If there’s one central fact of Stephen King’s existence it’s this: he likes to write. The man has a genuine enthusiasm for putting words on the page that other bestselling novelists just don’t seem to share. J.K. Rowling appears to be almost exclusively focused on the world of Harry Potter and moving slower all the time, George R.R. Martin produces words the way most people pass kidney stones, and James Patterson farms out his writing to co-authors. But Stephen King genuinely enjoys sitting down every day and writing. He once gave an interview saying he writes every day except Christmas and his birthday. Later, he admitted that he actually works on those days, too.

This re-read covered 12 books King wrote in the first ten years of his career. Over that same period, he also wrote another novel, The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger; the short illustrated story, Cycle of the Werewolf; the long novella, The Mist; co-authored The Talisman with Peter Straub; wrote the screenplay for Creepshow; produced Danse Macabre, a book length non-fiction survey of horror; and turned out over a dozen short stories. He was writing so much that he even invented a second name, Richard Bachman, so that he could publish more books under another identity. Which didn’t necessarily turn out to be a good thing.

After the film version of Carrie came out in 1976 and sent King’s sales figures soaring, he decided that he wanted his earlier unpublished novels to see the light of day. He had three of them in his trunk and so he started trying to find a way to get them published. Doubleday had made it clear that they didn’t want to saturate the market by publishing more than one Stephen King book per year, so King sent Getting It On, the first book he’d sent to Doubleday, over to his paperback publisher, New American Library, telling them that he wanted to publish it under the name Guy Pillsbury. Elaine Koster, his editor, was delighted but as the manuscript passed around the house word leaked that it was by King. Irritated, King took it back and made some changes.

After the film version of Carrie came out in 1976 and sent King’s sales figures soaring, he decided that he wanted his earlier unpublished novels to see the light of day. He had three of them in his trunk and so he started trying to find a way to get them published. Doubleday had made it clear that they didn’t want to saturate the market by publishing more than one Stephen King book per year, so King sent Getting It On, the first book he’d sent to Doubleday, over to his paperback publisher, New American Library, telling them that he wanted to publish it under the name Guy Pillsbury. Elaine Koster, his editor, was delighted but as the manuscript passed around the house word leaked that it was by King. Irritated, King took it back and made some changes.

First, he retitled it Rage, then he changed his pseudonym to Richard Bachman, a combination of Richard Stark (the pseudonym Donald Westlake uses for his Parker novels) and Bachman-Turner Overdrive, whose album he was listening to at the time. His agent, Kirby McCauley sent the book back to NAL with the condition that no one was to know King was the author. Koster agreed, they published the book, and it died on the shelves. Released two months after King left Doubleday for NAL, Rage told the story of an armed teenager who takes over his high school classroom. The FBI has contacted King in the past when the book has been cited as a favorite of school shooters, and because of this King has let it go out of print.

But King had three more novels in his trunk, all of them written before Carrie, and there was no reason not to continue releasing them. There was The Long Walk, a sci-fi story about a future where a grueling marathon walk is a public spectacle; Roadwork, about a man who has an armed stand-off with the police when his house is slated for demolition in a road building project; and The Running Man, another science-fiction story, this one about a massive manhunt staged as televised entertainment. The most popular of the bunch, The Long Walk, came out right after The Stand was released and it’s had three printings. Roadwork came out after Firestarter, and The Running Man was issued between Creepshow and Different Seasons. None of them sold very well.

But King had three more novels in his trunk, all of them written before Carrie, and there was no reason not to continue releasing them. There was The Long Walk, a sci-fi story about a future where a grueling marathon walk is a public spectacle; Roadwork, about a man who has an armed stand-off with the police when his house is slated for demolition in a road building project; and The Running Man, another science-fiction story, this one about a massive manhunt staged as televised entertainment. The most popular of the bunch, The Long Walk, came out right after The Stand was released and it’s had three printings. Roadwork came out after Firestarter, and The Running Man was issued between Creepshow and Different Seasons. None of them sold very well.

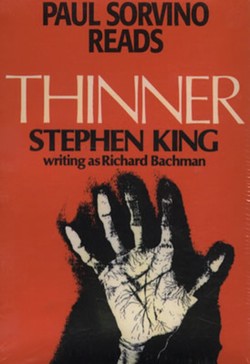

Finally, in 1983, King asked NAL if they would publish his new Bachman book, Gypsy Pie, in hardcover for once and put some marketing money behind it. Since King was making them millions, NAL agreed to indulge him. The title was changed to Thinner and NAL’s marketing team gave away thousands of copies at the Annual Booksellers Convention, and printed 50,000 hardcover copies, the biggest first run for Bachman yet. The reviews were good but the book was no hit, selling only 28,000 copies.

