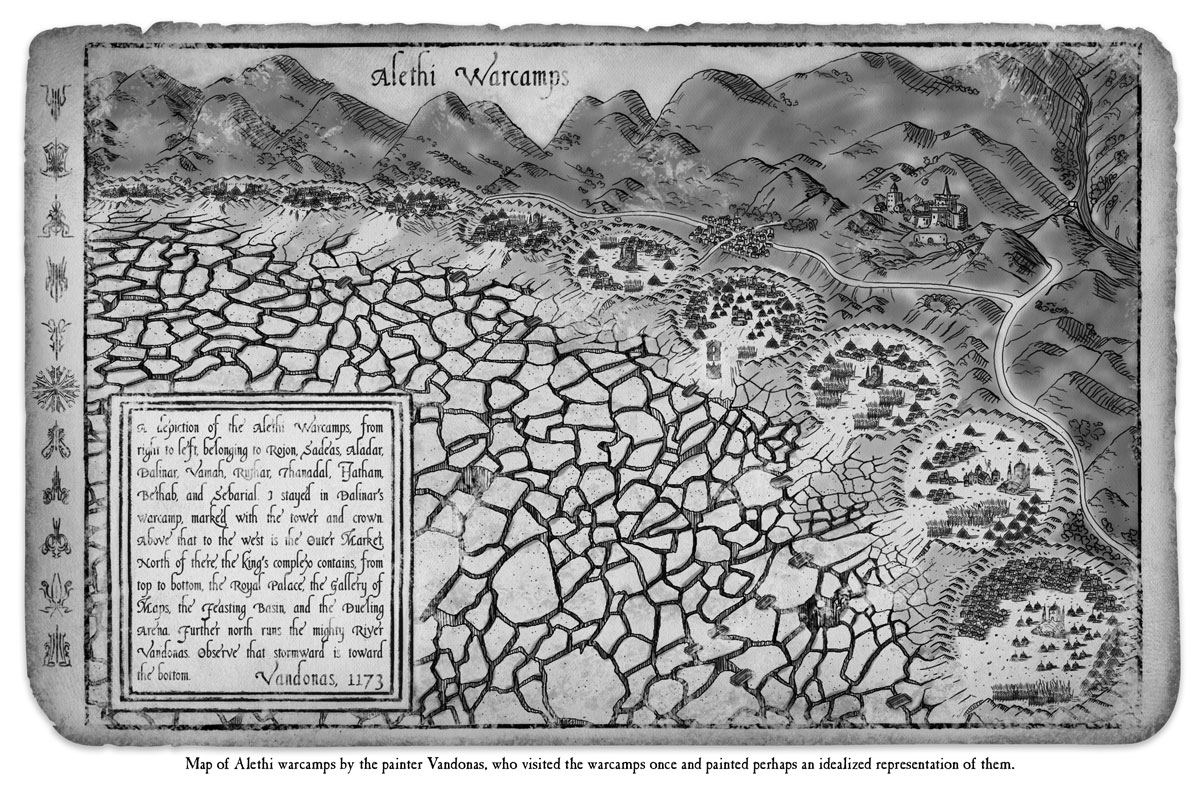

Welcome back to Tor.com’s reread of The Way of Kings. This week I’m covering Chapter 18, another Dalinar and Adolin chapter. The Mystery of the Saddle Strap continues, we learn a bit more about Vorinism, explore the relationships between Dalinar and his sons, and I go on a tirade about dueling, all as a highstorm looms on the horizon. I’ve also got some tentative news about Words of Radiance for all of you, and a full detail map of the Alethi warcamps below the cut.

First, Words of Radiance. After last week’s reread some of you percipient readers noticed that Amazon.com has changed the release date for book 2 in the Stormlight Archive to January 21st. I’ve asked around the Tor offices, and can say that the book is currently scheduled for that date. Feel free to update your calendars, with the understanding that the release date could still change in the future.

Chapter 18: Highprince of War

Setting: The Shattered Plains

Points of View: Adolin and Dalinar

What Happens: A pair of leatherworkers confirm for Adolin that the king’s girth strap was indeed cut, to his great surprise. Before he can hear more, Adolin is interrupted by his most recent girlfriend, Janala, who doesn’t consider their romantic walk to be much of a walk so far. One of the leatherworkers tries to help placate her, and the other reasserts that this was no simple tear, and that Adolin should be more careful. The leatherworkers agree that tears like this can be caused by negligence, and that while it could have been cut intentionally, they can’t think why anyone would do that.

Adolin and Janala return to their walk, but Adolin doesn’t really pay attention to his companion. She asks him if he can get his father to let officers abandon their “dreadfully unfashionable” uniforms once in a while, but he’s not sure. Adolin has begun to understand why his father follows the Codes, but still wishes he wouldn’t enforce them for all his soldiers.

Horns blare through the camp, interrupting them and signaling a chrysalis on the Shattered Plains. Adolin listens for a follow-up that would call them to battle, but knows it isn’t coming. The plateau in question is too close to Sadeas’s warcamp for Dalinar to contest it. Sure enough, there are no more horns. Adolin leads Janala away to check something else out.

Dalinar stands outside Elhokar’s palace, his climb to the elevated structure interrupted by the horns. He watches Sadeas’s army gathering, and decides not to contest the gemheart, continuing to the palace with his scribe. Dalinar mostly trusts his scribe, Teshav, although it’s hard to trust anyone. Some of his officers have been hinting that he should remarry to have a permanent scribe, but he feels that would be a cheap way to repay the wife he doesn’t even remember. Teshav reports on Adolin’s investigations, which has turned up nothing so far. He asks her to look into Highprince Aladar’s talk of a vacation to Alethkar, although he’s not sure whether that would be a problem if true. He’s torn between the potential that Aladar’s visit would bring some stability back to their homeland and the fear that he needs to keep the highprinces where he can watch them.

He also receives reports on the king’s accounts. No one but he and Sadeas have been paying taxes in advance, and three highprinces are well behind. In addition, some are considering moving farmers to the plains to alleviate the price of soulcasting. Dalinar is strongly against this, emphasizing that the histories he has had read to him prove that “the most fragile period in a kingdom’s existence comes during the lifetime of its founder’s heir.”

