Mark Twain, like most writers of any quality, had preoccupations. Mistaken identity, travel, Satan, ignorance, superstition, and childhood are all pretty obvious ones, but the most fun one is Twain’s almost obsessive preoccupation with what other writers were doing and why they should (or shouldn’t) have been doing it. Occasionally he wrote essays and articles to this effect (if you haven’t read “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” please do so this instant), but he also spoofed writers all the time.

Though many of us might recall the more serious aspects of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from sophomore English, Tom and Huck were some of Twain’s favorite spoof tools, and the four little known late novels about the duo (two complete and two incomplete) are what I want to make sure you know about: Tom Sawyer Abroad, Tom Sawyer Detective, “Huck Finn And Tom Sawyer Among the Indians,” and “Tom Sawyer’s Conspiracy.” First up: our duo board a balloon in Tom Saywer Abroad.

Tom Sawyer Abroad (1894) is Twain’s take on the adventure story. It occurs very shortly after The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and, like all of the novels except The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, is narrated by Huckleberry Finn, in spite of the fact that he concluded TAOHF by telling us in no uncertain terms he’d never write a book again.¹ The boys and Jim have returned to Petersburg and are celebrated for a short time for their travels and hijinks, but Tom, who has a bullet in his leg and works up a limp to make sure no one forgets it, is celebrated most of all. Tom loves the attention and keenly feels the burn when his closest competition for Most Traveled and Celebrated Petersburgian, a post master who has traveled all the way to Washington DC to confess to the senate that he never delivered a properly addressed letter, announces a plan to go to St. Louis to see an airship that will be traveling over the globe. Tom implores Huck and Jim (who is free, remember) to accompany him to St. Louis; when they see the postmaster touring the small, hot air balloon-like ship, Tom urges them onto the ship itself and insists on being the last ones off, so as not to be outdone.

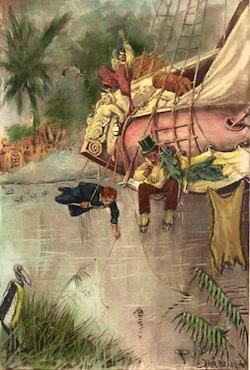

The ship takes off, of course, with Huck and Jim and Tom all still aboard. They soon discover that it is piloted by a mad professor type who, like Tom, refuses to be outdone. The professor speeds east with them, refusing to stop before he gets to his next scheduled stop in London. Perhaps because he sees a kindred, glory seeking spirit, the Professor teaches Tom to operate the ship, and things are moving along swimmingly until they reach the Atlantic. In a stormy night over the ocean, the Professor has a fit of madness and, thinking the boys want to leave the ship (which of course they can’t do even if they wanted to), threatens to kill them. There’s a dramatic lightning-lit scuffle and the Professor winds up overboard. With rations to spare and nowhere in particular to be, the trio cruises over northern Africa, observing the landscape from the air and occasionally going down and interacting with the animals, the people, the famous architecture, and, of course, the many places named in the Bible. The trip ends once Tom’s corn cob pipe falls apart and he insists Jim drive the ship back to Missouri to bring him another one—Jim returns with the pipe, but also with note from Aunt Polly that insists that the fun is over and the boys had better return home.

The ship takes off, of course, with Huck and Jim and Tom all still aboard. They soon discover that it is piloted by a mad professor type who, like Tom, refuses to be outdone. The professor speeds east with them, refusing to stop before he gets to his next scheduled stop in London. Perhaps because he sees a kindred, glory seeking spirit, the Professor teaches Tom to operate the ship, and things are moving along swimmingly until they reach the Atlantic. In a stormy night over the ocean, the Professor has a fit of madness and, thinking the boys want to leave the ship (which of course they can’t do even if they wanted to), threatens to kill them. There’s a dramatic lightning-lit scuffle and the Professor winds up overboard. With rations to spare and nowhere in particular to be, the trio cruises over northern Africa, observing the landscape from the air and occasionally going down and interacting with the animals, the people, the famous architecture, and, of course, the many places named in the Bible. The trip ends once Tom’s corn cob pipe falls apart and he insists Jim drive the ship back to Missouri to bring him another one—Jim returns with the pipe, but also with note from Aunt Polly that insists that the fun is over and the boys had better return home.

This novel begins as a spoof of an adventure story much like those by Robert Louis Stevenson or Jules Verne, or any of the other adventure authors that Tom Sawyer allows to inform his well known, grandiose idea of reality. Petersburg’s competitive travelers are absurd, and the air ship is an unwieldy steampunk dream machine: it has hammered metal siding, wings that seem to do nothing, netting all over the place, a balloon that comes to a sharp point, and it can be operated by a twelve year old. (Some of these details aren’t described by Twain, but Dan Beard, on of Twain’s preferred illustrators, included those details in illustrations that Twain enthusiastically approved of).

Once the mad professor falls overboard, the parody falls off and the novel becomes a combination of two of Twain’s favorite things: travel writing (as best as Huck can manage it) and comedic dialogue between people with a very limited understanding of how the world works. The trio discuss whether time zones are a segregation issue, why it wouldn’t be practical to sell Saharan sand back home in the States (tariffs, Tom explains), and why a fleas, if human sized, would probably take over the railroads and the American government. If you love the absurd ways Tom, Huck, and Jim all manage to mangle basic logic, the long stretches of the book in which there isn’t much action will appeal to you, because talking is how they kill the time. These irrelevant dialogues are a nice opportunity to hang out, in a way, with the characters, and just allow them to talk; the other three late books (one finished, two incomplete), are action packed, and Tom and Huck don’t have a lot of time to shoot the breeze. Like almost every word Twain wrote, Tom Sawyer Abroad is a lot of fun to read, though the dialogue filled lulls between an adventure parody start and travel writing-esque conclusion do feel a little uneven. As great as it is, it’s easy to see why it didn’t maintain the popularity of its predecessors.

¹”School House Hill,” an incomplete novel that Twain wrote very late in life, is not narrated by Huckleberry Finn; however, this novel is about a polite and generous offspring of Satan coming from Hell to visit Petersburg, and Tom and Huck are merely peripheral characters. It’s one of the works that was adapted into The Mysterious Stranger.

Allegra Frazier is a writer, editor, and visual artist living in New York. She founded the Brooklyn-based literary magazine Soon Quarterly, and her work can be seen in The Brooklyner, in The Short Fiction Collective, Storychord, and elsewhere.