There was a time, not that long ago, when if you told people you were a science fiction fan they would ask you—no doubt thinking of The X-Files—whether you really believed in aliens. My usual response was to reply, putting a gentle emphasis on the second word, that it’s called science fiction for a reason. But the fact is that I did, and do, believe in aliens … but not in that way.

I do believe that there are intelligent alien species out there in the universe somewhere (though the Fermi Paradox is troubling, and the more I learn about the peculiar twists and turns that the evolution of life on this planet has taken to get to this point the more I wonder if we might, indeed, be alone in the universe), but I don’t believe that they have visited Earth, at least not in noticeable numbers or in recent history. But I do believe in aliens as people—as complex beings with knowable, if not immediately comprehensible, motives, who can be as good and bad as we can, and not just monsters who want to eat us or steal our water or our breeding stock. And I can date this belief to a specific book.

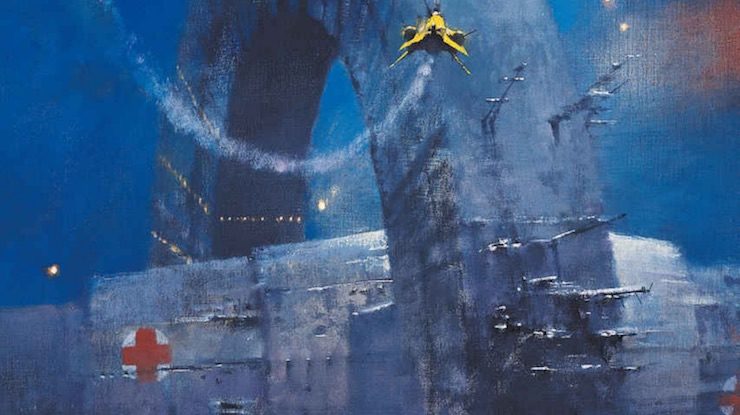

I was twelve or thirteen when my older cousin Bill came from California to live with us for a summer. At one point during his stay he had a box of old paperbacks to get rid of, and he offered me my choice before taking them to the used book store. One of the books I snagged that day was Hospital Station by James White. It was the cover that grabbed me, I think: a realistic painting of a space hospital—a clear ripoff of Discovery from 2001, but adorned with red crosses. The concept of a hospital in space promised drama, excitement, and tension, and the book did not disappoint. But better than that, it changed my mind and my life in some important ways.

Up until that time I had generally encountered aliens only as villains, or even monsters—the Metaluna Mutants from This Island Earth, the hideous creatures from Invasion of the Saucer-Men, the Martians from War of the Worlds, The Blob. True, there was Spock, but he scarcely seemed alien, and besides there was only one of him. Even in prose fiction (I had recently read Ringworld) the aliens were more nuanced, but still fundamentally adversarial to humanity; alien species tended to appear as stand-ins for either thematic concepts or for other nations or races of humans. But in Hospital Station, for the first time, I found aliens who were truly alien—strange and very different—but nonetheless allies, co-workers, and friends.

Hospital Station is a collection of five stories showing the construction and evolution of the eponymous station—Sector Twelve General Hospital—in a universe with so many intelligent species that a standard four-letter code has been developed to quickly categorize their physiology, behavior, and environmental needs. To accommodate those widely varying environmental needs, the station is divided into many sections, each with atmosphere, gravity, and temperature suitable for its usual occupants. A universal translator ameliorates the problems of communication between species, but—and this is critical—it is not perfect, nor can it immediately comprehend the languages of new aliens; it must be brought up to speed when a new species is encountered. Also, eliminating the language problem doesn’t prevent miscommunications and cultural conflicts.

Buy the Book

Beginning Operations

But despite the conflicts that do exist between species in this universe, the primary problems that face the characters in Hospital Station are those that face any doctors in any hospital on Earth: healing the sick, solving medical mysteries, and preventing the spread of disease. The conflicts are interpersonal, the villains are diseases or physical processes, and the tension is generally provided by a race to heal or cure in time rather than a need to destroy or prevent destruction. It’s not that there is no war in this universe, but the army—the interspecies Monitor Corps—is barely seen in this volume and exists primarily to prevent war rather than to wage it. It is a fundamentally optimistic universe in which the main characters, of widely diverse species with different needs, personalities, and priorities, are primarily cooperating to solve problems rather than competing against one another.

