As surely as the sun rises in the east, every few years Stephen King will mention retiring, the press will jump on it with both feet, the world will spread far and wide that “The King is Dead”, and minutes later King will have another book on the market that his publishers call “his return to true horror.” In 2002, King told the LA Times he was retiring while promoting From a Buick 8. After about 15 minutes, Stephen King was back, and this time it was with a zombie novel dedicated to George Romero and Richard Matheson, and Scribner was thrilled that their multi-million investment in King was paying off with a new horror novel.

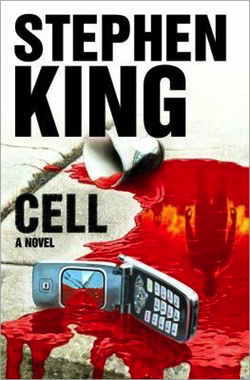

They printed 1.1 million copies and, to promote it, they got Nextones to send texts asking people to join the Stephen King VIP Club where they could buy $1.99 Cell wallpapers for their mobile phones and two ringtones of King himself intoning, “It’s okay, it’s a normie calling.” and “Beware. The next call you take may be your last.” King wanted it to say, “Don’t answer it. Don’t answer it,” but Marketing nixed that idea. The result? Parent company Simon & Schuster got sued for unsolicited telephone advertising in Satterfield v. Simon & Schuster to the tune of $175/plaintiff, or $10 million total. With a price tag like that, good thing Cell is one hell of a 9/11 novel.

King wrote Cell after seeing a woman come out of a New York hotel talking on her cell phone and he wondered what would happen if she heard an irresistible sound compelling her to kill coming in over her phone signal. The idea was clearly a potent one since King wrote it the same year he wrapped up his Dark Tower series and wrote The Colorado Kid. Time from initial idea to book going off to the printer’s? Barely ten months. The speed with which it was written shows in some of the occasionally awkward language (unsuspecting victims “slept in their innocency”), and its eager recycling of earlier King scenes, but the speed also means it’s a visceral reaction to the War in Iraq and 9/11 that hits the page still hot and steaming, like an arterial spray.

Clayton Riddell is bopping along Boylston Street in Boston, a $90 paperweight in hand as a gift to his estranged wife, Sharon, because after years of struggle he’s just sold his first graphic novel, Dark Wanderer, for a lot of money. He’s rewarding himself with an ice cream cone on page five when all hell breaks loose. It’s called The Pulse and it’s a signal that comes through the cell phones and turns everyone who hears it into a rage maniac, kind of like in 28 Days Later only with better network coverage. A woman in a power suit stabs herself in the ear drum with her manicured finger before getting her throat torn out by a teenaged girl. A business man bites off a dog’s ear. A Duck Boat full of tourists drives into a storefront. A young girl smashes her face into a lamppost over and over again, screaming “WHO AM I?”

Clayton Riddell is bopping along Boylston Street in Boston, a $90 paperweight in hand as a gift to his estranged wife, Sharon, because after years of struggle he’s just sold his first graphic novel, Dark Wanderer, for a lot of money. He’s rewarding himself with an ice cream cone on page five when all hell breaks loose. It’s called The Pulse and it’s a signal that comes through the cell phones and turns everyone who hears it into a rage maniac, kind of like in 28 Days Later only with better network coverage. A woman in a power suit stabs herself in the ear drum with her manicured finger before getting her throat torn out by a teenaged girl. A business man bites off a dog’s ear. A Duck Boat full of tourists drives into a storefront. A young girl smashes her face into a lamppost over and over again, screaming “WHO AM I?”

Unseen explosions rock Boston, and the violence zooms out to show columns of smoke rising over the city, and zooms in to show Clayton fighting for his life against a businessman with a chef’s knife. It’s a beautiful 30-page setpiece of a normal day going to hell fast and hard, just like it did on 9/11, or any average Thursday in Fallujah. The climax comes as Clayton and another man cooperate to get away from the carnage and run up against a uniformed police officer calmly executing one lunatic after another, putting his gun to their skulls, and POW! Clayton and Tom McCourt freeze in horror as the cop subjects them to a bizarre interrogation (“Who is Brad Pitt married to?”) then hands them his business card, saying, “I’m Officer Ulrich Ashland. This is my card. You may be called upon to testify about what just happened here, gentlemen.” But there will be no testimony, no more trials, no more society. When trouble hits, you pick up your cell phone, but here the cell phones themselves are the trouble. It takes less than a week for society to break down into roaming packs of berserk “phoners” flocking together to feed and sleep. Tom McCourt, Clayton Riddell, and a teenaged girl named Alice are among the few normal survivors, and they head north to Maine to find Clayton’s son, Johnny, who may or may not have been on his cell phone when the Pulse hit.

