Walt Disney spent the years after World War II scrambling to recover. Most of his pre-war films had lost money, and World War II had been a particularly hard financial blow for the studio, which survived only by making training films and propaganda shorts featuring Donald Duck. Disney, always ambitious, wanted far more than that: a return, if possible, to the glory days of Pinocchio. Instead, he found himself cobbling together anthologies of cartoon shorts, releasing six between the full length features Bambi and Cinderella.

The last of these was The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. It is, to put it kindly, mixed.

The first part is an adaptation of The Wind in the Willows—that is, if by The Wind in the Willows you mean “Just the parts with Toad in them and not even all of those.” Which for many readers may indeed be an accurate description of The Wind in the Willows, or at least the parts they remember. In all fairness, the framing story for this—someone heading to a library to find the great characters of literature—does focus more on Mr. Toad than anything else, warning us of what’s to come.

Which is, frankly, not much.

Although a The Wind in the Willows animated film had been in production since 1938, work on other films and World War II forced production to be mostly put on hold. By the end of the war, only about a half hour of film had been created, and that half hour, Walt Disney and the animators agreed, was hardly up to the standards of the full length animated films—even the short, colorful and simply animated Dumbo. Disney cancelled plans to animate the rest of the scenes (which, like what remains, would have focused only on the adventures of Mr. Toad, not on the rest of the book), leaving a truncated story that leaves out most of Toad’s adventures.

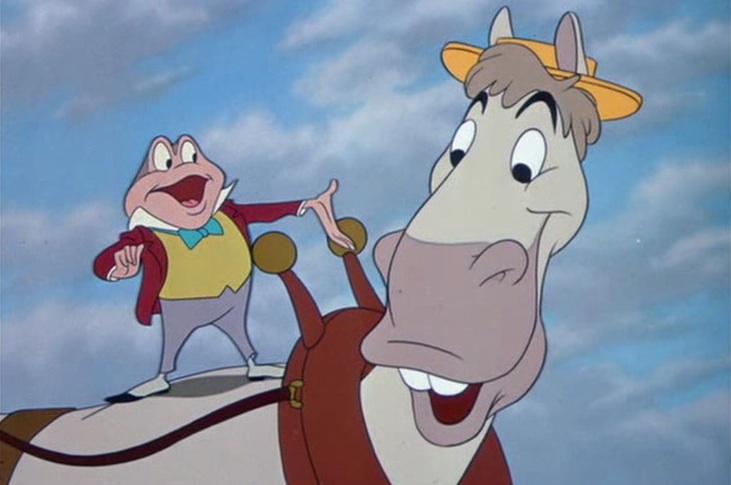

That wasn’t the only change. Disney also added one, mostly unnecessary character—the horse, Cyril Proudbottom (who confusingly enough looks exactly like Ichabod Crane’s horse in the second half of the feature), decided to put Ratty in Sherlock Holmes gear (apparently as a nod to Basil Rathbone, who narrated the film and at that point was arguably best known for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes), somewhat inexplicably made Badger into a less fearsome Scottish nervous wreck, in total contrast to the stern Badger of the books.

But what ultimately keeps this short from working is that it’s so restrained. Toad is a flamboyant, over the top character, something an animated feature should take great joy in—but somehow doesn’t. Part of the problem stems from the decision to pair Toad up with Cyril Proudbottom, who himself is so irresponsible (only slightly less so than Toad) and flamboyant that he takes away Toad’s uniqueness. And then, Cyril doesn’t appear in the climactic battle between Toad and the weasels who have taken over his house, but does get to head off with Toad on the airplane in the end, like THANKS TOAD for remembering the other three friends who helped you out, really, too kind.

And until the end of the short, Toad and Cyril really don’t do anything that outrageous, much less bad, apart from amassing a lot of debts which apparently vanish at the end of the short because…because…I’ve got nothing. Many of those debts do come from the destruction of public property, but we really don’t see any of that onscreen: what we see is Toad and his horse singing and having a good time, and getting accused of theft—as it turns out, completely unfairly. The plot of the short then switches to the need to prove Toad’s innocence, rather than the need for Toad to do something in recompense for his crime.