This was the first time I had encountered this type of aliens and I devoured the book with gusto. Even better, I discovered it was the first in a series, which continued until 1999. I soon learned that many other such fictional universes existed—including, to some extent, later incarnations of Star Trek—and eventually I began writing about them myself. The Martians and Venusians in my Arabella Ashby books are intended to be people who, though their bodies, language, and culture may be different from ours, are worth getting to know.

The stories in Hospital Station were written between 1957 and 1960, and they may seem rather quaint by today’s standards (the portrayal of women is particularly eyeroll-worthy). But it served to introduce to me a concept which we now summarize as “diversity”—the importance of representing and accommodating different kinds of people, with different points of view, who can by their very differences improve everyone’s lives by bringing their unique perspectives to bear on our common problems. Unlike the purely villainous aliens of Invasion of the Body Snatchers or The Thing, these aliens are complex beings, and even when we disagree we can work together to find common cause. And though this view of diversity can sometimes seem facile and overly optimistic, I think it’s better to hope for the best than to live in fear of the worst.

Originally published July 2017 as part of The One Book series.

David D. Levine is the author of Andre Norton Nebula Award winning novel Arabella of Mars, sequels Arabella and the Battle of Venus and Arabella the Traitor of Mars, and over fifty SF and fantasy stories. His story “Tk’Tk’Tk” won the Hugo, and he has been shortlisted for awards including the Hugo, Nebula, Campbell, and Sturgeon. Stories have appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, F&SF, Tor.com, numerous Year’s Best anthologies, and his award-winning collection Space Magic. His latest novel is The Kuiper Belt Job.

Given the vastness of the universe, I doubt we’re alone in the universe. But I do think we’re likely alone in the Milky Way galaxy, which for practical purposes is the universe. We’re never going to see or talk to that race off in the middle of the Virgo Supercluster somewhere.

My conventional view has long been that life must almost certainly exist elsewhere in the universe, that intelligent life also exists with almost as much certainly, but that it’s likely so far away we’ll never know for sure, and/or so distinct from us we wouldn’t even recognize it as such if we did encounter it. I was certainly skeptical living beings from other planets had ever visited Earth, and regarded it laughably unlikely aliens just happened to have anthropomorphic forms, as in much of science fiction.

However, lately it seems one of three things must be true:

(1) Beings from another world are visiting our Earth via technology far in advance of anything humans can currently create.

(2) Somewhere, humans have created technology radically more advanced beyond what officially exists, but are keeping it secret, or

(3) The U.S. government, which has confirmed the authenticity of footage of this apparent advanced technology, is trying to convince us it’s real, as in a massive psyop.

I still lean heavily towards (2) or (3) being the case, but am less confident now than than I’ve ever been that (1) is absurd.

But whatever the case, the answer is terrifying. Which brings me to the weirdest aspect of these revelations: the widespread indifference with which they’ve been greeted. How could these asronishing developments, whatever the truth of them turns out to be, fail to be of universal fascination? Are we so jaded by the weirdness of the 21st century that even plausible and officially confirmed reports of radically advanced and possibly alien technology can’t rouse us from apathy? What’s become of our curiosity?

Skallagrimsen—

I think choices 1 and 3 are the most likely. Choice 2 is improbable, because it would mean the entire scientific community has somehow fallen centuries behind some mysterious group of Tony Stark figures. I can more easily believe in the government telling massive lies or aliens far more advanced than we are with obscure motives.

As for people being incurious, that’s normal. People are quite capable of ignoring disturbing notions when the evidence is right in front of their face.

If you want an early portrayal of non-villainous aliens, you should try “Forbidden Planet”, described by the late Arthur C Clarke, as “one of the three or four science-fiction films it is possible to refer to without embarrassment”. The Krell, who we never actually see, are portrayed as a civilized race, destroyed – ironically – by their failure to comprehend the darker side of their minds – “Monsters from the Id!”. As Clarke suggests, the fact that the film was based on a plot idea by a certain William Shakespeare may have helped.

@donald, you might be right, although “centuries behind” seems conjectural. Perhaps it’s mere decades? In 1850 we were just finally leaving the Age of Sail. In 1950 we had atom bombs, and weren’t far off from landing on the moon. Who’s to say how fast tech might progress after a major theoretical breakthrough?