“You get to a point where you get to the edges of a room, and you can go back and go where you’ve been, and basically recycle stuff,” King said in 2002 about why he wanted to retire. “I’ve seen it in my own work.” And it’s definitely here. King’s done the Men on a Mission book before, whether it’s the quest to Las Vegas undertaken in the last third of The Stand, or the journey to Colorado in the first half of that book. Whether it’s the boys of “The Body” making a trek up the railroad tracks to find a missing corpse, the long chase to stop Mr. Gray in Dreamcatcher, or the long walk north to find Johnny in Cell, the epic quest is a King staple. As the trio in Cell move north, they notice the phoners are practicing strange rituals and engaging in odd behavior that indicates they’ve developed a telepathic hive mind and are evolving away from humanity. They even begin to levitate, but as in The Tommyknockers, the more powerful they get the faster they burn out. This isn’t a freak accident, it’s the dawning of a new civilization. The few normal survivors are stranded in a world that has no place for their most precious values. Written in the wake of what was, for a lot of people, the disorienting re-election of President George W. Bush in November 2004, the idea of being a minority out of step with, and unable to understand, the new world around them takes on added resonance.

“You get to a point where you get to the edges of a room, and you can go back and go where you’ve been, and basically recycle stuff,” King said in 2002 about why he wanted to retire. “I’ve seen it in my own work.” And it’s definitely here. King’s done the Men on a Mission book before, whether it’s the quest to Las Vegas undertaken in the last third of The Stand, or the journey to Colorado in the first half of that book. Whether it’s the boys of “The Body” making a trek up the railroad tracks to find a missing corpse, the long chase to stop Mr. Gray in Dreamcatcher, or the long walk north to find Johnny in Cell, the epic quest is a King staple. As the trio in Cell move north, they notice the phoners are practicing strange rituals and engaging in odd behavior that indicates they’ve developed a telepathic hive mind and are evolving away from humanity. They even begin to levitate, but as in The Tommyknockers, the more powerful they get the faster they burn out. This isn’t a freak accident, it’s the dawning of a new civilization. The few normal survivors are stranded in a world that has no place for their most precious values. Written in the wake of what was, for a lot of people, the disorienting re-election of President George W. Bush in November 2004, the idea of being a minority out of step with, and unable to understand, the new world around them takes on added resonance.

Marinated in the new horror language of 9/11 and the Iraq War, Cell depicts an existential clash of civilizations. There are cell phone detonators and truck bombs, descriptions of bomb blast victims blown out of their shoes that feel transcribed right off CNN, Osama bin Laden and Guantanamo Bay are invoked, and a kid they meet is described as ardent as “any Muslim teenager who ever strapped on a suicide belt stuffed with explosives.” But this isn’t just trendy window dressing. Whether he knows it or not, King is writing about the world of the 2000s when random violence revealed seemingly unbreakable traditions and institutions as weak and ineffectual. The older characters, Tom and Clayton, want to get to Maine, rescue Clayton’s son, and be left alone. They try to negotiate a compromise with the phoners. Alice, and Jordan, another teenager they pick up, know that there can be no compromise. They want to avenge their dead friends and family by wiping out the phoners completely, and King thinks that this makes them better suited for survival.

Marinated in the new horror language of 9/11 and the Iraq War, Cell depicts an existential clash of civilizations. There are cell phone detonators and truck bombs, descriptions of bomb blast victims blown out of their shoes that feel transcribed right off CNN, Osama bin Laden and Guantanamo Bay are invoked, and a kid they meet is described as ardent as “any Muslim teenager who ever strapped on a suicide belt stuffed with explosives.” But this isn’t just trendy window dressing. Whether he knows it or not, King is writing about the world of the 2000s when random violence revealed seemingly unbreakable traditions and institutions as weak and ineffectual. The older characters, Tom and Clayton, want to get to Maine, rescue Clayton’s son, and be left alone. They try to negotiate a compromise with the phoners. Alice, and Jordan, another teenager they pick up, know that there can be no compromise. They want to avenge their dead friends and family by wiping out the phoners completely, and King thinks that this makes them better suited for survival.

