Horror and science fiction make great bedfellows. Both present us with monsters of mismatched body parts, sickening size, and/or unknown origins. Both deal with experimentation gone awry and the folly of mankind—the fatal mistakes of individuals mad with power or inflicted with a hubris they recognize all too late. Horror doesn’t necessarily have to be scientific in nature (and is often supernatural, beyond the explanations of science); likewise, science fiction doesn’t have to be scary in a cautionary sense. But when you fuse those elements together, you get a genre all its own—horror-sci-fi. And man, what a genre it is, particularly in the realm of movies. You’ll find some of the greatest examples of both horror and science fiction lingering in its confines—or, if you prefer to strip out all genre considerations, simply some of the best narrative fiction ever committed to film.

Let’s take a look at some of the hallmark titles of the horror-sci-fi genre. Of course, this list is in no way exhaustive, and many “lesser-known” movies will be sorely missed here (that’s why we have the comments section). Consider this more of a primer for the uninitiated, a starting place for anyone interested in traveling to the crossroads where horror and science fiction meet.

Ready? Then let’s do this. Here are ten fantastic, groundbreaking horror-sci-fi movies, presented in chronological order. Note that there will be some spoiler-ish moments throughout, and I’ll warn you ahead of time of these.

Frankenstein (1931)

In many ways, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the first sci-fi novel, the first modern horror novel, and the first horror-sci-fi novel ever written. Think about it—no other author prior to Shelly fused realistic, speculative science with prose fiction. Furthermore, even though horror was already around (horror will always be around), Frankenstein was a game-changer, as it brought a level of literary merit to the field, compelling other horror authors to flesh out their characters’ emotional arcs and narrative themes as well.

Since we’re talking about film, however, let’s go to perhaps the most iconic screen adaptation out there: Universal’s 1931 classic, directed by James Whale and starring Boris Karloff as the titular character’s monster (yes, the monster’s name is NOT Frankenstein). While not exactly the most faithful adaptation, it is famous for two reasons: one, the aforementioned Karloff, whose makeup and mannerisms inspired both terror and pathos in contemporary audiences (he plays the monster like a handicapped child); and two, for creating the “mad scientist” archetype in its depiction of Dr. Frankenstein, played by Colin Clive.

Like in the novel, the “good doctor” will go to all kinds of loony lengths (grave robbing, for instance) to realize his experiments in reanimation, and he’s isolated himself from the people who love him. Unlike the book, Frankenstein conducts his experiments in a gothic castle high up on a hill and employs lightning and beautiful, space-agey machinery (including, reportedly, Tesla coils designed by the man himself) to bring his creation to life. When he finally succeeds, he spins around and declares, “It’s alive! It’s alive…! Oh, in the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!” This line and its maniacal delivery inspired countless crazed scientists for decades to come. Yes, James Whale’s film does owe a lot to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, specifically Dr. Rotwang and his laboratory, but I think Frankenstein more than any other film brought the mad scientist into popular consciousness.

As terrifying as the doctor’s God complex and his resulting madness is, the film culls its true scares from the villagers living on ground-level below the castle. They see only the monster’s towering height, sloping brow, scars and dazed eyes; they’re too busy screaming and raising torches and pitchforks to see the lost, helpless soul underneath his ghastly appearance. He only becomes violent when threatened, and kills only one innocent person by pure accident; the villagers, however, react as though the monster were a mindless, marauding killer. Ultimately, the horror in Whale’s Frankensteinis overreaction and hive-minded brutishness. One need only read the current headlines to understand that an impromptu mob is truly a deadly thing.

Gojira (1954)

Like Frankenstein, Gojira—or, as we know the big guy here in America, Godzilla—isn’t necessarily a “scary” movie anymore. In many ways, the stop-motion effects, puppetry, and costuming employed to bring the monster to life are dated. But there are three key reasons I’m including this film on the list: one, Godzilla is awesome, so deal with it; two, Gojira fathered an entire sub-category of horror-sci-fi, the mutated-giant-monster destroys-civilization-movie—or kaiju films, as they’re known in Japan; and three, neither the plentiful sequels to come nor the countless knock-offs produced in Japan, the UK, and America could ever top the pure visceral terror accomplished by writer-director Ishirô Honda and fellow writers Shigeru Kayama and Takeo Murata. Many of the films that followed were quite campy and cheesy, but if you look past the dated special effects of Gojiria, you’ll see less of a run-of-the-mill mutated monster run amok, more of a vengeful demon punishing mankind for disrespecting nature. Look at Gojira’s eerily glowing eyes and the expression of crazed glee he wears on his face as he stomps, tramples, and burns Tokyo to a crisp, and you’ll understand why the original is still the best.

