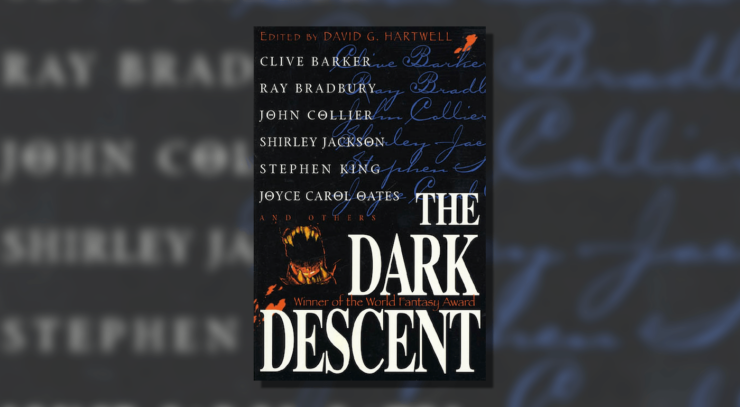

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Robert Aickman is an author whose acquaintance we’ve made before in this feature. With his “strange stories”—works that often satirized society by exaggerating societal elements and performativity to horrific proportions and grim humor—he carved a path through horror fiction that celebrated the unnerving, absurd, and inexplicable. “The Swords” turns that acerbic wit and talent for the absurd towards masculine sexuality, using its unnamed narrator to explore sexual trauma, masculine performance, societal roles, and the horrifying disposability of both women and men caught within that web. “The Swords” turns the expected into a forced performance bordering on psychosexual existential horror, and in the process demonstrates the twisted way gender roles can trap a person even when they resist.

After the death of his father, a young man is taken under his uncle’s wing as a traveling salesman. Moving from one place to the next, he finds himself in a small English factory town called Wolverhampton, where the only attraction is an incredibly sketchy fairground. Desperate for some amusement (and feeling pressured after making eye contact with the barker), he stumbles into the tent for an attraction called “The Swords,” an odd display focused on volunteers from the audience stabbing a young woman and kissing her for the price of two pounds. What the unnamed narrator doesn’t realize is that witnessing this bizarre performance will throw him into a bizarre and inescapable performance of his own, one that ends in a seedy business transaction, a traumatic experience, and the maiming of a young woman.

The first thing we should discuss is the fact that the metaphor is very blunt. “The Swords” is a story about a young man’s traumatic first experiences with sexuality. It’s not subtle. The idea of viewing a softcore show where “Madonna” (a name that evokes both the Virgin Mary and the “Madonna-whore complex” that sees women as either temptresses or saintly mother figures) is stabbed with phallic objects and kissed all for the price of two quid a head—seemingly transforming from a pallid and corpse-like object as the show proceeds, slowly appearing more and more lifelike with each stab and kiss; the way the narrator is manipulated into spending his money on a “private show” by Madonna’s manager; even the way everyone treats the howling and sobbing Madonna as disposable after she leaves the narrator…all correspond directly to what’s thought of as a young man’s “rite of passage.” In the short time the narrator spends in Wolverhampton, he gets his first taste of an explicitly sexual show, develops a case of obsessive love for Madonna, has an ultimately confusing and deeply disturbing first sexual experience with a sex worker, and is promptly left confused and horrified, with more questions than answers.

It’s a distressingly common experience, as is the obvious manipulation the narrator undergoes to get him into bed with Madonna. From the moment he stumbles into (and then out of) the tent where the titular “Swords” performance takes place, he’s on the hook. He’s led through a series of events as if he’s simply “supposed” to follow along. It’s all very scripted, with the disoriented protagonist led through encountering Madonna and her manager, getting the money for the “private show” with Madonna (with an old man cheering him on while giving him a fiver to sleep with her), and finally getting into bed with her, feeling totally out of control and unable to say no or stop the experience. He doesn’t seem particularly eager to climb into bed with Madonna, and the experience borders on body horror even before she goes catatonic and corpse-like in his bed and he somehow accidentally yanks her hand off her arm. It’s something he goes along with because it’s what’s expected, and something he didn’t understand he didn’t have to consent to—not something he wants. In the end, both he and Madonna are left traumatized by it.

The scripting and manipulation beneath the sexual trauma are an equally interesting part of Aickman’s story. The aspect of performance to “The Swords”—whereby the narrator is forced into his role in the performance as “boy becoming a man via sexual activity”—speaks to a greater truth about masculinity often overlooked in discussions of masculine gender roles. While the sexual coercion is clear and something rarely mentioned in discussions of masculine sexuality—the idea that “a man just wouldn’t say no” is ingrained in our culture even as more time is spent examining and dismantling other harmful aspects of masculinity—it’s a symptom of a larger issue, that being the fact that masculinity is deeply rooted in performance. Masculinity is frequently an adoption of a role either guided by toxic stereotypes or in reaction against those same toxic stereotypes. The rules of patriarchal privilege and oppressive societal norms dictate that refusing this role will result in existence devoid of agency or purpose. Thus, you are forced to perform.

For the entire story, Aickman’s characters exemplify this. The narrator especially has no agency of his own throughout “The Swords.” His weird uncle gives him a job as a traveling salesman and picks out the places he stays in each town. He’s saddled with Bantock, a dirty old man, for his partner and inundated with people asking about his sex life. He stumbles across the tent for “The Swords” and enters the show out of politeness rather than seeking it out. Two people whose only identities are “manager” and “performer” go out of their way to tell him how special he is in order to lead him deeper into the “show” until he agrees to a private performance. Even the kindly older gentleman who gives the narrator half the private show fee appears to be reading for the part of “kindly wiser older gentleman.” So trapped is everyone in this absurd performance that when things do go wrong, they continue to play their parts, with Madonna’s manager accepting payment with a wink and a smile as Madonna’s unholy inhuman howls echo upward from below. Madonna’s role in the performance is as a disposable object, the narrator is now a customer, the manager is a businessman, and the show must go on. The fact that Aickman ends on a note of deep existential horror as the narrator says “Despite what he said, I never saw him again” only drives home how unnerving all of this is.

Absurdist horror seeks out the mundane aspects of life normally taken for granted, the unanswered or unquestioned ideas underpinning our existence, and exaggerates them to the point that we’re forced to confront the horrifying truth in our lives. “The Swords” does this expertly, painting a young man’s sexual trauma, the objectification of women, and the pageantry of masculine sexuality in such a garish and horrifying light that it’s impossible to ignore the numerous problems with it. Aickman’s portrait of a young man trapped in an existential hell of masculine expectation and trauma feels miserable and deeply unnerving, and it should. After all, the worst fates in horror are existential and never-ending. And the show must (and will) go on.

And now to turn it over to you. Do you think “The Swords” was true to the performative nature of masculinity, and in its depictions of sexual trauma? Is there anything Aickman could have explored in greater detail? And why is it that Hartwell keeps doubling (or even tripling) up on certain authors’ works in this anthology?

Please join us next week for “The Roaches” with elder horror/SF statesman (and game designer) Thomas M. Disch.