Keeping the princedoms together as one nation is of primary importance to Dalinar, not just to honor Gavilar’s dream, but also because of the command that haunts his dreams: “The Everstorm comes. The True Desolation. The Night of Sorrows.” He has a missive drafted in the king’s name to decrease the cost of Soulcasting for those who have made their payments on time. Tax loopholes may not be his strong point, but he’ll do what he has to keep the kingdom together. He also commits another battalion to suppressing banditry in the region, raising his peacekeeping forces to a quarter of his total army, and reducing his capacity to fight in the field and win Shards.

Dalinar talks to Renarin about his unwise actions during the chasmfiend hunt, but quickly sees how low his son’s self-esteem is. Renarin can’t fight or train to fight because of his blood sickness, and is incapable of continuing his father’s legacy of excellence in combat. Despite this, he wholeheartedly supports his brother, which Dalinar knows he would have trouble doing himself. He had been bitterly envious of Gavilar during their childhood.

Dalinar tells Renarin that they should start training him in the sword again, and that his blood weakness won’t matter if they win him a Plate and Blade. He is willing to loosen up a little, sometimes, if it will mean his son’s happiness. After all, he knows too well how Renarin feels:

I know what it’s like to be a second son, he thought as they continued walking towards the king’s chambers, overshadowed by an older brother you love yet envy at the same time. Stormfather, but I do.

I still feel that way.

The ardent Kadash warmly greets Adolin as he enters the temple, to Janala’s disparagement. While less smelly than the leatherworkers, this is clearly no more romantic a destination for their walk, despite Adolin’s feeble protestation that Vorinism is full of “eternal love and all that.” She doesn’t buy it and storms out, but at least the ardent agrees with Adolin!

Kadash asks if Adolin’s come to discuss his Calling, dueling, which Adolin hasn’t been making progress on lately. Adolin hasn’t. He wants to discuss his father’s visions instead, out of fear that Dalinar’s going mad, and hopes the visions might conceivably be sent by the Almighty.

Kadash is disturbed by this talk, and says that talking about it might get him in trouble. He lectures Adolin about the Hierocracy and the War of Loss, when the Vorin church tried to conquer the world. Back then, only a few were allowed to know theology. The people followed the priests, not the Heralds or the Almighty, and no layman was in control of his or her own religious path. They also promoted mysticism, claiming to have received visions and prophecies, even though that is heresy. “Voidbinding is a dark and evil thing, and the soul of it was to try to divine the future.” It was later discovered that there had been no true prophecies.

Kadash’s conclusion is that Dalinar’s visions are probably the product of the death and destruction that he’s seen in battle, rather than being sent by the Almighty, but will not go so far as to call Dalinar mad. Adolin reluctantly accepts this, and Kadash tells him to go see to Janala. Adolin does so, but figures that he probably won’t be courting her for very much longer.

Dalinar and Renarin reach the King’s chambers, passing Highprince Ruthar, who is waiting for an audience. They are admitted immediately, annoying Ruthar. Elhokar is staring towards the Shattered Plains, wondering if the Parshendi are watching him. He and Dalinar discuss why the Parshendi killed Gavilar. Dalinar still wonders if it was a cultural misunderstanding, but Elhokar says that the Parshendi don’t even have a culture, and cuts the conversation off.

Dalinar broaches the difficult subject of how long they will continue the war, weathering the backlash that follows. He argues that the war is weakening them, as Elhokar contests that they are winning the war, that this strategy was Dalinar’s in the first place, and that Dalinar has lost his courage entirely.

Finally, Elhokar asks his uncle whether he thinks him a weak king. Dalinar denies it, but Elhokar pushes further.

“You always talk about what I should be doing, and where I am lacking. Tell me truthfully, Uncle. When you look at me, do you wish you saw my father’s face instead?”

“Of course I do,” Dalinar said.

Elhokar’s expression darkened.

Dalinar laid a hand on his nephew’s shoulder. “I’d be a poor brother if I didn’t wish that Gavilar had lived. I failed him—it was the greatest, most terrible failure of my life.” Elhokar turned to him, and Dalinar held his gaze, raising a finger. “But just because I loved your father does not mean that I think you are a failure.”

Elhokar says that Dalinar sounds like Gavilar, towards the end, after he began listening to The Way of Kings. He frames this as a weakness. Dalinar reframes his own argument; instead of retreating, push forward. Unite the armies around a new goal, defeat the Parshendi once and for all, and go home. To do this, he asks Elhokar to name him Highprince of War, an antiquated title for the Highprince who could command the combined armies of all the others. Elhokar ponders this, but thinks that the others would revolt and assassinate him. And when Dalinar promises he’d protect him, Elhokar says that he doesn’t even take the present threat to his life seriously. After further back and forth, their discussion grows heated:

“I am not getting weak.” Yet again, Dalinar forced himself to be calm. “This conversation has gone off the path. The highprinces need a single leader to force them to work together. I vow that if you name me Highprince of War, I will see you protected.”

“As you saw my father protected?”

This shuts Dalinar up immediately. Elhokar apologizes, but asks why Dalinar doesn’t take offense when wounded. Eventually they reach a compromise. If Dalinar can prove that the highprinces are willing to work together under him, then Elhokar will consider naming Dalinar Highprince of War.

Dalinar leaves, pondering who to approach. Renarin interrupts his thoughts in a panic; a highstorm is approaching quickly, and Dalinar is exposed. They race back to the Kholin warcamp, and make it just ahead of the stormwall, but not to Dalinar’s own barracks. They have to take shelter in infantry barracks near the wall. As the storm hits, Dalinar’s vision begins.

Quote of the Chapter:

“You are right, of course, Father,” Renarin said. “I am not the first hero’s son to be born without any talent for warfare. The others all got along. So shall I. Likely I will end up as citylord of a small town. Assuming I don’t tuck myself away in the devotaries.”

Maybe I’ve said this before, and am just endlessly repeating myself, but things are really hard on Renarin. He can’t be a warrior, and not only does the culture he lives in proclaim fighting to be the highest spiritual good, his father is perhaps the most famous warrior of his generation. Renarin is something of a mirror to Elhokar, who is also struggling to live up to his famous father’s name, but with an apparently insurmountable obstacle. This chapter leads me to believe that his “blood weakness” is some kind of epilepsy, as he’s described as being prone to fits during times of high stress. He’s so clearly internalized that weakness as a personal failing, and this quote shows how much that wound is festering in him.