There is a famous preface by Isaac Asimov where he talks about the two types of Robot stories that were around when he was growing up: the most common, Robot-as-Menace; and the more distinctive, but still rather reductive, Robot-as-Pathos. It slowly dawned on him that he could write stories that were neither, and featured robots as imperfect tools.

I’ve often thought the same applies to aliens, not just in the specifics (e.g. Independence Day is clearly Alien-as-Menace, E.T. is clearly Alien-as-Pathos) but also in the wider sense that both robots and aliens are used in these stories as stand-ins for something else, not allowed to actually be robotic, or alien.

My favourite stories are where the author aims for “Alien-as-Alien” – the point of the aliens is not that they’re good, or bad, but that they’re Different, preferably Really Weirdly Different. Sometimes this is just one element of a larger plot – Ann Leckie’s Ancillary trilogy is largely a thriller in space, but features some aliens which aren’t evil, just so non-human that morality has no meaning.

But it really shines in short-story form, where authors can play with a single idea, without servicing a wider plot. Notably, although described here as a series of books, James White’s Sector General stories are not novels, but loosely linked short stories published individually in magazines, then re-published as collections.

A more recent, and much less humour-driven, example is Mercurio Rivera’s “The Scent of Their Arrival”, told from the point of view of aliens who don’t see the world the same way we do at all.

Stanley Weinbaum wrote some pretty alien aliens (well, Martians) in 1934; as Campbell said “Write me a creature who thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man.” Tweel does that pretty well, all things considered.

@@.-@ No Forbidden Planet isn’t based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. For example, Morbius doesn’t try to wreck and force it down on to Altair 4; unlike Prospero who deliberately brings the ship and those in it to his island. Nor is Morbius in exile from some form of governance of Earth. Again unlike Prospero who spent too much time with his books and was deposed.

The closest Forbidden Planet comes to The Tempest is Morbius and Altaira live in isolation on Altair 4 like Prospero and Miranda on their island. When Cookie gets drunk with Robby like Caliban and a sailor. If Robby is a servant like Caliban was, but behaves like a low-powered Arial. The role of Ariel proper is generated by the Krell machine and behaves basely like Caliban. It is as if Ariel has role swapped with Caliban.

A few people see the superficial resemblances between the play and the film, and think the one is based on the other. No so. When you look closely the connections disappear. Like many untruths, it is securely part of our cultural folklore. Everybody knows them, few if any bother think them through to see if they are valid or not. This one ain’t so.

On the other hand, someone should write a science-fiction novel that is firmly based on the Shakespeare play. Now that would be fun.

2: I suspect that most people believe either 2 or 4. (4 is “this is some footage of a mundane object or phenomenon behaving in a weird way that looks like something impossible, like the time I saw a cow with a bin bag on its horns and thought it was a dinosaur”. )

Highly skilled pilots and other observers have misidentified air and ground targets in inexplicably stupid ways more times than we can count.

Note that the US government have said it’s real only in the sense of “yes, this is an authentic USN video recording” (and i believe them). They’ve taken no position on what it is a recording of.

I read that the non-military nature of White’s Monitor Corps was apparently due to his abhorrence of violence, a product of growing up in Ireland during The Troubles.

Sector General was noted as the the first explicitly pacifist space opera series.

8 seems a bit harsh. A story can be based on another without being a direct one-to-one copy of it.

West Side Story is absolutely definitely based on Romeo and Juliet – the writers did so deliberately from the start – but I don’t think it would meet your criteria for “based on”. Romeo and Mercutio go to Capulet’s ball because Mercutio wants to distract Romeo from his unhappy love affair – Tony goes to the dance because Riff is planning to challenge Bernardo, and he wants Tony along as backup. There’s no Friar Laurence character, no deliberately faked death, and Tony doesn’t kill himself – he’s killed by Chino. Juliet kills herself at the end – sorry, spoilers! – but Maria survives.

I think if the writers of Forbidden Planet said “This film is not in any way based on The Tempest and has nothing to do with it” we’d pretty quickly realise they were being untruthful!

For mostly peacefully coexisting aliens, I think of the Cherryh’s Chanur books.

