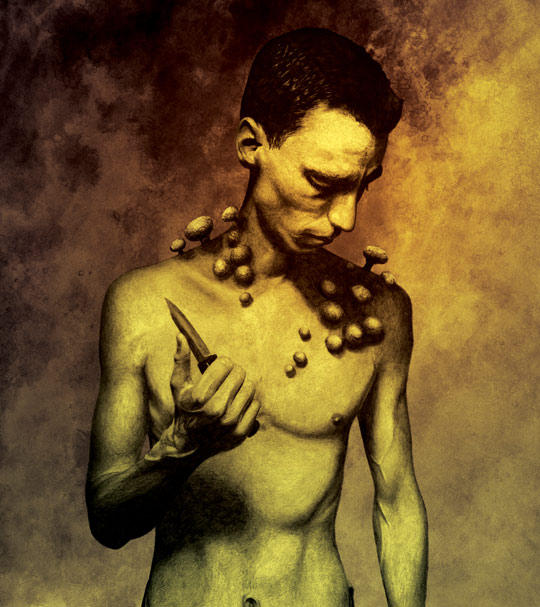

George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards multi-author shared-world universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years. Now, in addition to overseeing the ongoing publication of new Wild Cards books (like 2011’s Fort Freak), Martin is also commissioning and editing new Wild Cards stories for publication on Tor.com. In Cherie Priest’s “The Button Man and the Murder Tree,” it’s Chicago in 1971, and Raul is a button man—a professional ender of lives that the Mob needs ended. But something’s odd about his most recent assignments. And then there are those mushrooms growing out of his skin….

This short story was acquired and edited for Tor.com by George R. R. Martin.

Chicago, 1971

Sammy Ricca poured himself a slug the color of old honey, spilling hardly any of it. He lifted the glass to his mouth, and the cheap whiskey rippled as he tapped it with his upper lip, pretending to drink it. He peered through the blurry amber at a tall, lean shadow in a gray suit, and he said, “I heard they were using that old tree again. Word’s getting around.”

“That was the idea,” the button man murmured. And then, “You may as well drink that.”

Sammy threw back a mouthful, as suggested. He shifted his ass so he could sit on the edge of his desk. A pen cracked under his weight, and dark blue ink pooled beneath his thigh. “This isn’t about Angelo.”

“I already know about Angelo.”

“I could tell you—”

“Everything you know, you sang already.” Beside Sammy’s swiftly staining leg sat an ugly Lucite ashtray. It was emblazoned with the logo of a bar that’d burned down years ago. The button man sighed, and wished he had a cigarette.

“Raul, the money wasn’t—”

“I know.”

“I don’t think you do. Before me it was Dragna, and before him, Carlo. What we had in common, it wasn’t just our names on the Murder Tree, it—”

“The Deadman’s Tree. Subtle difference, there.” He withdrew a Colt 45, checked it, and tried not to hear how hard Sammy swallowed. “And it doesn’t matter now, after the mess you made of things.”

“No, I didn’t make a mess. It’s not Angelo. It’s not the money.”

“And it’s not up to me.”

The button man might’ve said more, but a warm, prickling sensation began a slow swell around his wrists. His shirt cuffs tightened. His collar was the same damn story. He wished he weren’t wearing a tie. He wished it wasn’t so warm in the small, gray office with the creaking fan and the window that couldn’t open far enough to let Lake Michigan breathe inside.

With his free hand, he tugged at the knot that pressed uncomfortably against his throat. It was his turn to swallow hard.

“Hey Raul is . . . is something wrong?” Sammy stalled.

He hesitated. He hadn’t told anyone, which didn’t mean nobody knew.

“Raul?”

“No. Nothing’s wrong.” His wrists felt puffy. His left hand hurt from the pressure, from the lost circulation. In another minute, it’d be numb except for the pins and needles if he didn’t get those cuffs unbuttoned. He lifted the Colt and aimed it between Sammy’s eyes.

Sammy drank his last drops fast and hard, like he didn’t even taste them. He slammed the glass down on the desk. Then, as the Colt twitched, ready to fire, he squawked, “Wait—just wait a minute, please? One last request.”

