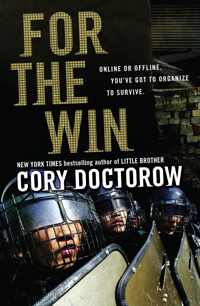

Like much of the best science fiction, Cory Doctorow’s latest novel, For the Win, is set in the future, but its themes are rooted in the present day.

For the Win has the world as its canvas. Its characters start in the industrial slums of China and India, and the adventures take us from there to the posh corporate offices of America.

But the novel isn’t limited to the real world. Much of the action also takes place in cyberspace—the world of online, multiplayer games.

“It’s a book about gold farmers, who are people who do repetitive video game tasks in order to amass virtual wealth, which they then sell through the game market to players who are either too busy or to lazy to do those tasks themselves,” Cory said in an interview, “It’s about what happens when they form a trade union.”

In addition to writing For the Win, Cory co-edits the blog Boing Boing, and is author of other books including Makers and Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town. I interviewed him for my podcast, Copper Robot, in Second Life. You can listen to the whole interview here: MP3. [To download, right click and “save target/link as”.]

For the Win weighs in at 480 pages of adventure, as it follows its teen Chinese, Indian and American heroes through two continents, across the Pacific Ocean, and into a variety of epic fantasy and science fiction gaming worlds. The characters of For the Win fight to get decent working conditions and pay from the bosses who work them in digital sweatshops.

One of the things that impresses me about For the Win is that it starts with a silly premise—a trade union of gold farmers, people who play online games for a living—and quickly delves into some of the most important issues facing the world today: The disparity between rich and poor countries, and exploitation of workers. The novel blossoms.

One of the things that impresses me about For the Win is that it starts with a silly premise—a trade union of gold farmers, people who play online games for a living—and quickly delves into some of the most important issues facing the world today: The disparity between rich and poor countries, and exploitation of workers. The novel blossoms.

That shouldn’t be surprising, according to Doctorow. “Economics is a game. Even economists look at game theory. It’s all about people agreeing to play by a set of rules, and pretending game tokens have intrinsic value. A lot of people have written a lot of ink about whether money is worth something, whether gold is worth something. Whatever value it has comes out of a consensus, and that consensus is not so different from the consensus that virtual gold is worth something or that Monopoly money is worth something.”

Science fiction, says Doctorow, is more about the present than the future. “Science fiction uses changes in the world to illustrate what’s going on in the world today. It uses a kind of warped futuristic mirror to tell a story about the present day. I think even when a writer doesn’t know they’re doing it, they often end up doing it.

“[Isaac] Asimov, for example, clearly was reflecting on things like the New Deal when he started writing about rational technocratic governments that sit down and plan out thousands of years of future history in order to ensure maximum benefit. He really was talking about his present-day technology but coating it in futuristic clothes. He may not have known it, but in hindsight we can see that’s what he was doing.”

One element that I find interesting about Asimov is that his Foundation stories deal with a secret cabal that conspires to manipulate the entirety of human history—and Asimov sees this as Utopian. For Asimov, this secret cabal are the good guys.

Doctorow responded, “Then there’s the idea that they can actually do it. I don’t know which is weirder, the idea that it’s OK to have a star chamber that has humanity’s best interests at heart, that figures out how to manipulate us to do the right thing, or the idea that it would be plausible for them to have done it, that you can actually engineer the future by forcing people into certain pathways that would then produce deterministic outcomes that were stable for hundreds or thousands of years.”

In 2004, Doctorow did a cover story for Wired, interviewing the director of I, Robot, and re-read all the Asimov robot novels in preparation. “What struck me was that he was setting action not just hundreds, but sometimes thousands of years in the future, in which robots were still being made the same way, in which there was some stricture that forced people to build robots with the Three Laws in them, and people weren’t allowed to stray outside that. And I thought that was the most regulated future I’ve ever seen. Implied in Asimov’s work was something like an FCC sitting there punishing anyone who tried to build a robot that didn’t comply with the Three Laws system.”

Doctorow wrote a short story based on the insight, which appears on Scribd: “I, Robot.”

Paul Krugman, the Nobel prize winning economist and New York Times columnist, was influenced to become an economist by Asimov’s psychohistory. He’s a science-fiction fan, and videotaped a conversation with sf novelist Charles Stross at last year’s WorldCon.

But back to For the Win.

Cory’s first attempt at a story based on the premise of unionizing gold farmers was Anda’s Game, published in Salon in 2004. The idea was sparked by a talk he’d heard at a game conference by a man who was paying kids in Latin America to play games and sell their winnings to other, wealthier players. “People really liked the idea,” Cory said. “More and more of this stuff started to happen, and people credited me with predicting it, which was really funny, because of course I didn’t predict it, I observed it. I sometimes say that good science fiction predicts the present, and that’s more or less what happened here.”

I’ll have more from my interview with Cory another day.

Photo of Cory by NK Guy.

Mitch Wagner is a fan, freelance technology journalist and social media strategist. Follow him on Twitter: @MitchWagner.