Commentary

This chapter taught us a whole bunch about Vorinism, not only structurally and dogmatically, but also historically. There’s a ton of info to unpack, but I want to start with the thing that irks me the most of all about Adolin, above everything else, forever.

HOW DO YOU DEVOTE YOUR ENTIRE LIFE TO DUELING?! Check this nonsense out:

Adolin grimaced. His chosen Calling was dueling. By working with the ardents to make personal goals and fulfill them, he could prove himself to the Almighty. Unfortunately, during war, the Codes said Adolin was supposed to limit his duels, as frivolous dueling could wound officers who might be needed in battle.

Let me get this out there before I continue: I am all about self-improvement. I am all about setting goals and striving to meet them. But dueling? Really, Adolin? You can’t think of anything better for the ultimate spiritual expression of your entire life than getting offended by other people making snippy comments and then smacking them with a sword until they’re sorry? That is just the worst, except for the even worse fact that you exist in a culture that thinks this is awesome, and a totally valid use of your religious drive.

Dear Almighty, it’s Adolin here. I just wanted to let you know that I’ve been working really hard this week. I think I’ve managed to get even more easily-offended, and it shows! I beat up three other members of your religion because of minor things they said, and proved how incredibly macho I am by use of a stick. I know that in doing so, I have come closer to a true and meaningful understanding of Your Divine Self, and look forward to smacking more people around later.

By contrast, Dalinar’s calling is leadership. With an example like that, how did Adolin screw this up so much? Adolin is also a pretty terrible boyfriend. Hmph.

Now, Vorinism.

Vorinism in its current form is an interesting religion because it’s entirely centered around achieving goals you set for yourself, optimizing a specific ability, and using that to form your own, personal, barely-mediated relationship with the Almighty. It’s a heavily hands-off religion, with ardents functioning not as prayer-leaders or determiners of doctrine, nor as keeper of arcane knowledge, but as guides along your path of self-actualization. This is a pretty nice way to structure things, in my opinion, but in practice the structure of callings is still a heavy determining factor in Vorin cultures. Being a soldier is, doctrinally speaking, the highest Calling, because soldiers are needed to fight alongside the Heralds and take back the Tranquilline Halls. Farmers are next after this, because without farmers everyone is hungry. Very practical. But what this means is that Vorinism enforces warlike tendencies. Soldiers can only achieve their callings during times of war. What’s more, this religion has an inherent bias towards menfolk, as women aren’t allowed to be soldiers.

The reason the ardents are so weak now, and are actually kept as property, is that Vorinism used to be very different. The priests made a bid to control everything outright, and this caused what seems like a global war. Now, ardents are kept very low. They can’t own property, inherit land, they have to shave their heads, and they’re owned by powerful lords. They do not establish doctrine, they just guide others. As we’ll see later, however, the ardentia has found ways around this, and still expresses a lot of political influence.

The Mystery of the Saddle Strap continues to “unfold,” even though they haven’t actually discovered everything. Dalinar and Adolin are being extremely thorough, and it’s a shame that there’s nothing there for them to actually figure out, because I think they’d have gotten there. I do really like the father-son detective team, though.

I find the entire structure that spawned the Highprince of War very interesting. It seems that, in times past, the highprinces functioned analogously to the Cabinet of the United States. This kind of purposeful federalism, where each of the states of the nation is geared towards a specific function, is very easy to analogize to Vorin Callings. It functionalizes people, but also does a lot to force the highprinces to work together. When they have different, mostly non-overlapping functions, there is more reason to cooperate and less reason to feud. Not no reason to feud, of course. That would be way too optimistic and idealized.

In trying to resurrect this system, Dalinar has set himself a pretty big challenge. The highprinces do not want to be subordinate to anyone, with the possible slim exception of Elhokar, and Dalinar is not popular among them. Elhokar’s challenge is probably intended to keep Dalinar busy on a fruitless task.

We are also treated to a view from the highest point of the camps, as well as an artist’s depiction of the camps. They look pretty cool, but make it immediately obvious how strictly separate the armies are. This is not a good formula for a successful war.

That’s it for this week. Next Thursday is July 4th, which is a holiday here in America, so we’ll be pushing the next post by Michael back a week. I’ll have a follow-up article to my ecology primer on July 5th, though, so there will be some relief to your Way of Kings cravings. The article is a little far out there, so I hope it will keep you entertained.

Carl Engle-Laird is the fiction assistant and resident Stormlight Archive correspondent for Tor.com. You can follow him on Twitter here.

I think Vorinism as it exists present day is a really interesting reflection of how society was structured during the Desolations, and I think that we’re given a lot of good hints in this chapter as to how things tended to work back then.

We know that present-day Vorinism encourages people to find their own goals, and work towards accomplishing them. We know that before the Hierocracy, the Ardents didn’t tell others about the theology, but more or less just told you what your goals are, and how to achieve them.

This leads me to believe that Vorinism really does have roots in the Desolations and with the Heralds. I think that at one point, the predecessor of Vorinism (be it a religion, some command from the Heralds, or just tradition) was in charge of deciding how to fragment the needs of Roshar. Pre-Vorinism, if you will, decided that Alethkar needed to preserve the arts of war for when the Desolations would come again. Perhaps it also gave duties to other nations.

It’s interesting to think on, at least, since we know that religion and cultural digression are both heavy themes that BWS likes to play with.

@@@@@ Carl

You make a good argument about dueling. But I (hope) there is one more to it than you think.

You seem to equate dueling purely with the Wester European/American style of insult=fight (usually to the death). There are also duels that were purely for sport and/or competition of self and others that took place in Eastern countries.

These were highly regulated and didn’t need to end with someone dead. Indeed, the duel we see Adolin take part in later on seems more like a mideval tourney than anything else.

For all that, it is entirely probable that the Alethi culture at large really is as messed up in the head and equating fighting people over insults as a religious duty. I’m still not sure what to think about the Thrill beyond a sense that there is something unhealthy about the way it’s being used.

Addendum: Back to one of my favorite subjects with Vorinism and women I have to wonder: how much of the current structure of Vorinism was actually designed by women themselves?

