Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve monthsmore than a year to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics(and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 59th installment.

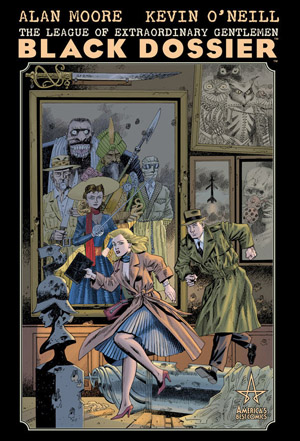

Originally planned as a sourcebook like 1982’s Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, or 1984’s Who’s Who in the DC Universe, or 1994’s The Wildstorm Swimsuit Special (okay, maybe not that last one), full of text-heavy informational pages about the world of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the project that was finally released as the Black Dossier was something far more ambitious: an assembly of multiple styles in multiple parodic modes covering the entire history of the League in all its incarnations and providing far more in the way of discursive storytelling than anything in the way of traditional exposition about who the League is and how it came to be.

I recall the project being the most divisive release from the Alan Moore/Kevin O’Neill team, with the widespread opinion that the project was alternately pretentious and self-indulgent balanced out by a powerful minority of voices thrilled by the depth of allusion in every chapter and the exciting eclecticism of the Black Dossier’s influences.

While the first two volumes of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen told straightforward tales of national—or worldwide—danger and the odd, ripped-from-the-pages-of-public-domain-fiction heroes’ attempts to defeat the looming threat, the Black Dossier is fragments of the past, present, and future (well, the future of the characters presented in The League volumes one and two, anyway) interspersed with a framing story involving James Bond, Emma Peel, and the pursuit of Mina Murray and a rejuvenated Allan Quatermain as they seek refuge in the realm of imagination.

The Black Dossier is part discovery of the dossier in the title—which provides playful and sometimes ribald glimpses into the history of the team—and part climax and conclusion to the phase of Alan Moore’s career embodied by “America’s Best Comics.” The final sequence of the book recalls the end of Promethea and the world-ending apocalypse-and-rebirth of Tom Strong, even though it doesn’t really crossover with the specific events of either series. It’s more of a spiritual companion, and the spirit is drenched in the waters of the Blazing World.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier (Wildstorm/America’s Best Comics, 2007)

I suspect one of the reasons that the Black Dossier was less-well-received than previous installments of The League was that the references to past works of literature and popular culture were not only more densely packed—and more overtly the purpose of the text instead of merely being potent subtext—but that they were decidedly more obscure. Most of the allusions in this volume are not part of the cultural consciousness in the same way we all know the basics of Dracula, War of the Worlds, or 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Here, the allusions seem particular to a specific generation of 50-something well-read adults raised in Britain on a steady diet of comics both weird and popular, the history of fantastical occultism, Jack Kerouac, William Shakespeare, Enid Blyton, and the pornographic tradition in the English language. In other words, allusions specific to the memories and interests of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, with enough recognizable-but-not-specifically-named characters from pop culture that it all mostly makes sense without being Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, but those annotations from Jess Nevins and friends are more useful here than they are with any previous comic book ever published.

The framing story in the Black Dossier flirts with copyright infringement, pushing into the mid-20th century where public domain characters are rarer, and so we get a James Bond who is known merely as “Jimmy,” a vicious womanizer with a connection to a sleazy character Mina and Allan worked with in the adventures detailed in previous volumes of the series. We also get a supporting appearance by Emma Peel, and a bit of humorous insight into the secret origin of her famous catsuit. In addition, the flight of Mina and Allan takes them to the kind of space-ready corners of Britain as shown in the likes of Dan Dare, and a central bit of investigation takes the protagonists to Greyfriars, where they meet an aged Billy Bunter, star of page and screen.

At first, the appearance of Mina Murray and Allan Quatermain is disorienting, and it takes a bit of reading to piece the backstory together. (Well, Moore gives it to us via a prose piece later in the volume, so it doesn’t take much brainpower to figure it out, but it does take some patience.) Though the young woman who appears in the opening scene sports a modest blue scarf, in her dalliance with Jimmy Bond, she’s not immediately recognizable as our Miss Mina, because her hair is a vibrant blond and she’d surely be an old woman 50-plus years after the Martian episode from the previous volume. And she goes by the ridiculous James Bondian femme fatale name Odette “Oodles” O’Quim. But she is indeed Mina Murray, and the retrieval of the “Black Dossier” is her goal.

Allan Quatermain’s appearance is even more baffling, at first. Mina had abandoned Allan by the end of The League’s second volume, but here she is accompanied by a young man she clearly shares a history with. It turns out to be a fountain-of-youth-ified Allan, and the two young-beyond-their-years protagonists spend most of the Black Dossier on the run, reading sections of the dossier itself at various stops along the way. Because the overarching structure of the book is one of flight rather than conflict, climax, resolution, it is a less traditionally satisfying story than volumes one and two. That is surely one of the causes of its less-than-eagerly-embraced reception. It isn’t much of a story, if you just read the Mina and Allan bits. It’s clever fun, but not substantial.

