This story is also available for download from major ebook retailers.

At a time now past, a cat was born. This was not so long after the first cats came to Japan, so they were rare and mostly lived near the capital city.

This cat was the smallest of her litter of four. Her fur had been dark when she was born, but as she grew it changed to black with speckles of gold and cinnamon and ivory, and a little gold-colored chin. Her eyes were gold, like a fox’s.

She lived in the gardens of a great house in the capital. They filled a city block and the house had been very fine once, but that was many years ago. The owners moved to a new home in a more important part of the city, and left the house to suffer fires and droughts and earthquakes and neglect. Now there was very little left that a person might think of as home. The main house still stood, but the roofs leaked and had fallen in places. Furry green moss covered the walls. Many of the storehouses and other buildings were barely more than piles of wood. Ivy filled the garden, and water weeds choked the three little lakes and the stream.

But it was a perfect home for cats. The stone wall around the garden kept people and dogs away. Inside, cats could find ten thousand things to do—trees and walls to climb, bushes to hide under, corners to sleep in.There was food everywhere. Delicious mice skittered across the ground and crunchy crickets hopped in the grass. The stream was full of slow, fat frogs. Birds lived in the trees, and occasionally a stupid one came within reach.

The little cat shared the grounds with a handful of other female cats. Each adult claimed part of the gardens, where she hunted and bore her kittens alone. The private places all met at the center like petals on a flower, in a courtyard beside the main house. The cats liked to gather here and sleep on sunny days, or to groom or watch the kittens playing. No males lived in the garden, except for boy-kittens who had not gotten old enough to start their prowling; but tomcats visited, and a while later there were new kittens.

The cats shared another thing: their fudoki. The fudoki was the collection of stories about all the cats who had lived in a place. It described what made it a home, and what made the cats a family. Mothers taught their kittens the fudoki. If the mother died too soon, the other cats, the aunts and cousins, would teach the kittens. A cat with no fudoki was a cat with no family, no home, and no roots. The small cat’s fudoki was many cats long, and she knew them all—The Cat From The North, The Cat Born The Year The Star Fell, The Dog-Chasing Cat.

Her favorite was The Cat From The North. She had been her mother’s mother’s mother’s aunt, and her life seemed very exciting. As a kitten she lived beside a great hill to the north. She got lost when a dog chased her and tried to find her way home. She escaped many adventures. Giant oxen nearly stepped on her, and cart-wheels almost crushed her. A pack of wild dogs chased her into a tree and waited an entire day for her to come down. She was insulted by a goat that lived in a park, and stole food from people. She met a boy, but she ran away when he tried to pull her tail.

At last she came to the garden. The cats there called her The Cat From The North, and as such she became part of the little cat’s fudoki.

The ancestors and the aunts were all clever and strong and resourceful. More than anything, the little cat wanted to earn the right for her story and name to be remembered alongside theirs. And when she had kittens, she would be part of the fudoki that they would pass on to their own kittens.

The other cats had started calling her Small Cat. It wasn’t an actual name; but it was the beginning. She knew she would have a story worth telling someday.

The Earthquake

One day, it was beautiful and very hot. It was August, though the very first leaf in the garden had turned bright yellow overnight. A duck bobbed on the lake just out of reach of the cats, but they were too lazy to care, dozing in the courtyard or under the shadow of the trees. A mother cat held down her kitten with one paw as she licked her ears clean, telling her the fudoki as she did so. Small Cat wrestled, not very hard, with a orange striped male almost old enough to leave the garden.

A wind started. The duck on the lake burst upward with a flurry of wings, quacking with panic. Small Cat watched it race across the sky, puzzled. There was nothing to scare the duck, so why was it so frightened?

Suddenly the ground heaved underfoot: an earthquake. Small Cat crouched to keep her balance while the ground shook, as if it were a giant animal waking up and she were just a flea clinging to its hide. Tree branches clashed against one another. Leaves rustled and rained down. Just beyond the garden walls, people shouted, dogs barked, horses whinnied. There was a crashing noise like a pile of pottery falling from a cart (which is exactly what it was). A temple bell rang, tossed about in its frame. And the strangest sound of all: the ground itself groaned as roots and rocks were pulled about.

The older cats had been through earthquakes before, so they crouched wherever they were, waiting for it to end. Small Cat knew of earthquakes through the stories, but she’d never felt one. She hissed and looked for somewhere safe to run, but everything around her rose and fell. It was wrong for the earth to move.

The old house cracked and boomed like river ice breaking up in the spring. Blue pottery tiles slid from the roof to shatter in the dirt. A wood beam in the main house broke in half with a cloud of flying splinters. The roof collapsed in on itself, and crashed into the building with a wave of white dust.

Small Cat staggered and fell. The crash was too much for even the most experienced cats, and they ran in every direction.

Cones and needles rained down on Small Cat from a huge cedar tree. It was shaking, but trees shook all the time in the wind, so maybe it would be safer up there. She bolted up the trunk. She ran through an abandoned birds’ nest tucked on a branch, the babies grown and flown away and the adults nowhere to be found. A terrified squirrel chattered as she passed it, more upset by Small Cat than the earthquake.

Small Cat paused and looked down. The ground had stopped moving. As the dust settled, she saw most of the house and garden. The courtyard was piled with beams and branches, but there was still an open space to gather and tell stories, and new places to hunt or play hide-and-seek. It was still home.

Aunts and cousins emerged from their hiding places, slinking or creeping or just trotting out. They were too dusty to tell who was who, except for The Cat With No Tail, who sniffed and pawed at a fallen door. Other cats hunched in the remains of the courtyard, or paced about the garden, or groomed themselves as much for comfort as to remove the dirt. She didn’t see everyone.

She fell asleep the way kittens do, suddenly and all at once, and wherever they happen to be. She had been so afraid during the earthquake that she fell asleep lying flat on a broad branch with her claws sunk into the bark.

When she woke up with her whiskers twitching, the sun was lower in the sky.

What had awakened her? The air had a new smell, bitter and unpleasant. She wrinkled her nose and sneezed.

She crept along a branch until she saw out past the tree’s needles and over the garden’s stone wall.

The city was on fire.

The Fire

Fires in the capital were even more common than earthquakes. Buildings there were made of wood, with paper screens and bamboo blinds, and straw mats on the floor. And in August the gardens were dry, the weeds so parched that they broke like twigs.

Fires in the capital were even more common than earthquakes. Buildings there were made of wood, with paper screens and bamboo blinds, and straw mats on the floor. And in August the gardens were dry, the weeds so parched that they broke like twigs.

In a home far southeast of Small Cat’s home, a lamp tipped over in the earthquake. No one noticed until the fire leapt to a bamboo blind and then to the wall and from there into the garden. By that time it couldn’t be stopped.

Smoke streamed up across the city: thin white smoke where grass sizzled, thick gray plumes where some great house burned. The smoke concealed most of the fire, though in places the flames were as tall as trees. People fled through the streets wailing or shouting, their animals adding to the din. But beneath those noises, even at this distance the fire roared.

Should she go down? Other cats in the fudoki had survived fires—The Fire-Tailed Cat, The Cat Who Found The Jewel—but the stories didn’t say what she should do. Maybe one of her aunts or cousins could tell her, but where were they?

Smoke drifted into the garden.

She climbed down and meowed loudly. No one answered, but a movement caught her eye. One of her aunts, the Painted Cat, trotted toward a hole in the wall, her ears pinned back and tail low. Small Cat scrambled after her. A gust of smoky wind blew into her face. She squeezed her eyes tight, coughing and gasping. When she could see again, her aunt had gone.

She retreated up the tree and watched houses catch fire. At first smoke poured from their roofs, and then flames roared up and turned each building into a pillar of fire. Each house was closer than the last. The smoke grew so thick that she could only breathe by pressing her nose into her fur and panting.

Her house caught fire just as the sky grew dark. Cinders rained on her garden, and the grass beside the lake hissed as it burned, like angry kittens. The fires in the garden crawled up the walls and slipped inside the doors. Smoke gushed through the broken roof. Something collapsed inside the house with a huge crash and the flames shot up, higher even than the top of Small Cat’s tree.

