Once in a while, I’ll spend a good thirty seconds staring into the mirror, briefly entranced by it. Not by my reflection, mind you, but by the mirror itself. I’m fascinated by its polished sheen and its ability to perfectly reflect what stands before it. What a simple, pleasing, functional item, able to perform its duty without mechanics or electricity. A mirror isn’t concerned with its role in the world. It sits, stands, hangs wherever you’ve put it and performs its function, ever diligent.

Well, at least in our world.

Sprinkle magic onto a reflective glass surface, and you can explore the darker side of seeing yourself in a different light, sometimes warping reality, sometimes revealing hidden truths. Mirrors in fantasy beckon characters into sinister worlds. They imprison malevolent forces. They show us what we aren’t meant to see.

Let’s explore some of the ways that fantasy twists our fascination with mirrors and reflections to shape different kinds of stories and take characters to strange, sometimes sinister places.

Portals to Other Worlds

A rippling of the glass. A creepy glance from your own reflection. A “come-hither” motion from your not-quite self beckoning you to the other side…

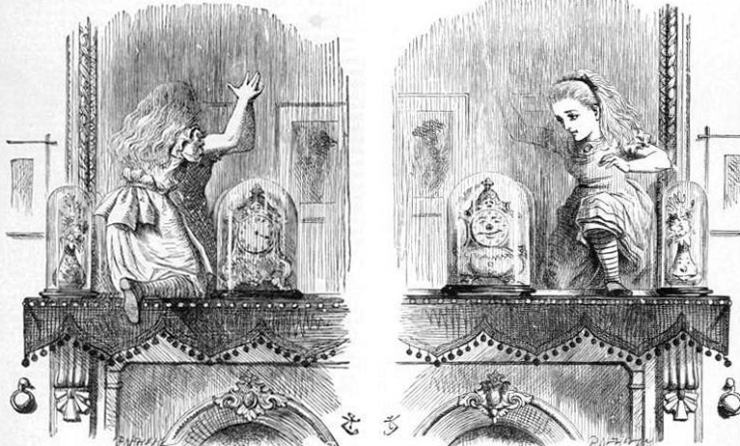

Mirrors as portals to other worlds are a fantasy-horror staple—what lies beyond the shining surface tends to twist and warp our version of reality into something far less benign. But sometimes the other side of the glass is more whimsical or surreal. In Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, our plucky heroine climbs into a mirror to reach the Looking-Glass House reflected in it. The world she encounters is topsy-turvy—everything is reversed, including essential functions of everyday life. Running keeps you stationary, for example. Other changes abound, including anthropomorphic chess pieces and classic storytime characters that are alive and well in this version of reality.

Through the Looking-Glass provides fertile ground for Lewis Carroll’s trademark wackiness and absurdity. The story plays upon our expectations as Alice attempts to adapt to a world at odds with her reality, a reflection of the life she knows.

Many other stories take this approach; Locke & Key springs to mind, though it also has lore involving magical keys used to access the mirror world.

“Mirrors as portals” is a relatively straightforward device: The mirror bridges one world and another, but those actual worlds do the heavy lifting in the narrative, and the success of the story largely depends on how an author imagines and conveys the oppositeness and off-putting differences of the other side of the looking-glass. The mirrors in these stories essentially function as magical doors. They symbolize the “other side,” whatever that may be in the mirror’s story.

A Vessel for Souls

Of the three fantasy-mirror functions I’ll explore, this one’s my favorite. Instead of acting as a border between worlds, some stories imagine that mirrors can hold souls—or even tiny universes—trapping (or preserving, as we’ll soon find) beings within their mysterious reflective walls.

Netflix’s The Dragon Prince, co-created by Avatar: The Last Airbender writer Aaron Ehasz, has so far followed a three-season arc starting in 2018 and concluding in November of 2019. Among many compelling storylines, one thread involves Aaravos, a Startouch Elf trapped in a magical mirror.

I’ll avoid heavy spoilers here, mainly because The Dragon Prince returns from hiatus with season 4 this November and the season’s subtitle is “Mysteries of Aaravos.” But some mild spoilers are necessary, so read this section at your own risk.

Though, come to think of it, it’s hard to spoil much. Aaravos remains a mystery (hence the subtitle of the upcoming season, I guess). Viren, the former advisor to the king, discovers the mirror that holds Aaravos and begins working with the trapped elf to advance his own traitorous ends. Throughout the series, we learn that Aaravos was trapped there by the Archdragons of Xadia. Why, though? I’m sure we’ll get some insights in the coming seasons, but we can assume he was up to some verifiably sinister shit. You must’ve done some reprehensible stuff for the most powerful magical beings in the world to lock you away permanently.