Raul’s hands burned. They were swollen and marbled, white and red. “Make it fast.”

“Don’t dump me in the lake, would you? Leave me here, or stick me in the street.”

?“What do you care?”

“Elaine and the kids. It’ll be easier on them, for the life insurance. Leave them something to bury. I’m asking you—in case you got family I don’t know about. Promise me that, and do what you gotta.”

“All right, I promise.”

“And I need to tell you . . .” Sammy’s voice sped up, desperate for these last seconds. “You don’t even know why you’re really here—”

Raul pulled the trigger twice. Sammy Ricca fell back across the desk and tumbled to the floor. A small curl of smoke escaped his forehead.

Raul checked the clock on Sammy’s desk. The cleaners wouldn’t come around for another twenty minutes.

He could’ve broken his promise if he’d wanted, but it felt like bad form, and anyway, it wasn’t Elaine’s fault that her husband thought he was smarter than Moe Shapiro and Angelo Licata. So the button man picked up Sammy’s corpse, taking care to avoid the long streaks of ink and the sliding drips of blood.

He left it in the alley behind the newspaper, just behind the advertising division, where Sammy’s shattered skull would make quite an impression on the first bum to come by for a piss. And while Sammy lay there, mucking up the pavement with his brains, the button man fought the urge to tear off his jacket and rip at his shirt cuffs, then his tie, at anything he could loosen or adjust. One thing after another, in any order that would let his skin breathe free.

But no. Not here.

Instead, he stumbled out of the alley and ducked into the onrushing glare of a car’s headlamps, then out of it again. Keeping to the sidewalk only briefly, he found another dark spot between two buildings and he could’ve cried with relief. He knew this place—this was the back end of a restaurant Angelo liked, and the cooks kept their mouths shut unless they were taste-testing the specials. It’d do in a pinch and thank God for that, because tonight’s pinch was about to strangle him.

The back door was hollow and it rang like a metal gong when he knocked. It cracked open and a round face covered in steam or grease looked at him with confusion, concern, and then the careful blankness of a man who knows when to pretend he doesn’t know a goddamn thing.

“Mr. Esposito,” he said. “How can we help you tonight?”

“I need a minute inside.”

The door opened wide enough to let him in to a world of bright steel pots and simmering gas stoves. He dodged big-breasted waitresses with damp, round trays and kept his head down when the men at the ovens shouted back and forth in Italian or some second-generation’s pidgin.

Whoever’d let him in didn’t ask for details and didn’t follow him back to the bathroom the staff used, a big gray box with one fizzing, swaying light bulb dangling on a wire. Raul shut the door, locked it, and leaned forward on his hands, staring down into the sink.

The taps were the old-fashioned sort: one for hot and one for cold, but shit-out-of-luck if you wanted lukewarm. He twisted both faucets on, letting the hot side steam and the cold side swirl, all of it making a friendly white noise to thwart any curious ears that might be dumb enough to come close.

Above the sink was a smudged rectangle of glass that passed for a mirror.

The button man met his own eyes as he pulled off his suit jacket and hung it on a hook that might’ve held meat as easily as towels. His shirt came off next, though his hands trembled as he fed the slim white buttons through the holes, one at a time, until the cotton parted with a soft, sticky sound. He knew better than to look down. He didn’t want to see that he’d ruined another Van Heusen. Didn’t want to look at what was growing there on his chest, not just his wrists and neck.

He stripped to the waist.

Beside the toilet squatted a knee-high trash can. He picked it up and set it on the sink’s edge, then reached inside his limp jacket for the inner pocket, and pulled out a switchblade. As quickly as he dared, he sliced the bubbling lesions away.

He started at his wrists, since those growths had blossomed first, and were largest. He pruned them one by one, scraping the blade along the clustered stalks. They popped free and dropped into the steel waste bin with a spongy little ping that made his teeth itch. Some as small as his pinky nail. Some the size of his thumb. Brown-capped or gray, with creamy undersides and speckles.

Perfect, round mushrooms. Dozens of them. Hundreds, maybe—if he gave them another hour in the dark, and the sun wouldn’t be up for another six hours if he was lucky.