The air was too hot to breathe. She moved to the opposite side of the tree and dug her claws into the bark as deep as they would go, and huddled down as small as she could get.

Fire doesn’t always burn everything in its path. It can leave an area untouched, surrounded by nothing but smoking ruins. The house burned until it was just blackened beams and ashes. Small Cat’s tree beside it got charred, but the highest branches stayed safe.

Small Cat stayed there all night long, and by dawn, the tall flames in the garden were gone and the smoke didn’t seem so thick. At first she couldn’t get her claws to let go, or her muscles to carry her, but at last she managed to climb down.

Much of the house remained, but it was roofless now, hollowed out and scorched. Other buildings were no more than piles of smoking black wood. With their leaves burned away, the trees looked like skeletons. The pretty bushes were all gone. Even the ground smoked in places, too hot to touch.

There was no sound of any sort: no morning songbirds, no people going about their business on the street. No cats. All she could hear was a small fire still burning in an outbuilding. She rubbed her sticky eyes against her shoulder.

She was very thirsty. She trotted to the stream, hopping from paw to paw on the hot ground. Chalky-white with ashes, the water tasted bitter, but she drank until her stomach was full. Then she was hungry, so she ate a dead bird she found beside the stream, burnt feathers and all.

From the corner of her eye, she caught something stirring inside a storehouse. Maybe it was an aunt who had hidden during the fire, or maybe The Painted Cat had come back to help her. She ran across the hot ground and into the storehouse, but there was no cat. What had she seen? There, in a window, she saw the motion again, but it was just an old bamboo curtain.

She searched everywhere. The only living creature she saw was a soaked rat climbing from the stream. It shook itself and ran beneath a fallen beam, leaving nothing but tiny wet paw prints in the ashes.

She found no cats, or any signs of what had happened to them.

The Burnt Paws

Cats groom themselves when they’re upset, so Small Cat sat down to clean her fur, making a face at the bitter taste of the ashes. For comfort, she recited the stories from the fudoki: The Cat Who Ate Roots, The Three-Legged Cat, The Cat Who Hid Things—every cat all the way down to The Cat Who Swam, her youngest aunt, who had just taken her place in the fudoki.

The fudoki was more than just stories: the cats of the past had claimed the garden, and made it home for those who lived there now. If the cats were gone, was this still home? Was it still her garden, if nothing looked the same and it all smelled like smoke and ashes? Logs and broken roof tiles filled the courtyard. The house was a ruin. There were no frogs, no insects, no fat ducks, no mice. No cats.

Small Cat cleaned her ear with a paw, thinking hard. No, she wasn’t alone. She didn’t know where the other cats had gone, but she saw The Painted Cat just before the fire. If Small Cat could find her, there would be two cats, and that would be better than one. The Painted Cat would know what to do.

A big fallen branch leaned against the wall just where the hole was. She inched carefully across the ground, still hot in places, twisting her face away from the fumes wherever something smoked. There was no way to follow The Painted Cat by pushing through the hole. Small Cat didn’t mind that: she had always liked sitting on top of the wall, watching the outside world. She crawled up the branch.

There were people on the street carrying bundles or boxes or crying babies. Many of them looked lost or frightened. A wagon pulled by a single ox passed, and a cart pushed by a man and two boys which was heaped high with possessions. A stray flock of geese clustered around a tipped cart, eating fallen rice. Even the dogs looked weary.

There was no sign of The Painted Cat. Small Cat climbed higher.

The branch cracked in half. She crashed to the ground and landed on her side on a hot rock. She twisted upright and jumped away from the terrible pain; but when she landed, it was with all four paws on a smoldering beam. She howled and started running. Every time she put a foot down, the agony made her run faster. She ran across the broad street and through the next garden, and the next.

Small Cat stopped running when her exhaustion got stronger than her pain. She made it off the road—barely—before she slumped to the ground, and she was asleep immediately. People and carts and even dogs tramped past, but no one bothered her, a small filthy cat lying in the open, looking dead.

When she woke up, she was surrounded by noise and tumult. Wheels rolled past her head. She jumped up, her claws out. The searing pain in her paws made her almost forget herself again, but she managed to limp to a clump of weeds.

Where was she? Nothing looked or smelled familiar. She didn’t recognize the street or the buildings. She did not know that she had run nearly a mile in her panic, but she knew she would never find her way back.

She had collapsed beside an open market. Even so soon after the earthquake and fire, merchants set up new booths to sell things, rice and squash and tea and pots. Even after a great disaster people are hungry, and broken pots always need to be replaced.

If there was food for people, there would be food for cats. Small Cat limped through the market, staying away from the big feet of the people. She stole a little silver fish from a stall and crept inside a broken basket to eat it. When she was done, she licked her burnt paws clean.

She had lost The Painted Cat, and now she had lost the garden. The stories were all she had left. But the stories were not enough without the garden and the other cats. They were just a list. If everyone and everything was gone, did she even have a home? She could not help the cry of sadness that escaped her.

It was her fudoki now, hers alone. She had to find a way to make it continue.

The Strange Cats

Small Cat was very careful to keep her paws clean as they healed. For the first few days, she only left her basket when she was hungry or thirsty. It was hard to hunt mice, so she ate things she found on the ground: fish, rice, once even an entire goose-wing. Sad as she was, she found interesting things to do as she got stronger. Fish tails were fun to bat at, and she liked to crawl under tables of linen and hemp fabric and tug the threads that hung over the edges.

As she got better, she began to search for her garden. Since she didn’t know where she was going, she wandered, hoping that something would look familiar. Her nose didn’t help, for she couldn’t smell anything except smoke for days. She was slow on her healing paws. She stayed close to trees and walls, because she couldn’t run fast and she had to be careful about dogs.

There was a day when Small Cat limped along an alley so narrow that the roofs on either side met overhead. She had seen a mouse run down the alley and vanish into a gap between two walls. She wasn’t going to catch it by chasing it, but she could always wait in the gap beside its hole until it emerged. Her mouth watered.

Someone hissed. Another cat squeezed out the gap, a striped gray female with a mouse in her mouth. Her mouse! Small Cat couldn’t help but growl and flatten her ears. The stranger hissed, arched her back, and ran away.

Small Cat trailed after the stranger with her heart beating so hard she could barely hear the street noises. She had not seen a single cat since the fire. One cat might mean many cats. Losing the mouse would be a small price to pay for that.

The stranger spun around. “Stop following me!” she said through a mouthful of mouse. Small Cat sat down instantly and looked off into the distance, as if she just happened to be traveling the same direction. The stranger glared and stalked off. Small Cat jumped up and followed. Every few steps the stranger whirled, and Small Cat pretended not to be there; but after a while, the stranger gave up and trotted to a tall bamboo fence, her tail bristling with annoyance. With a final hiss, she squeezed under the fence. Small Cat waited a moment before following.

She was behind a tavern in a small yard filled with barrels. And cats! There were six of them that she could see, and she knew others would be in their private ranges, prowling or sleeping. She meowed with excitement. She could teach them her fudoki and they would become her family. She would have a home again.

She was behind a tavern in a small yard filled with barrels. And cats! There were six of them that she could see, and she knew others would be in their private ranges, prowling or sleeping. She meowed with excitement. She could teach them her fudoki and they would become her family. She would have a home again.

Cats don’t like new things much. The strangers all stared at her, every ear flattened, every tail bushy. “I don’t know why she followed me,” the striped cat said sullenly. “Go away!” The others hissed agreement. “No one wants you.”

Small Cat backed out under the bamboo fence, but she didn’t leave. Every day she came to the tavern yard. At first the strange cats drove her off with scratches and hisses, but she always returned to try again, and each time she got closer before they attacked her. After a while they ignored her, and she came closer still.

One day the strange cats gathered beneath a little roof attached to the back of the tavern. It was raining, so when Small Cat jumped onto a stack of barrels under the roof, no one seemed to think it was worthwhile chasing her away.

The oldest cat, a female with black fur growing thin, was teaching the kittens their fudoki.