But make no mistake, as horrific as Gojira is, humans and their infinite quest to build bigger, better, more destructive weapons are far worse. It is this quest for destruction that creates the monster in the first place (he’s awoken from deep sea slumber by nuclear bomb tests), and the only thing that can destroy this menace is a weapon of such unimaginable force and ruination that its inventor, Dr. Serizawa, refuses to use it.

In this way, Gojira poses many of the same questions as Frankenstien: science can take us to wonderful heights of discovery; but should we take such flights into the unknown? And if we do, what are the consequences?

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

This movie is less about an alien race that repopulates earth with “pod people”—replicants with evil intentions that look, sound and act just like your friends and family—and more of a thinly-veiled commentary on the “red menace” skulking its way from Russia to your idyllic doorstep (or, a critique of the increasingly homogenized facelessness of American suburbia, depending on who you ask).

In any case, Invasion of the Body Snatchers plays into some of our most basic fears. The idea that the person you know and understand to be yourself could be stripped down to a cold, uncaring facsimile—that your thoughts, emotions and basic identity are so easily expendable—is a terrifying one, to be sure. More shiver-inducing than this, however, is the idea that the same thing could happen to a loved one, and you’d have no way of knowing for sure; that this thing, this impostor, could sit right next to you without your knowledge.

The film also taps into our fear of isolation, particularly in the context of a culture obsessed with “rugged individualism.” For Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy), running for his life in a town infested with “them” is the most horrifying experience of his life. He is the lone voice of reason, the one sane man in a world gone crazy, the only guy who can stop the invading evil. The problem is, the harder he fights and the longer he runs, the more insane he becomes, to the point where he’s screaming in the middle of the street at passing cars, warning the drivers and passengers, “They’re here already! You’re next! You’re next! You’re next!” All the while, his antagonists are perfectly calm, cool, and collected.

Paranoia was a big theme in the 1950s, for the sheer fact there was a lot of it going around. Body Snatchers addresses the paranoia arising from external forces—can you trust your neighbor?—but its real appeal comes from an examination of the paranoia within—can I trust my own mind?

Fiend Without A Face (1958)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This “lost classic” isn’t so lost anymore thanks to a spiffy rerelease from Criterion. We have here just about every element a good 1950s horror-sci-fi film should have: cold war paranoia a-la Invasion of the Body Snatchers, nuclear paranoia a-la Gojira, and a nasty monster that terrorizes the characters a-la, well, every good 1950s horror-sci-fi film.

But this is no run-of-the-mill B-movie. Based on “The Thought Monster” by Amelia Reynolds Long, Fiend is a different kind of animal. First, the fear of communist take-over is a mere plot device—it’s the reason an American army outfit has set up camp in Canada. They’re testing an experimental radar system that can spy all the way into Russia, but it requires a hefty dose of nuclear power to maintain. Here’s where nuclear paranoia comes into play, though it’s a fear of fallout rather than the A-bomb, as the rural citizens of the small Canadian town are nervous about the power plant and the presence of the Americans in general.

The horror begins when an invisible killer—the titular fiend—begins inexplicably knocking off villagers. Some believe the army is to blame, while others are convinced it’s merely a madman loose in the woods. Regardless of the source, the torches and pitchforks are raised, and a monster hunt ensues. Here, screenwriter Herbert J. Leder and directer Arthur Crabtree are not only visually referencing the Universal monster films—Frankenstein in particular—but they’re also implementing the Val Lewton principle of filmmaking: the less the audience sees, the scarier the monster is. So when the invisible killer strangles its victims, we see nothing more than a bunch of actors grasping at their throats and screaming in pain and terror. Fortunately, the acting is convincing here, with some pretty horrific death faces plastered across the screen in close-up.

