The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) Directed by Robert Wise. Starring Michael Rennie, Patricia Neal, Hugh Marlowe, Sam Jaffe, and Billy Gray. Screenplay by Edmund H. North, based on the short story “Farewell to the Master” by Harry Bates.

I had never seen this movie before I picked it for this film club. I know it’s a genre classic. I know it’s widely influential and has been referenced in all kinds of sci fi works. I had heard of it, of course, and vaguely knew the premise—alien comes to Earth, Cold War politics—but not much more than that. And I avoided researching it until after I had watched it. I wanted to see it before I delved into what people thought of it.

I’m glad it approached it that way, because: (a) I really enjoyed the movie for itself, because it’s great, and (b) subsequently delving into what people think about The Day the Earth Stood Still is so overwhelming it makes me feel like I’m back in graduate school. For 70+ years people have been writing editorials, reviews, articles, dissertations, and books about the film’s impact and meaning. There are multiple scholarly debates still occurring across both academic journals and fandom spaces: Is the movie anti-war and anti-atomic? Is the main character a Christ-like figure? What is it saying about the doctrine of mutually-assured destruction? Is the position of the visiting alien justifiable from the perspective of ethical philosophy?

All of this is interesting, but there is absolutely no way I can cover everything in this piece, nor do I really want to, not unless somebody is going to give me another PhD for it. So I’m going to focus on a few things that I find most interesting, and I encourage everybody else to share their own thoughts in the comments.

First, a bit about the context, because we are talking about a high-profile, major studio Hollywood movie released in 1951, and there is a hell of a lot of relevant context. A few years earlier, in 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed ten Hollywood producers, directors, and screenwriters to testify about suspected communist activities. They refused to answer any questions, were charged with contempt of Congress, and were subsequently fined and imprisoned. The heads of major studios, along with the Motion Picture Association of America and the Association of Motion Picture Producers, responded by declaring that they would not employ any of those ten men, nor anybody else linked to communist politics or any other vaguely-defined “subversive and disloyal elements.”

The statement they released on the matter, the Waldorf Declaration, is an odd piece of legal wriggling. There was not agreement among the studio heads about what to do, or even if they should do anything. Even at the hysteria-driven height of the so-called Red Scare, it was still, in fact, a violation of the First Amendment to fire somebody for having politics you don’t like, but the pressure to do exactly that was coming from the Congress. The studio heads decided that the financial risk of being sued outweighed the inevitable public backlash if they did nothing. (There are a million articles, books, interviews, and thinkpieces on this matter, but check out this Hollywood Reporter piece for a quick summary and timeline.)

The Waldorf Statement more or less became industry policy for the next few years, and the initial blacklist of ten people ballooned to more than 300, especially after Senator Joseph McCarthy began driving the widespread persecution that would come to bear his name. The impact on Hollywood was significant and very, very high profile. Just a few examples: Charlie Chaplin was denied re-entry to the United States in 1952 and subsequently cut ties with Hollywood; actor Edward G. Robinson, who was an outspoken anti-fascist as well as a civil rights supporter, was called to testify before the HUAC and basically forced to jump through political hoops to avoid being blacklisted; Dashiell Hammett, author of The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man, which became beloved Hollywood movies, refused to cooperate with HUAC and was blacklisted in 1953. The list goes on and on.

Right in the middle of all this came The Day The Earth Stood Still, a major studio film that was conceived, written, and filmed as commentary on the social and political environment in which it was made. Producer Julian Blaustein set out to make a movie about the paranoia and fear that gripped the world in the post-World War II atomic era; he was specifically interested in promoting a strong United Nations and said as much during press for the film. He looked around for a science fiction story that could be used as a basis for such a film and found Harry Bates’ short story “Farewell to the Master,” published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1940. Screenwriter Edmund North took a great many liberties with the original story, as is the way of such things, and the result is the script that director Robert Wise would turn into The Day the Earth Stood Still. Robert Wise would go on to become one of Hollywood’s absolute legends, as he would later direct West Side Story, The Sound of Music, The Haunting, The Andromeda Stain, Star Trek: The Motion Picture and many, many other films. In 1951 he wasn’t a legend yet, but he was well on his way there; he had been the editor on Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) before he began directing his own films.

The Day the Earth Stood Still opens with a montage of people around the world reacting to the appearance of an unidentified craft soaring through Earth’s atmosphere. The craft soon reveals itself to be a sleek flying saucer. Articles about the film frequently claim that set designers Thomas Little and Claude Carpenter designed the spaceship with the help of architect Frank Lloyd Wright (for example: this article shared by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation), but it’s just as frequently claimed that this is an urban legend, so I have no idea if it’s true. If there are any Frank Lloyd Wright biographers hanging around, please let us know.