Then, Stephen Brown, a bookstore clerk in Washington DC, got suspicious. He felt Bachman’s writing style was incredibly close to King’s, so one lunch hour he headed over to the Library of Congress and checked the copyright info. All of Bachman’s books were registered to King’s agent, Kirby McCauley, which wasn’t any kind of smoking gun, so Brown kept pushing. Eventually he was shown the original copyright paperwork for Rage and there it was: copyright Stephen King, Bangor, ME. He wrote a letter to King and two weeks later got a call at the bookstore: “Steve Brown? This is Steve King. All right. You know I’m Bachman. I know I’m Bachman. What are we going to do about it? Let’s talk.” Thus began a three-night interview between Brown and King that Brown eventually published in the Washington Post. Even though Entertainment Tonight and the Bangor Daily News also broke the story, Brown’s piece in the Post was the only one featuring an extended interview with King himself. Despite saying that he was “pissed” to be exposed, King couldn’t argue that it was an entirely bad thing. Sales of Thinner jumped from 28,000 copies to 231,000.

Then, Stephen Brown, a bookstore clerk in Washington DC, got suspicious. He felt Bachman’s writing style was incredibly close to King’s, so one lunch hour he headed over to the Library of Congress and checked the copyright info. All of Bachman’s books were registered to King’s agent, Kirby McCauley, which wasn’t any kind of smoking gun, so Brown kept pushing. Eventually he was shown the original copyright paperwork for Rage and there it was: copyright Stephen King, Bangor, ME. He wrote a letter to King and two weeks later got a call at the bookstore: “Steve Brown? This is Steve King. All right. You know I’m Bachman. I know I’m Bachman. What are we going to do about it? Let’s talk.” Thus began a three-night interview between Brown and King that Brown eventually published in the Washington Post. Even though Entertainment Tonight and the Bangor Daily News also broke the story, Brown’s piece in the Post was the only one featuring an extended interview with King himself. Despite saying that he was “pissed” to be exposed, King couldn’t argue that it was an entirely bad thing. Sales of Thinner jumped from 28,000 copies to 231,000.

The Bachman episode would provide inspiration for King’s book The Dark Half, in which an author’s pseudonymous identity comes to life and torments him, but otherwise Bachman was dead. King would revive him again in 1996 for a new novel, The Regulators, and he would also release his last trunk novel, Blaze, in 2007 under the Bachman name. But, for the most part, King was done with Bachman, and that’s a good thing.

Thinner, released in 1984, is the only Bachman book besides The Regulators that didn’t start out with the name Stephen King on the manuscript. Unlike the other Bachman books it’s not science fiction or a thriller, it’s pure horror, but it shares DNA with the other Bachman books, including a grim, downbeat ending. King always went out of his way to give his books happy endings, but not the Bachman books. They were a place where he didn’t need to worry about his readership and could indulge his fantasy of being a penny-a-word pulp writer (namely Donald Westlake). Unfortunately, an author play-acting as another author isn’t a very satisfying thing, and while the Bachman books are all perfectly enjoyable reads, they books don’t hold up particularly well next to King’s other books. Thinner, in particular, is extremely weak.

Thinner, released in 1984, is the only Bachman book besides The Regulators that didn’t start out with the name Stephen King on the manuscript. Unlike the other Bachman books it’s not science fiction or a thriller, it’s pure horror, but it shares DNA with the other Bachman books, including a grim, downbeat ending. King always went out of his way to give his books happy endings, but not the Bachman books. They were a place where he didn’t need to worry about his readership and could indulge his fantasy of being a penny-a-word pulp writer (namely Donald Westlake). Unfortunately, an author play-acting as another author isn’t a very satisfying thing, and while the Bachman books are all perfectly enjoyable reads, they books don’t hold up particularly well next to King’s other books. Thinner, in particular, is extremely weak.

Billy Halleck is a high end lawyer in Chicago who is also an obese compulsive overeater. After accidentally running over an elderly gypsy woman he’s acquitted on the charge of vehicular manslaughter by a judge who is a personal friend, and a cop who lets the investigation slide. On his way out of the courtroom, the dead woman’s father touches Halleck’s cheek and whispers “Thinner.” Immediately afterwards the pounds start to drop from Halleck and, while he enjoys it at first, it quickly becomes life-threatening. After discovering that the judge is in hiding because he’s growing hard scales all over his body and that the cop’s face has been reduced to a bowl of bloody oatmeal by a virulent outbreak of acne, Halleck decides to find the gypsies and make them remove the curse.