And it makes for a fascinating storyline, because at the end of the day, trapping an insanely powerful and dangerous being inside a mirror is just cool. Stories that take this approach lend power to mirrors that wouldn’t work in the portal stories I describe above. A world hidden behind a mirror is borderline inaccessible. If the Archdragons and Elves could lock Aaravos away in a more secure prison, would they not do it? It’s an intriguing and somewhat horrifying way to imagine the other side of our reflected world…Aaravos isn’t locked away in some far-off land. He’s trapped, but he is there in front of us, in front of Viren. He is exiled, alienated to an almost unimaginable degree, but can still function as a character without existing on our side of reality.

Okay, The Dragon Prince spoilers end here. Now, we shift into Ranking of Kings spoilers. And hoo boy, you should watch this one. It’s one of the best newer animes out there.

Ranking of Kings bursts at the seams with glorious characters. Bojji, the protagonist, is the star of the show. He’s adorable and endlessly relatable. But Lady Miranjo, a woman trapped within a hexagonal mirror, will be our focus here. Here’s your spoiler warning, for those who need one!

Miranjo participated in two attempted coups of the Bosse Kingdom (ruled by the family Bojji was born into). During the first, she was slain, but she struck a deal with a demon to preserve her mind in a mirror. Trapped in the mirror for a decade, Lady Miranjo began plotting and eventually kicked plans into motion to restore her body and free her from the mirror. Forced to execute her machinations from within the mirror, Miranjo begins by manipulating the dour Prince Daida—shortly after his coronation—into doing her bidding.

Whereas Aaravos of The Dragon Prince was thrust into his prison—which, I should note, is furnished with various supplies and comforts—Lady Miranjo’s soul was transferred into the mirror of her own accord with help from a powerful entity. The prison, in a way, is of her own making. It’s a vast emptiness in which a soul can survive, but a body cannot.

The fundamental differences between Lady Miranjo’s and Aaravos’ imprisonments speak to the limitless potential of mirrors as vessels, prisons, and places of exile. For Aaravos, the mirror is a window to the world from which he has been banished. For Miranjo, the mirror becomes her reality, a distant reflection of the world other characters see, touch, and experience as real. Still, both characters are unified by a common goal: to escape and win back the lives that have been taken from them.

Showing Us the Unseen

Now we come to our third main use of mirrors in fantasy: showing us the unseen. This conceit rears its head in any number of fantasy tales, though the form varies.

Consider the Potterverse’s Mirror of Erised and its ability to show the onlooker what their heart most truly and deeply desires. It’s not a gift to be taken lightly: It’s easy to get lost in the sauce, so to speak, and forget to live (I wish that was a verbatim Dumbledore quote). Our desires can take shape in our minds and become driving forces to shape our goals and worldview, but seeing them made semi-real in the reflection on the glass can be a mind-mucking thing. No wonder the mirror symbolizes Voldemort’s myopic and intense focus on a singular goal—to live forever. The Mirror of Erised shows us the dark side of our dreams and the danger of pursuing them at the cost of enjoying the everyday life required to achieve them.

The Brothers Grimm and even the optimistic, dreamy-sheened Disney adaptations of their darker tales can show us the dangers of seeing what’s meant to remain out of sight.

Snow White’s Evil Queen constantly asks her Magic Mirror (which is on the wall, in case you forgot): who is the fairest of them all? The queen delights in hearing that she is the fairest…until she isn’t. Snow White starts popping up to replace the mirror’s reliable stock answer, which had previously assuaged the queen’s narcissism.

The Magic Mirror—and I do mean the magic mirror, as it’s probably the most famous one to grace pages or screens—is kind of like the fairytale version of Instagram, serving only to detract from one’s sense of self-worth by showing the highlight reel of fairer, happier counterparts maintaining impossible levels of perfection.

Also—and this is not important in the scope of this piece, but I’ve gotta ask—is the Mirror sentient? Is there a guy trapped in there? Is this some sick, twisted combination of soul-trapping and whoever’s in there is forced to answer the queen’s questions ad nauseam? We may never know.

Elsewhere in the Disney realm, Beauty and the Beast’s enchanted mirror approaches the problem from a different angle. It won’t answer your questions. It won’t purport to be an all-knowing entity, dictating truths from its comfy wall perch. No, the Beast’s (and later Belle’s) mirror shows the onlooker anyone they wish to see but only as they currently exist, providing a window to somewhere else in the world at that precise moment.

