In the transcendental year of 1999, it became clear to me that I was extremely cool.

No, that’s a lie, please don’t take that declaration even remotely seriously. I was twelve and thirteen years old in 1999, and no new teenager understands coolness on a base level, much less feels that coolness in their still-growing bones. The effortlessness of cool is not something that any tween can hope to emulate, the style inherent in the word “cool” has not yet developed by that age. So I was not cool. But there are now two solid decades between me and that year, and on reflection, I’ve realized something momentous:

1999 was the year when I got a glimpse of my future. And I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one.

If you asked me point blank, I’m not sure I could pinpoint a time in life when the words “nerd” or “geek” were affixed to me, or even when I learned what they meant. There were a range of odd stereotypes that accompanied this identity, many that I had never experienced for myself—I was never stuffed into a locker, I never bonded with my friends via long hours playing video games or DnD, I was never been publicly ridiculed for wearing glasses, and I had never been cast aside by a cute girl for some buff jock. (The “nerd” experience has long been presumed cis, straight, white, and male, so that probably had a lot to do with my disassociation.) My markers were simpler than that: I had obsessions and I talked endlessly of them; I memorized all my favorite scenes and quotes from movies and books; I wasn’t much of an outdoors kid; I really really loved genre fiction. When I finally understood that most people didn’t mean the term “geek” affectionately, it was far too late, as I was firmly entrenched in a subculture that still refuses to relinquish me to this day.

It’s still weird, if I’m honest. Knowing that I’ll always belong to this category of human, perhaps more than I’ll ever belong to another one.

There wasn’t an overabundance of outright cruelty for me, more a constant stream of little digs about what I liked and how I chose to spend my time. But the idea of conforming to a different set of standards in order to mitigate petty insults never sat well with me—I have an ingrained knee-jerk reaction against being told what to do, even in the most mild scenarios. So I watched Star Trek on my own time, and wrote fan fiction in a notebook, and had stealth cosplay days at school with a couple of close friends. Life moved along and I became more and more of a person each year.

How could I have known that 1999 was on its way.

Since the advent of the modern blockbuster (often cited as Steven Spielberg’s Jaws in 1975), science fiction and fantasy have been mainstays of pop entertainment. Star Wars only solidified this, and every year there was inevitably a Terminator, Back to the Future, or Princess Bride ready to make millions at the box office. But they were commonly viewed as fun “popcorn films” and not meant to be taken seriously in regard to the overall cultural zeitgeist. Despite this insistence, SFF began spreading on television with the resurrection of Star Trek and the advent of the SciFi Channel, which started broadcasting in 1992, and began creating original content in the late 90s.

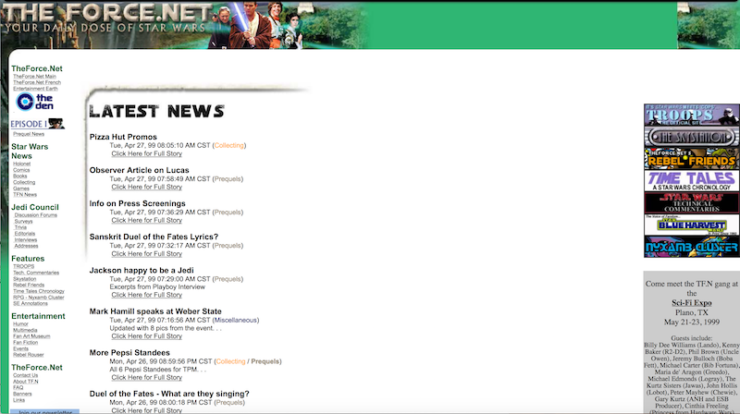

Soon the end of a millennium was upon us, and the internet was steadily blooming into something that would take over most of our lives. But we weren’t at peak saturation yet. The Dot-com bubble and Y2K were close to exploding all over us (one of these would actually affect the timeline, the other would decidedly not), and CGI was quickly blowing its own bell curve in terms of believability. I watched movie trailers on QuickTime, and spent hours on fan sites with the same five pages and forums where you could talk to other anonymous friends. All parents were convinced that their children were going to be kidnapped by people from chat rooms. My mother didn’t realize that the sort of predators she was worried about didn’t tend to show up on TheForce.net.

So what made 1999 different? It was a level of saturation (and sometimes of quality) that made it clear to my twelve-then-thirteen year old brain that the things I adored were about to get mainstreamed, and fast. Imagine being twelve years old and suddenly the first season of Farscape and then a film called The Matrix get dropped on you like meteor. I had been waiting for Farscape, to be fair—the instant I saw the commercials for it, I was hooked on its possibility, and it never let me down. But The Matrix was something else entirely. That movie was an unqualified moment in science fiction cinema, heralding a near-decade period when geek guys were never found out in public without their black trenchcoats of varying fabrics. While I enjoyed the film thoroughly, it was a little too grim to grab me quite as hard as it did for so many. But it led to the strangest change of all: people who thought I was incredibly weird suddenly wanted to talk to me, specifically about that movie.