The stories were told in the correct way: The Cat Inside The Lute, The Cat Born With One Eye, The Cat Who Bargained With A Flea. But these strangers didn’t know the right cats: The Cat From The North, or The Cat Who Chased Foxes or any of the others. Small Cat jumped down, wanting to share.

The oldest cat looked sidelong at her. “Are you ready to learn our stories?”

Small Cat felt as if she’d been kicked. Her fudoki would never belong here. These strangers had many stories, for different aunts and ancestors, and for a different place. If she stayed, she would no longer be a garden cat, but a cat in the tavern yard’s stories, The Cat After The Fire or The Burnt-Paw Cat. If she had kittens, they would learn about the aunts and ancestors of the tavern-yard cats. There would be no room for her own.

She arched and backed away, tail shivering, teeth bared, and when she was far enough from the terrible stories, she turned and ran.

The Raj? Gate

Small Cat came to the Raj? Gate at sunset. Rain fell on her back, so light that it didn’t soak through but just slid off her fur in drops. She inspected the weeds beside the street as she walked: she had eaten three mice for dinner, but a fourth would make a nice snack.

She looked up and saw a vast dark building looming ahead, a hundred feet wide and taller than the tallest tree she had ever seen, made of wood that had turned black with age. There were actually three gates in Raj? Gate. The smallest one was fifteen feet high and wide enough for ox-carts, and it was the only one still open.

A guard stood by the door, holding a corner of a cape over his head against the rain. “Gate closes at sunset,” he shouted. “No one wants to be wet all night. Hurry it up!” People crowded through. A man carrying geese tied together by their feet narrowly missed a fat woman carrying a bundle of blue fabric and dragging a goat on a rope.

The guard bent down. “What about you, miss?” Small Cat pulled back. Usually no one noticed her, but he was talking to her, smiling and wiggling his fingers. Should she bite him? Run? Smell his hand? She leaned forward, trembling but curious.

Through the gate behind him she saw a wide, busy road half-hidden by the rain. The guard pointed. “That’s the Tokaido,” he said, as if she had asked a question. “The Great North Road. It starts right here, and it goes all the way to the end of Japan.” He shrugged. “Maybe farther. Who knows?”

North! She had never thought about it before this, but The Cat From The North must have come from somewhere, before she became part of Small Cat’s fudoki. And if she came from somewhere, Small Cat could go there. There would be cats, and they would have to accept her—they would have to accept a fudoki that included one of their own.

Unfortunately, The Cat From The North’s story didn’t say where the North was. Small Cat kneaded the ground, uncertain.

The guard straightened and shouted, “Last warning!” Looking down, he added in a softer voice, “That means you, too. Stay or go?”

Suddenly deciding, she dashed through the gate, into the path of an ox-cart. A wheel rolled by her head, close enough to bend her whiskers back. She scrambled out of the way—and tumbled in front of a man on horseback. The horse shied as Small Cat leapt aside. She felt a hoof graze her shoulder. Small Cat streaked into the nearest yard and crouched beneath a wagon, panting.

The gate shut with a great crash. She was outside.

The rain got harder as the sky dimmed. She needed a place to rest and think, out from underfoot until morning. She explored warily, avoiding a team of oxen entering the yard, steaming.

She was in an innyard full of wagons. Light shone from the inn’s paper windows, and the sound of laughter and voices poured out. Too busy. The back of the building was quiet and unlit, with a window cracked open to let in the night air. Perfect. She jumped onto the sill.

A voice screeched inside the room, and a heavy object hurtled past, just missing her head. Small Cat fell from the sill and bolted back to the wagon. Maybe not so perfect.

But where else could she go? She couldn’t stay here because someone would step on her. Everything she might get on top of was wet. And she didn’t much want to hide in the forest behind the inn: it smelled strange and deep and frightening, and night is not the best time for adventures. But there was a promising square shape in a corner of the yard.

It was a small shed with a shingled roof, knee-high to a person and open in front: a roadside shrine to a kami. Kami are the spirits and gods that exist everywhere in Japan, and their shrines can be as large as palaces or as small as a doll’s house. She pushed her head into the shed. Inside was an even smaller building, barely bigger than she was. This was the shrine itself, and its doors were shut tight. Two stone foxes stood on either side of a ledge with little bowls and pots. She smelled cooked rice.

“Are you worshipping the kami?” a voice said behind her. She whirled, backing into the shed and knocking over the rice.

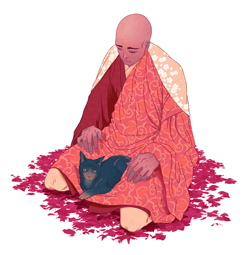

A Buddhist monk stood in the yard. He was very tall and thin and wore a straw cape over his red and yellow robes, and a pointed straw hat on his head. He looked like a pile of wet hay, except for his smiling face.

“Are you catching mice, or just praying to catch some?”

The monk worshipped Buddha, who had been a very wise man who taught people how to live properly. But the monk also respected Shinto, which is the religion of the kami. Shinto and Buddhism did not war between themselves, and many Buddhist temples had Shinto shrines on their grounds. And so the monk was happy to see a cat do something so wise.

Small Cat had no idea of any of this. She watched suspiciously as he put down his basket to place his hands together and murmur for a moment. “There,” he said, “I have told the Buddha about you. I am sure he will help you find what you seek.” And he bowed and took his basket and left her alone, her whiskers twitching in puzzlement.

She fell asleep curled against the shrine in the shed, still thinking about the monk. And in the morning, she headed north along the Tokaido.

The Tokaido

At first the Tokaido looked a lot like the streets within the city. It was packed earth just as the streets had been, fringed with buildings, and overshadowed by trees so close that they dropped needles onto the road. She recognized most of the buildings, but some she had never seen before, houses like barns where people and animals lived under a single high thatched roof.

At first she stayed in the brush beside the road and hid whenever anything approached. And there was always something. People crowded the Tokaido: peasants and carpenters and charcoal-sellers, monks and nurses. There were carts and wagons, honking geese and quacking ducks. She saw a man on horseback, and a very small boy leading a giant black ox by a ring through its nose. Everyone (except the ox) seemed in a hurry to get somewhere else, and then to get back from there, just as fast as they could.

She stayed out of their way until she realized that no one had paid any attention to her since the guard and the monk back at Raj? Gate. Everyone was too busy to bother with her, even if they did notice her. Well, everyone except dogs, anyway, and she knew what to do about dogs: make herself look large and then get out of reach.

The Tokaido followed a broad valley divided into fields and dotted with trees and farmhouses. The mountains beyond that were dark with pine and cedar trees, with bright larches and birch trees among them. As she traveled, the road left the valley and crossed hills and other valleys. There were fewer buildings, and more fields and forests and lakes. The Tokaido grew narrower, and other roads and lanes left it, but she always knew where to go. North.

She did leave the road a few times when curiosity drove her.

In one place, where the road clung to the side of a wooded valley, a rough stone staircase climbed up into the forest. She glimpsed the flicker of a red flag. It was a hot day, maybe the last hot day before autumn and then winter settled in for good. She might not have investigated, except that the stair looked cool and shady.

She padded into a graveled yard surrounded by red flags. There was a large shrine and many smaller shrines and buildings. She walked through the grounds, sniffing statues and checking offering bowls to see if they were empty. Acolytes washed the floor of the biggest shrine. She made a face—too much water for her—and returned to the road.

Another time, she heard a crowd of people approaching, and she hid herself in a bush. It was a row of sedan chairs, which looked exactly like people-sized boxes carried on poles by two strong men each. Other servants tramped along. The chairs smelled of sandalwood perfume.

The chairs and servants turned onto a narrow lane. Small Cat followed them to a Buddhist monastery with many gardens, where monks and other people could worship the Buddha and his servants. The sedan chairs stopped in front of a building, and then nothing happened.

Small Cat prowled around inside, but no one did much in there either, mostly just sat and chanted. There were many monks, but none of them was the monk who had spoken to her beside the tiny shrine. She was coming to realize that there were many monks in the world.

To sleep, she hid in storehouses, boxes, barns, the attics where people kept silkworms in the spring—anyplace that would keep the rain off and some of her warmth in. But sometimes it was hard to find safe places to sleep: one afternoon she was almost caught by a fox, who had found her half-buried inside a loose pile of straw.

