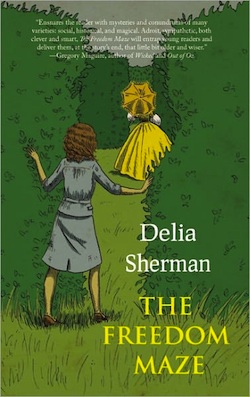

The Freedom Maze, out today from Small Beer Press and available here, is an eloquent and genuinely moving tale of real magic, stories, and the disjunction between Southern myth and Southern reality, circumscribed by time travel and complex trials of identity—racial, familial, gendered, and otherwise. The book, a young adult novel published by the Big Mouth House imprint of Kelly Link & Gavin Grant’s Small Beer Press, is set in the Louisiana of the 1960s and also of the 1860s, on the ancestral plantation land of the Fairchild family to which the main character Sophie belongs.

Sophie has been left at Oak Cottage with her Aunt Enid and her grandmother for the summer while her newly divorced mother goes to college to get her certification to be a public accountant. Her father barely writes after having left them for New York; her mother is demanding and often too sharp with her about her looks, her wits, and her un-ladylike demeanor; her grandmother is worse; only Enid seems to have any care for her. Bereft, upset after a fight with her mother, Sophie makes an ill-considered wish to have a time traveling adventure just like those in her favorite books—and the spirit who she’s been talking to obliges, sending her back one hundred years to her own family’s plantation. Except, in this past, with her darker skin, she’s taken for a bastard child and a slave, and when she tries to impose the narrative of a story-book over her transport and turn it into an adventure, things do not go as expected. There’s no easy trip home, and she has a role to play.

Some spoilers follow.

The Freedom Maze tells a riveting, emotionally resonant story while also working through difficult, multifarious themes about identity and history. The balance between the narrative and the meaning is delicate but perfectly equalized. The story of Sophie’s experience, traveling back in time, trying to survive as a slave, and playing an integral role in the escape of one of her adoptive family before she’s transported back to the present, is interwoven with the story of her coming of age and her explorations of what it means to be family, to be a young woman, to inhabit a potentially or actively dual position in a racially segregated society (both in the 1860s and the 1960s). The Freedom Maze succeeds at every turn in balancing the concerns of telling a great story and telling a story with real meaning.

Sophie is a brilliant protagonist, bright and complex, flawed in believable ways, who provides the necessary point of view to explore all of the issues in which she is positioned centrally—a girl on the cusp of becoming a young woman, considered white in the 1960s but black in the 1860s, stuck in the middle of a splintering family, firmly middle-class but slipping after her mother’s divorce, and confused by her own position in these engagements with the world. Her displacement to Oak Cottage for the summer is the last of these discomfiting uncertainties, as her mother leaves her behind—much like her father did, on going to New York. Her position in the world, at these crossroads of identity and self, is the general place that most coming-of-age stories begin; certainly, the child displaced to a strange old house for a summer or a school semester is a usual jumping off point for magical adventure stories, and Sophie is completely aware of this as a reader herself. The difference is the depth with which Sherman explores her experience in the world, from so many angles of engagement: race, gender, and class above all, but also age, her intellectual estrangement as a curious, book-loving girl and her fractured relations with her family through a divorce. Each of these concerns is explored simply and subtly, worked in with a sentence here and there, a casual observance that speaks to the reader or a turn of phrase that implies volumes.

As one might guess from that description, the source of the balance between rich thematic resonance and narrative momentum is undeniably Sherman’s precise, handsome prose. There is more information packed into this short novel than many writers could fit into a 500-page tome; not a word is out of place or wasted. The linguistic complexity of dialects that Sherman works in, from the contemporary Southern white dialect to the inflections of the yard children in the slave community, is breathtakingly real. The reflection of actual speech and actual life in this novel pulls no punches; Sophie’s experiences at the Fairchild plantation are often wrenching and horrifying, but what that also makes them is real. Prior time travel novels about the period of slavery, like those which Sophie herself is reading at the beginning and using to frame her initial transport into the past, often fail to illustrate the realities of the period, whereas The Freedom Maze is concerned with portraying uncomfortable realities instead of smoothing them over.

The balance between survival and companionship, between the politics of the plantation and the building of new families which both give and need support, between fear and comfort—these realities challenge the myths of Southern “Good Old Days” that Sophie’s own mother and grandmother constantly refer to, as well as myths of the “benevolent master.” As observed in many slave-narratives from which Sherman takes her cues, the act of owning people ruins the potential kindness of the people who do the owning, and makes it literally impossible for them to be actually benevolent.

Africa spoke from the kitchen door. “You both wrong. […] There ain’t no such thing as a good mistress, on account of a mistress ain’t a good thing to be. Think on it, Mammy. Old Missy maybe taught you to read and write and speak as white as her own children. But she ain’t set you free.” (147)

Or, as Sophie and Africa, her mother-figure in the past, discuss:

Sophie knelt down and put her arms around her. ”Mr. Akins is hateful. I’m surprised Old Missy puts up with him.“

Africa wiped her eyes. ”Mr. Akins ain’t nothing but Old Missy’s mean dog. He bite folks so she can keep her name as a kind mistress.” (205)

The racial divides and the ways in which whites dehumanize and abuse blacks in the 1860s are bookended by the ways in which Sophie’s family in the 1960s treat their servants or the people of color they meet in their everyday lives. In the first chapters, Sophie remembers how her mother has told her to avoid and fear black men while they sit in a diner being served by a young black woman, and in the ending chapters she and her Aunt Enid have gone out to shop and are served by a black waitress. Sophie is watching the waitress serving them, and thinks:

“It was very odd, though, to see the waitress lower her gaze when she put down Sophie’s plate and to hear her speak in a soft “white folks” voice, as if she was talking to Miss Liza. Odd and unpleasant. Even painful.

