At the end of The Invention of Fire, the second John Gower mystery by Bruce Holsinger, the aging poet ponders possible outcomes for a pair of fugitives making their way across England. He muses that his friend, Geoffrey Chaucer, would no doubt come up with some cheerful ending in which they live happily ever after, but not Gower, who likes darker tales.

Gower says, “A poet should not be some sweet-singing bird in a trap, feasting on the meat while blind to the net. The net is the meat, all those entanglements and snares and iron claws that hobble us and prevent our escape from the limits of our weak and fallen flesh.”

Holsinger’s novels are about the net.

To a certain extent, all historical novels, especially those about the more remote past, are speculative fiction. We know a lot about late medieval London in the 1380s, the period in which Holsinger sets his novels, but we know very little about Gower’s professional or personal life. These books are filled with an imagined past supported by real events and people, and so offer a pathway into truths that might not be attainable through closer adherence to sources. This is the power of the best historical fiction.

It’s a power we need right now because of the way that the word medieval, in particular, is flung about in a way that says a lot more about us than the past. Expertly crafted historical fiction set in the Middle Ages, even gritty thrillers like Holsinger’s latest, provide an antidote.

There are two ways that the Middle Ages generally get depicted in popular culture—either as packed with lawless and brutish violence, or as filled with fantastic courtly love, chivalric deeds, and a kind of happy paternalism. Both are, of course, nonsense. They make the medieval past into just a flat backdrop against which authors can project their fantasies, whether they be fantasies of shining knights or brutal torture (or both).

Such depictions bleed into popular culture as “medieval,” deployed as a crude pejorative has been increasingly creeping into political writing. ISIS is routinely called medieval (an appellation that’s been debunked). The Ferguson police department is medieval. Russia’s driver’s license regulations are medieval (N.B.: I think they mean Byzantine). These feed off the fictive depictions of shows like Game of Thrones to show the Middle Ages as racked with lawless, savagery, set amidst an environment of rampant filth and disorder. They allow us to impose chronological distance between what ourselves, as modern “good” people,” and what we consider distasteful or horrific.

Holsinger, a professor of medieval literature turned novelist, offers something plenty bloody, but much smarter. Faith, beauty, love, and poetry co-exist with realpolitik, bureaucracy, conspiracy, and vice. In fact, in the Gower thrillers, the former often depend on the latter, a relationship implicit in Holsinger’s selection of John Gower to be our guide. In these books, Gower is presented as a successful peddler of influence and secrets, willing to use the indiscretions of others to line his pockets. And yet, despite his intimate knowledge of the frailty of human morality, the losses he’s experienced in his own family, and increasingly his aging body and failing eyes, Gower is a kind of optimist. He believes he can unravel the lies of the wicked and support those who truly believe in good governance. That surly, world-weary, optimism carries us through the graves, prisons, market, courtrooms, and audience chambers, keeping a little hope that society can withstand the depravities of individuals.

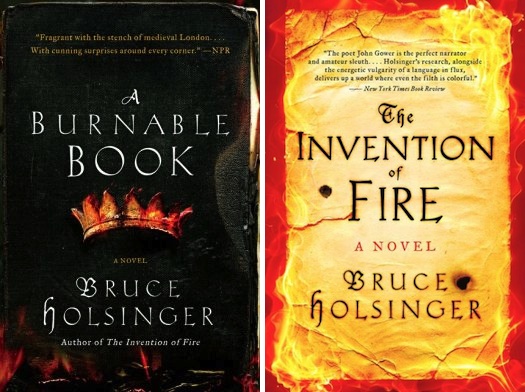

The Invention of Fire begins with sixteen bodies uncovered in the sewers of London, murdered by a cutting edge killing machine called “the handgonne.” John Gower—blackmailer, fixer, poet—is called in by some of the city’s officials to investigate, quietly, and find out what these deaths portend. The story becomes, as was true with his first book, a political thriller in which grave threats to the stability of England must be identified and unwound, villains thwarted, and murderers exposed. The threat of invasion from France, a real terror in 1380s London, looms ominously in the background.

It continues some threads from the previous volume, A Burnable Book, which is based around Holsinger’s creation of a book of prophecy, the Liber de Mortibus Regum Anglorum (The Book of The Deaths of English Kings). The creation of such a volume is treasonous; worse, it might portend actual plots against the crown and threaten to plunge England into civil war and rebellion. The book begins when Gower’s friend, Geoffrey Chaucer, asks him to find the wayward prophetic manuscript. The quest takes the story through the highest and lowest classes of London, as Gower encounters everyone from the consort to the Duke of Lancaster (John of Gaunt) to a “swerver,” the transvestite prostitute Eleanor/Edgar Rykener (based off the documented existence of John/Eleanor Rykener).

To focus on plots, though, as engaging as they are, would be to give Holsinger too little credit. The Gower thrillers use plot as a way to lead the reader into a world that feels at once familiar and distant. The inhabitants of his medieval London are neither barbaric primitives nor merely moderns dressed in burlap, but inhabitants of a richly complex moment all their own. It may not be a place I’d want to live, laden with a savage bureaucracy and an angry church, but Holsinger’s medieval London has become one of my favorite places to visit in all of historical fiction. Moreover, when he lets scene and place fade into the background and imagines Gower and Chaucer discussing poetry, family, and politics, Holsinger’s intense familiarity with the poetic voices of the two authors infuses the dialogue. I’d read a whole book of Gower and Chaucer sitting quietly and discussing things, if Holsinger wanted to write one. He won’t, because both men were too entwined (we think) in the current events of their times, and that tangling spurs the stories forward.

Holsinger’s books live in the net, with all the barbs and snares of a life that transcends the pervasive stereotypes. His books are neither pastoral chivalrous pastiche nor fantasies of mindless savagery, but offer an image of the Middle Ages at once seeming modern and remote. It’s modern because his humans are humans, complex and thoughtful, bodies wracked by time and environment, as real as any character in any fiction in any setting. The remoteness comes from a world based on very different religious, political and material epistemologies than our own. Holsinger’s net captures both the familiar and the strange.

A Burnable Book drips with semen and ink. The Invention of Fire stinks of shit and gunpowder. But I can’t wait for another chance to be ensnared by Bruce Holsinger’s medieval London.

David M. Perry is a freelance journalist and history professor. He writes about disability, police violence, parenting, gender, and history for CNN.com, Al Jazeera America, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and many other sites. Buy his book—Sacred Plunder! Read his blog at How Did We Get Into This Mess? Follow him on Twitter.