They were less trouble from dawn ’til dusk, and less prolific when he kept his skin dry. That much Raul knew. He was still learning what worked and what didn’t, but the truth was more horrible every day: He couldn’t stop them. He couldn’t manage them. He could only hide them.

He’d drawn a card, and it’d turned. Simple as a noose.

Another flick of the switchblade and another half-dozen smaller chunks of fungus fell into the bin.

It didn’t hurt. Once he’d gotten over the sheer gruesomeness of it all, it was almost easy. A bit of unfamiliar pressure. A moment of disconnect, and the chilly sense that he might be bleeding—but wasn’t. He couldn’t carve the things free, but a simple scrape would temporarily excise them. It wasn’t altogether different from trimming his nails or blowing his nose—not in principle, and that’s what he told himself as he methodically filled the bin and wondered what he was going to do with the damn things. Flush them down the toilet? Cover them with paper towels, and pray nobody noticed?

He laughed, a grim grunt that didn’t hold a drop of humor.

I could leave them in the kitchen.

Stick them on the pizzas, or in the carbonara. Garnish a salad, or what have you.

One more. Beside his belly button, growing almost while he watched. He picked it off with the blade and absently rubbed his thumb against the round, white patch of skin it’d left on his stomach. He tumbled this last tiny cap between his fingers and brought it up to his nose. It smelled like nighttime, like mulch and butter.

Quickly, before he could talk himself out of it, he popped the cap into his mouth and chewed.

It squished between his teeth like any other mushroom might, its texture firm but loamy, its flavor familiar but specific. He swallowed.

He knew the right mushrooms could give you visions—and the wrong ones could kill you, and he didn’t know what his own personal brand might do. He felt a fast pang of fear, but it went its merry way when he told himself, No way. It came from the outside. Won’t hurt the inside. And maybe he didn’t believe that, but it kept him from sticking his finger down his throat and asking for a recount.

A knock on the bathroom door almost sent him out of his skin.

“What?” he barked, anxiously squeezing the trash can.

A timid voice on the other side said, “Mr. Esposito, sir? Are you all right in there?”

“Yeah.”

“It’s been . . .”

Half an hour probably. “I know. I’ll be out in a minute.”

He glanced around the naked little room and would’ve given his right arm for an incinerator chute, but the toilet would have to suffice. He took two handfuls of the mushrooms and dropped them into the bowl. The first flush took them away with a sweeping swirl, and while he waited for the tank to refill, he wondered what the hell he was going to do.

Ten minutes later he turned off the faucet. Redressed, if somewhat hastily, he exited through the kitchen door, and he didn’t say a word to anybody.

Outside he heard sirens, so someone had found Sammy and called it in before the cleaners found him. Good. Get that life insurance policy rolling, why don’t you. Raul’s business there was finished and really, he should’ve been long gone—but he wasn’t, and he wasn’t sure where he wanted to go. Home was better than no place, but he was restless and itchy, and he wanted to walk. So he walked.

He took a rambling path through Little Italy, trusting the El to pick him up when he did eventually feel like riding. Just this once, the lake smelled clean when the wind rolled off it, sweeping through the brick jungles that would never burn again, cow or no cow; and it was probably his imagination, because the lake always smelled like cold decay and dirty sand. Maybe it just smelled better than mushrooms and blood, or sweat and the kitchen of a second-rate Italian place where people went to talk more than they went to eat.

The button man wasn’t entirely sure where he was headed. It didn’t dawn on him until he was right there at the clearing where the old park used to be, back when anybody gave enough of a shit about the 19th Ward to give it a park. He’d made a beeline for it without even thinking about it.

The Murder Tree. No, the Deadman’s Tree.

The tree was a legacy case, and like Sammy’d said—some of his very last words—it’d been a long time since it’d been a well-used spot, but Ed Galante thought it’d be a good thing to revive. Ed liked symbols. So here was a bloody tree in a bloody ward, a leftover from when the Irish and Italians’d had it out decades ago.

For a long time, it was just an ancient poplar where kids told stories, scaring one another out of nickels and sleep. And now the gnarled branches and massive trunk were back in service, this looming giant with bark half-bare from fall’s incoming wind.