In response to Skallagrimsen in 2:

I see two options, between them, as most likely:

a) Parts of the US government have developed technology slightly more advanced than what is commonly known. They are trying to conceal these vehicles from the general public and from most of their own military, yet test them and train the crews. The agencies in the know encourage wild speculation by the public, in part through implausible denials and official investigations.

b) A different government has developed technology slightly more advanced than what is commonly known, and operates these vehicles over the United States (and a few other places).The US government is trying to conceal the inability to control US airspace from the general public and most of the military. The agencies in the know encourage wild speculation by the public, in part through implausible denials and official investigations.

I do love that book, very very much. One of the few paperbacks I know I had before 1966, too.

In terms of aliens being people and being friendly, though–Doc Smith’s very first novel, The Skylark of Space, features that in a major way. Published in 1928, written at least a decade earlier than that depending on your sources. Follows through all his work, too, the evil aliens are a rarity (admittedly, the Eddorians are a pretty extreme case of being evil!).

@@@@@ Ajay, you’re right, I’ve considered that possibility and should have included it.

@@@@@o.m., I still lean heavily towards a terrestrial origin, whether it’s unacknowledged technology or some atmospheric illusion. But I’m surprised by how much less dismissive I now feel towards the otherworldly hypothesis than I would have felt a few years ago. If the twenty first century has done anything it’s disrupted my sense of the possible.

@Ajay 10, I’m aware the government hasn’t taken an official position on what the footage is. Maybe it knows, maybe not. Both possibilities are terrifying, or should be.

Alan Dean Foster has lots of non-humans of various sorts in his Humanx Commonwealth stories. Very few people are completely evil, and even the primarily antagonistic species is not evil as such

I’m just wondering whether going from the initial impression (presumably garnered mainly from 1950s U.S. and British SF movies and TV shows) that aliens were primarily villains and monsters to a more “humanistic” view by encountering such materials as James White’s stories was mainly an American experience.

Growing up in Germany, I don’t recall having been subjected to all those monster-of-the-week movies and TV shows as a child. Instead, I was first introduced to the (fictional) possibility of intelligent extraterrestrial life – and to SF in general – mainly by the German Perry Rhodan literary series, which I discovered around the age of 12 in the early 1970s, as well as by Star Trek’s TOS, which first came to German TV (dubbed in German) around that same time. (I had also seen 2001 -A Space Odyssey when it came out, but I was only 8 or 9 years old then and really didn’t understand what the movie was all about, except that it seemed to depict a really cool near-future in which close-orbit space travel would be quite routine.)

Given the great variety of extraterrestrial life in both of those fictional universes, ranging from technologically advanced races – and (in Perry Rhodan) even a benign superintelligence – that helped humanity find its way to the stars, including with the gift of FTL-travel, to menacing aggressors bent on invasion, destruction and subjugation, extraterrestrials to me always appeared as good or bad – or even unknowable – in their motivations and actions as humans could be. There were heroes and villains, but also countless ordinary folks just doing their jobs, both among Terrans as well as the extraterrestrials.

In fact, in the 1960s, the Perry Rhodan series even featured a robot civilization – the Posbis – that flew around in enormous cube-shaped (!) space ships and was hell-bent on destroying all biological life. In the end it turned out that they were the victims of a long-standing technological manipulation by a third party, and once relieved of that manipulation by a plucky team led by our titular hero, they subsequently became one of Terra’s closest allies.

So anyway, to me in my youth, and especially during the “golden years” of my acculturation as a fan of SF, the possibility of extraterrestrial life was never so much a source of repulsion and horror but rather of great interest and fascination, and even hope, right from the start.

Thus, similar to David Levine, as a kid I too came to “believe in aliens as people—as complex beings with knowable, if not immediately comprehensible, motives, who can be as good and bad as we can….”

However, for me this was not preceded by a phase in which I was under the impression that aliens were “just monsters who want to eat us or steal our water or our breeding stock.” That actualIy came later, I suppose, through such movies as Alien and its sequels, as well as after-the-fact exposure to those American and British “classics” from the 1950s and 1960s featuring Nazis and communists “monsters” from outer space and the like. However, by that time I was old enough to understand their metaphorical nature.

@20 (unpublished)–there’s really no call to dismiss or respond rudely to other commenters, and this is not the first time you’ve done so. Please consider this a final warning–review our moderation policy, and engage in a civil manner going forward. Thank you.