The fantasy world of The Witcher has taken decades to achieve its current level of popularity, propelled to cult status by three successful video games, loyal fans, and skillful promotion. Created by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski, the Witcher series pays homage to a familiar fantasy settings and folklore but also subverts your every expectation, offering something few series manage to deliver: uniqueness. Ardent fans like myself are quick to point out the unmistakable Slavic elements that help to define the universe of The Witcher and play a major role in setting this carefully crafted fantasy world apart from other popular works of genre fiction. The question you may be asking is, “What exactly are those Slavic influences, and how do we recognize them in such a complicated, highly imaginative fantasy setting?”

When we think of a standard, conventional fantasy background, many readers will imagine a version of Medieval Europe with magical elements woven into the plot: dwarfs and elves undermine a dysfunctional feudal system, kings rule, knights fight, peasants plough the fields. Occasionally, a dragon shows up and sets the countryside on fire, causing an economic crisis. Depending on the degree of brutality and gritty realism, the world will either resemble a polished fairy tale or a gloomy hell pit—the kind where a sophisticated elf might become a drug-addicted (or magic-addicted) assassin for hire. Slavic fantasy also tends to rely on this time-tested recipe, borrowing tropes from various European legends, with one notable distinction—most of these fantasy elements are drawn from Eastern European traditions. In the case of The Witcher series, this regional flavor makes all the difference…

A Love Letter to Slavic Folklore

The word “Witcher” (Wiedźmin) itself (or “Hexer,” if we trust the earlier translations), refers to a Slavic sorcerer, one who possesses secret knowledge. A “vedmak” is originally a warlock, who may use his magical powers to heal or harm people, depending on the story (or his mood). In Sapkowski’s series, it is used to describe a monster hunter whose body and mind are altered in order to develop the supernatural abilities required by his demanding profession. The main protagonist, Geralt of Rivia, spends time hunting deadly pests, negotiating with kings and sorcerers, caught between lesser and greater evils, drinking vodka (and not only vodka) and reflecting on the meaning of life and destiny with many of the Slavic-inspired and not-so-Slavic-inspired creatures who cross his path. Most of the mythical entities mentioned in the books appear in numerous folk tales, with each Slavic nation having their own particular version of each. Since the Slavic nations have been separated from each other long enough to develop different languages, these discrepancies in legends and their interpretation should not come as a surprise. Despite all that, most Slavs will recognize a striga/stryga (a female vampiric monster), a rusalka (a female water wraith) or a leshy (a forest spirit) since they all hail from our collective folklore. A monster slayer is another familiar character, although he is not exclusive to the Slavic world.

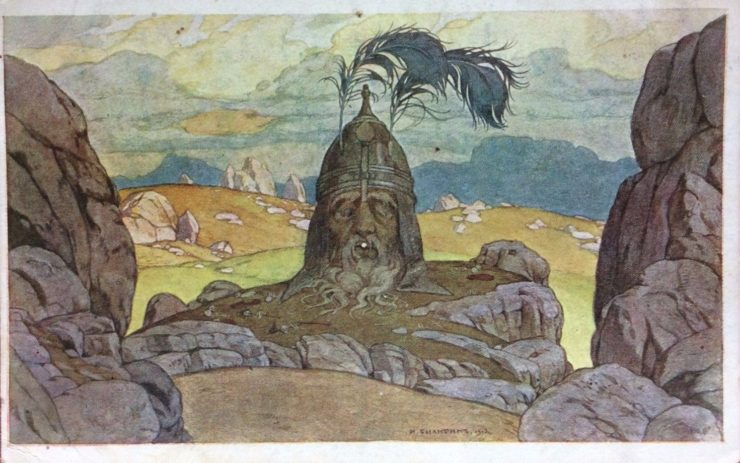

In his depiction of the Slavic spirits, Sapkowski relies heavily on the tradition started by 19th-century Romantic artists and writers. He is neither the first nor far from the last to address these legends, reimagining and drawing inspiration from them. In 1820, the Russian Romantic poet Alexander Pushkin wrote his epic poem Ruslan and Ljudmila, creating what is probably the first Slavic fantasy. In 1901, Antonín Dvořák’s opera Rusalka based on the Slavic fairy tales collected and reworked by the Czech romantic writers, became a European hit. Similarly, the universe of the Witcher series has clearly been created by an author who is familiar with this rich legacy of folklore; he also knows precisely how and when to introduce it. Sapkowski does not base his novels on this tradition entirely, however: three pseudo-Slavic names and a couple mythical spirits do not make a Slavic Fantasy all on their own.

