In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

This book is the final volume of a trilogy that stands as Leigh Brackett’s most ambitious work of planetary romance. With scientific advances making the planets of our own solar system obsolete as settings for this type of adventure, she invented the planet of Skaith from scratch—and what a wonderful setting it was for a tale with epic scope, thrilling adventure, and even a timely moral for the readers.

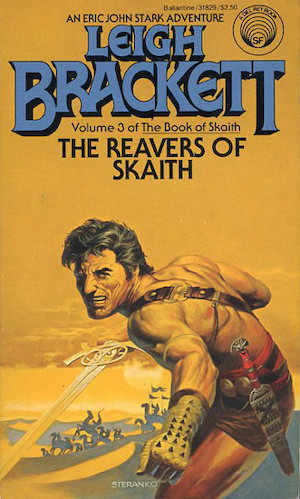

This paperback, like the previous two of the trilogy, has a cover painting by Jim Steranko. The first was among my favorite depictions of Stark, dark, brooding and powerful. The second was not as powerful, although it did accurately capture the reddish glow of Skaith’s ginger star. This final one is more generic, and features Stark alone against a rather basic yellow background. I remember a story about how no one used yellow on covers until someone (I think it was Michael Whelan) did a cover in yellow on a book that became a bestseller, and it became all the rage. I’m not sure if that was the impetus for this cover, but it may well be.

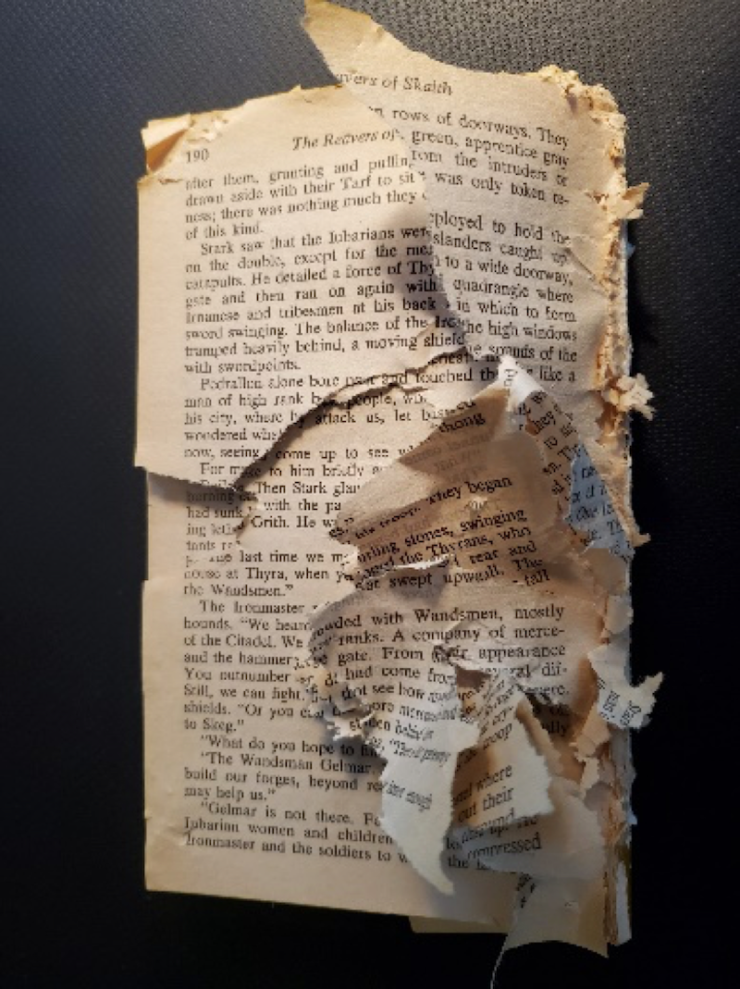

This review was not without its challenges. When I had nearly finished it, I heard a noise from the other room, and discovered our one-year-old dog, Stella, chewing on this:

