Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the very first installment.

Though I’ll basically travel chronologically through the Alan Moore catalogue over the next year, I decided to start with Miracleman from Eclipse Comics because (a) it reprints the opening installments of Moore’s first long-form narrative, (b) I don’t have copies of the original Warrior magazine issues handy, even though I have read them, and (c) the Marvelman/Miracleman stories kicked off the Modern Age of superhero comics, so it’s a fitting place to begin our look at this most Modern of superhero comic book writers.

Originally published in England in early 1982, Alan Moore and Garry Leach’s “Marvelman” serial was just one of several regular entries in the black-and-white Warrior anthology edited by Dez Skinn. With the “Marvelman” series and Moore’s own “V for Vendetta” alongside work from Moore’s U.K. comics compadres like Steve Moore, Steve Dillon, and John Ridgway on chapters of “Laser Eraser and Pressbutton” and “The Legend of Prester John,” Warrior remains one of the most impressive anthology series in the history of comics, even though it lasted merely 26 issues and received limited distribution outside of the U.K.

Before writing the script for the first eight-page episode of “Marvelman,” Moore had written a few brief sci-fi “Future Shocks” for 2000 AD and a handful of Doctor Who and Star Wars shorts for various Marvel U.K. publications, and he’d worked for years as an alternative cartoonist in music magazines under the name “Curt Vile,” but nothing in Moore’s early work hinted at how radically he would change the superhero genre starting in Warrior #1.

Ultimately, due to tale payments and internal politics, Alan Moore and (then-“Marvelman” artist) Alan Davis walked away from the book with their series not only unfinished, but with a dangling cliffhanger.

Eclipse Comics began republishing the “Marvelman” serials a year later, renaming the character and the comic as “Miracleman” to avoid potential lawsuits from Marvel Comics. The stark black-and-white art by Garry Leach and Alan Davis was colored for the first time, and by Miracleman #6, new Alan Moore-penned stories began appearing, picking up where the Warrior cliffhanger had left off. And, as Alan Moore reminds us in the text page of issue #2, the protagonist “isn’t really called Miracleman at all.” He always was, and always will be Marvelman, even if the lettering on the inside and outside of the Eclipse Comics version spells it M-I-R-A-C-L-E-M-A-N.

So even though these comics are called Miracleman, I’m going to refer to the character as Marvelman throughout. Because that’s his name.

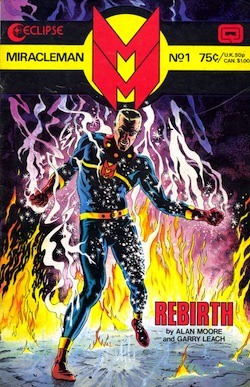

Miracleman #1 (Eclipse Comics, 1985)

The Eclipse reprints begin by flashing back farther than the Alan Moore stories, to a Mick Anglo Marvelman story from twenty-five or thirty years earlier, with some revised dialogue by Alan Moore. Quick history lesson: Marvelman was created as a Captain Marvel (of Shazam! Fame) knock-off for the U.K. market. Just like Captain Marvel, Marvelman had his own “Family” of equivalently-powered companions, like Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman. When the “Marvelman” series began in “Warrior,” it didn’t begin with any reprints of past Marvelman stories, it just jumped right into the new Alan Moore material, presuming a general familiarity with the character from the beginning. Eclipse Comics clearly wanted to provide context to show what exactly Alan Moore and his artists would be deconstructing in the pages of Miracleman. End of history lesson.

The opening “retro” chapter works well to provide a sense of the innocent and yet weirdly violent earlier days of the Marvelman Family as they fight “Kommandant Garrer of the Science Gestapo” from the far future of 1981. We meet Marvelman, Young Marvelman, and Kid Marvelman and get a sense of their powers and the patriarchal relationship the hero has with the two younger boys. That’s all we really need.

It is a strange choice to jump right into the older material without a framing sequence to begin the issue. I doubt any current publisher would take this strategy, since it trusts that the reader will stick around through the goofy weirdness of late-Golden Age storytelling (even with revised dialogue) to get to the revisionist, Modernist approach later in the issue.

“…A Dream of Flying” is where the story really begins. Chapter 2 here, but Chapter 1 in the original Warrior version. It’s a strong start. Even now, after the techniques in this chapter have been adapted, stolen, reimagined, redeployed, and recontextualized a billion times by other superhero comics writers in the years since, the first Alan Moore “Marvelman” chapter – and this is even more true for the chapters that immediately follow – still has the power to impress.