And there was one gray windy day when she napped in a barn, in a coil of rope beside the oxen. She awoke when a huge black cat leapt on her and scratched her face.

“Leave or I will kill you,” the black cat snarled. “I am The Cat Who Killed A Hawk!”

Small Cat ran. She knew The Cat From The North could not have been family to so savage a cat. After The Cat Who Killed A Hawk, she saw no more cats.

She got used to her wandering life. At first she did not travel far in any day, but she soon learned that a resourceful cat could hop into the back of a cart just setting off northward, and get many miles along her way without lifting a paw.

There was food everywhere, fat squirrels and absent-minded birds, mice and voles. She loved the tasty crunch of crickets, easy to catch as the weather got colder. She stole food from storehouses and trash heaps, and even learned to eat vegetables. There were lots of things to play with as well. She didn’t have other cats to wrestle, but mice were a constant amusement, as was teasing dogs.

“North” was turning out to be a long way away. Day followed day and still the Tokaido went on. She did not notice how long she had been traveling. There was always another town or village or farmhouse, always something else to eat or look at or play with. The leaves on the trees turned red and orange and yellow, and fell to crackle under Small Cat’s feet. Evenings were colder. Her fur got thicker.

She recited the stories of her fudoki as she walked. Someday, she would get to wherever The Cat From The North came from, and she wanted to have them right.

The Approach

One morning a month into her journey, Small Cat awoke up in the attic of an old farmhouse. When she stopped the night before, it was foggy and cold, as more and more nights were lately. She wanted to sleep near the big charcoal brazier at the house’s center, but an old dog dozed there, and Small Cat worried that he might wake up. It seemed smarter to slip upstairs instead, and sleep where the floor was warm above the brazier.

Small Cat stretched and scrubbed her whiskers with a paw. What sort of day was it? She saw a triangular opening in the thatched roof overhead where smoke could leave. It was easy enough to climb up and peek out.

It would be a beautiful day. The fog was thinning, and the sky glowed pale pink with dawn. The farmhouse was on a plain near a broad river with fields of wheat ready to be harvested, and beyond everything the dim outlines of mountains just beginning to appear as the light grew. She could see that the Tokaido meandered across the plain, narrow because there was not very much traffic here.

The sun rose and daylight poured across the valley. And there, far in the distance, was a mountain bigger than anything Small Cat had ever seen, so big it dwarfed the other mountains. This was Mt. Fuji-san, the great mountain of Japan. It was still more than a hundred miles away, though she didn’t know that.

Small Cat had seen many mountains, but Fuji-san was different: a perfect snow-covered cone with a thin line of smoke that rose straight into the sky. Fuji-san was a volcano, though it had been many years since it had erupted. The ice on its peak never melted, and snow came halfway down its slopes.

Could that be where The Cat From The North had begun? She had come from a big hill, the story said. This was so much more than a hill, but the Tokaido seemed to lead toward Fuji-san. Even if it weren’t The Cat From The North’s home, surely Small Cat would be able to see her hill from a mountain that high.

That day Small Cat didn’t linger over her morning grooming, and she ate a squirrel without playing with it. In no time at all, she trotted down the road. And even when the sky grew heavy the next day and she could no longer see Fuji-san, she kept going.

It was fall now, so there was more rain and whole days of fog. In the mornings puddles had a skin of ice, but her thick fur kept her warm. She was too impatient to do all the traveling on her own paws, so she stole rides on wagons. The miles added up, eight or even ten in a day.

The farmers finished gathering their buckwheat and rice and the root vegetables that would feed them for the winter, and set their pigs loose in the fields to eat the stubble. Small Cat caught the sparrows who joined them; after the first time, she always remembered to pull off the feathers before eating.

But she was careful. The people here had never even heard of cats. She frightened a small boy so much that he fell from a fence, screaming, “Demon! A demon!” Small Cat fled before the parents arrived. Another night, a frightened grandfather threw hot coals at her. A spark caught in her fur, and Small Cat ran into the darkness in panic, remembering the fire that destroyed her home. She slept cold and wet that night, under a pile of logs. After that, Small Cat made sure not to be seen again.

Fuji-san was almost always hidden by something. Even when there was a break in the forests and the mountains, the low, never-ending clouds concealed it. Then there was a long period when she saw no farther than the next turn of the road, everything gray in the pouring rain. She trudged on, cold and miserable. Water dribbled from her whiskers and drooping tail. She couldn’t decide which was worse, walking down the middle of the road so that the trees overhead dropped cold water on her back, or brushing through the weeds beside the road and soaking her belly. She groomed herself whenever she could, but even so she was always muddy.

The longer this went, the more she turned to stories. But these were not the stories of her aunts and ancestors, the stories that taught Small Cat what home was like. She made up her own stories, about The Cat From The North’s home, and how well Small Cat would fit in there, how thrilled everyone would be to meet her.

After many days of this, she was filthy and frustrated. She couldn’t see anything but trees, and the fallen leaves underfoot were an awful-feeling, slippery, sticky brown mass. The Tokaido seemed to go on forever.

Had she lost the mountain?

The sky cleared as she came up a long hill. She quickened her pace: once she got to the top, she might see a village nearby. She was tired of mice and sparrows; cooked fish would taste good.

She came to the top of the hill and sat down, hard. She hadn’t lost the mountain. There was no way she could possibly lose the mountain. Fuji-san seemed to fill the entire sky, so high that she tipped her head to see the top. It was whiter now, for the clouds that rained on the Tokaido had snowed on Fuji-san. Small Cat would see the entire world from a mountain that tall.

Mt. Fuji-san

Fuji-san loomed to the north, closer and bigger each day, each time Small Cat saw it. The Tokaido threaded through the forested hills and came to a river valley that ended on a large plain. She was only a short way across the plain when she had to leave the Tokaido, for the road skirted the mountain, going east instead of north.

The plain was famous for its horses, which were praised even in the capital for their beauty and courage. Small Cat tried to stay far from the galloping hooves of the herds, but the horses were fast and she was not. She woke up one day to find herself less than a foot from a pair of nostrils bigger than her entire body—a red mare snuffling the weeds where she hid. Small Cat leapt in the air, the mare jumped back, and they pelted in opposite directions, tails streaming behind them. Horses and cats are both curious, but there is such a thing as too much adventure.

She traveled as quickly as a small cat can when she is eager to get somewhere. The mountain towered over her, its white slopes leading into the sky. The bigger it got, the more certain she was that she would climb to the top of Fuji-san, she would see The Cat From The North’s home, and everything would be perfect. She wanted this to be true so much that she ignored all the doubts that came to her: What if she couldn’t find them? What if she was already too far north, or not north enough? Or they didn’t want her?

And because she was ignoring so many important things, she started ignoring other important things as well. She stopped being careful where she walked, and she scraped her paws raw on the rough rock. She got careless about her grooming, and her fur grew dirty and matted. She stopped repeating the stories of her fudoki, and instead just told the fantasy-stories of how she wanted everything to be.

The climb went on and on. She trudged through the forests, her nose pointed up the slope. The narrow road she followed turned into a lane and then a path and started zigzagging through the rock outcroppings everywhere. The mountain was always visible now because she was on it.

There were only a few people, just hunters and a small, tired woman in a blue robe lined with feathers who had a bundle on her back. But she saw strange animals everywhere: deer almost small enough to catch, and white goats with long beards that stared down their noses at her. Once, a troop of pink-faced monkeys surprised her by tearing through the trees overhead, hurling jeers.

At last even the path ended, but Small Cat kept climbing through the trees until she saw daylight ahead. Maybe this was the top of Fuji-san. She hurried forward. The trees ended abruptly. She staggered sideways, hit by a frigid wind so strong that it threw her off her feet. There was nothing to stop the wind, for she had come to the tree line, and trees did not grow higher than this.

She tottered to the sheltered side of a rock.

This wasn’t the top. It was nowhere near the top. She was in a rounded basin cut into the mountain, and she could see all the way to the peak itself. The slope above her grew still steeper and craggier; and above that it became a smooth glacier. Wind pulled snow from the peak in white streamers.