That tree, it was better than the classifieds, Moe Shapiro once said. Gives people time to get their affairs together. Gives them a last chance to make things right if they can, or if they want to. Not that anyone ever does.

If he’d had a pen, Raul would’ve scratched out Sammy’s name. He didn’t. He left it there, barely legible on the thick paper that’d been nailed in place. It was too dark to see anything but the shape of the letters scrawled against the bone-white sheet, and when he looked closer, he saw something else beneath it.

A new name. He stepped closer, squinting against what must be midnight, by now.

“Harriet O’Dwyer.” So it was still up to the Italians and Irish after all. “The more things change,” he muttered.

But why Harriet?

He played out the possibilities as he walked away from the tree, wandering toward the nearest El stop. She was a piece of work, and she worked half the men in the syndicate. Did somebody tell her something she shouldn’t have heard? Unfortunate, if so. But not unfair. She knew who she was getting into bed with, and recently that’d been a guy named Jake Corallo, if Raul recalled the rumor correctly. Jake’s name hadn’t gone up on the Murder Tree because he’d been shut down last month, before Ed had started up that old tradition again.

Yeah, it probably had something to do with Jake.

He didn’t think about it too hard. It was easier not to. He turned on his heel and went back the way he came, but he didn’t get far before he heard someone call his name. His instinct said this was a bad thing—that he didn’t want to be called out on the street; but his second thoughts told him to lighten up, because it was something that happened to normal people. Something normal people didn’t freak out about, because normal people don’t kill for money. Normal people don’t have mushrooms growing out of their skin.

He froze in his steps and then looked around. His eyes snagged on a guy named Benny Lerch, on the other sidewalk. He crossed the street in a handful of long strides for a man with legs so short. “Haven’t seen you since you left for Philly last year.”

“Has it been that long?”

“And then some, maybe.” He grabbed Raul’s hand to give it a hearty shake. “I heard you went off to New York.”

“Naw, that never happened,” Raul told him.

“Hey, let me buy you a drink.”

“I don’t need a . . . you know what? All right. I could use a drink.”

Raul should’ve told him no, but he didn’t, so he got a drink with Benny Lerch at the Waystation. His mushrooms weren’t growing back too hard yet, and maybe he’d get lucky. Maybe they’d stay gone a few hours.

His clothes were a little dirty with fungal streaks, but it was dark and Benny either didn’t notice or didn’t say anything.

Benny was disposable, and he knew it. That was his strong suit, if he had one.

He’d weaseled into the Syndicate by starting cars when he was a boy; he grew up around big men with big wallets, and he wanted to be just like ’em. Just as well for him it’d never happened. It was probably why he was still alive. That, and the way car bombs had fallen out of fashion before he reached puberty.

Benny was a fat guy, and if he were any shorter you would’ve said he was a fat little guy, but he wasn’t, so you didn’t. He dressed well, if cheaply, and with an excessive fondness for brown. A shaggy comb-over wasn’t doing him any favors, except that it reminded almost everyone that he was harmless. It reminded Raul that none of them were kids anymore.

Benny knew better than to ask any questions about why the button man needed a drink, and he should’ve known better than to gossip, but he didn’t. Over mediocre gin, he said quietly, “It’s weird, ain’t it? How the score’s gone up. Not just since the Deadman’s Tree went back into play—but before that, too. The last couple of months, I mean. Seems like every other night, someone’s out of the game. Bunch of people I wouldn’t expect to see go. People who didn’t seem to be no threat. Not even players, some of them. But I don’t know. Nobody tells me shit, Raul. Nobody tells me shit.”

“So you’ve seen the Murder Tree.” Raul didn’t meet his eyes.

“Saw it, yeah. I saw it.”

“Tonight?”

Benny hesitated, then nodded. “Yeah. They put Harriet up there, huh?”

“Apparently.”

“You ever actually see anybody post the messages?” Benny asked.

“No. I don’t watch the tree. Probably better for my health that I don’t.”

“I’ll drink to that.” He did, raising a glass covered in fingerprints and clinking it against Raul’s. “You uh . . . you think you’ll get the call? On Harriet, I mean?”

“I might.” He almost certainly would, a fact he hadn’t admitted to himself until just then. Must’ve been the gin making him honest.

