Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 31th installment.

Now this is something special. A European-style graphic novel written by Alan Moore and drawn by Oscar Zarate that looks like something that would be heralded as an astonishingly fresh work of comic book narrative if it debuted at the MoCCA Festival or the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival in 2012. But it’s a book that’s over 20 years old.

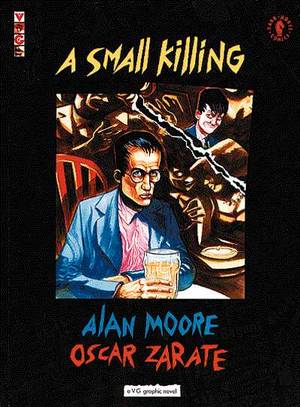

A Small Killing, 96 pages of pain and (self) punishment, trapped in vibrant colors.

A meditation on childhood dreams and adult compromises, drawn and painted like something born from a nightmarish fusion of Brecht Evens and Duncan Fegredo. It is a gorgeous, disturbing graphic novel of the sort that deserves the kind of praise so often heaped upon lesser Moore works like Killing Joke or the aborted Big Numbers.

I can only assume most readers haven’t seen A Small Killing, or haven’t looked at it recently, because it deserves to be part of the critical conversation about Moore, and should be on the shortlist of significant graphic novels throughout history.

I know I was guilty of overlooking it in the 1990s as well. It seemed like a weird, sideline work from Moore, lacking the expansive ambition of what he had done before, or seemed to promise for the future. But, looking back on the book from the perspective of today, I’m astonished by how sharp the package is. A Small Killing is no minor work by a major creator. It’s a key text in the Moore pantheon, providing insight into his own personal struggles as a creator – and as an adult – while presenting a condemnation of the culture around him.

Not only is it better than I remembered it, but it’s a book overdue for a massive critical reappraisal. Let’s start that tidal wave of reconsideration today. Join me, won’t you?

A Small Killing (VG Graphics, 1991)

The inspiration for the story apparently came from Zarate, who told Moore he had an idea about “an adult who was pursued by a child.” The 2003 Avatar Press reprinting of the graphic novel features interview excerpts where Zarate and Moore discuss the origins of the project, and that one image of a child relentlessly chasing a man, was the genesis of everything that followed.

Moore, with more than generous input from Zarate, peeled back that image, and, in his own mind, saw an adult chased by his former self. A child disappointed by what the adult version of him had become. And he used that core idea to construct a story that was unlike anything he had written before.

A Small Killing is less of a constructed edifice and more of a dream-like narrative. Though a Nabokov/Lolita motif runs through the graphic novel, there are also allusions to the films of Nicolas Roeg, and the story feels more in tune with the latter’s work than the former. Or, more accurately, the story seems it was crafted by someone influenced by the soul of Roeg and the mind of Nabokov. The wordplay an image patterns recall the Nabokov author, but the elliptical structure and bold, haunting iconography recall Don’t Look Now.

Moore and Zarate balance both of those quite divergent influences, but offer something fresh in the synthesis. The Nabokov/Roeg substructure works like an echo, and Moore and Zarate seem in control of their subject the entire way through.

The story revolves around Timothy Hole (pronounced “Holly”) and his disturbing run-ins with a precocious, almost demonic child who increasingly derails his life. Hole becomes obsessed with this child, who we identify almost immediately as some kind of spectral figure, perhaps from his own past, and it doesn’t take long to realize that Hole is haunted by his own younger self. It’s a metaphorical haunting made flesh. Hole has compromised everything he valued as a child – everything he wanted to be has been given away in favor of short-term gains and immediate pleasures – and his younger self continually pops up at strange moments to silently remind Hole what he’s lost.

But from Hole’s point of view, this odd young boy keeps following him, or appearing in the roadway suddenly, causing him to crash his car. For Hole it’s a different kind of horror story, a monster movie where he can’t find the monster that’s chasing him, and doesn’t know what this juvenile creature wants. For the reader, it’s a horror story about a man who doesn’t realize what he’s become, and must face down the shadows of his past before he can move to a better future.