As his weight drops to a life-threatening point, Halleck asks his old mobster friend, Richie Ginelli, for help and this is where the book becomes King’s version of one of Westlake’s Parker novels. Told in a clipped, spare style, with every swapped license plate and hotwired car described in flat, relentless detail, Ginelli puts remorseless pressure on the gypsies as he wages a war of wills with them. Thinner becomes a Parker novel for people who don’t read Parker, and it feels about as authentic as Marie Antoinette dressing up as a shepherdess to play peasant. After a long series of pulp maneuverings, the gypsies relent and remove Halleck’s curse and put it into a pie, telling him that it will be passed on to the next person who eats it. Halleck wants to feed it to his wife, whom he feels has not stood by him through this ordeal, but when he gets home he throws the pie in the fridge and goes to bed. When he wakes up, he’s horrified to find that his daughter has had a slice. All sad, Halleck cuts himself a piece, too.

As his weight drops to a life-threatening point, Halleck asks his old mobster friend, Richie Ginelli, for help and this is where the book becomes King’s version of one of Westlake’s Parker novels. Told in a clipped, spare style, with every swapped license plate and hotwired car described in flat, relentless detail, Ginelli puts remorseless pressure on the gypsies as he wages a war of wills with them. Thinner becomes a Parker novel for people who don’t read Parker, and it feels about as authentic as Marie Antoinette dressing up as a shepherdess to play peasant. After a long series of pulp maneuverings, the gypsies relent and remove Halleck’s curse and put it into a pie, telling him that it will be passed on to the next person who eats it. Halleck wants to feed it to his wife, whom he feels has not stood by him through this ordeal, but when he gets home he throws the pie in the fridge and goes to bed. When he wakes up, he’s horrified to find that his daughter has had a slice. All sad, Halleck cuts himself a piece, too.

Thinner bears some of King’s unmistakeable stylistic trademarks, especially his tendency to interrupt sentences with italicized sentence fragments, reducing the Bachman identity to a disguise as thin as Clark Kent’s glasses. But, deprived of the responsibility of having his name on the cover, the book freed King to take less care, and the hallmark of Stephen King has always been the care he takes. King researches his subjects meticulously (how many people learned a lot about cars from Christine?), he takes the time to find the good in all of his characters, even his monsters, and he takes the care to inject his stories with a lot of literary ambition.

Thinner bears some of King’s unmistakeable stylistic trademarks, especially his tendency to interrupt sentences with italicized sentence fragments, reducing the Bachman identity to a disguise as thin as Clark Kent’s glasses. But, deprived of the responsibility of having his name on the cover, the book freed King to take less care, and the hallmark of Stephen King has always been the care he takes. King researches his subjects meticulously (how many people learned a lot about cars from Christine?), he takes the time to find the good in all of his characters, even his monsters, and he takes the care to inject his stories with a lot of literary ambition.

Cujo plays a long game with chance and coincidence that is the equal to anything considered literary fiction, and there are few authors who have revealed as much about their fears as King did in The Shining. Brett Easton Ellis may have thought he was breaking new ground with American Psycho, but King had found sympathy for the Devil years earlier with The Dead Zone. Without this level of care, without this attention to detail, without this ambitious striving to be more than “just” entertainment, we’re left with a readable book that’s a second-hand imitation of Donald Westlake. No matter how readable Thinner is, in the end it’s just a game of dress-up.

The book is heavy on guilt and responsibility, which was a theme King had previously explored in Pet Sematary, and it also contains a taste of Cujo’s themes of life being made up of a web of interconnected events. But whereas these deep thoughts were woven into every strand of Cujo and Pet Sematary, in Thinner they are literally spelled out when Halleck writes a letter to his wife saying, “When you look at things closely you start to see that every event is locked onto every other event…to believe in the curse is to believe that only one of us is being punished for something in which we both played a part. I’m talking about guilt avoidance…” The scene may as well have a sign over it: this is the book’s theme, start your interpretive essay here.

The book is heavy on guilt and responsibility, which was a theme King had previously explored in Pet Sematary, and it also contains a taste of Cujo’s themes of life being made up of a web of interconnected events. But whereas these deep thoughts were woven into every strand of Cujo and Pet Sematary, in Thinner they are literally spelled out when Halleck writes a letter to his wife saying, “When you look at things closely you start to see that every event is locked onto every other event…to believe in the curse is to believe that only one of us is being punished for something in which we both played a part. I’m talking about guilt avoidance…” The scene may as well have a sign over it: this is the book’s theme, start your interpretive essay here.