The filmmakers do eventually let us see the monsters, however, but not before offering one of the most outlandish and awesome origin stories ever captured to film. The fiends emerged from (SPOILER!) the “thought materialization” experiments of one Professor Walgate, our resident mad scientist in the film. He literally thinks these “mental vampires” into existence by strapping himself up to some equipment that feeds off the army’s nuclear power plant, thus giving us a slight twist on the radiation-as-monster-maker trope seen in countless contemporary films. This origin story also takes Lewton’s theory of the imagination as the ultimate monster-maker to its literal conclusion. Heady stuff for a cheapie picture, no?

When the creatures manage to turn up the plant’s wattage and fully materialize, we find out these things are floating brains with spinal chord tails and spindly legs. Being visible means they’re also super killable, and that’s exactly what the army men set about doing. What follows is an extended, stop-motion creature gore fest that would make George Romero and John Carpenter proud (but more on Carpenter in a bit…). Note that this is 1958, i.e., a time when blood and guts weren’t exactly prevalent on movie screens, making Fiend Without A Face a kind of schlock horror pioneer.

Nasty fun aside, this movie does address serious concerns about military encroachment on rural territories and the dangers of nuclear power, while giving us a wholly original explanation of the monster’s origins. Just forgive the film for its ham-fisted love story and misogyny (we are dealing with the 1950s, after all).

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Okay—sci-fi, clearly. But horror? I mean, Stanley Kubrick’s lone foray into the horror genre was 1980’s The Shining, right?

Yes and no. While eighty to ninety percent of 2001 is straight-up science fiction, that other ten to twenty percent is most definitely horror. Let’s face it, people: HAL 9000 is freakin’ terrifying, not only for its representation of a terrifying idea (that artificial intelligence could become unintentionally murderous given the right directives) but its execution. HAL is a round red light and a dulcet, monotone voice, but its so much more than that. Its everywhere in the ship. It sees all. It knows all. It’s cold, calculating AI that cares only about its mission. It’s smart enough to read lips, and it’s definitely smarter than you. HAL has one Achilles’s heel, but you have to get to it first.

Rewatch the HAL segments of 2001, and compare the ways Kubrick mounts tension (and terror) in this film and in The Shining. You’ll see it. If HAL doesn’t scare you, you might be a robot too.

Alien (1979)

If you’re talking horror-sci-fi, you have to talk about Alien. While it isn’t the first entry in this hybrid genre, in many ways it’s the quintessential title. Alien not only presents us with a scary monster and ideas that are horrific, but director Ridley Scott and writers Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon actively play with the language of horror, from the shocks and stings emerging from the narrative, to the shadowy, less-is-more lighting and atmospheric sound design. And the film is every bit as indebted to B-movie space alien narratives as it is to The Exorcist.

In this day and age, we’re culturally familiar with face-huggers, chest-bursters, and xenomorphs (three incarnations of the same alien), even if we’ve never seen any of the films in the series. We just grow up knowing what these things are. Same with Freddy Kruger, Ronald McDonald and Homer Simpson. Because of this, we tend to forget the sheer groundbreaking magnitude of H.R. Giger’s alien design. This was a monster the likes of which we’d never seen before (and in a lot of ways, ever again). The creature was certainly something from a nightmare, an amalgamation of reptilian and insect origins, with a little peppering of human DNA for good, horrific measure. It’s a fast-moving, ruthless animal that seems to live only to stalk and kill other organisms. Truly wonderful stuff.

As original as the creature is, however, Alien also borrows heavily from several of the aforementioned films: the pods discovered by Kane (John Hurt) reference Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and the face-huggers are reminiscent of Fiend Without A Face. But perhaps the most significant nods are throwbacks to 2001 and Gojira. In the case of the former, not only does the look and feel of the starfrieghter Nostromo resemble Discovery One, but we also have the presence of (SPOILER!) Ash, the android spy sent by the unnamed “corporation,” and Mother, the computerized ship “commander” whose primary objective is to find, capture and deliver a dangerous alien specimen for further study—an objective “she” and Ash will kill to accomplish. HAL 9000 all over again.

