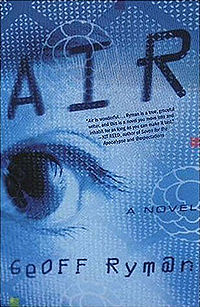

Air (St. Martin’s) is one of the best and most important books so far of the present century. I’ve been a fan of Geoff Ryman’s for years, so I read this as soon as it came out. Even expecting it to be good, I was blown away by it, and it only gets better on re-reading.

Mae lives in a tiny village high in the hills of the imaginary Silk Road country of Karzistan. People in her village are Chinese, Muslim and Eloi. She makes a living by knowing about fashion. It’s the near future, and Air is coming—Air is pretty much internet in your head. Mae has an accident while Air is being tested and winds up getting her ninety-year-old neighbour Mrs Tung’s memories in her head. The book is about the things all literature is about, what it means to be human and how everything changes, but it’s about that against a background of a village that’s the last place in the world to go online. Ryman draws the village in detail, and it all feels real enough to bite—the festivals, hardships, expectations, history, rivalries and hopes.

Air won the Tiptree Award, and even though I really liked it and was glad to see Ryman getting some recognition, I couldn’t figure out why. The Tiptree Award is for books that say something about gender, and I couldn’t see what Air was saying about gender, particularly. On re-reading, I think what it’s saying about gender is that it’s OK to have SF novels about middle aged self-willed Chinese women whose concerns are local and whose adventures are all on a small scale. I think I didn’t notice that because I never had a problem with that being OK, but it is unusual, and it’s one of the things that delighted me about the book.

Mae has a miraculous birth, a child conceived (impossibly!) through a union of menstrual blood and semen in her stomach. This is so biologically impossible that I had to take it as fantastical and move on, and it didn’t look any more plausible to me this time. Metaphorically, it makes sense, realistically it just doesn’t, and as the whole of the rest of the book manages to keep the metaphorical and the realistic in a perfectly complementary balance, this struck me as a problem. The trouble with this sort of thing is that it makes you start questioning everything else.

So “Air” is internet in your head, all right, but how does that work exactly? What’s the power system, and what’s the channel being used? How’s bandwidth? There’s nothing physical involved, how could that possibly work? If I hadn’t pulled away from the book to have a “you what now?” moment over the pregnancy, I doubt I’d ever have started querying the other things. Fortunately, the other things work by cheerful handwavium and the writing and the characters are good enough to carry that… and I wouldn’t even have mentioned it if not for the “Mundane SF Movement” of which Ryman is an exponent. Mundane SF intends to do away with using standard SF furniture and look to the modern world and present day science for inspiration. That’s all very stirring, but when you offer Air as an example, the science ought to have some slight semblance of being realistic. You’ll enjoy the book more if you put aside any such preconceptions and just go with it on occasional excursions into the metaphorical and philosophical.

It’s a fun read, with great characters and sense of place and time and change.