What could be too-clever, bludgeoning symbolism is deftly presented by Moore and Zarate. The core conflict – flawed man versus the idealism of his youth, given literal form—is like something out of a Jose Saramago novel. But because the creative team is working in a visual medium rather than prose, instead of exploring the metaphysical questions raised by the inner conflict, they turn the conflict into a dramatic chase.

Except, the chase is interwoven, non-chronologically, with scenes from Timothy Hole’s life. The chase threads throughout, and leads to the climax of the book, but the information doled out in the cut scenes add significant layers of meaning to the story. It’s a sophisticated structure, ultimately, but it never feels like the clockwork machinery of Moore’s best-known work. Instead, it feels more organic, experimental, profound.

What’s constantly astounding about A Small Killing is that, even with its simple central conflict and its overt use of symbolism and repetition, it still seems larger than its page count. It’s like you can’t quite grasp the entirety of the story, because of its elusive edges and its refusal to justify all of its moments. Some scenes explain, but others just present experiences, uncompromisingly, and leave the reader to render a sense of meaning onto the impressions. It’s the kind of thing that great literature does, that great films do, but comics have historically struggled to pull off.

Taken as a whole, it’s an extraordinarily impressive piece of work, but even on the page level, there are treats to offer the reader.

Page 55 for example (and the pages in the edition I’m looking at aren’t numbered, so the numbering may not be exact here), with the quiet domestic furniture scene in the opening two panels and the narration: “I can think about Maggie. Our marriage…it was just something left over from when we were kids. It wasn’t real.” But then a giant eye peers in, thorough what looks like a blank canvas behind the green love seat.

The whole thing is a doll house, with Timothy and Maggie talking about art and socializing and reputation. Their fragile marriage symbolized with everything in the scene. (We already know that they have broken apart, because we’ve seen pieces of Timothy’s affair.)

Timothy’s eye peers out at us, in that third panel, but in each following panel on the page, he looks away, bundled in his own obsessions, while Maggie looks at him. He’s withdrawn, and she is trying to engage.

Or page 41, with a top tier and bottom tier in the narrative present, with Timothy pursuing the glowing embodiment of his childhood, the middle tier – broken up into three panels – presents a troubling conversation in which his mistress talks about an abortion but clearly hints that she wants to keep the child. No eye contact at all in this scene, and their conversation directly contradicts what Timothy has said about her in another scene. He blamed her for being competitive and manipulative, but here she’s shown as vulnerable, looking for some support from the man who would be the father of her child.

And these are just two random pages, selected because I flipped through them as I sit here reflecting on the comic. A Small Killing is packed with meaning. Each page has a sense of mystery to it, but also carefully-crafted storytelling decisions.

In the end, Timothy confronts his doppelganger, his younger self, in a scene of sunken memories and hidden secrets. The child is vicious, filled with murderous rage towards the man who has given up art for commerce, who has betrayed his friends for profit, who has destroyed relationships for carnal pleasure. Man versus boy and only one of them climbs up out of the pit and faces the sunshine of the next day. It’s a definitive ending, but not one that provides an easy answer. The interpretation is yours to make.

The most highly-regarded “literary” graphic novels of all time – name whatever famous Top 5 pops into your head – are almost sure to be memoirs, presented in an overly-literal, likely chronological order. Maus, Persepolis, or Fun Home. Something like that. Or, on the other end of things, formal masterpieces that are difficult to connect with emotionally. Jimmy Corrigan? Ice Haven? Asterios Polyp? A Small Killing is that rare beast of a fiction graphic novel that steals from what prose, poetry, and film can do, but tells the story as only comic books can. It’s as good as any of the other books listed above, and yet I’ve never seen it mentioned in the same sentence as any of the others.

What a pleasure it was to reread this book by Alan Moore and Oscar Zarate. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

NEXT TIME: Image Comics proudly presents…Spawn, by Alan Moore

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.