Ardents are the only males allowed to learn all of things actually necessary to run a country–i.e. readin’, ‘ritin’ and ‘rithmatic. And now they are all property.

Women, whether Ardent or not, on the other hand can learn these along with a variety of other sciences as a matter of course; there education seems to largely determined by how much they can afford.

A man may sit on the throne, but is he really king when he entirely depends on his wife, or sister, or mother to tell him what his reports say or to officially write and publish his decrees?

At the very least, that system should make for very good incentive for a male nobleman to try not to piss off the women in his life. Afterall, how would he know if she decided to start skimming from his accounts or publish some scandalous document in his name?

@2. If I’m remembering correctly, we see a duel between lighteyes later in the book. It’s clearly non-lethal. The potential loss of life wasn’t my main concern, though. From how Adolin treats it, Alethi dueling seems very much like an honor-tradition, meant as a socail release valve to prevent feuding after arguments. But to make dueling your purpose is to go looking for arguments, to try to take offense easily. Adolin dedicates himself to a form of violent rivalry and fractiousness that makes him a more volatile component of his society, and his church nurtures that behavior in its leaders.

Carl, I enjoyed your “rant” about the duels, but I tend to see it slightly differenty inspite of your above explanation.

In the duel we see later, Elhokar says how really good Adolin is – so you could treat “dueling” like “our” fencing: excel in the arts of a fighting competition, excel in the discipline it need to be good at it – strategy and tactics where rules do apply. – In this war-driven society it makes sense to accept this (fighting good) as a calling – I doubt his calling would need him to run around seeking insults, though he certainly wouldn’t shy from one.

After reading the scene between Adolin and Kadash I am reminded of a sterotypical movie scene of a Viking feast hall where all the men do is eat, drink and duel. Either that or the gunslinger in the west who always is looking for a duel.

The terain of the Shattered Plains is ideal for Alethi culture. While largly one nation, it is a bunch of atonomous fiefdoms. The creators reinforce this atmosphere. Bunch of camps near each other yet still with defined borders.

Carl, I disagree with your analogy of the different Federal Departments under the US President. I think a better anolgy is the relationship among the States during the Articles of Confederacy. The States had there own monetary system, militia, etc. They needed a confederacy becuase they lacked the ability and strength to function as seperate nations as found in Europe during that time period.

Thanks for reading my musings,

AndrewB

(aka the musespren)

@2 – I read the next chapter this morning, thinking it’d be in today’s re-read, and there is an interesting hint there about the Thrill. Dalinar says that:

Note that at this point, Dalinar is fighting to protect a woman and child. The word “enrage” makes me think of Odium. That indicates the possibility that the Thrill can be used in multiple ways–in rage (or hate), or with honor.

On Adolin: I can just barely wrap my head around how the current state of Vorinism makes dueling a valid Calling, but… I agree, it’s a rather stupid calling – especially during a time of war. Oy. They need a dispensation to change Callings from stupid ones to smart ones… Although I find it hilarious that on one hand he’s in trouble for not making progress on his Calling, but on the other hand, doing so would be counter-productive to the national “Calling” of the Alethi, which seems to be war in general. Catch-22 and all that, and I think it’s funny. (Renarin, on the other hand, is caught in a different and not-at-all-funny dilemma. Poor kid.) Also – yes, Adolin is a lousy boyfriend, but a large part of the problem is that (at this stage) he’s got lousy taste in women. Sheesh.

Vorinism… Yes, indeed. It’s a problematic religion, isn’t it? I think Brandon did a great job in creating this one, with its comprehensible but error-ridden development from its origins to the present. Given what we’re told later about the Ten Kingdoms, and the purpose of Alethela in the arrangement, it makes sense. It’s just twisted, because the means have become the end. It’s a very human thing to do with religion, because simply keeping the forms is so much easier than understanding their purpose.

Now to read the comments that showed up while I was reading the post…

The way I read it, Adolin is supposed to minimize his dueling because his father enforces the Codes on him. The rest of the Alethi don’t follow the Codes, thats why, the ardent asks Adolin about it. For “normal” Alethi it’s still fine to duel, even in times of war.

It was a long time before I was able to view Adolin in even a remotely favorable light after reading that he had chosen “dueling” to be his holy calling. Yes, yes, the Alethi value war and battle prowess above all other pursuits. Still ludicrous.

@2. wcarter Those are some interesting thought regarding women in Vorinism. This isn’t the only series that Sanderson creates a religion that separates the duties and abilities of men and women, but it’s by fa the most interesting ( for one would hate not being able to eat spicy foods). But If women had a hand in creating the structure of Vorinism, it seems odd that the “safe hand” feature would be so prominent in it. It seems such a large handicap to impose, not being able to fully use of your hands. I have a hard time believe that women could have had a string role in creating Vorinism and have allowed the “safe hand” feature.

I just have to point out something that I think BWS did on purpose here, and that seems to have direct impact on the way that we understand the Alethi culture.

Carl says

Seemingly very lauditory to this type of religious action, yet, if I may be so bold, it is also clear that Adolin devoting himself to Dueling

(HOW DO YOU DEVOTE YOUR ENTIRE LIFE TO DUELING?!) is largely determined by the very fact that the religious hierarchy is so hands off. BWS is clearly playing with ideas of what will happen when a religious structure is completely gutted of institutional authority and democratized to the point that whatever the individual likes or loves or wants can be shoe-horned into religious devotion. Thus, ironically, the angst expressed over Adolin’s choice may perhaps be better pointed at the religous structure?

All in all, I agree that this is a very human thing to do. People are always looking for and expressing religion in ways that are outside accepted orthodoxies. Making religious belief and practice wide enough to include all of these practices means that you must accept even the ones that are problematic and potentially dangerous.

Also, it is very clear that this is a devolved form of social structure from the institutional structure of society under the KR/Heralds. The Alethi are the inheritors of the social roles of protectors that have become warped over time to the point that they are glorifying those things that were anathema and meant to be tightly controlled before, all in the name of their religious “callings.” Which is interesting as we see the Shin who have done the same thing, but in a different manner (fighters on the bottom leading eventually to the status of truthless, those who add on the top). (This is me agreeing with Wet’s points)

I would also agree with @2 and 4 that Adolin’s dueling can be cast (and is seen to be such) in a more civilized and healthy manner.