Instead, the substance of the Black Dossier comes from its accumulation of manufactured artifacts. Your pleasure in reading those sections entirely depends on how successful you find Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill (though mostly Alan Moore, since there are several prose or verse sections that rely more on words than images) in their parodic modes. I find them extremely successful, and I’d rate the Black Dossier as one of the most substantial and interesting works out of the entire Alan Moore oeuvre.

Moore loads the book with pastiches, and writes all of them in appropriately different voices. He doesn’t just take inspiration from, or borrow, works of literature and characters from the past, he channels them with one gleeful wink after another. From the Aleister-Crowley-by-way-of-Somerset-Maugham dry seriousness of the “On the Descent of the Gods” excerpt to the indignant-but-jaunty espionage memoir of Campion Bond, to the awkwardly decorous crossover with Jeeves and Wooster, Moore provides a larger context for the adventures of Mina Murray and company while riffing on literary modes that have fallen out of fashion, but were once burdened with cultural weight.

The Black Dossier has this in common with the rest of The League episodes: it presents itself as a deadly serious chronicle of absurdly hilarious situations. For all of its self-indulgent, pretentious, allusive, exciting eclecticism, the Black Dossier is a relentlessly amusing book.

In “TRUMP featuring ‘The Life of Orlando,’” the first substantial comic-within-a-comic found in the Black Dossier, the League gets a lengthy backstory by way of Virginia Woolf’s gender-shifting protagonist. Orlando is the de facto third member of the League by the time of the Black Dossier’s framing story, but the long-lived one is mostly seen in this comical retelling of his/her life story. By the time Mina and Allan meet up with Orlando in the book’s final sequence, they are ready to face the future in the follow-up volume: Century.

Do I need to say, “but wait, there’s more!?!?”

Because I just did.

Moore also gives us a parody called Faerie’s Fortunes Founded which is closer to the Shakespeare of The Merry Wives of Windsor than the Shakespeare of Hamlet. In lively iambic pentameter, we meet the equivalent of the Elizabethan League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, working for Gloriana, the “faerie queen” of Edmund Spenser’s famous epic. This crop of secret agents includes yet another Bond ancestor, alongside Orlando and The Tempest’s Prospero. It is Prospero himself who will later give the final speech in The Black Dossier, via his pulpit in the Blazing World of the narrative present, with a little help from ancient 3D technology.

But Moore includes other humorous moments before we get to the book’s closing pages. He describes, via official-sounding reports, accompanied by wonderful Kevin O’Neill illustrations, the failed attempt by the French government in creating a League of their own in a section called “The Sincerest Form of Flattery.” And in “The Warralston Team,” we hear about a pathetic and short-lived attempt by the British to replicate their League success with a group of third-stringers who vaguely fit the archetypes embodied by Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, Mr. Hyde, Captain Nemo, and the Invisible Man. These third-stringers come from lesser-known works of literature and fail in every aspect to live up to the quasi-functionality of the originals.

Before Moore and O’Neill return to finish off the frame story and bring the protagonists into the Blazing World, based on Margaret Cavendish’s imaginative work of 1666, Moore gives us one last prose tour-de-force, via Sal Paradyse’s The Crazy Wide Forever, in which the author does a hyperkinetic Jack Kerouac impression channeling that writer’s Doctor Sax novel, mixing it in with H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos, and throwing in the members of Mina Murray’s mid-century League. The text is dense with wordplay and metaphor and works most powerfully when read aloud as a kind of beat-era invocation to the multi-dimensional elder gods. It invites participation in its oppressively alliterative poetry.

Those fragments—pseudo-Shakespearean, almost-Kerouacian, part-Virginia Woolf, and part-Ian Fleming—are what matter in the Black Dossier. At least until the end, when Mina and Allan reunite with Orlando in the Blazing World (as the reader is asked to put on 3D glasses to get the full effect of the old-fashioned blue-and-green doubling), and Prospero gives a final speech to the characters, and to the reader.

Prospero, the old sorcerer, the character most often interpreted as a literary representation of Shakespeare’s farewell to the dramatic arts, here seems to speak on behalf of Alan Moore, in celebration of imagination’s power, speaking from the utopian world where creativity reigns, a version of Plato’s world of forms, or Kant’s noumenon, or Promethea’s Immateria:

“Rejoice! Imagination’s quenchless pyre burns on, a beacon to eternity, its triumphs culture’s proudest pinnacles when great wars are ingloriously forgot. Here is our narrative made paradise, brief tales made glorious continuity. Here champions and lovers are made safe from bowdlerizer’s quill, or fad, or fact.” Prospero, bearded and tall, wearing green and red glasses of his own, concludes with “Here are brave banners of romance unfurled…to blaze forever in a Blazing World!”

You can take off your 3D glasses as you exit the comic book.

NEXT TIME: Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill jump ahead through time, and over to another publisher, and give us a look at The League across an entire Century.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.