“You going to be okay with that?”

He shrugged. “Nothing much happened, and what did happen, happened years ago.”

“Yeah, but it happened. So if you do get the gig,” he pressed, “can you do it?”

Raul put his glass down on a wet cardboard coaster. “More easily than I can avoid it.” And that was the truest thing the gin had said yet. “Listen Benny, it’s been good to see you, but I need to call it a night. In case the phone rings in the morning, you know. Our old pal Moe, he’s an early riser.”

“All right man, that’s all right. Good to see you, Raul. Always good to see you.”

On the way home, sitting on the El and watching the city lights streak past, Raul thought about calling Moe tonight and getting it over with. He couldn’t ask too many questions or make too many demands—no, not even him—but he and Moe were tight enough that he could risk a query or two. Of course, Moe might not know the particulars. Galante sometimes played it close to the chest—closer than the old boys, who’d known Moe better and knew how far they could trust him.

So he didn’t call. Besides, like he’d told Benny: Moe was an early riser. Early risers tend to be cranky when their phones ring at 2:00 a.m.

And later that morning, Raul awoke to a ring that summoned him to Moe Shapiro’s office.

Moe’s office was in a nice building on a nice side of the city. Not too flashy—that wasn’t his style. Tasteful and full of books, like a lawyer or a head-shrinker, except Moe’d actually read them all. Once over drinks, he’d told Raul that when he was a kid, his fellow upstart gangsters made fun of him for having a library card. He laughed it off, and kept on reading, and now he sat on top of a big pile of money—the last man left of the old guard. He’d been in the racket since the twenties, when he was one of the new guys who’d taken the game away from the big guys with narrow visions.

Behind his back, people called him “Shorty” or “Specs,” and he didn’t care. He was short and he wore glasses. He knew it as well as anybody. You could rib him if you liked, so long as you kept it friendly and left out anything about him being a Jew. He knew that too, obviously. But he’d be damned if he’d let anybody use it against him.

“What can I do for you, Moe?”

A brunette secretary hustled out of the way and left the two men alone together. The door closed behind her with a click. The button man took off his hat. Moe Shapiro gestured at a stuffed leather chair. “Thanks for coming, Raul. Can I get you a drink?”

“No thanks.”

Moe poured out a dollop for himself, something much nicer than what Sammy’d last sipped, decanting it from a big crystal jug into a matching glass. While he worked, Raul pulled out a cigarette and lit it off a pack of matches he’d picked up at a hotel in Phoenix. “I heard the news about Ricca,” Moe said as he slid a brown ashtray toward his companion’s elbow. It wasn’t as nice as the glass because Moe didn’t smoke.

“Shame about that.”

“Always is. I heard they picked him up in an alley.”

“That’s right,” the button man said. And before Moe could ask, he added, “He had a wife and kids. Life insurance, you know how it is.”

Moe nodded, but it was sometimes hard to read him. “You think Elaine knew what he was up to?”

“No. That’s why Sammy didn’t take a bath.” He concentrated on the cigarette. He waited for Moe to decide how he felt about the small shift in plans.

Finally he said, “It’s a good thing I know you’re not a soft touch.”

All right. Then he wasn’t mad, and Raul was reassured. “So is this the part where you tell me I’m responsible for Legs O’Dwyer? I saw her name on the Deadman’s Tree. A soft touch might say no to that one.”

Moe shook his head, not denying anything. “A soft touch or an old flame, but if we crossed all those names off a list she’d live to see a hundred. All the same, I wish she wasn’t posted. I tried to give her room after Jake bit it; I told Galante to leave her alone, let her cry it out. I gave her a talking to, a chance to pull herself together.”

“Then you played fair.”

“I still don’t like doing it, and I’m not sure why Ed’s insisting. Something about her keeping books for Jake’s operation, and how she doesn’t get to walk away just because she’s sad. But I didn’t know she had anything to do with the books.”

“Me either, but I guess it’s none of my business,” the button man said, and not for the first time.

Moe parked himself behind the desk with a sigh. He left his drink by the decanter, all but forgotten. For half a minute he stared into space, just past Raul’s right ear. For that same half a minute, Raul let his cigarette ash creep toward his fingers without taking a drag.

