People have always had sex. Even in the Victorian era, a time synonymous these days with prudery and abstinence, sexual acts were committed.

In one of the period’s most infamous cases, popular author Oscar Wilde was tried and jailed for the “gross indecency” of making love with other men. Yet Wilde wasn’t alone in his support of “Uranian” (same-sex) relationships. Poet Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover and originator of the phrase “the love that dare not speak its name” (echoed in this post’s title), was also a proponent of the well-known Uranian movement. Since steampunk so often draws on Victoriana, we should find Uranian interests represented in a fair number of steampunk stories, right? Plus, the overtness of sexual markers such as corsets in steampunk, and the tendency of the genre’s authors to imagine modern attitudes into their versions of the past, should make queer steampunk common enough that multiple examples are easy to find. Right? Right?

Alas, other than slash fiction, there’s no long, strong tradition of steampunk stories that ignore heteronormative restrictions. Fan-generated steampunk slash riffs off of speculation about the homoerotic content of films such as 2009’s “Sherlock Holmes” and 1999’s lamentable “Wild Wild West.” And why shouldn’t it so riff? Steampunk is about choosing your own adventures and making your own reality.

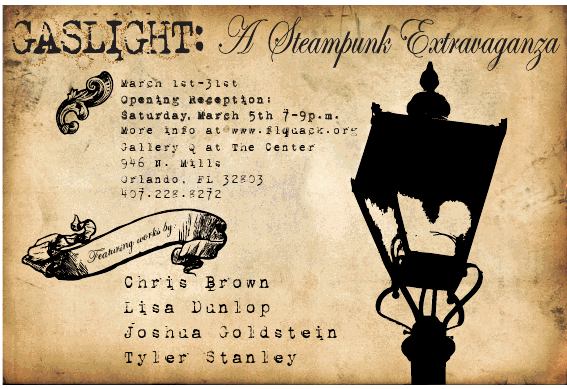

Non-literary varieties of steampunk have been associated with some fine gender bending. The Florida Queer Art Collective, for instance, put together a March 2011 show called Gaslight: A Steampunk Extravaganza, complete with costume door prizes. The online discussion group Steampunk Empire recently compared notes on how to subvert gender dress codes via steampunk cosplay.

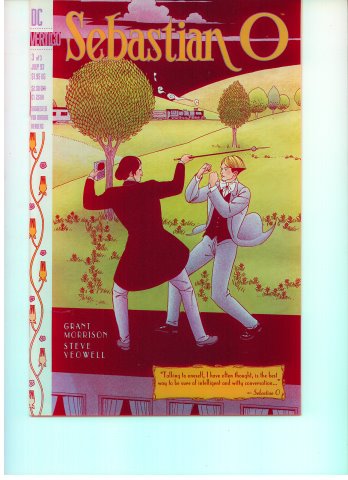

Comics creators Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell produced the earliest example I could find of professional queer steampunk literature. Their Sebastian O series stars a thinly-disguised Oscar Wilde battling the evil mastermind of a computer-generated Queen Victoria, Lord Theo Lavender.

Lavender claims he controls the virtual reality in which he and the Wilde analog live. After Sebastian escapes from Bedlam, a mental hospital notorious for ill-treating its inmates, his investigative path crosses that of a George Eliot/George Sand mash-up (a pipe-smoking woman novelist in male drag) and an ostensibly reformed ecclesiastic pederast. Our hero is not a nice man: he detests the poor and mocks his enemies. But he’s undoubtedly better dressed and wittier than his opponents, and unashamed of his Uranian “crimes.” The comic’s three volumes were originally published in 1993, which makes Sebastian O a contemporary of Gibson and Sterling’s The Difference Engine and places it solidly in steampunk’s first wave. It was reissued as a single volume in 2004.

