It’s a given: new technology is always better than old technology. And even if it were not, it’s our duty to the economy to purchase the new shiny.

Only a reactionary would object to ticket scanners merely because they are much slower than the bespectacled eye. Or object to mandatory software upgrades on the specious ground that everything they do, they do less well than the previous release.

Sure, sometimes the new thing is a bit disruptive—but isn’t a little disruption good for us all? At least that’s what the people who stand to profit from disruption tell us….

Let’s examine the contrarian position: newer isn’t always best. And let’s take our examples from science fiction, which is dedicated to exploring the new…and, sometimes inadvertently, showing that the newest thing may not work as intended.

Take the humble tramp spaceship, for example, puttering along at a reasonable 10 meters/second/second. It’s a convenient acceleration because it gives the traveller the same weight as they would have at home, while granting access to the Solar System in mere weeks. Given a little more time, tramp spaceships can even explore the near stars.

The catch: the kinetic energy of these vessels ramps up rapidly, from high to stupendously high. One of Heinlein’s torchships might reach peak velocities of single-digit percents of the speed of light, thus gaining kinetic energy roughly equal to the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Per kilogram.

A responsible crew will of course slow the ship before it approaches anything breakable. But what if you don’t have a responsible crew? What if the ship is crewed by a bunch of kamikaze psychos? Boom.

But, since the plot has to unfold within a human lifetime (usually), authors must posit high-performance ships. They don’t posit crews vetted as thoroughly as any missile silo team, however. They don’t consider the downside of super-speedy propulsion systems because those are not the stories they want to tell.

There have been exceptions. John Varley, in his Thunder and Lightning series, imagined a lone genius who handed the world such a propulsion system. A disgruntled starship crew wanted to see just how big a ding they could put in the Eastern Seaboard with a well-aimed starship… A great big ding, as it turned out.

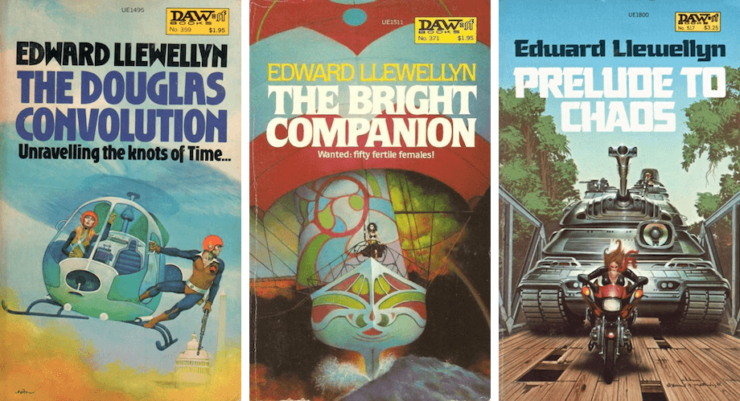

Edward Llewellyn’s Douglas Convolution series (The Douglas Convolution, The Bright Companion, and Prelude to Chaos) imagines the development of a marvellous chemical with applications to chemotherapy, birth control, even insecticides. There was one unexpected consequence: It sterilized females whose mothers had been exposed to the chemical. The world fertility rate plummeted. Societies went extinct, or adapted in nasty ways. But hey, tangerines were cheap before everything collapsed.

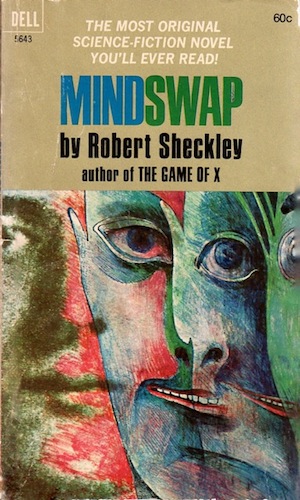

A number of authors have looked at the demands of physical spaceflight and rejected it in favour of less demanding (and as far as we can tell, completely impossible) mental transference. Why send the body when you can just beam (somehow) the contents of someone’s head into a waiting body on the other end?

Robert Sheckley’s absurdist Mindswap provided one answer: you wouldn’t want to do this because mind transfer is a handy tool for the glib conman. Deliver the right line of snappy patter and you could walk away with a healthy new body, while your victim finds himself trapped in a decrepit loaner body.

Richard Morgan’s Takeshi Kovaks stories suggest even darker possibilities; give the rich the ability to gentrify poor people’s younger, healthier bodies and they will. Limit the victims to prisoners…well, who do you think owns the people who write the laws?

On a related note, high-speed communication seems to be getting ever higher speed (subject to the limits imposed by physical law). But what happens when information can be transferred from one person to another so quickly that it becomes hard or impossible to say where one person ends and another person begins? To communicate means to merge.

In Michael Swanwick’s Vacuum Flowers, the backstory is that the entire population of the Earth collapsed into the Comprise mass-mind. Only the humans far away enough from Earth that there is severe communications lag have resisted assimilation. The Comprise cannot function when time lags become too large.

Teleportation seems like it would be pretty darn handy. Step into a booth here, step out half a planet away. In John Brunner’s The Webs of Everywhere (originally published as Web of Everywhere), teleportation devices, called Skelters, proved to be easy to build and therefore impossible to regulate. It took a while for people to realize that there was a downside to making Skelter addresses as public as old-fashioned landline numbers. Consequences: epidemics, terrorism, et cetera. The human population drops to a third of its pre-Skelter level.

Matter duplication would be keen, wouldn’t it? Each sumptuous meal can become a feast for thousands; each car a fleet! As economies are not built to deal with limitless goods, the invention of matter duplication is usually followed by widespread economic and social disruption, as seen in George O. Smith’s classic “Pandora’s Millions.” But Smith’s characters were lucky, because Smith was a comparatively benevolent author. Damon Knight’s A for Anything (also published as The People Maker) pointed out that one could run off lots of copies of useful servants. If one of them rebels…hit the delete key. Lots more where he came from.

A real-life example: I got into book reviewing just about the time ubiquitous cell phones became a thing. Watching mystery writers grapple with the fact that a myriad of stock plots no longer worked if the characters could just reach into their pockets for a phone was quite entertaining. Of course, the downsides of ubiquitous cell phones had been predicted as early as—I bet you all think I am going to mention that scene in Space Cadet where the lead puts his phone in his suitcase to avoid unwanted calls, don’t you?—1919, in this visionary article. Not that it stopped anyone from creating the devices. Which is reassuring, because it means that no matter how many warnings SF authors provide about unintended consequences of technology, we’ll always have to deal with the side effects of tomorrow’s new shinies.

Originally published in May 2019.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.