She looked the way she had come. The whole world seemed made of mountains. Except for the plain she had come across, mountains and hills stretched as far as she could see.

All the villages she had passed were too far away to see, though wood smoke rose from the trees in places. She looked for the capital, but it was hundreds of miles away, so far away that there was nothing to see, not even the Raj? Gate.

She had never imagined that all those days and all those miles added up to something immense. She could never go back so far, and she could never find anything so small as a single hill, a single family of cats.

A flash of color caught her eye: a man huddled behind another rock just a few feet away. She had been so caught up in the mountain that she hadn’t even noticed him. Under a padded brown coat, he wore the red and yellow robes of a Buddhist monk, with thick straw sandals tied tightly to his feet. His face was red with cold.

How had he gotten up here, and why? He was staring up the mountain as if trying to see a path up, but why was he doing that? He saw her and his mouth made a circle of surprise. He crawled toward her and ducked into the shelter of her rock. They looked up at the mountain. “I didn’t know it would be so far,” he said, as if they were in the middle of a conversation.

She looked at him.

“We can try,” he added. “I think we’ll die, but sometimes pilgrimages are worth it.”

They sat there for a while longer, as the sun grew lower and the wind grew colder. “But we don’t have to,” he said. “We can go back down and see what happens next.”

They started off the mountain together.

The Monk

Small Cat and the monk stayed together for a long time. In many ways they were alike, both journeying without a goal, free to travel as fast or as slow as they liked. Small Cat continued north because she had started on the Tokaido, and she might as well see what lay at the end of it. The monk went north because he could beg for rice and talk about the Buddha anywhere, and he liked adventures.

It was winter now, and a cold, snowy one. It seemed as though the sun barely rose before it set behind the mountains. The rivers they crossed were sluggish, and the lakes covered with ice, smooth as the floorboards in a house. It seemed to snow every few days, sometimes clumps heavy enough to splat when they landed, sometimes tiny flakes so light they tickled her whiskers. Small Cat didn’t like snow: it looked like feathers, but it just turned into water when it landed on her.

Small Cat liked traveling with the monk. When she had trouble wading through the snow, he let her hop onto the big straw basket he carried on his back. When he begged for rice, he shared whatever he got with her. She learned to eat bits of food from his fingers, and stuck her head into his bowl if he set it down. One day she brought him a bird she had caught, as a gift. He didn’t eat the bird, just looked sad and prayed for its fate. After that she killed and ate her meals out of his sight.

The monk told stories as they walked. She lay comfortably on the basket and watched the road unroll slowly under his feet as she listened to stories about the Buddha’s life and his search for wisdom and enlightenment. She didn’t understand what enlightenment was, exactly; but it seemed very important, for the monk said he also was looking for it. Sometimes on nights where they didn’t find anywhere to stay, and had to shelter under the heavy branches of a pine tree, he told stories about himself as well, from when he was a child.

And then the Tokaido ended.

It was a day that even Small Cat could tell was about to finish in a storm, as the first flakes of snow whirled down from low, dark clouds that promised more to come. Small Cat huddled atop the basket on the monk’s back, her face pressed into the space between her front paws. She didn’t look up until the monk said, “There! We can sleep warm tonight.”

There was a village at the bottom of the hill they were descending: the Tokaido led through a double handful of buildings scattered along the shore of a storm-tossed lake, but it ended at the water’s edge. The opposite shore—if there was one—was hidden by snow and the gathering dusk. Now what? She mewed.

“Worried, little one?” the monk said over his shoulder. “You’ll get there! Just be patient.”

One big house rented rooms as if it were an inn. When the monk called out, a small woman with short black hair emerged and bowed many times. “Come in, come in! Get out of the weather.” The monk took off his straw sandals and put down his basket with a sigh of relief. Small Cat leapt down and stretched.

The innkeeper screeched and snatched up a hoe to jab at Small Cat, who leapt behind the basket.

“Wait!” The monk put his hands out. “She’s traveling with me.”

The innkeeper lowered the hoe a bit. “Well, she’s small, at least. What is she, then?”

The monk looked at Small Cat. “I’m not sure. She was on a pilgrimage when I found her, high on Fuji-san.”

“Hmm,” the woman said, but she put down the hoe. “Well, if she’s with you….”

The wind drove through every crack and gap in the house. Everyone gathered around a big brazier set into the floor of the centermost room, surrounded by screens and shutters to keep out the cold. Besides the monk and Small Cat and the members of the household, there were two farmers—a young husband and wife—on their way north.

“Well, you’re here for a while,” the innkeeper said as she poured hot broth for everyone. “The ferry won’t run for a day or two, until the storm’s over.”

Small Cat stretched out so close to the hot coals that her whiskers sizzled, but she was the only one who was warm enough; everyone else huddled inside the screens. They ate rice and barley and dried fish cooked in pots that hung over the brazier.

She hunted for her own meals: the mice had gnawed a secret hole into a barrel of rice flour, so there were a lot of them. Whenever she found something she brought it back to the brazier’s warmth, where she could listen to the people.

There was not much for them to do but talk and sing, so they talked and sang a lot. They shared fairy tales and ghost stories. They told funny stories about themselves or the people they knew. People had their own fudoki, Small Cat realized, though there seemed to be no order to the stories, and she didn’t see yet how they made a place home. They sang love-songs and funny songs about foolish adventurers, and Small Cat realized that songs were stories as well.

At first the servants in the house kicked at Small Cat whenever she was close, but the monk stopped them.

“But she’s a demon!” the young wife said.

“If she is,” the monk said, “she means no harm. She has her own destiny. She deserves to be left in peace to fulfill it.”

“What destiny is that?” the innkeeper asked.

“Do you know your destiny?” the monk asked. She shook her head, and slowly everyone else shook theirs as well. The monk said, “Well, then. Why should she know hers?”

The young husband watched her eat her third mouse in as many hours. “Maybe catching mice is her destiny. Does she always do that? Catch mice?”

“Anything small,” the monk said, “but mice are her favorite.”

“That would be a useful animal for a farmer,” the husband said. “Would you sell her?”

The monk frowned. “No one owns her. It’s her choice where she goes.”

The wife scratched at the floor, trying to coax Small Cat into playing. “Maybe she would come with us! She’s so pretty.” Small Cat batted at her fingers for a while before she curled up beside the brazier again. But the husband looked at Small Cat for a long time.

The Abduction

It was two days before the snowstorm stopped, and another day before the weather cleared enough for them to leave. Small Cat hopped onto the monk’s straw basket and they left the inn, blinking in the daylight after so many days lit by dim lamps and the brazier.

Sparkling new snow hid everything, making it strange and beautiful. Waves rippled the lake, but the frothing white-caps whipped up by the storm had gone. The Tokaido, no more than a broad flat place in the snow, ended at a dock on the lake. A big man wearing a brown padded jacket and leggings made of fur took boxes from a boat tied there; two other men carried them into a covered shelter.

The Tokaido only went south from here, back the way she had come. A smaller road, still buried under the snow, followed the shore line to the east, but she couldn’t see where the lake ended. The road might go on forever and never turn north. Small Cat mewed anxiously.

The monk turned his head a little. “Still eager to travel?” He pointed to the opposite shore. “They told me the road starts again on the other side. The boat’s how we can get there.”

Small Cat growled.

The farmers tramped down to the boat with their packs and four shaggy goats, tugging and bleating and cursing the way goats do. The boatman accepted their fare, counted out in old-fashioned coins, but he offered to take the monk for free. He frowned at Small Cat, and said, “That thing, too, whatever it is.”

The boat was the most horrible thing that had ever happened to Small Cat, worse than the earthquake, worse than the fire. It heaved and rocked, tipping this way and that. She crouched on top of a bundle with her claws sunk deep, drooling with nausea, and meowing with panic. The goats jostled against one another, equally unhappy.

She would run if she could, but there was nowhere to go. They were surrounded by water in every direction, too far from the shore to swim. The monk offered to hold her, but she hissed and tried to scratch him. She kept her eyes fixed to the hills of the north as they grew closer.