It suffers from the coloring, which is too saturated, and bleeds too much into the negative spaces that worked so well in Garry Leach’s black-and-white originals. If this series ever does get reprinted, which may happen from Marvel (who now sort of owns the rights, maybe), then I hope we get a black-and-white version or a more subtle recoloring job from someone who won’t try to overpower the art with flesh tones and yellows and purples and blues.

Plot-wise, “…A Dream of Flying” introduces us to Michael Moran, a middle-aged husband with bad dreams. A journalist covering a protest at a nuclear power plant, Moran soon remembers the magic word that turns him into a superhero. With the word “Kimota!” Marvelman appears, dispatches some terrorists, and flies up toward the moon shouting “I’m back!” The quasi-realism of the telling of the story helps frame it in a far less ridiculous way than a summary makes it sound, and throughout, we get narrative captions that are filled with signature Alan Moore poetry:

And then there is only the inferno about him as he falls. Inexplicably, a word forms on scorched lips…

A dream-word with alien syllables…

The last thing he hears is the sound of thunder…”

It’s a style that has been copied and parodied over the years, but when this story first appeared in 1981, no one had written comic book captions quite that way, and in the thirty years since, very few have done it nearly as well.

Chapters 3 and 4 of Miracleman #1 provide even more examples of Alan Moore’s poetic captions and his revisionist approach to superheroes. When Moran returns to his wife, in the form of Marvelman, his wife deflates his entire persona. She not only questions his newfound appearance, though not in the way you might expect in a more cliché-ridden comic (where she might gasp, “Mike, how could you hide this secret from me?”), but also deconstructs the entire superhero genre by outwardly protesting about how “bloody stupid” Marvelman’s whole backstory is. She doesn’t even remember a hero by the name of Marvelman from the 1950s. And if her husband were a long-dormant hero that had saved the world countless times, surely she would have at least heard of him and his costumed companions.

But it’s as if they never existed, even though we see the costumed, glowing Marvelman on the page in front of us.

And the first Eclipse issue ends with the ominous appearance of Johnny Bates, the former Kid Marvelman from the opening flashback and from the memories of Mike Moran. Bates has ascended to become a captain of industry while Moran has been wallowing in strange dreams and middle-aged paunch. And it seems as if the former Kid Marvelman has plenty of secrets himself.

The realism of the storytelling and setting, the lack of flamboyant “superheroic gestures,” the poetic captions, the characters actually talking to one another instead of making declarations, the strong female character who questions everything about the genre in which she exists, and the vicious underpinning of the whole tale – these were not techniques that had been seen in superhero comics before “Marvelman.” Not seen this comprehensively, this effectively.

Miracleman #2 (Eclipse Comics, 1985)

Artist Garry Leach fades out in this issue as Alan Davis comes in first as penciler (for Leach to ink) then as full artist himself.

In this issue, we get the battle between Marvelman and his former protégée, lasting for the first two chapters, in a brutal slugfest that shows the consequences of violence, not just on the two participants, but on the bystanders as well. Moore subverts the normal hero-saves-the-falling-baby motif, as Marvelman flies into to rescue a jeopardized child but causes some broken bones in the process, and the worried mother is appropriately angry about the whole scene.

Stylistically, the realism of the drawings are undermined by the occasional sound-effect, and the discord between the two techniques reminds us that this was a new approach to superhero comics, and they hadn’t quite figured out that the balloon-like sound effects look inappropriately absurd in this context.

The story is still a humdinger of an action tale, though, even with its clumsy parts and its implicit self-deconstruction. It gives the reader the requisite fight scene, satisfyingly so, while providing a subtext pointing at how these kinds of fights would really be nothing like the way they’ve been portrayed by superhero comics in the past. Violence is horrible. But not so horrible that it isn’t entertaining.

By the middle of this issue, by the way, Johnny Bates has reverted to the form of a child, and his powers seem stripped forever, but in the very next chapter Moore clues us in that there will be much more story to be told about young Bates, as docile as he seems to be.

More deconstruction follows as Liz Moran and her husband head outside of town to explore Marvelman’s powers, and she points out the physical impossibility of what he seems capable of doing. She applies logic to superheroes, always a tricky approach, and determines that his power must be telekinetic, not physical. It’s the same explanation John Byrne would later use, unnecessarily, to explain Superman’s impossible strength and flying abilities. Superman doesn’t need any such explanation, though, since he’s a comic book character. A symbol. Marvelman, as written by Alan Moore intersects with reality, and the explanation provides a “realistic” context for this new approach to superhero storytelling. One that Superman wouldn’t benefit from, because Superman can’t ever really change. Under Moore, Marvelman can. He is affected by, and he directly affects, the world around him. With great consequences, as we’ll see.