Wet@7 – again the problem is that the institution (Ardentia, which although some have used the word ‘church,’ I don’t think that fully encapsulates what the institution is) cannot issue such a decree because the political Powers that Be won’t allow it. So not only is Adolin in a Catch-22, the Ardentia is as well. If they truly wish to help people individually and their society develop in the right ways, they will have to buck that society that tells them they can’t do that.

@2 – I like your wonderings about Vorinism and women in general. They are important questions to be asked. From our 21st C (largely Western) mindset, it is probably intuitive to think that the men have pushed the women into some role, etc. Yet, it seems that in the case of Roshar, and the Alethi/Vorin kingdoms in particular, the women are the real power as they are the only large body that can assimilate knowledge/information. We even see instances where women write things that are, by practice and unspoken agreement, never to be read outloud or to a man. Shallan reads this portion in the biography of Gavilar that Jasnah wrote. In such a case, it is more probable that it was women who forced men into having such a limited role. (“Really, honey, you just go and practice swinging that sword, I’ll be right here doing all these other important things…” or “Man, what you doing out of your armor? Get back outside and go kill me something to eat, while I write/read this philosophical/political/historical treatise that will guide the development of our entire nation, paint/sculpt/create the art and religious iconography that will influence millions, and if I get the time, I’ll oversee the financial institutions and manage our trade holdings. If you’re a good boy, I’ll tell you what to say when you get back so you and others feel that you are intelligent.”)

Similarly, I think it is important for us to note that we only really see Alethi culture and Vorin social structure through the eyes of males at this point. Jasnah doesn’t ever really speak or think about it, and Shallan is not a very reliable source due to her family life and deeds. (Is it odd that all the main female characters are rebels against this system to one extent or another?) Thus, any complete condemnation of Alethi culture, based only on the male arts of war, seems a bit preemptive as we are seeing only one side of a highly bifurcated social structure. Having said that, yes there are plenty of things wrong with the male-centric side vis-a-vis war, destruction, etc.

Which is why I personally think that Dalinar’s character is extremely interesting (I know others can’t stand him). He is fighting against the grain in this regard, wondering why all a man is supposed to do is fight and kill. In this regard, I also see Renarin becoming an extremely important character as he has had those things placed out of his control/capability. Characters (and people) grow through adversity…

@10 Ciella

Excellent point about the safe hand. The best counter I can come up with is one can never underestimate the influence of pride on self-handicaps (men like to say we can take others in a fight “with one hand tied behind our back” afterall).

@11 sillyslovene

Thanks for pointing out the undertext in the books. I had forgot to mention those.

I wouldn’t go so far as to call Shallan a rebel against the system though. Girl is deeply religious and we haven’t seen anything to indicate she is at all interested in trying out any of the “masculine arts.” It is true however that she is a thief and a liar, so take that how you will.

As for Jasnah, she’s agnostic true, so I’m sure the Ardentia at least consider her a “rebel”, but she’s also civil and follows the normal cultural mores.

She just doesn’t feel that evidence points to the actual validity of Vorinism.

In any case, I want to learn more about how this society works. In particular, I would like to see more members of the Ardentia–both male and female–who aren’t actually Ghost Blood assassins in disguise.

And with that I’m going to shut up for while.

@11 sillyslovene – Regarding what you were saying about the unspoken text in books, I also saw this as the females essentially hiding things from men, which would indicate that they are much more in control than the men are, but are a bit secretive about it. It’d be nice to get more perspective from female characters about this, though.

smintitule @1 – The Knights Radiant in Dalinar’s “Midnight Essence” vision pretty much told him that Alethela was given the job of studying and maintaining the arts of war, prepared to teach the others when the Desolations came, but otherwise making it possible for the other nine kingdoms to leave in peace between the Desolations. It was strongly encouraged, if not enforced, that anyone who felt the desire to fight should come to Alethela. (Interestingly, I just noted in that passage that the KR says that “Fighting, even this fighting against the Ten Deaths, changes a person. We can teach you so that it will not destroy you.” This bears further thought…) She doesn’t say exactly what the other nations were given to do, if there were specific tasks assigned or not, but Alethela certainly had a specific role.

As you say, religion and cultural digression are significant themes; in this case, he’s giving us a lot of hints as to the origins, which should give us some insight into what’s wrong with it now.

wcarter @2 & Carl @3 – I spent some time scrounging through the text to see what I could find about dueling, and got some interesting results. It’s all set up as a competition, all nice and friendly-like, with statistics and rankings and formal judging; most of the time, the dueling is done with dull, chalk-coated dueling blades, with the scoring based on the white lines you leave on your opponent’s clothing. It appears that a fair number of the duels are simply friendly bouts, but there’s a significant amount of claiming insult going on, too. It even looks like some of the “insult” bouts are disguised as friendly, and vice versa. But it’s all formalized competition.

The one that really got me, though, was the way the Shardbearers duel: full Plate and Blade, and “the winner would be the first one who completely shattered a section of the other’s Plate.” Say what?? In time of war, you’re dueling to shatter someone’s Plate, which takes time to regrow and in the meantime leaves him without effective armor? You’re going to take one of the relatively few Shardbearers out of any needful fighting for a couple of days – for a stinking duel??? ::shakes head in disbelief::

Also @2 – I find it most interesting, the way Brandon has set up the male/female roles in this society. Just about the only significant thing the women don’t do is fight, and for a man (at least, a lighteyes) to do anything else pretty much requires him to be an ardent. I agree: whatever the nominal titles, the women hold most of the actual power in Alethkar. They may not even think of it that way, but the men are totally dependent on the women for most of what makes up “civilization” – arts, engineering, mathematics, literature… I still find it moderately stunning that otherwise intelligent men don’t want to learn to read and write. Amazing, what cultural preconceptions can do.

smintitule @6 – Thanks for that quote – I think it’s one of the formative aspects of my “intuition” that the Thrill isn’t necessarily a bad thing. At least, I’m convinced that it’s not “of Odium” the way some people theorize. (I use intuition rather loosely there; what I mean is my perspective on something, formed by my reaction to different things I’ve read, though I might not remember the specifics. In this case, I’m pretty sure this was one of the things that steered me toward thinking that, at least in origin, the Thrill was a positive thing.)