Throughout Cell, the old people are useless, hidebound, their ideas don’t work, they pursue silly goals like rescuing cats and trying to protect abandoned boarding schools. The few times they take action the phoners simply laugh at them. It’s Alice and Jordan, the young, bloodthirsty kids, who come up with all the explanations, who are the leaders, who understand that this is a war. Abandoned schools and unemployed school teachers form a depressing backdrop to the action, and it’s no accident that the mission of mercy to find Clayton’s son morphs into a suicide bombing run. Cell ends with a scene right out of the end of “The Mist” as a father attempts a rescue of his son, the outcome left unclear.

The book received decent reviews when it came out, although oddly enough the New York Times ran a positive review by Janet Maslin in January, then a snarkier one by Dave Itzkoff a week later. Sales were decent, with Cell debuting in the number one spot on the New York Times bestseller list, and remaining there for three weeks before James Paterson and Maxine Paetro’s The 5th Horseman knocked it down to number two, starting a steady slide down the chart, where it dropped off completely after ten weeks. With its recycled ideas and its small scale quest, there’s something exhausted about Cell, but that fits with the horrifying picture King paints of a tired, dusty, moribund world becoming the battleground between two bloodthirsty visions of the future that will accept no compromise, each dedicated to the total extinction of the other. It’s a war that leaves the schools, museums, fairgrounds, governments, hospitals, companies, and restaurants we’ve spent hundreds of years carefully constructing as nothing more than bloody rubble, ground beneath the feet of the new combatants in this endless war.

The book received decent reviews when it came out, although oddly enough the New York Times ran a positive review by Janet Maslin in January, then a snarkier one by Dave Itzkoff a week later. Sales were decent, with Cell debuting in the number one spot on the New York Times bestseller list, and remaining there for three weeks before James Paterson and Maxine Paetro’s The 5th Horseman knocked it down to number two, starting a steady slide down the chart, where it dropped off completely after ten weeks. With its recycled ideas and its small scale quest, there’s something exhausted about Cell, but that fits with the horrifying picture King paints of a tired, dusty, moribund world becoming the battleground between two bloodthirsty visions of the future that will accept no compromise, each dedicated to the total extinction of the other. It’s a war that leaves the schools, museums, fairgrounds, governments, hospitals, companies, and restaurants we’ve spent hundreds of years carefully constructing as nothing more than bloody rubble, ground beneath the feet of the new combatants in this endless war.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.

I think this was the last mainline King book I read, with the exception of Dr. Sleep. Still have copies of Lisey’s Story and Duma Key sitting on the shelf; guess I have some catching up to do …

I always thought this was a comic book of a novel – no accident the main character is a graphic novellist! That’s not an insult to the book; it’s a fast, fun, exciting read. We’ve even got the “stock” characters: the Good Father, the Wise Old Academic, the Scrappy Teen, etc. The book is fast-paced and has lots of action and gore. I know King loved comics as a kid (especially EC comics) and this reads like one.

The first time I read “Cell,” some of the political commentary went over my head. However, Grady, I think you’re 100% right about “Cell” being a 9/11 novel. The Boston scenes are not a bad imagining of what things might have been like had the planes crashed into the John Hancock building in Boston rather than the Twin Towers. I live in NYC now, but on 9/11 I lived just north of Boston. I remember the chaos and panic – people *were* almost running around asking “Who am I?” in the wake of the attacks. Reality was destablized in a way I hadn’t known in my personal lifetime – as it is in “Cell.”

There is a nice nod to George Romero when King writes the leader of the phoners as a Black man (I’m not sure if the Harvard shirt is King taking the p!ss out of the Ivy League as a public college graduate himself.) However, the racial politics of that character are less nice. I understand that King has had ongoing trouble with writing non-stereotyped and realistic people of colour in his work. He’s admitted so himself. I know that Maine is, statistically, THE whitest state in the entire U.S. and King’swriting is very obviously informed by his life there. It’s just more than a little jarring to have the “Big Bad” in this novel be a Black man, wearing a shirt with the name of a college that historically has excluded and been biased against people of colour. Unless this is a meta-textual commentary about the terrible racial profiling and racial politics in the wake of 9/11…?