Moe shook his head again. “And there’s something else I’ve been meaning to ask you.”

“Fire away.”

“It’s about mushrooms.”

The button man nearly gagged on smoke he hadn’t yet drawn. He forced his eyes to flatten, his mouth to set in a neutral line. “Good on pizza. Better with pasta. Best on meat. Otherwise, what about them?”

“Coincidence, is all. Your last two gigs. The cleaners are talking.”

“About mushrooms? At my gigs?”

“You’re not leaving calling cards, are you?”

“You accusing me of junior-league shit?”

“I’m asking, is all.”

“Then no. I don’t leave calling cards. Mushrooms, or any other kind.”

“No need to snap about it.”

Raul said, “Sorry,” but he said it curtly. Better to sound offended than terrified. Better to act touchy than sick.

“No, no.” Moe waved his concerns away with the smoke that crept in his direction. “I didn’t mean to yank your chain. But you know I wouldn’t be doing my job if I didn’t ask.”

“Hey Moe?”

“Yeah?”

“I’ll take care of O’Dwyer.” He changed the subject by force. He stubbed out the barely smoked cigarette and stood. “You think Frank knows where she’s holed up?”

“It’s no secret. She can’t keep quiet long enough to hide, so you never know—she might be glad to see you. Try the boarding house out on Eighth—the one Anne Civella used to run. Call Frank and see if he can get you a room number.” Half to himself, he asked, “What’s that place’s name . . . ? Can’t think of it, off the top of my head.”

“Three Sisters,” Raul supplied. “I know the place.”

“Tonight, if you can swing it. Word down low says she’s got a date with some jackass from the DA’s office in the morning. I’d like for that not to happen.”

Raul put his hat back on and headed home to wait for night.

A stack of newspapers on his dining room table kept him company. He’d collected them over the last few weeks, and clipped articles here and there from rags he found in other cities—knowing what it’d look like if he ever had visitors.

He picked up a recent scrap and read it for the hundredth time.

NO ROOM FOR JOKERS, the headline said, and then went on to editorialize about how the whole breed ought to be rounded up and stuck on an island, like they were all a bunch of fucking lepers. MURDER ON FIFTH STREET, read another lead, and it told the story of two joker kids who’d picked the wrong ice cream shop in which to be a freak. NEW JOKER ORDINANCE, said the next sheet, and it was all about how several city blocks were being deemed “Joker-Free Zones” like they weren’t even people, and never had been.

His wrist twitched. He crumpled the story and let it drop to the floor.

And then there was the expose on Andy Sifakis, the Greek who’d set up shop on the west side. GANGLAND HIT TAKES DOWN JOKER BOSS. That was an exaggeration. Andy hadn’t been a boss, he’d only been new. And a joker. Nothing real bad, not like some of them. Andy’d had antlers, was all—that, and his hands were more like hooves. He kept everything trimmed and filed up real sharp, Raul remembered that from the one time they’d met.

Funny thing was, it wasn’t the Four Families who’d taken Andy to pieces: It’d been the lower goons, guys like the button man and guys even further down the totem pole. But nobody’d stopped them. Word around town said Ed Galante might even be paying for it, and looking the other way. That’s why there weren’t any jokers in the syndicate—at least no jokers anyone knew about. Maybe it was only a matter of time, and maybe times were changing after all. But they hadn’t changed yet.

His conversation with Benny collided uncomfortably with the scraps on the table. Some of those guys weren’t even players. Andy sure as shit hadn’t been.

JOKERTOWN RECEIVES CIVIC IMPROVEMENT GRANT.

And then there was New York City, where the jokers had their own quarter. Their own hospitals, restaurants, apartments. Their own gangs. Their own riots and problems, too. There was always the chance he could trade one set of problems for another, if it came to that. Take the geographic cure, so to speak.

It was something to think about.

Later.

By the time he was finished sifting through the most recent daily rags, the sun was setting low enough that he could take his chances back in the old Bloody Ward, where the Three Sisters boarding house waited at the edge of Little Italy.