Ciella @10 – You might consider this quotation:

sillyslovene @11 – Good thoughts, there… I especially like the idea that Renarin may be an important character more due to his limitations than his strengths.

On one hand, I do have to agree that dueling is a vapid and shallow calling. But on the other hand, this is largely the kind of women that we see Andolin pursuing and/or surrounded by. If this were more modern times, they would probably all be blond cheerleaders saying things like, “Like, so, ya’ know?”. That might be a little harsh… but it is as much a mirror on Andolin as it is on Vorinism or Alethi culture.

Vorinism reminds me of Port Chester University from the movie PCU “where you can major in Gameboy if you know how to bulls…”

As for the safehand vs. strong influence of women thing, keep in mind that inconvenience does not always trump religious tradition. There are millions of Muslim women today that if suddenly in power would keep the veil. Sure the practice would probably end eventually but it could take many generations.

Thoughts:

Dalinar and Adolin pass “a group of stonemasons carefully cutting a scene of Nalan’Elin, emitting sunlight, the sword of retribution held over his head.” Could this be the same “relief of Nalan’Elin” pictured before chapter 69?

Second, do “Elevations” make anyone else think of leveling up in games?

@17 – Pre-videogame societies tend to use religious progression to feed their RPG needs.

I kid, I kid.

Regarding the scene of Nalan’Elin, though–wasn’t Nalan the one that is supposedly going around destroying artwork of himself? Or am I mistaking that with another Herald? If it is Nalan, that relief would give Nalan an excellent reason to visit Elhokar.

@17 – I think that is supposed to be the same relief. and 2- that’s a pretty interesting observation. Given what happens to Kaladin (and the ‘leveling up’ he gets when he recites the 2nd Ideal, this makes me think that the whole calling and elevations idea derives/evolved from the (gradual?) training and initiation that were standard for the KRs. Literally, during the times of the KR, when someone met their goals and/or achieved a higher state through internalizing and reciting the next Ideal they achieved a “level up” which brought greater power. I like it..

@18: It’s Shalash, so this particular relief is probably safe. Perhaps she will still show up, though; there are apparently a lot of them, some presumably depicting her.

@12 I think Shallan is a bit of a rebel. She’s certainly not conforming to what women are expected to be: She killed a man. Not just any man, her own father. She owns a shardblade. And she’s taken responsibility for saving her house, rather than leave it to her brothers with her simply supporting by scribing for them. And she’s plotting to steal a sacred item of great value. All fairly rebellious in the context of Roshar, and especially so when you consider the way the minor character women are portrayed at Elhokar’s feasts. Shallan, Jasnah and Navani really do break the mould.

@14 Just to expand in what’s been said, just think of Adolin as a martial artist and suddenly it makes much more sense – his calling is to master the art of dueling (the rankings are like modern day world championships).

It just so happens that it’s culturally acceptable to use martial arts to beat up people who annoy you (as long as you formally challenge them and give them time to prepare)….

So while only moderately practical, it makes way more sense.

@22, also many regarding duelling as Adolin’s calling

I honestly tend to think of Adolin’s choosing his calling as duelling to be more akin to choosing “football” as your calling, and then your father says “No playing football when we’re at war, you could get hurt when there are more important things going on”.

Sure, maybe it’s a little bit stupid and meatheadish to choose something arbitrary like duelling as your calling, but it’s not like he’s making retribution for the tiniest slights into his religion. He’s just turning the equivalent of football into his religion.

@23: Isn’t football already a religion? :D

I find it notable that only Dalinar is doing the paperwork. Sure, Sadeas pays his taxes (which in any context would be HIGHLY if any of the other Princes thought about it), but while Sadeas is plotting, Dalinar is metaphorically making the trains run on time. One wonders at the possibility of how the kingdom would have collapsed if Sadeas had succeeded in offing Dalinar, since then no one would be taking proper care of the paperwork. Elkohar certainly wasn’t doing it, not sure Navani would have though she likely would, and by the time Sadeas noticed it needed doing… ugh.

Anyone else wonder what kind of woman Elky’s wife is? After all, she’s essentially ruling all the non-military parts of the kingdom in his absence. Which makes everyone”s comments about how women hold all the non-military pwoer and how Dalinar’s implicit statement about having a (female) scribe you trust all the more… significant.

And not ALL the reading and writing is done by women. Shallan makes comments of men who CAN read and write, but need to keep it secret. The tone implied it’s the cultural equivalent of men wearing women’s underwear: it’s thier kink, but it would be scandalous if it got out, even if it were harmless, and people will pretend not to know you. Remember at how shocked Adolin was when he thought Gavilar could write?

Makes me wonder how much Szeth knows about Alethi culture, if our anime-ninja expy didn’t know men didn’t write.

I’m included to think in ye olde Desolation times, while Alethela did war, Shinovar did farming, hence why their current cultures are as they are. And while Althi would keep farmers elevated 2nd highest calling since they’d understand the logistics of needing people kept fed, Shinovar, positioned so remotely as it is, would not see soldiering have to do with farming, and react accordingly. Makes me wonder what the other cities ye olde expertise were. Off the top of my head, I can think of transportation (Urithiru), medicine/healing (Karbranth?), intelligence gathering, Research and Development or at least Manufacture, and, depending on Honor’s position on it, Assassination.

And am I the only one who keeps envisioning Dalinar as either Morgan Freeman or Samuel L. Jackson? Yes, I know that’s not thier coloring, but if they could do it to Nick Fury…

Since light (blue, green or grey) eyes are rather critical to the character… not really. My first mental image was a 20-years-ago Derek Jacobi.

I think everything that I would have said about duelling has already been said, so I’ll leave that alone (for the record, I would agree with the points made by Erunion @@@@@ 22 and smintitule @@@@@23)

It still bugs me that Elhokar set up the whole Strapgate thing himself. I mean, really, not only are you potentially putting your own life in danger, you’re casting suspicion on your most loyal followers. Oy vey.

@@@@@24 – I suspect your opening comment is truer than you realize…

As always, I am very intrigued by the way specific jobs/abilities are broken up in this society, whether that’s by gender or through the different roles of the various Highprinces in the old days. I wonder how quickly the men in general would notice how little ultimate authority they had in non-military matters if they ever got an extended period of peace. I don’t necessarily have a problem with specific gender roles per se, but keeping half of the population illiterate doesn’t seem like the greatest way to build up your society…

The Herald icons for this chapter are Chach-chach. Once again, they seem to be associated with Adolin.