The moment the boat bumped against the dock, she streaked ashore and crawled as far into a little roadside shrine as she could get, panting and shaking.

“Sir!” A boy stood by the dock, hopping from foot to foot. He bobbed a bow at the monk. “My mother isn’t well. I saw you coming, and was so happy! Could you please come see her, and pray for her?” The monk bowed in return, and the boy ran down the lane.

The monk knelt beside Small Cat’s hiding place. “Do you want to come with me?” he asked. She stayed where she was, trembling. He looked a little sad. “All right, then. I’ll be back in a bit.”

“Oh sir, please!” the boy shouted from down the lane.

The monk stood. “Be clever and brave, little one. And careful!” And he trotted after the boy.

From her hiding place, Small Cat watched the husband and the boatman wrestle the goats to shore. The wife walked to the roadside shrine and squatted in front of it, peering in.

“I saw you go hide,” she said. “Were you frightened on the boat? I was. I have rice balls with meat. Would you like one?” She bowed to the kami of the shrine and pulled a packet from her bundle. She laid a bit of food in front of the shrine and bowed again. “There. Now some for you.”

Small Cat inched forward. She felt better now, and it did smell nice.

“What did you find?” The farmer crouched behind his wife.

“The little demon,” she said. “See?”

“Lost the monk, did you? Hmm.” The farmer looked up and down the lane, and pulled an empty sack from his bundle. He bowed to the kami, reached in, and grabbed Small Cat by the scruff of her neck.

Nothing like this had ever happened to her! She yowled and scratched, but the farmer kept his grip and managed to stuff her into the sack. He lifted it to his shoulder and started walking.

She swung and bumped for a long time.

The Farmhouse

Small Cat gave up fighting after a while, for she was squeezed too tightly in the sack to do anything but make herself even more uncomfortable; but she meowed until she was hoarse. It was cold in the sack. Light filtered in through the coarse weave, but she could see nothing. She could smell nothing but onions and goats.

Night fell before the jostling ended and she was carried indoors. Someone laid the sack on a flat surface and opened it. Small Cat clawed the farmer as she emerged. She was in a small room with a brazier. With a quick glance she saw a hiding place, and she stuffed herself into the corner where the roof and wall met.

The young husband and wife and two farmhands stood looking up at her, all wide eyes and opened mouths. The husband sucked at the scratch marks on his hand. “She’s not dangerous,” he said reassuringly. “Well, except for this. I think she is a demon for mice, not for us.”

The young husband and wife and two farmhands stood looking up at her, all wide eyes and opened mouths. The husband sucked at the scratch marks on his hand. “She’s not dangerous,” he said reassuringly. “Well, except for this. I think she is a demon for mice, not for us.”

Small Cat stayed in her high place for two days. The wife put scraps of chicken skin and water on top of a huge trunk, but the people mostly ignored her. Though they didn’t know it, this was the perfect way to treat a frightened cat in an unfamiliar place. Small Cat watched the activity of the farmhouse at first with suspicion and then with growing curiosity. At night, after everyone slept, she saw the mice sneak from their holes and her mouth watered.

By the third night, her thirst overcame her nervousness. She slipped down to drink. She heard mice in another room, and quickly caught two. She had just caught her third when she heard the husband rise.

“Demon?” he said softly. He came into the room. She backed into a corner with her mouse in her mouth. “There you are. I’m glad you caught your dinner.” He chuckled. “We have plenty more, just like that. I hope you stay.”

Small Cat did stay, though it was not home. She had never expected to travel with the monk forever, but she missed him anyway: sharing the food in his bowl, sleeping on his basket as they hiked along. She missed his warm hand when he stroked her.

Still, this was a good place to be, with mice and voles to eat and only a small yellow dog to fight her for them. No one threw things or cursed her. The people still thought she was a demon, but she was their demon now, as important a member of the household as the farmhands or the dog. And the farmhouse was large enough that she could get away from them all when she needed.

In any case, she didn’t know how to get back to the road. The path had vanished with the next snowfall, so she had nowhere to go but the wintry fields and the forest.

Though she wouldn’t let the farmer touch her, she liked to follow him and watch as he tended the ox and goats, or kill a goose for dinner. The husband talked to her just as the monk had, as though she understood him. Instead of the Buddha’s life, he told her what he was doing when he repaired harness or set tines in a new rake; or he talked about his brothers, who lived not so very far away.

Small Cat liked the wife better than the husband. She wasn’t the one who had thrown Small Cat into a bag. She gave Small Cat bits of whatever she cooked. Sometimes, when she had a moment, she played with a goose feather or a small knotted rag; but it was a working household, and there were not many moments like that.

But busy as the wife’s hands might be, her mind and her voice were free. She talked about the baby she was hoping to have and her plans for the gardens as soon as the soil softened with springtime.

When she didn’t talk, she sang in a voice as soft and pretty as a dove’s. One of her favorite songs was about Mt. Fuji-san. This puzzled Small Cat. Why would anyone tell stories of a place so far away, instead of one’s home? With a shock, she realized her stories were about a place even more distant.

Small Cat started reciting her fudoki again, putting the stories back in their proper order: The Cat Who Ate Dirt, The Earless Cat, The Cat Under The Pavement. Even if there were no other cats to share it with, she was still here. For the first time, she realized that The Cat From The North might not have come from very far north at all. There hadn’t been any monks or boats or giant mountains in The Cat From The North’s story, just goats and dogs. The more she thought about it, the more it seemed likely that she’d spent all this time looking for something she left behind before she even left the capital.

The monk had told her that courage and persistence would bring her what she wanted, but was this it? The farm was a good place to be: safe, full of food. But the North went on so much farther than The Cat From The North had imagined. If Small Cat could not return to the capital, she might as well find out where North really ended.

A few days later, a man hiked up the snow-covered path. It was one of the husband’s brothers, come with news about their mother. Small Cat waited until everyone was inside, and then trotted briskly down the way he had come.

The Wolves

It was much less pleasant to travel alone, and in the coldest part of winter. The monk would have carried her or kicked the snow away so that she could walk; they would have shared food; he would have found warm places to stay and talked the people who saw her into not hurting her. He would have talked to her, and stroked her ears when she wished.

Without him, the snow came to her shoulders. She had to stay on the road itself, which was slippery with packed ice and had deep slushy ruts in places that froze into slick flat ponds. Small Cat learned how to hop without being noticed onto the huge bundles of hay that oxen sometimes carried on their backs.

She found somewhere to sleep each night by following the smell of smoke. She had to be careful, but even the simplest huts had corners and cubbyholes where a small dark cat could sleep in peace, provided no dogs smelled her and sounded the alarm. But there were fewer leftover scraps of food to find. There was no time or energy to play.

The mice had their own paths under the snow. On still days she could hear them creeping through their tunnels, too deep for her to catch, and she had to wait until she came to shallower places under the trees. At least she could easily find and eat the dormice that hibernated in tight little balls in the snow, and the frozen sparrows that dropped from the bushes on the coldest nights.

One night it was dusk and very cold. She was looking for somewhere to stay, but she hadn’t smelled smoke or heard anything promising.

There was a sudden rush from the snow-heaped bushes beside the road. She tore across the snow and scrambled high into a tree before turning to see what had chased her. It was bigger than the biggest dog she had ever seen, with a thick ruff and flat gold eyes: a wolf. It was a hard winter for wolves, and they were coming down from the mountains and eating whatever they could find.

This wolf glared and then sat on its haunches and tipped its head to one side, looking confused. It gave a puzzled yip. Soon a second wolf appeared from the darkening forest. It was much larger, and she realized that the first one was young.

They looked thin and hungry. The two wolves touched noses for a moment, and the older one called up, “Come down, little one. We wish to find out what sort of animal you are.”

She shivered. It was bitterly cold this high in the tree, but she couldn’t trust them. She looked around for a way to escape, but the tree was isolated.

“We can wait,” the older wolf said, and settled onto its haunches.

She huddled against the tree’s trunk. The wind shook ice crystals from the branches overhead. If the wolves waited long enough she would freeze to death, or her paws would go numb and she would fall. The sun dipped below the mountains and it grew much colder.