Yes, those are (or were) the final pages of The Reavers of Skaith. Stella has never done anything like this before, and I hope she will never do anything like it again (this book unfortunately, while available in electronic format, has become rare in paper form). While I had finished reading the book, I did not have the final pages available to check as I finished the review. So, when my recap ends a few chapters before the end of the book, it’s not just because I wanted to avoid spoilers…

About the Author

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) was a noted science fiction writer and screenwriter, perhaps best-known today for one of her last works, the first draft of the script for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. I’ve reviewed Brackett’s work before—the omnibus edition Eric John Stark: Outlaw of Mars, the novel The Sword of Rhiannon, the novelette “Lorelei of the Red Mist” in the collection, Three Times Infinity, the short story “Citadel of Lost Ships” in the collection, Swords Against Tomorrow, the collection The Best of Leigh Brackett, and the first two books of the Skaith Trilogy, The Ginger Star and The Hounds of Skaith. In each of those reviews, you will find more information on Leigh Brackett and her career, and in the last two, you will find information on the planet Skaith, and the trilogy’s story so far.

Like many authors whose careers started in the early 20th century, you can find a number of Brackett’s stories and novels on Project Gutenberg.

The Problematic History of the “Noble Savage”

Google’s Oxford Languages dictionary defines the term “noble savage” as: “a representative of primitive humankind as idealized in romantic literature, symbolizing the innate goodness of humanity when free from the corrupting influence of civilization.” For readers who haven’t encountered the phrase before, while the term might appear complementary, it is based at its core on negative stereotypes.

Eric John Stark’s story is shaped in a way that makes him an exemplar of this concept. His parents were explorers in the habitable twilight zone between the light and dark sides of the non-rotating Mercury (an element of the story that has long since become fantasy in light of scientific evidence). When they were killed, the orphaned child was adopted by a tribe of ape-like creatures who named him N’Chaka, or “man without a tribe.” Thus, Stark is like a number of other literary figures raised by wild creatures, including Romulus and Remus, Mowgli, and Tarzan. A murderous group of human miners exterminated the creatures and put N’Chaka in a cage, where he was found by government official Simon Ashton. Ashton adopted him and re-introduced the child to human civilization. But while Stark gained a veneer of civilized behavior, at his core he is a fierce warrior and a ruthless enemy to anyone who threatens him or his friends. He continually takes the side of the needy and the downtrodden, often throwing himself into great personal danger to assist them. Without romanticizing him, Brackett makes Stark an interesting character with many admirable qualities.

Buy the Book

In the Watchful City

The term “noble savage” became common in the 17th and 18th century, as various European powers were attempting to colonize the world. The “savage” part of the phrase is based on the idea that non-Europeans were inferior to the civilized Europeans (and racism played a large part in this philosophy). However, one could argue convincingly that while the Europeans were good at sailing and navigation, had mastered the use of gunpowder in warfare, and espoused a philosophy that justified their pillage, plundering, and subjugation, they were actually not terribly civilized or enlightened at all. The general view of the Europeans towards others could be summed up with Thomas Hobbes’ famous phrase that men’s lives in nature are “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

That negative viewpoint was quite obviously undercut by the fact that there is decency found in pretty much every human culture. And there were some who idealized the cultures that were not “tainted” by civilization. I had always thought the French philosopher Rousseau had coined the phrase “noble savage,” but Wikipedia tells me that while he wrote about humanity’s potential goodness and discussed the differences between various stages of primitive society, the phrase itself came from others. (As a side note, I also found out that Rousseau was not actually from France but was born in Geneva, and thus Swiss—though he did speak and write in French and spent most of his life in France).

The character of the “noble savage,” whose innate decency is a reproof to those who think themselves superior, has become a quite common one in literature, especially in American literature, where many frontier tales have characters of this nature (for example, the work of James Fenimore Cooper, author of Last of the Mohicans). The website TV Tropes has an article on the term, which includes links to a number of other similar literary character types.