I, personally, would have loved a ringtone of Stephen King’s voice saying, “Don’t answer it!” :)

Interesting bit that only those who know New Hampshire will catch:

the town in NH with a prep school where Our Heroes stop, on their way up route 28, is clearly Derry NH, home of Pinkerton Academy and on route 28. King must have changed the name because “Derry” is also the name of his fictional Maine town.

@jmeltzer: Haha – I missed that one! I grew up in Massachusetts and I know exactly where that is. I’m quite sure the “Derry” connexion is on purpose! ;)

I think it’s an okay enough book until the end, myself. The problem I have (alluded to in a comment in the Colorado Kid thread) is King’s unwillingness to fully accept the inevitable nasty ending he’s worked himself into, which in turn leads to him pulling out a cliche–one satirized in an early South Park episode, “Pinkeye”–that basically undermines everything that preceded the conclusion.

It’s the cure for zombie, in other words, with the revelation of that cure retroactively rendering most of the main characters’ actions up until the end a series of completely gratuitous atrocities. Which, actually, could be a different and maybe better book, but almost as soon as this bombshell is dropped upon us the book comes to a vaguely hopeful cliffhanger end; while we don’t know if the zombie cure will work on the hero’s son, we’re supposed to be focused on hoping that it will instead of worrying about the massive slaughter of people who might have been treated instead of blown into bits like mindless beasts.

Your mileage may vary, of course. For me, it just didn’t work very well, especially when I realized the ending we were reaching–“If you do this magical one thing, people will go back to normal–if you haven’t been recklessly dismembering and murdering them, that is!”–was one that had been effectively mocked by a group of animated foul-mouthed children. (I could describe the whole thing, but it’s probably funnier to watch. They had a good time with the genre, actually.)

What does kind of work is that this book, From A Buick 8, and Colorado Kid arguably launched the current phase of King’s career, which has featured some of King’s sharpest writing even if some of the longer works have been inconsistent. While I would continue to argue that Cell is unfortunately a bit thoughtless in its conclusion and execution, it’s nevertheless thoughtful in its engagement with the world. King has been evolving into a deeper writer, which may seem odd for an author so infatuated with pulp over the course of his career, but his experiments in trying to fuse his pulpier instincts with literary sensibilities have produced some really interesting (even if not always successful) work. So this is pleasing, at least.

@eric: I’m guessing you liked the ending of “Revival?” ;)

IMHO, King is a Romantic (in the Keatsian sense, not the Harlequin sense.) Although he writes and is drawn to horror, many of his tales are less “dark” than those of other horror writers like Lovecraft and Poe. I think King ultimately believes in the triumph of light over darkness, especially as he’s gotten older. (Compare the ending of “Pet Sematary” to the ending of “Under the Dome,” for example.) I agree that Kingmay sometimes write himself into a corner. I’d also argue that the Romantic sensibility is entwined with and struggles with the conventions of gothic horror (just look at a lot of Coleridge’s and Keats’ poems) – but that’s an ENTIRE other discussion and probably a book in and of itself!

@jaimew I don’t know if you’re being ironic or not, but do you know: I’m one of the few people I know who really loved Revival. And yeah, I liked the ending! :D

Nope, not being ironic – I don’t want to post spoilers but I think King really “followed through” with the premise of his story there. (“Revival” is one of my favourite recent King novels.)

I also really loved his short story “N” – another time when I think he really followed the story to the dark and nihilistic place it led. I do not have OCD, but the idea that “counting” things fixes them in reality is really chilling to me.

Ditto on “N”!

Quite appropos that someone mentioned a comic book plot.

Warren Ellis had a similar idea in his series “Global Frequency” issue story titled “Invasive”.

http://observationdeck.kinja.com/comics-past-global-frequency-3-invasive-1792526099

It was published in 2003.

Hi Grady,

I have a wee request. Would you mind letting us know what book you’ll be reading next (or posting a link to a master list)? I’d love to “refresh” my memory of the book in question each week

Thanks so much in advance!

-Jaime

@11, since Grady is going in chronological order, it should be Lisey’s Story.

@1, hoopmanjh

Both Lisey’s Story and Duma Key remind me of Rose Madder.

It’s good to see Cell being given some attention beyond its usual ranking in “Worst of King” lists. For me, Cell was a return to King after not having read him for nearly 15 years. Though far from perfect, it’s compelling in its depiction of a world falling apart, and it captures the mad violent thrashings of post-9/11 America in a tight (for King) narrative arc. It’s definitely worth reading.