The icy air hurt her throat, so she pressed her face against her leg to breathe through her fur. It reminded her of the fire so long ago back in the capital, the fire that had destroyed her garden and her family. She had come so far just to freeze to death or be eaten by wolves?

The first stars were bright in the clear night. The younger wolf was curled up tight in a furry ball, but the old wolf sat, looking up, its eyes shining in the darkness. It said, “Come down and be eaten.”

Her fur rose on her neck, and she dug her claws deep into the branch. She couldn’t feel her paws any more.

Her fur rose on her neck, and she dug her claws deep into the branch. She couldn’t feel her paws any more.

The wolf growled softly, “I have a pack, a family. This one is my son, and he is hungry. Let me feed him. You have no one.”

The wolf was right: she had no one.

It sensed her grief, and said, “I understand. Come down. We will make it quick.”

Small Cat shook her head. She would not give up, even if she did die like this. If they were going to eat her, at least there was no reason to make it easy for them. She clung as hard as she could, trying not to let go.

The Bear Hunter

A dog barked and a second dog joined the first, their deep voices carrying through the still air. Small Cat was shivering so hard that her teeth chattered, and she couldn’t tell how far they were: in the next valley or miles away.

The wolves pricked their ears and stood. The barking stopped for a moment, and then began again, each bark closer. Two dogs hurtled into sight at the bottom of the valley. The wolves turned and vanished into the forest without a sound.

The dogs were still barking as they raced up to the tree. They were a big male and a smaller female, with thick golden fur that covered them from their toes to the tips of their round ears and their high, curling tails. The female ran a few steps after the wolves and returned to sniff the tree. “What’s that smell?”

They peered up at her. She tried to climb higher, and loose bark fell into their surprised faces.

“I better get the man,” the female said and ran off, again barking.

The male sat, just where the big wolf had sat. “What are you, up there?”

Small Cat ignored him. She didn’t feel so cold now, just very drowsy.

She didn’t even notice when she fell from the tree.

Small Cat woke up slowly. She felt warm, curled up on something dark and furry, and for a moment she imagined she was home, dozing with her aunts and cousins in the garden, light filtering through the trees to heat her whiskers.

She heard a heavy sigh, a dog’s sigh, and with a start she realized this wasn’t the garden; she was somewhere indoors and everything smelled of fur. She leapt to her feet.

She stood on a thick pile of bear hides in a small hut, dark except for the tiny flames in a brazier set into the floor. The two dogs from the forest slept in a pile beside it.

“You’re awake, then,” a man said. She hadn’t seen him, for he had wrapped himself in a bear skin. Well, he hadn’t tried to harm her. Wary but reassured, she drank from a bowl on the floor, and cleaned her paws and face. He still watched her.

“What are you? Not a dog or a fox. A tanuki?” Tanuki were little red-and-white striped animals that could climb trees and ate almost anything. He lived a long way from where cats lived, so how would he know better? She mewed. “Out there is no place for a whatever-you-are, at least until spring,” he added. “You’re welcome to stay until then. If the dogs let you.”

The dogs didn’t seem to mind, though she kept out of reach for the first few days. She found plenty to do: an entire village of mice lived in the hut, helping themselves to the hunter’s buckwheat and having babies as fast as they could. Small Cat caught so many at first that she didn’t bother eating them all, and just left them on the floor for the dogs to munch when they came in from outdoors. Within a very few days the man and the dogs accepted her as part of the household, even though the dogs still pestered her to find out what she was.

The man and the dogs were gone a lot. They hunted bears in the forest, dragging them from their caves while they were sluggish from hibernation; the man skinned them and would sell their hides when summer came. If they were gone for a day or two, the hut got cold, for there was no one to keep the charcoal fire burning. But Small Cat didn’t mind. She grew fat on all the mice, and her fur got thick and glossy.

The hut stood in a meadow with trees and mountains on either side. A narrow stream cut through the meadow, too fast to freeze. The only crossing was a single fallen log that shook from the strength of the water beneath it. The forest crowded close to the stream on the other side.

There was plenty to do, trees to climb and birds to catch. Small Cat watched for wolves, but daylight wasn’t their time and she was careful to be inside before dusk. She never saw another human.

Each day the sun got brighter and stayed up longer. It wasn’t spring yet, but Small Cat could smell it. The snow got heavy and wet, and she heard it slide from the trees in the forest with thumps and crashes. The stream swelled with snowmelt.

The two dogs ran off for a few days, and when they came back, the female was pregnant. At first she acted restless and cranky, and Small Cat kept away. But once her belly started to get round with puppies, she calmed down. The hunter started leaving her behind, tied to a rope so she wouldn’t follow. She barked and paced, but she didn’t try to pull free, and after a while she didn’t even bother to do that.

Small Cat was used to the way people told stories, and the bear hunter had his stories as well, about hunts with the dogs, and myths he had learned from the old man who had taught him to hunt so long ago. Everyone had a fudoki, Small Cat knew now. Everyone had their own stories, and the stories of their families and ancestors. There were adventures and love stories, or tricks and jokes and funny things that had happened, or disasters.

Everyone wanted to tell the stories, and to know where they fit in their own fudokis. She was not that different.

The Bear

The last bear hunt of the season began on a morning that felt like the first day of spring, with a little breeze full of the smell of growing things. The snow had a dirty crust and it had melted away in places, to leave mud and the first tiny green shoots pushing through the dead grass of the year before.

Fat with her puppies, the female lay on a straw mat put down over the mud for her. The male paced eagerly, his ears pricked and tail high. The bear hunter sat on the hut’s stone stoop. He was sharpening the head of a long spear. Small Cat watched him from the doorway.

The man said, “Well, you’ve been lucky for us this year. Just one more good hunt, all right?” He looked along the spear’s sharp edge. “The bears are waking up, and we don’t want any angry mothers worried about their cubs. We have enough of our own to worry about!” He patted the female dog, who woke up and heaved herself to her feet.

He stood. “Ready, boy?” The male barked happily. The bear hunter shouldered a small pack and picked up his throwing and stabbing spears. “Stay out of trouble, girls,” he said.

He and the male filed across the log. The female pulled at her rope, but once they vanished into the forest she slumped to the ground again with a heavy sigh. They would not be back until evening, or even the next day.

Small Cat had already eaten a mouse and a vole for her breakfast. Now she prowled the edges of the meadow, more for amusement than because she was hungry, and ended up at a large black rock next to the log across the stream. It was warmed and dried by the sun, and close enough to look down into the creamy, racing water: a perfect place to spend the middle of the day. She settled down comfortably. The sun on her back was almost hot.

A sudden sense of danger made her muscles tense up. She lifted her head. She saw nothing, but the female sensed it too, for she was sitting up, intently staring toward the forest beyond the stream.

The bear hunter burst from the woods, running as fast as he could. He had lost his spear. The male dog wasn’t with him. Right behind him a giant black shape crashed from the forest—a black bear, bigger than he was. Small Cat could hear them splashing across the mud, and the female behind her barking hysterically.

It happened too fast to be afraid. The hunter bolted across the shaking log just as the bear ran onto the far end. The man slipped as he passed Small Cat and he fell to one side. Small Cat had been too surprised to move, but when he slipped she leapt out of the way, sideways—onto the log.

The bear was a heavy black shape hurtling toward her, and she could see the little white triangle of fur on its chest. A paw slammed into the log, so close that she felt fur touch her whiskers. With nowhere else to go, she jumped straight up. For an instant, she stared into the bear’s red-rimmed eyes.

The bear was a heavy black shape hurtling toward her, and she could see the little white triangle of fur on its chest. A paw slammed into the log, so close that she felt fur touch her whiskers. With nowhere else to go, she jumped straight up. For an instant, she stared into the bear’s red-rimmed eyes.

The bear reared up at Small Cat’s leap. It lost its balance, fell into the swollen stream and was carried away, roaring and thrashing. The bear had been swept nearly out of sight before it managed to pull itself from the water—on the opposite bank. Droplets scattered as it shook itself. It swung its head from side to side looking for them, then shambled back into the trees, far downstream. A moment later, the male dog limped across the fallen log to them.