The button man took the El and then he took a cab, and then he let himself in through the back door that emptied onto the alley, because no one ever watched it. Some things you could count on. Likewise, he counted on the shifty-eyed maids and working girls who kept their heads down and their lips pursed tightly together, and he turned his face away from them, staying in the shadow of his hat’s brim. He took Frank Ragen’s suggestion and tried the third floor.

Room twenty-one.

The hall was empty and felt abandoned, with its ragged faux-Persian runner and dingy wallpaper that was eighty years old if it was a day. He wrinkled his nose and smelled mostly dust, mostly inefficient cleaning products and the faint, lingering tang of cheap lotion and old tobacco. The room numbers passed in tarnished metal digits, odds on the left and evens on the right. Long before he reached it, Raul knew that twenty-one would be last.

He stopped in front of it, and listened.

Outside, a telephone was ringing in a booth and two cats started up a fight. A drunk complained at a car. Closer, then. Downstairs. Downstairs, the bored teenage boy at the desk was handing out keys and making promises. A vacuum hummed across the floor. Closer still. This hallway, where nothing moved.

This room. And in it, a woman he used to know.

He heard the nearby plop of water dripping onto something that was wet already. The buzz of a radio that couldn’t decide between two stations. Nothing else. No footsteps, no shifting springs in a cheap, battered bed. No furtive phone calls or last-minute sobs.

He put his hand on the doorknob and turned. The knob clicked obligingly. Didn’t have to pick it or kick it down. One of his easier gigs, then, except for all the obvious reasons.

He pushed, and the door leaned inward.

He peered around the frame and saw no surprises within. A bed with an ugly blanket. A dresser no woman would choose for herself. A window overlooking the drug store across the street. She might not be in, or Frank might’ve been wrong. But someone’d been here lately, he could see that much by the discarded stockings and mushed-up cotton balls. The bed wasn’t made, and a smudge of beige makeup marred the right-side pillow.

He let himself inside and closed the door, leaning back against it to make sure it was shut. He slid the cheap metal bolt to lock it, knowing it wouldn’t hold more than a moment if anyone insisted hard enough.

To his right was a bathroom, its door open no wider than two fingers throwing a peace sign. The dripping he’d heard . . . that’s where it came from. A light burned within, casting a slim shadow in reverse. It struck into the lower-lit gloom of the bedroom, a pale yellow line like an arrow.

She was in there. He could feel it in his bones. In his skin, which already crawled with the mushrooms yet to come.

He drew his gun and steadied his breathing. This was old hat. This was the job. She’d known the rules, ignored them, and this was what it cost. He wasn’t the executioner, not her friend, not her lover. Just the messenger. Same as always. No surprises for anyone.

With the back of his free hand, he nudged the bathroom door. It groaned open.

She was in there, all right. And he was surprised.

Harriet O’Dwyer reclined naked in the tub, wrists slashed and body bobbing slowly; that part didn’t bother Raul. He’d had seen plenty of blood and he’d already stepped in hers. He would’ve cursed himself but he didn’t, he only took one step back and wiped his shoe on carpet the color of guacamole. The bathroom was painted with gore, and it looked like more than one woman’s corpse could hold, except that he knew from experience that it wasn’t.

A razor sprawled open on the floor below her dangling, lifeless hand. Obvious as can be, even before he saw the note on the mirror. She’d left it in lipstick, in handwriting barely legible, and when he saw the empty bottle of valium, he knew why.

All it said was “Forget me.”

Not “forgive me.” Not “I’m sorry.” Not even “good-bye.” Raul guessed she had no one to say it to. Just a message for him, because she’d known he was coming. Or if not him personally, someone else she used to know. The odds were pretty good on that one.

He looked at her again. Her hands were scaly and rough. They reminded him of a pair of snakeskin boots he’d bought on a gig in Houston, for laughs. He’d never worn them. Her breasts were scaled too, and when he couldn’t stop himself—he turned her over, her body making scarlet tides and messy splashes as she swayed and sank again—he saw the protrusion from her backside, a foot-long tail that ended in a rattle.

He jerked his hands away, letting her flop back to her original position.

And now he was soaked in bloody water up to the elbows. His knees, his stomach. No escaping it. No graceful, quiet retreat, and no more kidding himself. Legs O’Dwyer was a joker, for Christ’s sake. She’d drawn a card, and it hadn’t been pretty. That card had turned, sometime since Raul’d last seen her.