There’s a sloppiness throughout the book, and King admits to it when he says that for the gypsy’s Romany dialogue he simply lifted random lines from the Czech editions of his books, but that’s the least of it. After several chapters showing Ginelli behaving like an indestructible badass, Halleck leaves him in his car for 20 minutes and returns to find nothing but Ginelli’s severed hand. Apparently this unstoppable Terminator has been killed in broad daylight by a young gypsy woman and his body has been…eaten? Burned? Tucked away in a kangaroo’s pouch? Who knows? It’s equally improbable that after so much time and agony spent procuring Halleck’s gypsy pie, he would simply toss it in the fridge and go to bed. But why should King care if his name isn’t on the cover? Especially if he’s having so much fun pretending to be Donald Westlake?

There’s a sloppiness throughout the book, and King admits to it when he says that for the gypsy’s Romany dialogue he simply lifted random lines from the Czech editions of his books, but that’s the least of it. After several chapters showing Ginelli behaving like an indestructible badass, Halleck leaves him in his car for 20 minutes and returns to find nothing but Ginelli’s severed hand. Apparently this unstoppable Terminator has been killed in broad daylight by a young gypsy woman and his body has been…eaten? Burned? Tucked away in a kangaroo’s pouch? Who knows? It’s equally improbable that after so much time and agony spent procuring Halleck’s gypsy pie, he would simply toss it in the fridge and go to bed. But why should King care if his name isn’t on the cover? Especially if he’s having so much fun pretending to be Donald Westlake?

The result is a book that feels thinner (no pun intended) than King’s better books. Richard Bachman is King without his voice, and the result is flat. Rather than bringing a touch of literary aspirations to the horror novel, Bachman dumbs King down. Thinner is entertaining the way an EC horror comic is entertaining, but it’s not much more than that. There’s a reason it didn’t sell on its own: because it was no different than a million other mass market horror paperbacks with cutaway covers that were clogging up drugstore racks across the country.

Thinner aside, re-reading all these Stephen King books has been a pleasure and a surprise. I’ve been surprised at the way some of the books I never loved turned out to be so ambitious, and how some of the books that I clung tightly to as a teenager wound up leaving me empty (‘Salem’s Lot, I’m looking at you). If I had to go through the list and pick the books that disappointed me the most, in order of greatest disappointment to least, they’d have to be:

Christine—if King ever wrote a book that felt like a quick cash-in attempt, this is it.

Thinner—it’s King without the things that make me like King. Things like ambition, a love for his own characters, and a determination to take care with his craftsmanship.

‘Salem’s Lot—as much as I loved it as a kid, and as ambitious as it is, I just felt that it didn’t hold up over the years. Today, it feels like a collection of influences rather than a living, breathing novel.

“Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” and “Apt Pupil”—there was nothing wrong with either of these but neither jumped off the page the way I remembered them doing the first time I first read them.

I’m going to leave The Stand off of this list. It’s a book a lot of people feel passionately about, and a book that I read several times in high school. But while I know it speaks to a lot of people, it’s just not for me anymore. That doesn’t mean it’s a bad book (unlike Christine, which is objectively bad) but it’s a book I feel I’ve outgrown. Pet Sematary feels the same way to me. As much as I admire what King’s doing, and as successful as I think the book is, it’s not a book I’ll ever think much about again or come back to, not because of any failings on its part, but simply because it’s no longer for me.

The happier surprise for me in this re-read was how many books I loved. Especially during his NAL years, King was pushing hard and trying something new, and it showed. In order of least to greatest, here’s how I felt about the rest of his books:

Carrie—this is one of those books where you understand why people were so excited when it came out. Deeply experimental in form, it also gave us King’s first truly sympathetic monster.

Firestarter—unjustly neglected, King’s most sexual book is also one of his best books about children.

“The Body” and “The Breathing Method”—two stories from Different Seasons that have held up incredibly well. “The Body” remains one of King’s best, and “The Breathing Method” is one of the few times he’s done pastiche so perfectly.

The Dead Zone—it’s sort of breathtaking to me that King was willing to write an entire book about a failed political assassin and still keep the reader on his side all the way through. King calls it his first “real” novel, and he’s not wrong.

The Shining—rarely has an author put his own personal nightmares on the page in this much detail. This is something of a highwire act for King’s own self-loathing, and it works.

Cujo—I was really, really, really surprised I liked this one so much. It’s everything that’s great about King and almost nothing that’s not-so-great. Ultimately it’s just the story of a good dog gone bad, but there’s so much more here that I’ve found myself haunted by it weeks later.

And that’s all she wrote. Later I may tackle Misery and It, but this covers the King canon. He may have gone on to write more books, and he may gone on to write better books, but these 12 are the ones on which his fame rests. And it was nice to discover that over half of them not only still hold up, they’re still capable of surprising me. If you’ve never read King, or if you haven’t re-read him in a long time, you could do a lot worse than to pick up Cujo or The Shining and start reading him all over again.

Grady Hendrix has written about pop culture for magazines ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He also writes books! You can follow every little move he makes over at his blog.