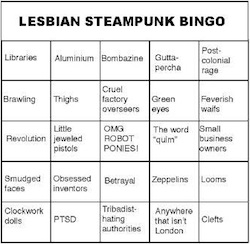

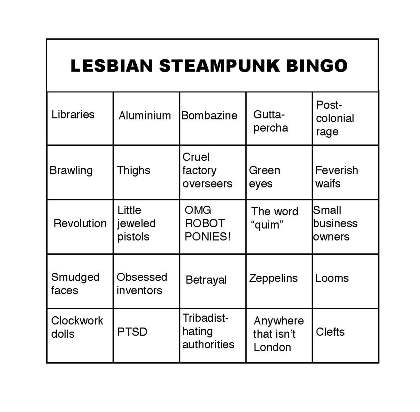

In more recent years, small presses have published steampunk novels with queer romantic elements, such as A Certain Pressure in the Pipes by Clancy Nacht and The Inventor’s Companion by Ariel Tachna. The independent press Torquere published Steam-Powered: Lesbian Steampunk Stories in January 2011. In late October of the same year, they’ll release the sequel anthology Steam-Powered 2: More Lesbian Steampunk Stories (including an excerpt from my novel-in-progress, Everfair). With tongue firmly in cheek, Liz Henry of bookmaniac.net included this Lesbian Steampunk Bingo Card in her review of the first book.

Further queer steampunkery looms on the near horizon. In preparation for this post, I questioned two new authors about their contributions to the subgenre. Jude-Marie Green discussed her short story “A Glorious Madness” appearing in Issue #2 of Unfettered Fantastique. Jei D. Marcade discussed “The Anarchist’s Wife,” her unpublished Clarion West Writers Workshop submission story. Both feature bisexual protagonists.

Interview:

Nisi Shawl: What moved you to include queerness in your recent steampunk story?

Jei D. Marcade: The realization that despite my protagonist’s attempts to manufacture a rigid structure for her life, her natural inclination is to chafe at limitations of any kind, including those placed on her sexuality.

Jude-Marie Green: I am straight and attracted to men, not women. Except now and again I’ve been blindsided, though I didn’t feel the desire to pursue those attractions. I do love the rush of a strong, stimulated libido. But a relationship, especially a road relationship such as the one between Donna Quick and Jane Smith, goes way beyond libido. There’s teamwork, respect, and compassion. These are all parts of the personal interactions I tried to explore in this story.

Shawl: Do you anticipate doing more along these lines?

Marcade: Absolutely. Before I wrote “The Anarchist’s Wife,” my brain birthed a long and winding clockpunk plot-thing that I’m currently trying to wrestle into either a novel or short story serial, and which features characters who might, if prodded, rate themselves a “one” on the Kinsey scale. You’ll probably see me whining about it come NaNoWriMo.

Green: Yes, I’m writing a sequel.

Shawl: Is there a resonance or relationship between steampunk and queerness?

Marcade: I suppose there could be a relationship, if queerness were equated with the subversive element inherent in the portmanteau “steampunk.” I was blessed to have grown up with queer friends in fairly liberal environments, so queerness sort of wove itself into the fabric of my reality and doesn’t retain any especially subversive connotations. My super-secret-evil-plan is to see the world shed previously held criteria for certain strains of “normative behavior,” which at times I manifest by stubbornly ignoring that they exist. But I can see how queerness might be an attractive platform from which one could write in what has been a pretty starkly heteronormative body of literature, at least on the surface.

Green: Honestly, I don’t know if there’s a resonance or relationship there. Queer is part of the human condition, right? So you’d think it would be all through the literature. All literature. But it does seem strangely absent. We might as well write what’s real: attraction happens. And the human race, as a whole, isn’t vanilla.

Nisi Shawl won the James Tiptree, Jr. Award for her 2008 story collection Filter House, and she was WisCon 35’s Guest of Honor. She’s still hard at work on her Belgian Congo steampunk novel-in-progress, despite the temptations of social media and the necessity of earning the rent on her apartment. She thanks Professor Thomas Foster of the University of Washington for loaning her his cherry copies of the Sebastian O comics.