Beauty and the Beast first makes a case for the helpful, positive use of such a magical object; after the mirror shows Belle that her father is lost in the woods and about to be attacked by wolves, she is able to rush to his aid. But the potential darker side of using the enchanted looking glass comes through later. The Beast listens in on Belle’s conversation with the wardrobe, where he hears that she has no interest in being with him. Later, Belle reveals the Beast’s existence to an angry mob using the mirror (in an attempt to reason with them and prove her father’s sanity), but the villagers, melodically proclaiming “we don’t like what we don’t understand; in fact, it scares us,” march to the castle to kill the Beast.

In this case, the mirror is very much a double-edged sword; sometimes it can inspire heroism, other times the visions it shows cause hurt feelings and misunderstandings, and sometimes the truths it reflects can be twisted or used to stoke preexisting fears and prejudices. It’s a reminder that context matters, that it’s easy to misinterpret or misuse information. Perhaps—and hear me out on this—we aren’t meant to have an all-access pass to intimate moments or conversations between friends (or celebrities and other strangers, for that matter). Also, maybe it’s not helpful or healthy to constantly absorb images and videos that only serve to hammer home the opinions and versions of the truth we already espouse without allowing room for other interpretations or points of view. Belle’s mirror may not have set out to be a symbol for privacy and introspection, but it became one anyway.

Reflections

I’ll likely look in the mirror later and reflect on this piece: Was it too rambly? Did I capture my ideas in the way I wanted? Obviously the examples mentioned above weren’t meant to be an exhaustive survey, but have I missed any particularly glaring instances of memorable fantasy mirrors?

I can’t stop myself from such lines of thought. But you can at least help me fill in that last blank. Let me know what you think about fantasy mirrors, and please share your own favorite examples and any related stories I should check out! Thanks, as always, for reading!

Cole Rush writes words. A lot of them. For the most part, you can find those words at The Quill To Live or on Twitter @ColeRush1. He voraciously reads epic fantasy and science-fiction, seeking out stories of gargantuan proportions and devouring them with a bookwormish fervor. His favorite books are: The Divine Cities Series by Robert Jackson Bennett, The Long Way To A Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers, and The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune.

John Bellair’s mouthy mirror from The Face in the Frost , which is just as likely to offer a view of a kingdom ancient to the medieval-type setting but deliver video footage of a football game It’s “given to tuneless humming and crabby remarks”.

“Ov-er-head the moon is SCREEEEEAMING, white as turnips on the Rhine” . . .

I thought first in terms of your third category, what is seen in the mirror: your true self, your heart’s desire, and the dead. I’m not sure where The Neverending Story instance fits, since it isn’t entirely clear what it means.

The mirrors of the Mordant’s Need duology almost deserve a category of their own.

There could be a fourth category, where the mirror provides prophecies of the future. One example is in Novik’s A Deadly Education, El is forced to make mirror that will provide dark prophecies as a required shop project in order to finish her academic obligations and move onto her senior year. El, of course, has no interest in the evil prophecies the mirror will give her once created (and she covers it up so she doesn’t have to listen). Query if there are other examples out there about prophetic mirrors.

Mirrors are way too cool. They just have that mystic aura, that chance of endless possibilities of something just beyond our reach. It is not for nothing mirrors used to be covered up if there was a death in the house, or that people who claim to communicate with the other side so often use them or talk about their significance. Just as there is a reason smoke and mirrors is a thing.

Regarding these three categories, excellent examples in the article (and I am sure also in the comments, though I am unfamiliar with these). Off the top of my head, I remembered these.

When I was still a pre-teen, I really liked an Australian-New Zealand YA series “Mirror, Mirror”. The mirror served as a portal there as well, but instead of two worlds, it connected two different eras – when placed exactly in the same spot, it transferred you from 1995 to 1919 and vice versa. New friends and adventures naturally followed. I spent over a decade wishing (and looking) for myself a mirror that would look just as this one in the series, even knowing full well that it would be a simple interior object, it just looked so cool and impressive, old and beautiful as it was.

Regarding souls trapped in a mirror, an excellent example comes in the series “Supernatural” which found ways to use and introduce all kinds of legends and folklore throughout its 15-year-long run. It was already in the fifth episode of the very first season when the brothers had their hands full with Bloody Mary, the spirit of a murdered woman now trapped in the mirrors.

As for mirror showing what was, is, or might yet be, maybe not as famous as the Evil Queen’s mirror, but close on its heels, I think, is the Mirror of Galadriel in Lothlórien.

Also, the Mirror of Erised was mentioned, but Harry also had the set of two-ways mirrors Sirius gave to him to talk to each other.

There are wonderfully many mirrors in fantasy. I, for one, cannot get enough of them.

RobMRobM@3: I would call that a subtype of category 3, “showing the unseen”. Tolkien’s Mirror of Galadriel falls into this category also, though Galadriel herself warns that the mirror’s future visions may be things that happen only if you turn aside from your path to prevent them, and that the mirror is unreliable as a guide to action. (Prompting my wife to ask, “Well, what good is it then?”)