There’s a great, and very human, scene to close out this issue, as Moran, in an elevator, is asked to hold a baby while a young mother fishes through her purse. It’s a trap. The baby is there to prevent Moran from saying his magic word and turning into Marvelman, because the flash of energy would incinerate the infant and Moran knows it. He’s shot twice in the gut by another passenger in the elevator: Evelyn Cream, the man with the shiny blue smile. He sees the jovial, messy face of the baby as he falls into unconsciousness and wonders, “why sapphire teeth?”

The point is that Moore, for all his reputation as an iconoclast and a comics-storytelling pioneer, also knows how to write really compelling scenes which punch the reader right in the gut. He’s just a masterful writer, and even this very early work shows it.

Miracleman #3 (Eclipse Comics, 1985)

The opening chapter of issue #3 plays around with narrative time, as we begin with a flash-forward on page 1 (without any caption saying “two hours from now” or anything like that) and a silhouette of three men talking about what will inevitably happen, recurring on the bottom third of every page, as they narrate what will go on as Marvelman finds his way to the secret installation that houses the secrets of his past.

Sir Dennis Archer, involved with Marvelman’s true past in the story (which we’ll find out more about soon enough), and one of the recurring figures in silhouette, refers to Marvelman as a “creature,” and discusses how they will stop him (or it) from getting to “the bunker.”

Evelyn Cream hasn’t actually killed Mike Moran, just shot him with tranquilizers, as the third timeline reveals.

So we end up with a chronology in this opening chapter that flashes from the near future to the present to the past and back and forth, in the span of seven pages. And Marvelman does make it to the bunker, where he meets his modern counterpart – a new, flawed superbeing created from the vestiges of the Zarathustra Project that spawned Marvelman, even if we don’t really know anything about that project yet.

This new guy looks even more ridiculous than Marvelman. Sporting a bowler hat, and a tight leather three-piece suit with a flower in his lapel and a domino mask (oh, and an umbrella), he’s Big Ben. And he’s in Marvelman’s way.

The rest of the issue shows the fallout from standing in Marvelman’s way and trying to stop him from finding out the truth of his past. Big Ben doesn’t fare well, and in the closing scene of the issue, his battered form is taken away in a straightjacket, and his deluded psyche imagines that his superhero pals Jack Ketch and Owlwoman are taking him home. It’s actually a couple of scientists, carting him off in the back of a delivery truck.

But before that happens, Marvelman learns the true nature of his secret origin. Yes, he did have adventures with Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman. In his mind. In a dream world constructed by Dr. Emil Gargunza, using alien technology that had crash-landed on Earth. Moran was strapped to machines the whole time, imagining his superhero adventures. Thanks to alien technology and something called infra-space, he did share his consciousness with a superior form – with a superhuman body that he would one day manifest as the “real” Marvelman in the “real” world. But he was never meant to escape from the facility. He, and the two boys, were human lab rats.

Watching the video replay he finds in the bunker, Marvelman sees Emil Gargunza’s recorded visage, and hears the words that deconstruct his life: “By employing the technology gleaned from the visitor and his craft, we have completely programmed the minds of these near-divine creatures…providing them in the process with an utterly manufactured identity which is ours to manipulate at will. To whit: the identity of a children’s comic-book character.”

Alan Moore provides a scene with devastating emotional impact and reduces the entire fictional history of the character to a deluded daydream while still making those older stories resonate because they were the only time the character could actually feel free.

So when Marvelman destroys the bunker, he’s lashing out at the violation he’s experienced, the invalidation of his entire life, but he’s left with the knowledge that, yes, this happened, and now he must live knowing the truth. It sets up the confrontation between Marvelman and Gargunza, but with a far greater level of conflict than just, “oh, the bad guy wants to rob a bank, or take over the world.” No, in Alan Moore’s hands, the conflict is personal, tragic, and inescapable. It’s no longer a superhero story. It never was. Not really. It’s a story about identity and revenge. Tearing the walls of superhero fiction down around itself, as it provides, paradoxically, one of the most powerful superhero stories ever told.

Wow, this Alan Moore guy is good.

NEXT TIME: Marvelman/Miracleman, Part 2

Tim Callahan writes about comics. Follow him on Twitter: TimCallahan