“Quit staring at that girl.” Aunt Enid said when the waitress had gone back into the kitchen. “You’ll embarrass her.”

Sophie felt a flash of anger. “She’s not a girl,” she said. “She’s a grown woman.” (248)

The realities of civil rights in the 1960s juxtaposed with those of slavery in the 1860s are appropriately jarring in their unity—the Fairchilds are still Fairchilds, and as Sophie thinks after her Aunt scolds her for her outburst: “There wasn’t any point in arguing with a Fairchild, even a nice one.” The harsh realities of racial inequality are the frame narrative for a story about the antebellum south in America, and their juxtaposition with each other invites the reader to make similar juxtapositions with the present day, to see what they find immensely lacking. It is a necessarily sobering look at American mythology and the Southern experience across the racial divide, spanning a century with very little actualized change, that calls to mind how much progress we have—or have not—made as of the release of the novel.

Sophie’s multifarious engagements with race are also necessarily complex, and the ways in which the past begins to shape itself around her and affect her reality are fascinatingly, deftly handled. There is the potentially unpleasant aspect of putting a “white” girl into a “black” position to have her experience inequality; avoiding this, we instead have Sophie, who is mixed-race a few generations back, and while she identifies initially as white, her experience in the past alters her view of herself and the world around her. The narrative of history—that she was Robert Fairchild’s illegitimate daughter, that he left her with his brother to go to France, that she was and always had been black and a slave—wends around Sophie and becomes real the longer she stays in the past. She develops memories of her steamboat trip, initially a story she thought she made up, and when she has returned to the present she finds historical documents about herself and Antigua/Omi Saide. The ways in which the gods and spirits have interfered and influenced her are the backdrop of the narrative: the magic which makes all of her travels possible is from them, and the danger of which is obvious when she nearly dies upon her initial transport is also due them. (Those figures argue over her, and the danger of having transported her, as she lies feverish and close to death.) This, too, changes her idea of her identity—she becomes part of a narrative of belief and magic that spans centuries and provides a tie to her own self and her new families in the past.

The intertextual narratives of past and present have wound themselves into two separate but interlocking realities for Sophie, and the novel leaves her at the cusp of trying to assimilate and understand them. She has been changed dramatically by her experience—might I add that I love the fact that, while she is gone for maybe a half-hour from her world, when she returns her body has still aged over the time she spent in the past?—and has to come to terms with the ways in which she will grow into those changes. She is stronger, but for all she has gained she has also lost: her family of the past is gone and dust, and her family in the present no longer feels quite like family but like the strangers whom once owned her, with their racism and their casual bigotry. Even her previously strong connection to Aunt Enid has faltered; while Enid by necessity believes her about her travels and helps her to cover it up as best she can, there is still the barrier of perception and understanding between them. Enid reacts uncomfortably to the escaped-slave notice which says that Sophie can pass for white, and to Sophie’s insistence on the humanity and dignity of the people of color they encounter; even she is not safe, the way she was before the life-altering journey. The novel ends on her decision to go to New York to meet her father’s new wife and to spend time with him, away from her mother and the Fairchild family. Sophie has come back to her time, but who she is now is still up to her to decide, and what identities she will retain are up to her—but there’s no mistaking that her worldview has changed drastically and permanently, for the better. It’s a hopeful ending, but also bittersweet, and leaves open the ways into the future for Sophie to walk as she walked out of the hedge maze—in Antigua’s footsteps.

The Freedom Maze is, frankly, a stunning book on every level. The eighteen years that went into drafting it were obviously time well spent; the precision and complexity of the book speaks volumes to readers young and old. It provides both entertainment and illumination, the two things which art should aim for, and does it beautifully. The engagements with gender—especially the ideas of what it is to be a woman in the 1960s, the pressure Sophie’s mother puts on her to wear bras, which she doesn’t need, and hose, and high heels in a displaced desire for “lady-likeness” while she herself has to become a professional and a provider—and the engagements with what it means to be family and to make a family are particularly moving from a feminist standpoint, and the equal or more intense attention to class and race form a unified whole which examines oppression, bigotry, survival and what it means to be. The afterword speaks clearly to the desire to write a book which is as true as it can be, acknowledging the potential pitfalls of a narrative written by a white woman about black experience and the research, consultation, and effort to write the novel as best as it could be written. That research and effort come to real fruition in the emotional freight of the story.

I regret that it is impossible for this review to explore as thoroughly and as deeply as I would like to the ways in which this book works, but I have at least tried to scratch the surface; there’s just too much to talk about. Sherman has written a novel which pleases me on every level I wish to be pleased as a reader and an activist, challenging perceptions and received wisdom on race and history to draw clear pictures and tell true stories. As a coming-of-age story it is a triumph; as an exploration of racial inequality and the sharp edge of American history it is moving and enlightening; as a deconstruction of Southern myth into reality it is vibrant. I highly recommend The Freedom Maze, not only for its beauty, but because it is one of the most engaging and challenging novels of the year, filled with magic and truth.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.