@1. WMc

Don’t forget the “bagpipes playing Gregorian chants”

. One of my favorite books, I was coming here to mention the mouthy magic mirror from The Face in the Frost and you beat me to it

. One of my favorite books, I was coming here to mention the mouthy magic mirror from The Face in the Frost and you beat me to it

As a matter of principle, this is not correct; you must have seriously pissed off the most powerful magical beings in the world, but that by itself says nothing about which side of that conflict is more reprehensible. Sometimes the mirror-prison could be an unjust fate.

Although in Aaravos’s case it seems likely that there’s plenty of reprehensible on both sides. I won’t get into the details because they would involve spoilers for the seasons that are already out, which some people might want to check out in the next few weeks before the new one drops.

Also, the comment that mentions a series called “Mirror, Mirror” reminded me of the Original Trek episode of the same name, which involves no literal mirrors but is about a parallel universe (aka mirror universe, a reference to Through the Looking-Glass).

One low-tech version of a mirror is a pool of still water, which could also serve in any of these roles (the Wood between the Worlds in the Narnia series, for example).

In the modern era there’s another object known for showing images: a TV (or computer monitor). They too can serve any of the same mythological functions (and in some situations a TV is practically a defictionalization of the scrying-glass).

There’s also the chapter in C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in which Lucy peruses the magician’s book, which functions very much like a magic mirror. (I believe in the movie it is a magic mirror.) It, too, provides the onlooker forbidden knowledge — a spell for beauty and what would happen if uttered (handled differently in the novel and film, though equally disastrous) and a spell to eavesdrop on one’s friends (which ruins Lucy’s opinion of one of her own friends when the latter speaks dismissively of her). There are also “good” spells (a wonderful story, immediately forgotten, and one to make the invisible visible, which is what she was supposed to be looking for to begin with). Also, I note that the Mirror of Galadriel has been mentioned, but what about the Palantirs, which serve as direct communication devices from stone to stone, but also allow you to see scenes of your own choosing — or be forced to see scenes of another’s, if that other is of stronger will. Also instances of magic mirrors — in fact, one could argue all such “cystal balls” are.

In one of the Diana Tregarde books she discovers that a dark laptop screen can be used as a scrying mirror.

In the Bubble of Evil in Tear Rand fights his mirror images.

One of my favorite books with a magic mirror is The Serpent’s Shadow by Mercedes Lackey. This mirror is one with an entrapped spirit that shows a view of people or locations as they are in that moment.

Stephen Donaldson’s “The Mirror of Her Dreams” and “A Man Rides Through” are very much in category 1.

Skulni’s mirror in Fairest by Gail Carson Levine inhabits both categories two and three. The mirror is used as a prison, but also twists a person’s reflection toward their idea of beauty– which is how Skulni lures his victims.

In the regretted Roger Zelazny’s Second Chronicles of Amber, mirrors play major roles: they are windows into other places, but also doors one can step through if one knows how, giving different impressions of reality. They also interact with the world of dreams which, in the Amber/Chaos multiverse, can be just as real as anywhere else. Their role was further amplified and began to be clarified in his Amber short tales (see Seven Tales in Amber), but he died before integrating them into a coherent whole

“One of Castle Amber’s intriguing anomalies, the Corridor of Mirrors, in addition to seeming longer in one direction than the other, contained countless mirrors. Literally countless. Try counting them, and you never come up with the same total twice. Tapers flicker in high, standing holders, casting infinities of shadows. There are big mirrors, little mirrors, narrow mirrors, squat mirrors, tinted mirrors, distorting mirrors, mirrors with elaborate frames – cast or carved – plain, simply framed mirrors, and mirrors with no frames at all; there are mirrors in multitudes of sharp-angled geometric shapes, amorphous shapes, curved mirrors. I had walked the Corridor of Mirrors on several occasions, sniffing the perfumes of scented candles, sometimes feeling subliminal presences among the images, things which faded at an instant’s sharp regard. I had felt the mixed enchantments of the place but had somehow never roused its sleeping genii. Just as well perhaps. One never knew what to expect in that place; at least that’s what Bleys once told me. He was not certain whether the mirrors propelled one into obscure realms of Shadow, hypnotized one and induced bizarre dream states, cast one into purely symbolic realms decorated with the furniture of the psyche, played malicious or harmless head games with the viewer, none of the above, all of the above, or some of the above.”

In Susanna Clarke’s award winning novel, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrel, mirrors also play a major role, as they allow travel onto the Raven King’s Roads and the world of Faerie.

The mirrors in Phantom of the Opera aren’t *precisely* magic, but they certainly play a pivotal, though background role.