It’s not that the book Toad was ever particularly remorseful, except when he got caught, and even then—the main character trait of book Toad, after all, is conceit, followed by feeling very very very sorry for himself, and he can always convince himself that he’s in the right, and he’s never really a reformed Toad. But the book makes clear that yes, Toad does owe society something. That partial redemption story (not really all that redemptive) is here replaced by a “Toad is really innocent” story, which is a nice setup for the happy ending with Toad, Cyril and the plane, but also robs the cartoon of Toad’s sheer arrogance and sociopathy, and, I’d argue, a severe misreading of the text. (This is not the first time I’ll be saying that in this reread.)

Having said all that, the final battle in Toad Hall between the weasels and everyone else is kinda fun, I love Mole here (he’s nothing like book Mole at all, but he’s adorable) the short moves quickly, and it has a happy ending. It’s definitely one of the low points of Disney’s early years, but that doesn’t make it completely unwatchable.

The second part, alas, is much less successful, despite the mellow tones of Bing Crosby and a thrilling moment near the end as the Headless Horseman chases Ichabod around and around the forest. The chief problem is that the cartoon short has absolutely no one to root for. Ichabod Crane, the supposed protagonist, has two good qualities: he reads a lot, and dances well. Otherwise, he steals food, leaps from woman to woman, and finally sets his sights on Katrina Van Tassel partly for her looks, and mostly, as the voiceover clarifies, because her father is well to do. Sigh. Beyond this he’s faintly repulsive—I can’t tell if it’s the animation, or the general sense that Ichabod honestly thinks that he’s better than everyone else in town, which is why it’s totally ok for him to use the women of Sleepy Hollow as sources of food.

Unfortunately, his opponent, Brom Bones, is not much better. A sort of precursor to Beauty and the Beast’s Gaston, he’s a bully and a thief. And the girl they are both after? Well, like Ichabod, she’s an excellent dancer, so there’s that. But from what little we see of her, she’s manipulative and eager to see two men fighting over her, and doesn’t particularly care whether or not either of them is hurt in the process.

Also, I found myself gritting my teeth when Bing Crosby told us that Katrina is “as plump as a partridge,” because although she’s amply endowed in certain places, her waist is narrower than her head, proving that Hollywood’s unrealistic standards of thinness are (a) not new, and (b) not confined to live action, but we’ll save some of that discussion for Hercules and Aladdin. Moving on for now.

And there’s the side story where an overweight woman is sitting alone and miserable in the corner because of course nobody wants to dance with her, and of course Brom only asks her in an attempt to cut Ichabod out, leaving Ichabod with the fat woman as Brom happily dances with Katrina, and of course the woman in question is beyond delighted that someone has finally asked her (or even talked to her) and of course this is played for high comedy and if you were wondering, I hated it. Not in the least because I liked her a lot more than I liked Katrina.

In any case, this leaves us with three main characters, all of whom are vaguely to seriously repulsive, two side characters who aren’t in most of the film, and two horses, none of whom we can root for. Well, maybe the horses. This is something that can work well in a serious live action film, but doesn’t work all that well in an animated kids film.

A secondary problem is that, apart from a possible resemblance between the horses ridden by Brom and the Headless Horseman (a resemblance that, in this version, can easily be explained away by poor animation), pretty much all of the nuance of Washington Irving’s original ghost story, which ended on an intriguingly ambiguous note, is lost. Disney was hardly the first or the last to treat Irving’s tale in this way (looking right at you, Fox’s Sleepy Hollow) but it’s one of the few to manage to do so while more or less following the story, and yet manage to lose the impact of the ending. The film has one or two thrilling bits once the Headless Horseman does appear, but otherwise, this can be skipped.

But despite its failures as an overall film, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad had at least three impacts on the Disney legacy. First, in later years, Disney was to eliminate the sorta live action library bit and separate the two shorts, marketing and airing them independently, keeping the films in public view until a later DVD released the full film. Second, it inspired Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, one of the first attractions in Disneyland, and one of the very few of the original attractions still in operation. That in turn inspired the slightly different Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, which has since been replaced by The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh.

And far more critically, the film made just enough money to keep the company alive for a few more months and convince film distributors and theatres that Disney was still alive—letting Walt Disney put the finishing touches on his first major theatrical release in over a decade, Cinderella. Coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.