It is also this objective that leads to Alien’s association with Gojira—Ripley theorizes that the “corporation” wants the alien for its weapons division. This appetite for destruction, as it were, tops Gojira in terms of terror because the “corporation” is nameless and faceless, a cold entity out there somewhere with no regard to human life. Ash summarizes this lust quite eloquently. Speaking of the alien, he says, “You still don’t understand what you’re dealing with, do you? Perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility…I admire its purity. A survivor…unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

Remember, this film was released at the cusp of the 1980s, when private corporations and the military industrial complex were enjoying a lovely honeymoon. Given that corporations now have the same rights as individuals, Alien’s corporation seems all the more prescient and horrifying.

The Thing (1982)

John Carpenter’s most ambitious and, arguably, best film is another example of filmmakers paying homage to the horror-sci-fi classics that came before it. And no, I don’t simply say this because the movie is a remake of The Thing From Another World, though it is important. Like Body Snatchers, Alien and its source material, The Thing deals with an entity of unknown origin—something remote, foreign, and unrecognizable to human eyes. In the original film the creature has its own unique look, but Carpenter makes his creature totally formless. He borrows the shape-shifting notion seen in Body Snatchers, but he takes it one step further by making his creature capable of transforming into any living organism, any time it wants, thus upping the paranoia ante about a hundred-fold. I mean, this “thing” can shape-shift into a dog, for crying out loud!

The characters—Kurt Russell’s MacReady the most prominent—quickly realize that no one can be trusted, and the menace known as “human fear” quickly emerges. It’s a classic tale of monsters breeding more monsters breeding more monsters, and from a narrative standpoint it’s one hell of a ride (if a tad morose at times).

But there’s one element to The Thing that really brings audiences back time and again, despite the passage of time and release of “reimaginings”—the special effects. People, this movie came out in 1982, but the many, thoroughly nasty incarnations of the Thing never fail to amaze. When one character’s head separates from his body, grows legs and begins scurrying around the floor, another man says, “You gotta be f*ckin’ kidding.” That’s us! We’re the ones saying that as we watch this…I mean, that dude’s head just grew legs and walked around the floor! Yes, we’re terrified at the dark depths human beings will go to to survive. Yes, we’re horrified by the idea of a creature that can be anything and anyone (and, when set loose in a remote station in Antarctica, we feel claustrophobic and trapped); but at the end of the day, we’re thrilled by our terror, because we’re in utter awe at the way the special effects team brought this Thing to life.

The Fly (1986)

David Cronenberg is the king of horror-sci-fi. His body of work (pun intended: Cronenberg’s films are also called “body horror”) include Rapid, The Brood, Scanners, Videodrome, and eXistenz. So why talk about perhaps his most famous film, The Fly, a remake of the 1958 B-movie starring Vincent Price? Simple: it’s the most straight-forward horror-sci-fi film he’s ever made.

In many ways, Cronenberg’s oeuvre exists in a category all its own. The director straddles the lines not only between horror and science fiction, but also bizarro fiction, psychological thriller, dramatic character study, and full-blown tragedy. I included Videodrome as an example of his horror-sci-fi work, but really, that movie’s actual genre is hard to pinpoint, except to simply label it a “Cronenberg film.”

Now, I’m not saying The Fly isn’t original. It bears no resemblance to its cheesy (and fun!) source material. Instead of science run amok, Cronenberg’s The Fly deals with the pitfalls of human emotion in relation to scientific exploration. Jeff Goldblum plays Seth Brundle, an awkward and lonely scientist who, through careless experimentation with his teleportation device, accidentally fuses his DNA with that of a common housefly.

The key to this story, however, is not the slow (and, at times, disgusting) transformation Brundle undergoes throughout the course of the film, but the quick changes in character we witness prior to his botched self-teleportation. It’s clear Brundle is awkward and a bit lonely when he picks up Veronica (Geena Davis) at a science convention. As their relationship intensifies, we see Brundle become co-dependent and illogically jealous. After he becomes half-man, half-fly, the monster is released—though this was a monster long-dormant inside Brundle already. True to the genre, the terror in The Fly isn’t science per se, or physical deformation/dismemberment, but the folly of man. It’s a heavy but ultimately important message. Definitely not for popcorn munchers or the squeamish.

Hardware (1990)

We’re getting back around to evil AI with this one, but in a way you’ve never seen before. This is by far one of the most original horror-sci-fi titles on the list, and it’s hands-down one of my favorite movies of all time.