The male whined but sat quiet as the bear hunter cleaned out his foot, where he had stepped on a stick and torn the pad. When the hunter was done, he leaned against the wall, the dogs and Small Cat tucked close.

They had found a bear sooner than expected, he told them: a female with her cub just a few hundred yards into the forest. She saw them and attacked immediately. He used his throwing spears but they didn’t stick, and she broke his stabbing spear with a single blow of her big paw. The male slammed into her from the side, giving him time to run for the hut and the rack of spears on the wall beside the door.

“I knew I wouldn’t make it,” the hunter said. His hand still shook a little as he finally took off his pack. “But at least I wasn’t going to die without trying.”

Small Cat meowed.

“Exactly,” the hunter said. “You don’t give up, ever.”

The North

Small Cat left, not so many days after the bear attacked. She pushed under the door flap, while the hunter and the dogs dozed beside the fire. She stretched all the way from her toes to the tip of her tail, and she stood tall on the step, looking around.

It was just at sunset, the bright sky dimming to the west. To the east she saw the first bit of the full moon. Even at dusk, the forest looked different, the bare branches softened with buds. The air smelled fresh with spring growth.

She paced the clearing, looking for a sign of the way to the road. She hadn’t been conscious when the bear hunter had brought her, and in any case it was a long time ago.

Someone snuffled behind her. The female stood blinking outside the hut. “Where are you?” she asked. “Are you gone already?”

Small Cat walked to her.

“I knew you would go,” the dog said. “This is my home, but you’re like the puppies will be when they’re born. We’re good hunters, so the man will be able to trade our puppies for fabric, or even spear heads.” She sounded proud. “They will go other places and have their own lives. You’re like that, too. But you were very interesting to know, whatever you are.”

Small Cat came close enough to touch noses with her.

“If you’re looking for the road,” the female said, “it’s on the other side, over the stream.” She went back inside, the door-flap dropping behind her.

Small Cat sharpened her claws and trotted across the log, back toward the road.

Traveling got harder at first as spring grew warmer. Helped along by the bright sun and the spring rains, the snow in the mountains melted quickly. The rivers were high and icy-cold with snowmelt. No cat, however tough she was, could hope to wade or swim them, and sometimes there was no bridge. Whenever she couldn’t cross, Small Cat waited a day or two, until the water went down or someone passed.

People seemed to like seeing her, and this surprised her. Maybe it was different here. They couldn’t know about cats, but maybe demons did not frighten them, especially small ones. She wasn’t afraid of the people either, so she sniffed their fingers and ate their offerings, and rode in their wagons whenever she had the chance.

The road wandered down through the mountains and hills, into little towns and past farmhouses. Everything seemed full of new life. The trees were loud with baby birds and squirrels, and the wind rustled through the new leaves. Wild yellow and pink flowers spangled the meadows, and smelled so sweet and strong that she sometimes stepped right over a mouse and didn’t notice until it jumped away. The fields were full of new plants, and the pastures and farmyards were full of babies: goats and sheep, horses, oxen and geese and chickens. Goslings, it turned out, tasted delicious.

Journeying was a pleasure now, but she knew she was almost ready to stop. She could have made a home anywhere, she realized—strange cats or no cats, farmer or hunter, beside a shrine or behind an inn. It wasn’t about the stories or the garden; it was about her.

But she wasn’t quite ready. She had wanted to find The Cat From The North’s home, and when that didn’t happen, she had gone on, curious to find how far the road went. And she didn’t know yet.

Then there was a day when it was beautiful and bright, the first really warm day. She came around a curve in the road and looked down into a broad valley, with a river flowing to a distant bay that glittered in the sun. It was the ocean, and Small Cat knew she had come to the end of her travels. This was North.

Home

There was a village where the river and the ocean met. The path led down through fields green with new shoots, and full of people planting things or digging with hoes. The path became a lane, and others joined it.

Small Cat trotted between the double row of houses and shops. Every window and door and screen was open to let the winter out and the spring in. Bedding and robes fluttered as they aired. Young grass and white flowers glowed in the sun, and the three trees in the center of the village were bright with new leaves.

Everyone seemed to be outside doing something. A group of women sang a love song as they pounded rice in a wood mortar to make flour. A man with no hair wove sturdy sandals of straw to wear in the fields, while he told a story about catching a wolf cub when he had been a child, by falling on it. A girl sitting on the ground beside him listened as she finished a straw cape for her wooden doll, and then ran off, calling for her mother. The geese who had been squabbling over a weed scrambled out of her way.

A man on a ladder tied new clumps of thatch onto a roof where the winter had worn through. Below him, a woman laid a bearskin across a rack. She tied her sleeves back to bare her arms, and hit the skin with a stick. Clouds of dirt puffed out with each blow. In between blows, she shouted instructions up to the man on the roof, and Small Cat recognized that this was a story, too: the story of what the man should do next.

A small Buddhist temple peeked from a grove of trees, with stone dogs guarding a red gate into the grounds. A boy swept the ground in front of a shrine there. Small Cat smelled the dried fish and mushrooms that had been left as offerings: it might be worth her while later to find out more.

Two young dogs wrestled in the dirt by a sheep pen until they noticed her. They jumped to their feet and raced about, barking, “Cat! Cat!” She wasn’t afraid of dogs any more—not happy dogs like these, with their heads high and their ears pricked. She hopped onto a railing where they couldn’t accidentally bowl her over. They milled about, wagging their tails.

A woman stretching fabric started to say something to the dogs. When she saw Small Cat, her mouth made an O of surprise. “A cat!” She whirled and ran toward the temple. “A cat! Look, come see!”

The woman knew what a cat was, and so had the dogs! Ignoring the dogs, ignoring all the people who were suddenly seeing her, Small Cat pelted after the woman.

The woman burst through a circle of children gathered around a seated man. He was dressed in red and yellow, his shaved head shiny in the sun. A monk, but not her monk, she knew right away: this one was rounder, though his face was still open and kind. He stood up as the woman pointed at Small Cat. “Look, look! Another cat!”

The monk and the children all started talking at once. And in the middle of the noise, Small Cat heard a meow.

Another cat?

A little ginger-and-white striped tomcat stood on a stack of boxes nearby, looking down at her. His golden eyes were bright and huge with excitement, and his whiskers vibrated. He jumped down, and ran to her.

“Who are you?” he said. His tail waved. “Where did you come from?”

When she decided to make this her home, she hadn’t thought she might be sharing it. He wasn’t much bigger than she was, or any older, and right now, he was more like a kitten than anything, hopping from paw to paw. She took a step toward him.

“I am so glad to see another cat!” he added. He purred so hard that his breath wheezed in his throat.

“The monk brought me here last year to catch mice, all the way from the capital in a basket! It was very exciting.”

“The monk brought me here last year to catch mice, all the way from the capital in a basket! It was very exciting.”

“There are so many things to do here! I have a really nice secret place to sleep, but I’ll show it to you.” He touched her nose with his own.

“There’s no fudoki,” he said, a little defensively. “There’s just me.”

“And me now,” said the Cat Who Walked a Thousand Miles, and she rubbed her cheek against his. “And I have such a tale to tell!”

Copyright © 2009 Kij Johnson

This is lovely!

FYI: Unlike most tor.com images, you can enlarge these. (Thank you, Torie!) Goni Montes did an amazing job — click on each chapter drawing to see them larger.

Beautiful work, Goñi! But I’m not surprised. The use of negative shapes on some of the spots is especially effective!

Really brilliant illustrations Goñi, love your sense of color.

That was very charming.

(Small typo on page 8: “Could that be where The Cat From The North had begun? She had come from a big hell, the story said.”–should be “hill”

Also there seems to be a link to http://www.tor.com/images/phocagallery/ at the bottom of each page which doesn’t work.)

@@@@@ 5 katenepveu

Fixed, thanks. I’m not seeing the link you’re talking about–can you e-mail me a screenshot?

Misspoke, not a link but a broken image tag, and done.

Charming story, wonderfully illustrated. Well done, all!

I’m curious about one detail. You say the monk’s robes are red and yellow. I can’t help but wonder what school of Buddhism he’d belong to.

Oh, wonderful, most wonderful!