The Reavers of Skaith

The previous volume ended on a positive note, with Stark’s adoptive father Simon Ashton loaded onto a spaceship for home and Stark remaining on Skaith to deal with some unfinished business with the Lords Protector and Wandsmen. This volume opens on a darker note, however, with Stark being tortured for information. The treacherous spaceship captain Penkawr-Che, along with some associates, decided that plundering the dying planet would prove more lucrative than hauling passengers and used Ashton as bait to capture Stark. Under duress, Stark has regressed into his savage N’Chaka personality, and does not possess the vocabulary to give the captain the information he wants.

This final volume, like the others, includes a map that shows the route travelled by the characters. In fact, it has three maps (one from each volume of the trilogy), which is useful. And it also has a handy guide to the background, places, and people who have previously appeared in the books, which turns out to cover quite a bit of information. Brackett has used the extra room afforded by the trilogy format to expand this story to epic proportions. And while, in my review of the last book, I said the book felt like a “seat of the pants” kind of narrative with a weak story arc, this final volume changed my opinion. Plots and characters from previous volumes are brought back and woven into what turns out to be a very moving story of not just what happens to Stark and his companions, but the death throes of a rapidly cooling world. There is also a nice moral to the tale, touching on what happens to people who ignore science and cling to the status quo even as it crumbles around them—a moral that is an unfortunately timely one to those of us reading in 2021.

The second chapter of the book reintroduces us to the Lords Protector and Wandsmen, still clinging to their old beliefs and trying to maintain their dictatorial power, but also having increasing trouble feeding the indigent Farers who follow and depend on them. We get a recap of what has happened to Ashton and Stark since the last volume ended, and see them escape from Penkawr-Che in a grueling sequence of adventures. They decide they need to find Pedrallon, a renegade Wandsman who has a radio they can use to call for help.

The viewpoint then shifts to Stark’s companions in the dying city of Irnan, where Stark’s lover, the prophetess Gerrith, tells them they must travel to assist him. So she, the northhounds, the swordsman Halk (who had promised to kill Stark once they defeat their enemies), the winged Fallarin, and a collection of other allies, head south. Stark and Ashton have perilous adventures on the road, but they survive, and see the hoppers of the starships flying to find plunder. We again meet the underground-dwelling Children of Skaith-Our-Mother, who before the story ends must fight off outworlders, only to retreat back into their caverns even though they are doomed if they stay, and Brackett manages to inspire in the reader a bit of pity toward this bloodthirsty tribe.

Stark and Ashton barely survive contact with the seagoing Children of the Sea-Our-Mother as their friends and allies rejoin them in a nick of time, and their quest takes them to the seas. Everywhere they go, they see signs that the planet is growing colder as the ginger star above fades. They find Pedrallon and enlist his aid. Gerrith has a date with her destiny which leaves Stark heartbroken. And everything leads the main characters, both protagonists and antagonists, to the city of Ged Darod, where a final battle will decide the fate of the planet.

The end of the story is bittersweet but satisfying. A number of characters are given curtain calls to bring their various plot threads to conclusion. The scope of this trilogy was larger than any of Brackett’s previous planetary romances, and in the end, she used that larger scope to good effect. This was among the last tales she wrote in this genre, and it was a fitting end to what might be seen as the Golden Era of the planetary romance story. There were apparently more Stark adventures planned, and with the renewed attention Brackett got as one of the writers of the hit movie Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, they probably would have sold very well. But her untimely death at age 63 prevented what could have been the biggest success of her career.

Final Thoughts

I am not quite finished with my series of reviews on Leigh Brackett. I still have her most critically acclaimed book to look at, The Long Tomorrow. And I have a few more short story collections, which I will probably look at in a single final column.

The Skaith trilogy is certainly worth reading for fans of the planetary romance genre. The planet is rich in detail, and full of people, places, and settings that are perfect for adventures. And the dying planet is a powerful character in its own right, one that gives weight to what might otherwise been a relatively simple story. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this final volume of the trilogy, and the previous books as well—and also your thoughts on how the concept of the “noble savage” is exemplified by Eric John Stark.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.