The Slavic Version of Doom and Gloom: Misfits, Outcasts, and Crumbling States

What makes The Witcher unmistakably Slavic, in my opinion, is its overall approach to the genre of fantasy as a whole and its emphasis on marginalization. The Slavic world, with its many facets, has remained largely inaccessible to Western audiences for most of the last century. This isolation has led to stereotypes and confusion that we are still facing. While most Slavs look much like other Europeans, they are not necessarily treated as such by their Western peers. We often blame our challenging languages and the political turmoil of the recent century for our isolation. Also, economic problems and lower standards of living (compared to the Western world) further complicate our position. When Eastern/Central European authors like Sapkowski create their worlds, they often convey that atmosphere of marginalization and political uncertainty through their stories. We recognize it and relate to it.

Buy the Book

Harrow the Ninth

The unnamed continent where the events of the Witcher stories take place is in a state of constant war, always under the threat of epidemics and invasions. Distrust of authorities defines all the characters we encounter: from our protagonist Geralt and the bitter love of his life, Yennefer, to their friends, enemies, and companions. There is not a single character in the series who has faith in institutions or trusts an official to do his job right. And they are never wrong on that count. Most characters hate their governments and lords, and often despise their fellow people—yet, they still fight for them. Geralt himself is an outcast who is constantly mistreated and mistrusted due to his mutations. He drinks heavily and tries to survive and get by, with varying degrees of success. He does his best to stay out of politics but inevitably fails, since his every decision turns out to be political.

In the series, the reader is never provided with a definite, unambiguous antagonist—even the terrifying sorcerer Vilgefortz occasionally exhibits noble intentions and demonstrates reason. His machinations, of course, lead to a dumpster fire. But he is not so much worse than other well-intentioned characters in that regard. Nobody is to blame. Everybody is to blame. That is very much in keeping with what many Eastern Europeans felt in the late eighties and nineties, when The Witcher series was first being written and published. Whether these parallels were intentional or not is another question. The author, to my knowledge, has never given a definite answer.

Some may argue that Eastern Europe does not hold a monopoly on bitter individuals who are disdainful of authority. Also, of course, Slavic-sounding names appear in several fantasy works that have nothing to do with the Slavic World. We may grudgingly agree that Redania is loosely inspired by Medieval Poland with cities like Tretogor and Novigrad, and kings named Vizimir and Radovid. But the Empire of Nilfgaard, the dominant political power in the books, is a mixture of the Soviet Union, the Holy Roman Empire, and even the Netherlands. Similarly, Temeria, Kaedwen and other kingdoms featured in the series are based on so many different elements that we can barely separate history from pure imagination in their case.

The same argument can be applied to the names of the characters and places. Beside the Slavic-sounding Vesemir (Geralt’s fellow witcher and friend), we find the aforementioned mage Vilgefortz and the sorceress Fringilla. I have studied Eastern European history most of my life, and these latter names don’t seem Slavic to me. And yet the larger context surrounding The Witcher, however, does strike me as uniquely Slavic, resonating with me on a particular level. This sense stems from two major sources…

Slavic Literature and Folkore

The first is Sapkowski’s personal background and reliance on specific folkloric and literary traditions in his work. Not every Polish fantasy author inevitably writes about Poland or draws inspiration from Polish literature (the brilliant Lord of the Ice Garden series by Jarosław Grzędowicz, for example, is a non-Slavic blend of dark fantasy and science fiction created by a Polish author). Sapkowski’s case is different, however. The Witcher series, while containing many elements from many disparate cultures, revolves around the crucial events unfolding in the heavily Slavic-inspired Northern Kingdoms.

If you read the books carefully, you will find beautifully integrated references to Russian and Polish classical literature, as well as folklore. For example, the first book begins with Geralt forced to spend a night with a striga in her crypt in order to lift the curse. The striga, of course, rises and tries to snack on Geralt. For those familiar with Nikolai Gogol’s horror story “Viy,” itself inspired by Ukrainian folk tales, the reference is obvious. In “Viy,” a young student reads psalms over a mysteriously dead young daughter of a rich Cossack in a ruined church, trying to set her soul free. The girl, similarly to the striga, rises, attempts to munch on the protagonist and calls other monsters and demons to the party. Unlike Gogol’s protagonist, Geralt survives.

The same story can be seen as a retelling of “Strzyga” by the Polish Romantic poet and folkorist Roman Zmorski. In Zmorski’s tale, the striga is a king’s cursed daughter, a product of an incestuous relationship doomed to feed on human flesh and blood. (There’s an excellent scholarly article comparing Zmorski and Sapkowski, although it is currently only available to read in Polish.) Sapkowski’s version mirrors Zmorski’s setting and borrows Gogol’s plot twists to create something extraordinary and unique, with Geralt as his gritty protagonist. In his subsequent books, Sapkowski uses the same approach to weave other Slavic stories and creatures into his narratives. For example, a race of water-dwelling beings in the Witcher Saga is called the Vodyanoi (or “Vodnik” in the West Slavic tradition). The representation of these mysterious fish-people varies dramatically across the region: depending on the legend, we encounter both grotesque frog-like tricksters and handsome, elven-looking men ruling over marshlands, attended by a court of charming rusalkas. The Slovenian poet France Prešeren promoted the glamorous version of the vodyanoy in his ballad “The Water Man,” while Sapkowski chose to focus on the more mysterious aspects associated with these creatures in The Witcher. His fish-people combine the unconventional appearance of the East Slavic vodyanoy and the secret knowledge and peculiar language of the West Slavic vodniks.