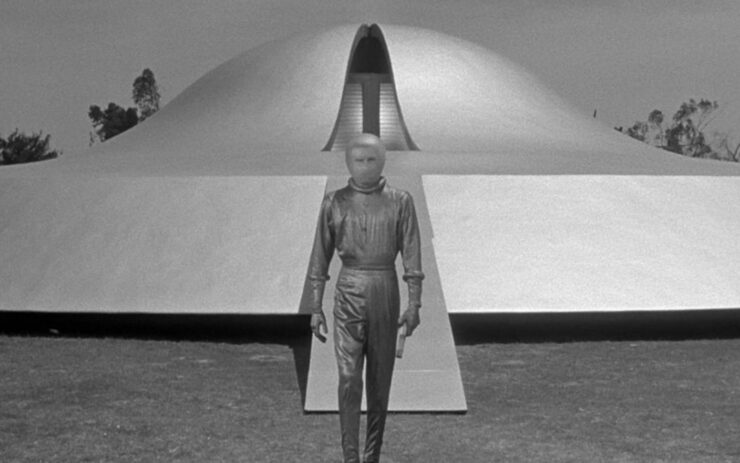

Whoever designed it, the spacecraft is striking and elegant as it settles into a landing spot on Earth: right smack in the middle of the National Mall in Washington D.C.. The ship opens and a humanoid alien emerges to say, “We have come to visit in peace and with goodwill,” and asks to meet with the leaders of Earth. A nervous soldier responds by shooting him, which is one of the most American things that has ever been committed to film. A large robot (played by Lock Martin) from the ship vaporizes all of the soldiers’ weapons, but the injured alien stops him before he can do more damage.

The alien is taken to the hospital, where he introduces himself as Klaatu and asks to speak to representatives of all the world’s governments. Klaatu (Michael Rennie) looks and acts human, which baffles the doctors, but it is necessary for the story the film is telling. Through the 1930s and ’40s, there was significant overlap in American cinema between sci fi films and horror films. There were popular space-based adventures like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, but for the most part American sci fi movies didn’t really begin to distinguish themselves from juvenile serials or monster movies until the ’50s. Another big sci fi release of 1951 was The Thing From Another World. The Thing was more representative of what Hollywood was doing with extraterrestrials at the time: alien visitors to Earth were often monsters and invaders, existing to be fought and feared. There weren’t characters or people. They weren’t us.

Klaatu, a polite, well-spoken alien who can easily pass as human, was a novelty. Wise initially wanted Claude Rains in the role of Klaatu, but he would later say it was a good thing Rains had been unavailable, because Michael Rennie turned out to be such a great alternative. And he was right, because Michael Rennie is fantastic as Klaatu. He’s friendly and warm, but there is a steely solemnity just beneath the surface that reveals the seriousness of his mission. When Klaatu escapes from the hospital, he tries to learn more about Earth and its people by walking around Washington, D.C., staying at a boarding house, spending a day with a child—all very human and ordinary things.

The mundanity of Klaatu’s actions are also key to the story the film is telling. There are very few special effects in The Day the Earth Stood Still; the goal of the production from the start was to give the movie a very realistic, almost documentary-style look. When we see the inside of Klaatu’s ship, it’s very minimalist in design and nothing is explained; when the robot Gort vaporizes human weapons all the audience sees is a blinding flash of white light. The stunning musical score by Bernard Hermann underscores this approach, as it is a compelling mix of recognizably orchestral and notably alien, with two theremins among the array of unusual instruments chosen to create a range of sounds. This was before stereophonic sound was standard in cinema—movies weren’t “presented in stereo!” just yet—and Hermann employed a lot of very clever techniques in both composing and recording to achieve the otherworldly sounds. Hermann is a genuine legend in Hollywood music history; he was wrote the memorable scores of many Alfred Hitchcock movies, several Ray Harryhausen fantasy epics, and many, many other movies you have probably seen. Check out a live performance of the theme of The Day the Earth Stood Still at an international theremin festival in 2018. Seventy years later, and this score is still so eerie, haunting, and beautiful.

The movie has a very clear goal in making these choices: the biology of the alien visitor, the nature of the world he came from, the details of his advanced technology, none of that is what we should be focusing on. What we should be focusing on is ourselves.

Klaatu’s time amongst the people of Earth explores a range of reactions. Presidential representative Mr. Harley (Frank Conroy) is sympathetic to Klaatu’s request to address the world’s leaders but unwilling to explore ways of helping; Mrs. Barley (Frances Bavier) at the boardinghouse thinks there is no extraterrestrial, only a Soviet agent, a conviction she states with confidence while sitting across the breakfast table from the actual alien; Helen Benson (Patricia Neal) thinks about how Earth must appear to an alien visitor who was attacked moments after greeting humans for the first time; her boyfriend Tom (Hugh Marlowe) only cares about alien visitation if it impacts his own life; Helen’s son Bobby (Billy Gray) is curious and excited more than scared. The various military men instantly see a threat to be eliminated, the news reporter is only interested in interviews that will support fear-mongering headlines, but for the most part people keep going about their lives as the tension and paranoia rise. We get glimpses of people around the world that are clearly meant to imply reactions are the same everywhere, including in the Soviet Union.