The Mummy arrived in May and promptly took over my brain. (It was a banner year for Brendan Fraser, between that, Blast From the Past, and Dudley Do-Right.) It glorified camp in a way that was very much My Thing, and I went to the theater to watch it again several times. The saddest thing about The Mummy to my mind is that no film since has replicated such a winning formula for action flicks; in the new millennium, action moved further into the realm of realism and lost a lot of that awkward delight and over-the-top pomp. (The Fast and Furious franchise qualifies for some of this, but it’s considerably more Tough Guy than The Mummy was trying to project.) I probably listened to that Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack one hundred times in one month on my skip-resistant Discman. It seemed like an embarrassment of riches already, but it couldn’t quash my need for Star Wars: Episode I—soon to be one of the most derided films of all time.

Here’s the thing about being a kid when bad movies come out: if it’s a thing you adore, it can be really easy not to care how mediocre it is. All the chatter about it how it “ruined Star Wars” never mattered to me. I got a Star Wars movie in 1999, and that was what mattered. I got to dress up as Obi-Wan Kenobi for a movie release, and that was what mattered. A new Star Wars movie meant that kids who knew nothing about Star Wars were constantly asking me for context, and that was what mattered. Star Wars was firmly reintroduced to world again, and I had more to look forward to. That was all that mattered.

I noticed the horror genre was trying some new tricks on for size, too. The first half of the year I couldn’t turn my head without seeing some form of viral marketing for The Blair Witch Project. (Do you remember how the IMDb page for the film listed the actors as “Missing, Presumed Dead” for the longest time?) Some people got taken in enough that they bought it, thought they were looking at actual found footage from some poor dead teenagers who got lost in the woods. The film’s ad campaign jump-started a new era in meta marketing, immersive and fully aware of the power of the internet. There was a “documentary” on the SciFi Channel that further built upon the legend of the area, something that I kept flipping back and forth to while channel surfing. It never occurred to me that this would become a roadmap for everything from low-budget oddities to Batman movies, harnessing the natural curiosity of fans the world over.

In 1999, my thirteenth birthday fell on the day that three different SFF movies were released: The Iron Giant, Mystery Men, and a little Shyamalan film called The Sixth Sense. I chose to see Mystery Men on that day, perhaps the least remembered of the three (which is wrong, that movie is beautiful). But The Iron Giant snared countless hearts that year, and The Sixth Sense was just like The Matrix—for a few months it was all anyone could talk about. Every single late night talk show and award ceremony had to do a parody of “I see dead people”, in Haley Joel Osment’s frightened little voice.

There were other weird standouts for me that year that I still can’t explain in terms of how well I remember them—The Haunting (a remake of the 1963 film of the same name, itself adapted from—but barely resembling—Shirley Jackson’s masterpiece The Haunting of Hill House), Bicentennial Man, Wild Wild West (I’m sorry, it stuck somehow), and Stigmata. And then there were some that I was too young to understand fully; eXistenZ was a bit beyond me, sad to say.

There were plenty of forgettable films, from Wing Commander to a cinema adaptation of My Favorite Martian, in case we were worried that SFF was leaving its B-movie roots behind.

One of the biggest award nominees of the year was a film based on Stephen King’s The Green Mile, and the adults around me talked endlessly of Michael Clarke Duncan’s moving performance.

As a fan of Tim Burton for basically my entire life, the arrival of Sleepy Hollow around Halloween felt like a glittering gift.

But perhaps that greatest portend of things to come happened on Christmas that year. My entire family woke up with a terrible cold that morning, and decided that we’d prefer to spend the day going to see a movie, forgoing the usual holiday complications and entanglements. On that that day, a little film called Galaxy Quest came out, and as a fan of Original Series Star Trek, that seemed as good a choice as any. My parents and grandmother and I sat down in a darkened theater and then never stopped laughing.

Looking back, Galaxy Quest was an omen, the truest harbinger of things to come. In a year full of renewed franchises, surprise hits, and silly revamps, here was a film that turned a metafictional eye on not only science fiction, but on fandom—the unsung engine behind every blockbuster smash and cinematic universe. Galaxy Quest is a film where the passion of fans is ultimately what saves the day, in a narrative that gives them that heroic sponsorship without condescension or belittlement. In effect, 1999 ended on this movie. It ended on a message that spoke to the power of fans and the power of science fiction when appreciated and harnessed by the people who loved it most.

When I was thirteen, I didn’t really get that. But I did know that if those awkward kids who adored the Galaxy Quest TV show were heroes, then this movie thought that I could be one too. I knew that what I loved was being embraced on a level I had never seen before. I knew that there was something deeply powerful about the excitement I was witnessing. And I knew that 1999 felt very different from the years proceeding it.

These days, being a nerd is something altogether different. It’s expected, maybe even “normal” to a certain degree of obsession. It’s all around us, and getting harder to keep track of all the mediums, stories, and universes. But I remember when that train picked up steam. Before anyone guessed what was coming. And I’m still awed by what I saw, twenty-plus years down the line.

Originally published July 2019

Emmet Asher-Perrin will never stop inducting children to the wonder of The Mummy. You can bug them on Twitter, and read more of their work here and elsewhere.