The legacy of Eastern European Romanticism is, of course, not Saprkowski’s only source of inspiration for the series. The first two books contain versions of beautifully remastered fairy tales such as “Beauty and the Beast” and “Snow White,” placed in a darker setting and with wicked twists. These stories, told and retold in so many iterations, have become universal, unlike some of the more specifically Slavic elements woven through Geralt’s adventures. Also, Sapkowski relies heavily on Arthurian myth in the later books. It plays a prominent role in the worldbuilding of The Witcher, particularly in the storyline of Geralt’s adoptive daughter Ciri—a walking wonder-woman hunted or sought out by almost everyone because of her super-special magical genes. Sapkowski goes as far as to set up an encounter between Ciri and Sir Galahad of Arthurian legend, who mistakes the ashen-haired girl for the Lady of the Lake.

Works of purely Slavic fantasy are rare (they exist, mind you!) but that’s not The Witcher: Andrzej Sapkowski is an artist and thus, one should not disregard the impact of his own imagination and ingenuity on his fantasy world. Had Sapkowski written a novel without monsters, prophecies, and curses set in medieval East-Central Europe, it would have been a historical epic, not a tale of sorcerers and magic. In fact, he did write three—they are called the Hussite Trilogy and they are every bit as brilliant as The Witcher series.

The sheer number and variety of references and allusions in the series does not allow me to place The Witcher in the category of a purely Slavic Fantasy, even if the author’s background and his interests may nudge us towards the connections between these books and the rich folkloric tradition of Poland, Russia, and Eastern Europe. However, there’s one thing that definitively sets The Witcher apart from all the Western Fantasy series I’ve read: its fandom.

The Witcher’s Hardcore Slavic Fanbase: We fight for Redania…on the Internet!

The first Witcher stories were published in Poland in 1986. They were translated into Russian in 1991. Other European translations followed soon enough. In a couple of years, The Witcher series had acquired a strong cult following throughout Eastern Europe, especially in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine. By the time the series reached the English-speaking world and becoming a new thing for fantasy fans to discover (starting with the translation of The Last Wish in 2007), my generation has already had our share of debates about the politics of Aen Elle, the Lodge of Sorceresses and, of course the Redanian Army and its organization. The Witcher had become our classic fantasy. Then something unexpected happened. Following the remarkable success of the video games, new people have started to join our club. Since we were fans of The Witcher before it became mainstream (or even known at all in the English-speaking world), many of us have come to view it as a work that is even more deeply Slavic than might be obvious to the rest of the world: we see ourselves in it, and it belongs to us in a way that other fantasy works do not.

Our attitude toward The Witcher resembles the feeling of pride some of us in Eastern Europe experienced following the success of Dmitry Gluchovsky’s Metro series or the successful translations of fantasy novels that we’ve read in the original Russian, Czech, or Polish. We witness these masterpieces’ rising popularity and see the representation of ourselves and our cultures in them. It is the recognition many of us feel has been lacking for too long—the validation of our modern languages and literatures. It is a statement of sorts, especially to those of us who read and write science fiction and fantasy: you don’t need to be an Eastern European political dissident who writes about existential dread (like most of the famous writers from the former Soviet Bloc did) to be read and appreciated, to have your writing matter. It matters to us.

In the end, The Witcher, at its core, remains a Slavic fantasy for us, the old fans who’ve spent decades with these books, and we see it as an integral part of our culture. And with the TV series scheduled to appear later this week, we are looking forward to sharing this world with new fans. It is still too early to talk about the newest adaptation of our beloved books and the possible Slavic motifs the showrunner and writers may or may not introduce into the Netflix version of Sapkowski’s world. While certain changes may elevate the series and add flavor to it, the show will only benefit from the choice to highlight the subtle Slavic elements and clever references to our culture, folklore, and history that make the books so special. After all, they helped to create and fuel our fandom and made The Witcher such a unique experience for us—the distinctive world the author has created, the blending of strange and familiar elements, not quite like anything we’d encountered before. Now we want you to experience that same uniqueness for yourselves.

Teo Bileta is a social historian who focuses on Central and Eastern Europe in her studies. She also plays strategic boardgames and analyzes genre fiction from a historian’s perspective. She is currently based in Budapest.