amazing magic and adventure of The Kalevala, the tragedy of Aino is the part I think of the most. Without this heart-rending story The Kalevala would be unbalanced, focused on action more than consequence, overpowered by characters like Lemminkäinen, who basically thinks with his southern brain.

Soon after, she drowns herself rather than marry Väinämöinen (that’s not the end of her story but I don’t want to give everything away). For all the amazing magic and adventure of The Kalevala, the tragedy of Aino is the part I think of the most. Without this heart-rending story The Kalevala would be unbalanced, focused on action more than consequence, overpowered by characters like Lemminkäinen, who basically thinks with his southern brain.

There’s a lot more that I could say. There are enormous birds, magical woodsmen, witches, a proto-Frankenstein resurrection, really tough elk, tricky wasps, a sampo—whatever the hell that is—a ton of spells, love, war and revenge. Rich, wonderful fantastical and imaginative throughout. But, in the immortal phrasing of LeVar Burton, “You don’t have to take my word for it.”

Jason Henninger works in Santa Monica, CA, and does not own a sampo.