His thoughts raced to assemble a picture that made sense, and he thought of Jake Corallo who must’ve known, might’ve been the only one who knew. Jake had kept her secret, and now he was gone. No wonder she’d mourned him like that. What else could she do? Hard to play with the big boys anymore when this was what waited under the lingerie.

The button man retreated from the mirror. He turned, and he ran—all the way back down the empty hall, down the stairs, and out the way he’d come because it was always the back door, he was already unwanted and unwelcome. I could’ve talked to her, he thought wildly, the fear and disgust and discomfort stretching into crazy thoughts. We might’ve made some understanding, left together if we both had to go—better than running alone, isn’t it?

And Jesus Christ, it really was time to run. No more pretending, and he’d wasted too much time to prepare so this would go by the seat of his pants and he hated that. It wasn’t like him. It wasn’t how he’d lived this long, and he wouldn’t keep him alive much longer.

Still bloody and wet from that godawful bath, he threw himself into the nearest phone booth and jammed his fist into his pocket. He found some change. Threw it into the slot and dialed once, twice, before he got Moe’s number right.

Moe answered on the first ring. “Shapiro.”

“I need to ask you something, Moe. I need you to tell me the truth.”

The other end of the line was silent, which was a promise of a sort—but not the one he wanted.

Raul continued. “The Murder Tree—I mean, the Deadman’s Tree. The names on it, these last weeks. They had something in common. Something other than what I thought, what I was told.”

“Raul . . .”

“Sammy would’ve blabbed if he’d lived a minute longer, and I didn’t let him. I didn’t have time. But he drew a card, hadn’t he? Nothing obvious, nothing I could see at a glance. But it must’ve been something. You must’ve known.”

Pause. “I’d heard.”

“You’d heard what?” Raul demanded. A few blocks away, a siren wailed to life.

“I’d heard he was hiding an extra face, extra mouths. Extra something, and I didn’t ask for details. But that wasn’t his problem, Raul. A secret like that wouldn’t have put him in the morgue. I talked to Ed. Sammy’d made himself a date with a lawyer, and he was buttoning up. We’ve got interests to protect.”

“Did Sammy even squeal?”

“He would’ve, if he’d had the chance.”

“And Harriet, she never rang up the D.A., did she?”

“Harriet too, huh?”

“Are you saying—”

“For fuck’s sake, Raul. No. I didn’t know. And you’re taking this awful personal. Do I need to worry about you? Do I need to check the tree?” Then he paused and the moment hung between them. “It’s the goddamn mushrooms, isn’t it? You pulled a card too, son of a bitch. I’m sorry.”

The button man didn’t answer that particular apology. Instead he asked, “Scarfo’s back from New York?”

“He got in this afternoon.”

“Shit.” He struggled to keep the shakes out of his voice. He steadied it, leaning his head on the glass for support and leaving a greasy smudge. He said, “You know, they can’t keep us out forever. They’ll have to let us in eventually. Too many of us to kill. Times’ll change, Moe. They’ll change and leave guys like Ed behind.”

“Tell me something I haven’t known for fifty years.”

The siren wail drew closer. Raul turned his back to hide his face when a car came swinging around the corner, its headlights cutting through the gloom. “I’ve worked for you guys how long now? Twenty years almost, doing my job and nothing else.”

“Nobody joins up for the pension.” Moe sighed. “Do us both a favor, and get out of here. Stay gone. This isn’t your fault, but I can’t help you, not in Chicago. Try New York. I can make some phone calls, Raul. You can start over. You can—”

He didn’t wait to hear the offer.

He slammed the phone back into its receiver and cringed as another car whipped past, a cop car, this time. Its lights slapped streaks of red and blue in every direction until it made the next turn. The button man leaned his shoulder against the hard black phone. His breath was ragged; it fogged thickly against the booth’s scratched-up glass. His shirt cuffs strained against the swelling fungus. Everything too small, everything outgrown.

Maybe he’d find more room in New York.

“The Button Man and the Murder Tree” © 2013 by Cherie Priest

Art © 2013 by John Picacio