For another point of view, in “The Curse of Chalion”, by Lois McMaster Bujold,

This is an important reason for this prohibition in the codes.

Although, among the Alethi, one can never be too sure never whether a neighboring highprince is enemy or ally. It makes a difference if the dueling is nonlethal, but it isn’t always. The potential damage to shardplate, thus weakinging shardbearers in case their armor is actually needed at a crucial moment, is another supporting reason for this particular provision if one were needed.

The way the Alethi highprinces are conducting this war is none too wise, (apart from vengeance being in my opinion a poor reason for warfare in the first place), and it’s already been established that the Alethi in general are not following the Codes.

Something about the ardent’s account of Vorinism sounds suspiciously incomplete, given Dalinar’s visions and Kaladin’s riding of the storm (later). Suppose that Vorinism once did have true prophecies…which had ceased in the absence of the Almighty/Heralds. By the time of the Sunmaker, the ardentia had begun manufacturing them instead, and discovery of the deception discredited the whole idea of attempting to see the future.

I expect the various ways in which religion can become twisted or corrupted over time to be a significant theme in the Stormlight Archive.

On the whole dueling thing, I’m pretty sure in the chapter up ahead where Adolin duels another lighteyes, there are references to a much more formal structure for dueling. Some talk of rankings, and I believe Elhokar saying something along the lines that Adolin is good enough to become Champion if he was given free reign to pursue it.

This to me indicates that dueling isn’t just a way of handling argument resolution with violence, but instead a major centralized sport within the nation. In that way, Adolin chosing to devote his life to dueling is no more frivolous than someone today deciding they want to be an Olympic Fencer, or really devote their life to any sort of sport.

Also, I’m not certain, but I do think that a Calling can change. I have no text to back that up, but can you imagine being stuck with the same Calling from when you first become old enough to choose one (figure about 14-16 in this culture?) until the day you die? So as a young hothead who just wants to fight, Dueling is his calling. In his later years, he could easily change to Leadership or whatever else.

On the other hand, if it’s not something that can be changed, it could explain Adolin’s choice of calling. The War would have started when he was 17, if he had turned 16 in a time of peace and chosen Dueling so he could follow in his father’s footsteps as a great warrior, only to have a big war break out a year later? Well now he’s stuck in a Calling that he has no real capability to pursue. He’s devout, so he still practices, and he has talent (takes after his dad), so he’s quite good at it, but he’s not free to fight his way up the ranks as he would have been had the War never started, due to his father’s restrictions against duels.

Anyway, point is I can see a number of ways it could be justified, I think Carl’s reaction here is a little over the top.

@29 I believe that a calling can be changed. The ardent that Adolin speaks to was once a soldier, but he changed his calling to become an ardent quite late in life. I need to reread this bit though to see if it gives any more info than that as I can’t recall the details precisely.

Impractical clothing is common as a status symbol. Lower-class women only wear a glove that allows them to use their hand for work. Letting men handle the hard work while women show with their clothing that they can afford to let others work for them reinforces that women are the real power. In old cultures like the Greek or Romans work was for slaves while important people could afford to wear impractical togas.

@31 birgit – That’s actually a really good point, I hadn’t thought of it that way. While we do have quotes from Brandon stating that wearing the cuff over the safehand grew out of the tradition that all feminine arts can be done wiht one hand and little work, it is entirely possible that this mentality matches the Greek/Roman one that you describe.

I don’t know if this idea has been thrown around yet, so I will drop it here.

In regard to the Thrill (as well as specific assignments to nations) is it possible that Honor gave the Alethi the Thrill originally because they were chosen to fight? If, indeed, Honor gave them the “calling” to fight, it would make sense that Honor would also give them a psychological reward for fighting. Later, Odium may have changed and corrupted this feeling.

Also @14 Wetlandernw, the idea that “fighting […] changes a person” may have something to do with this. Could this change be the start of the Thrill? This also reminded me of the discussion about first time Kaladin used a quarterstaff. That fight certainly seemed to change him and contained several “Thrill-like” elements.

This is just a jumble of thoughts seemed to fit together, hope it makes sense.

@33 I like that idea, I was entertaining similar thoughts. BWS often has a concept or power twisted in some way(e.g. allomancy and feruchemy, then hemalurgy with similar powers but using destruction/death to acquire; AonDor and the power of the Dakhor priests to resist it and use a similar power through destruction/death). So perhaps Odium doesn’t just have opposing forces for the forces of Honor (and Cultivation?), but has twisted Honor’s power now that Honor is dead.

Journey @33 – I think it’s entirely possible – even probable – that most of the things we see as twisted were originally positive things, gifts of Honor and/or Cultivation to those who defended humanity on Roshar. Whether they were deliberately twisted by Odium, made susceptible to it by the Heralds abandoning the Oathpact, diminished by the Recreance… how, or when, or why, or by whom, we really don’t know yet. But my bet is that the Thrill was once a good thing; it may well be part of the background to what the KR says to Dalinar in that quotation.

It’s pretty easy to say that killing has certain psychological effects on a person; it may well be that on Roshar during the time of the Radiants, it had a more profound or “magical” effect on them, which could only be mitigated by the kind of training the Radiants could provide. I do hope we learn more about it soon.

HI all, BWS web sight has a posting that people should read, its not related to our discusion but it is neccasary.

I dont have much time but 33-35 I like where you took this ,I just wanted to add that during one of dalinars visions we see a KR telling him that the KR could teach him how to keep the thrill from destroying him this leads me to think that the thrill could be used with the proper training. So using it to protect would keep you safe , and using it to kill because you just can, or with bad intentions would destroy your soul.

I missed somthing in the last read that made me wonder what the Alethi feel about. Adolin and the ardent are talking and they are walking by sculptures that depict the hearlds which are 5 femal and 5 male figures, so how do the Alethi explain that one. I contradicts voranism and gives an inroad to dalinar for female warriers. I cant believe i missed that.

Asfor changing your calling Shallon was was aproched to change her calling also.