While tooling around Washington with young Bobby, Klaatu comes to the conclusion that politicians won’t help him deliver the message he needs to deliver, so he turns to scientists. He does this by asking Bobby to identify the smartest man around, a question that really bears no thinking about in a modern context (I do not want to consider what the range of answers would be), but makes a bit more sense in the context of Professor Barnhardt (Sam Jaffe) being an obvious analogue to Albert Einstein, who was hugely popular with the general public at the time. Barnhardt agrees to summon scientists, philosophers, and all manner of thinkers to the city so they can all hear what Klaatu has to say.

What’s most curious about the film’s range of character reactions to alien contact is, perhaps, how very familiar they are to anybody who has watched a movie in the past 70+ years. From E.T.: The Extraterrestrial to Independence Day to The Avengers, the widespread paranoia, the childlike naivete, the military aggression, the scientific curiosity, the selfish disinterest, the histrionic press coverage are all so common they are often compressed into a montage. But here the reactions of the people of Earth aren’t a prelude or epilogue to the story, or an element that must be dispatched with before the action can start. Those reactions are the entire story.

Nothing in The Day the Earth Stood Still is actually about aliens. We learn almost nothing about Klaatu’s home or any other civilizations out there. It’s all about humans, about how we see ourselves, about what we do when we meet somebody a little different, about how we deal with fear and uncertainty.

Because those aspects of the film are so familiar, even comfortable, in the genre of sci fi, I am struck by how strongly I reacted to the ending. At the very end, Klaatu finally has a chance to address thinkers from all over the world. He tells them that because Earth has developed rockets and nuclear weaponry, other civilizations on other planets now view us as a threat. He has come to deliver a warning: change our violent ways, or be destroyed. He explains that his own civilization has achieved peace by outsourcing the enforcement of this moral and ethical dictum to a force of robot police, including his companion Gort, who have the absolute and unretractable mission to destroy any planet that is not sufficiently peaceful.

Now, look, I am an American living in the year 2024. The situation Klaatu describes as peaceful and ideal is, to me, the one of the most horrifying scenarios imaginable. I hate every single thing about it. We can’t even trust cops with handguns to make good choices; I’m sure as fuck not eager to trust a bunch of cops who never have to justify themselves with the power to destroy an entire planet.

But, setting aside my own visceral full-body shudder, I am fascinated by two things about this film’s ending.

The first is that I’m not sure how audiences in 1951 were expected to react to Klaatu’s ultimatum, because reactions were not at all uniform. Within the film itself, we don’t really get a good sense of how the gathered scientists and thinkers react to Klaatu’s message, only that they are taking it seriously. (Any crowd of real scientists would immediately begin arguing, but maybe they wait until Klaatu and Gort have noped out.) The film ends before we get a look at how humanity reacts—which is, of course, the entire point. There are several troubling assumptions behind Klaatu’s ultimatum: that everybody will define terms like threat and violence and freedom in the same way; that a serious enough and clear enough threat will unite the world; that it is possible to create a universal ethical standard that can be enforced without exception; that outsourcing our ethical choices beyond a certain level of significance to external actors is better than making those choices ourselves.

I don’t know that the movie is advocating acceptance of any or all of those assumptions. It is promoting international cooperation as a much better choice than mutually-assured destruction, but there is still skepticism about enforcing peace by means of violence. But, as I have already mentioned, people have been arguing about this for more than 70 years, and will probably be arguing about it for 70 more.

I’ll let the philosophers carry on and move on to the second thing that fascinates me, which is less about what the film itself is saying and more about where it fits into the history of science fiction, because most of the sci fi genre seems to be with me in experiencing that full-body shudder of revulsion. The Day the Earth Stood Still was asking if humankind could or would abandon its violent ways when forced to by an objective, unstoppable external force—and we’ve gotten a lot of answers from other stories over the years. Consider Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), The Terminator (1984), and Robocop (1987), to name just a few films in which humans try to outsource their warfare and policing to machines and it does not, alas, result in peace and harmony for all mankind.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is, like all films, a product of its time and place, but in this way it seems to be a movie that could only have come from that particular time and place. Because the film ends before we learn what humans will decide, there is very much a sense of this being a story that stands on a precipice, one that is looking around at the world in the aftermath of WWII, in an environment of intense fear and paranoia that was actively harming the lives and careers of all kinds of people, and asking, “Now what do we do?”

What do you think about The Day the Earth Stood Still? How do you interpret the promise/threat of Gort’s robot police force and the politics of sci fi during the atomic era? I haven’t watched the 2008 remake with Keanu Reeves, and I’m curious how the story was changed for a different era. Feel free to chime in with your thoughts on that or anything else about this film in comments!

Next week: We’re bringing some different alien visitors down to Earth in The Mysterians (1957), one of the many epic collaborations between director Ishirō Honda and special effects master Eiji Tsuburaya. Watch it on Criterion and FlixFling, and it’s worth checking YouTube, the Internet Archive, and other upload sites. Some of the uploaded versions I’ve found are the English-language dub and some are of very sketchy quality, but poke around a little to find one that works for you.