Now, this isn’t to say Hardware is a fun movie, per se, as it takes place in a horribly bleak post-apocalyptic world. It features a self-repairing android skull, the MARK 13, which was (SPOILER!) manufactured by the government to wipe out humanity. Part home-invasion narrative, part HAL 9000/Demon Seed throwback, part Terminator knock-off (I use the word lovingly here), part The Thing-level shock-fest, and part seeming existential study on humanity’s survival instincts despite the inevitability of its extinction, this movie has it all.

But there’s one aspect of this film that heretofore the others haven’t exactly demonstrated: for all it’s science fiction, for all its horror, for all it’s special effects and rock star cameos (Iggy Pop, Lemmy Kilmister, Carl McCoy), at the end of the day, Hardware is an art film. It doesn’t have much of a plot (it’s really about the characters, in the end), and my God, it is visually stunning. You could watch the last thirty minutes of this film with the sound turned down and still be just as enthralled. Seriously, I can’t say enough good things about Hardware. As of this writing it’s available on Netflix Instant Watch, so just go do it. I’ll wait…

Cube (1997)

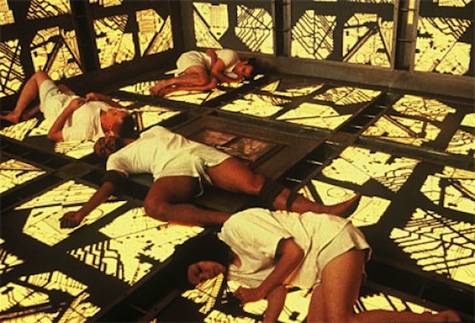

Visually, this 1997 Canadian indie owes a debt of gratitude to 2001. The look of the titular cube—a totally unexplained series of interconnected square rooms that randomly imprisons innocent people—recalls the famous destruction of HAL in Kubrick’s film. Each room features a kaleidoscope of saturated blues, greens, oranges, reds and stark whites.

Though the six strangers have no idea why or how they ended up in the cube, they share a common goal in getting out. Unfortunately, many of the rooms are fatally booby trapped. At first, the characters try to cull their individual strengths and escape as a team, with mathematics student Leaven cracking the numbers labelled outside each hatch door, a guide for dodging decapitation wires and sprinklers rigged with acid.

I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to say that not everyone makes it out alive. But the gory bits in Cube aren’t what tip the film over into the horror genre. While the visuals and the tech might be Kubrick, the plot is all Romero, specifically Night of the Living Dead (Alien and The Thing both have a little of their DNA in there too). As the isolated characters grow more fearful—moving from one identical, claustrophobic space to another, unsure if death is around the next corner—they quickly slip into paranoia and mistrust, revealing the darker shades of humanity. As Rennes, the professional prison escape artist warns, “You’ve gotta save yourselves from yourselves.”

From a macroscopic view, this movie asserts that humanity, in order to survive, must work together to solve its problems; if we can’t do this, we’re never going to make it out alive.

So why does my list end at Cube, which was released sixteen years ago? Were there no prominent titles released since then? Well, in part, the issue is personal—I simply haven’t seen some of the more recent films belonging to the horror-sci-fi genre. But the other side of the coin is, even if I have seen them, I don’t really consider them eligible candidates. For instance, some argue that 28 Days Later is a cross between horror and science fiction. I just don’t see it—I mean, yes, the “zombies” in that film are created from a virus, but there’s very little talk about the science behind the virus, or how to find a cure. Rather, this is a film about everyday people trying to survive the apocalypse, and the horrible things other humans will do to each other in the name of survival. No sci-fi there. Same with Resident Evil and World War Z. I guess for me, zombies will always be straight-up horror, regardless of any science-based origins. Event Horizon almost made the cut, but I left it out simply because much of its horror stems from supernatural elements, rather than science.

So I’ll turn it over to you, dear reader. What horror-sci-fi movies would you put on this list. What about some of the earlier films in the genre? Shout ‘em out in the comments below!

Christopher Shultz writes all sorts of things—fiction, columns, tweets, you name it. He’s a regular contributor over at LitReactor. He lives in Oklahoma City with his partner Lauren and their two cats.