I wonder if the Hierocracy of Vorinism was an actual nation-state with armies and borders, or just simply a religious movement. Did it seek to conquer the world through armed force or honest conversion? Given that much of Roshar’s history has been lost and distorted I don’t know that we’ve been told the “true” story of the Hierocracy. It is still an interesting institution. It seems that Vorinism is still very organized and structured but went through a doctrinal shift.

Other thoughts: Is every ardent owned by someone? I wonder what the slave culture is like in Roshar. The ardents seem pretty favored and even the bridgemen draw pay. It reminds me of the slave system in ancient Rome. Many slaves did grunt work, but educated slaves were used to tutor and help run the household/business. IIRC they could also buy their freedom. I also wonder how many slaves of any type Dalinar has. He freed the bridgemen, but does he use slaves to work his lands?

37 Giovanotto Somewhere it states tha Dalinar does not keep slaves , im pretty shure that i’ve seen that in the book when the bridge men are talking to Kaladin.

Re safehand discussion

There is much more to this that we don’t know yet. I can’t get it out of my head that it would be a perfect way to hide some sort of fabrial that is worn on the hand like a Soulcaster.

SCM @@@@@ 24

Your description of the 10 kingdoms makes me think of the districts in The Hunger Games.

So, has anyone been over to Brandon’s website recently? There are some progress bars that are showing 100% now :D

jeremy @40 – I saw that this morning! He also tweeted that he’d sent the first draft to his editor. :)

Thanks for the heads-up. It’s funny that amazon has the publishing date of the english publisher in november, while tor’s is still listed as january as Carl told us. – There’s still hope that they’ll meet in the middle and give us a christmas present…

Ok, I’ve kind of pulled ahead of the reread again, but I’ve found something interesting in one of the epigraphs. Someone mentioned the thought that Urithiru may have been above the shattered plains. I thought that a nice idea at the time, but this epigraph indicates that that can’t be the case. It’s the one at the start of ch 35 and says: Though many wished Urithiru to be built in Alethela, it was obvious that it could not be. And so it was that we asked for it to be placed westward, in the place nearest to Honor. If Urithiru was built in the west then it definitely was not in Natanatan or Alethkar. I’m half wondering if it could have been near Shinovar then?

QueenofDreams @43 – Well, one thing in favor of Shinovar is that mountain range; some of the historical stuff claims that Urithiru was inaccessible by foot, but Nohadon says he “walked from Abamabar to Urithiru.” The mountains, especially if they were more rugged 5000+ years ago, might make people generally think of it as “inaccessible by foot.”

On the other hand, it seems silly for there be thrones for the ten kings of the Silver Kingdoms there, plus the center of the Orders of Knights Radiant, if it’s so hard to get to; on the other hand, there looks to be a lovely natural harbor at each end of the kingdom, so maybe they came and went by ship.

Near as I can tell, it’s as good a theory as any, and better than most.

I was thinking of the mountain range as well Wetlander. Maybe he walked to the mountains then had to get some kind of ‘teleport’ up to the city proper? OK now I’m just getting ridiculous. I know. And I know it makes no sense to have the home of the radiants, and thrones of the kings so far from the centre of things, but as the reason for placing it there is to be ‘in the place nearest to Honor’ I guess that would be a secondary concern? Also if they truly had means of instantaneous transport through these ‘oathgates’ then maybe that’s not so much of a consideration as the distance would be negated?

Wait… So we know that Honor was in the west? That seems significant. If the Origin is in the east and Honor is in the west, then it seems to support the idea that the storms are not of Honor.

While I think that the storms are of Cultivation, I have always thought that the stormlight is of Honor. Now I am wondering why the Origin would not have been the place on Roshar closest to Honor.

If the world is round the eastern and western “end” of the world could be the same thing.

Another thing to consider is that is was built in the “place nearest to Honor” at the time. It’s not impossible that Honor was hanging out with Cultivation in Shinovar most of the time and then went to do battle with Odium over in the east. I don’t think we know exactly when the highstorms started, or if they’ve been going all along (although it’s possible that’s mentioned in one of Dalinar’s flashbacks and I’ve forgotten it).

Queen@45 – I wouldn’t mock your “teleport” theory so easily.

In addition to the oathgates (which I agree, hint at teleportation), when Teft is listing some of the legends of the KR to Kaladin, I believe he lists: flight, walking-on walls, move great distances in a single heartbeat, make stone melt by looking at it, command the sunlight, etc.

So, some form of travel/teleportation does seem to possibly be in the KR and Herald’s repertoire.

@39: That’s essentially what Shallan does – most of the time she doesn’t wear the stolen fabrial to use it, but she does keep it in her safepouch after awhile, and she thinks about it several times as a good place to hide things where nobody would invade her privacy. It also describes her “clutching” the safepouch a couple times, so it’s clearly a little pouch within the sleeve that she can hold in her hand if she wants, or not, and because the sleeve is buttoned closed, it won’t fall out. (Then it’s also with her later when she thinks Jasnah needs it to heal her.)

@47: I’m thinking that too. It’s clear that the highstorms go around the planet in the same direction every time, but they could start on the other side of the planet. It’s clear that Kaladin is amazed at the distance he covers during his “flying with the wind” vision. There’s a lot of planet out there that most of the characters we know aren’t very familiar with.

I also have to wonder how much men even allow themselves to look at maps, given that they usually have written labels for places. Kaladin certainly isn’t very familiar with geography beyond what he’s personally experienced, which mostly is just Alethkar and the Shattered Plains. But Dalinar and the high princes have a map of the currently explored plateaus of the Plains, and they have to be able to get to the right one when a chasmfiend is sighted. Also, even though they don’t do actual mathematics or finance, they have some understanding of how they work – Dalinar understands how taxes work, and Elhokar charges the high princes for Soulcasting. And they can all do basic counting – the bridge crews are numbered, and so are the plateaus. It’s actually kind of baffling how they can learn a lot of conceptual ideas, enough to be able to listen to books read to them, without standard education that includes reading.

I’m going to add to Confutus’ chapter heading comments again – I don’t think this is Chach-Chach – I’m pretty sure it’s Betab-Betab. Betab’s characteristics are ‘Wise and careful.’ When I think of the chapter’s events with Betab in mind, I think of the lessons that Dalinar is trying to impart to both his sons and to the Alethi at large.