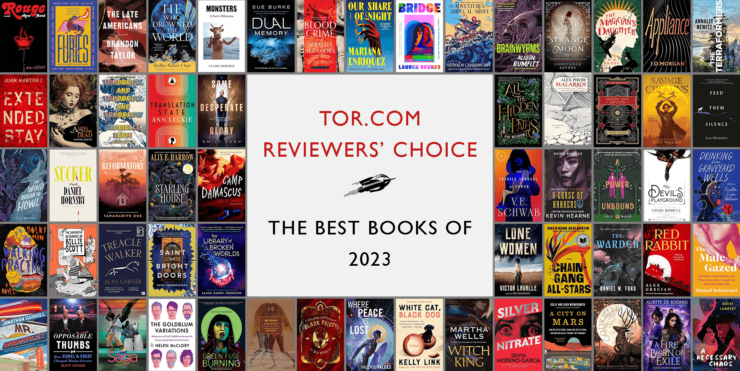

It’s been a very good year for reading. The book releases in the genres of science fiction, fantasy, young adult, and beyond took us to faraway kingdoms, beyond the stars, into haunted houses, and even back in time—and we are so lucky to get to read them all. Our reviewers each picked their top contenders for the best books of the year, which feature spooky trips across the American West, swoony romantic entanglements, brutal dystopian futures, new gods, old gods, A.I.s, and family curses. We’ve got magic, mystery, adventure, and much more.

Below, Tor.com’s regular book reviewers talk about notable titles they read in 2023—leave your own additions in the comments!

2023, for me at least, was the year of reading books that center around some sinister and/or supernatural happenings around an old film. There’s Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Silver Nitrate, of course, which is deservedly on many “best of” lists because of its strongly developed protagonists and its harrowing portrayal of a Nazi occultist looking to live forever via a presumably destroyed film. But then there’s also The Star and the Strange Moon by Constance Sayers and The Devil’s Playground by Craig Russell, two books that feature mysterious films that may or may not be cursed. And while the structure of these two is superficially similar—both unfold over two separate timelines—The Devil’s Playground veers into our thriller/horror territory while The Star and the Strange Moon is more fantastical, and with a much happier ending.

On the epic fantasy front, perhaps the book I was most excited about was The Fragile Threads of Power by V.E. Schwab. I’m a big fan of the first trilogy set in the overlapping Londons, and the first book in her new series met my high expectations. I can’t wait for the next installment. I also read the entire Savage Rebellion trilogy by Matt Wallace this year, with the third book, Savage Crowns, arriving in the summer. The series includes some phenomenal characters in addition to the one that graces the cover of each book in the series, and has an engagingly crafted world.

Last but not least, I also really enjoyed The Magician’s Daughter by H.G. Parry, a historical fantasy that contains rich worldbuilding and fully developed characters. It’s a book I got lost in this year, and one of the few I’ll likely read again.

–Vanessa Armstrong

When I was picking my favorite books for this year, I thought they had nothing to do with each other: a fantastical Western, a thriller about a how-to murder school, a deep and skeptical look at the practicality of space settlement. Then I realized that their uniting factor is that all are deeply ambitious books, with scopes that could be overwhelming in scale—yet the authors manage to drill down into the ways that individual actions matter, the ways that they can meaningfully shape these larger stories.

First up is Alex Grecian’s Red Rabbit (the fantasy Western). It’s the story of an impromptu posse out to kill a witch in Kansas. It’s also the story of that witch, and a sheriff’s deputy, and a widower, and an outlaw, and a hunter, and a shopkeeper, and a dozen more besides. It’s a bloody, atmospheric, enthralling story in which Grecian demonstrates his skill in sketching out rich, real characters in just a few paragraphs. I picked it up hardly knowing anything about what I was getting into, and it only took a chapter or two before I found I couldn’t put it down.

Next is Rupert Holmes’ Murder Your Employer (the how-to murder school). It’s a cathartic book, about three students who have ethical, justified reasons for “deleting” someone who is making their lives hell. This has been determined by the McMasters Conservatory for the Applied Arts, who gives each of them the tools and training to delete their targets effectively and get away with it. But it’s also just a fun book, like a reverse murder mystery where the joy is in seeing how this complex plan all comes together.

Finally, in nonfiction, was Kelly and Zach Weinersmith’s A City on Mars (the space settlement book). The last couple of years have seen a resurgence in broad, optimistic claims that humanity can and should set out to settle the Solar System as soon as possible, often with overly generous or poorly researched claims. The Weinersmiths’ book takes a hard look at whether we really understand zero-G biology, ecology, and policy, and finds that in many cases we don’t. It’s a sobering book, but also, ultimately, a hopeful one—and perhaps recommended reading for lots of sci-fi fans out there.

–Charles Bonkowsky

This year contained a plethora of excellent books. I’m sure other writers will talk about Ann Leckie’s Translation State, or Martha Wells’ Witch King and System Collapse, outstanding examples of those authors’ works. So let me focus on less well-known contenders.

Valerie Valdes’ Where Peace Is Lost is my favourite novel of the year. It’s a well-executed, rip-roaringly good planetary space opera adventure with an incredibly skilled warrior protagonist—a protagonist whose commitment to the cause of least harm involves a willingness to die rather than kill, because her enemies’ lives are also valuable. A refreshing and entertaining look at the ethical conundrum of armed pacifism.

Daniel M. Ford’s The Warden is great sword-and-sorcery fun. Hotshot necromancer graduate of magic college gets prestigious position in government service—serving a village in the arse-end of nowhere. Surely nothing can go more wrong than her leaky tower roof and the sheep in her living area? She soon discovers boredom is underrated. Queer, quirky, and very enjoyable.

Hannah Kaner’s Godkiller is a fantastic debut. Gods, like rats, can be dangerous. Sometimes—often—they need killing. But when your local god-exterminator runs into a cute kid with a god (and a conspiracy) problem, shenanigans ensue. And a road-trip. A Fire Born of Exile, the latest romantic outing from Aliette de Bodard in her Xuya space opera continuity, is a wonderful take on The Count of Monte Cristo. Secrets, revenge, concealed identities, riots, and exactly the wrong time to be falling in love: It has it all. While Foz Meadows’ All the Hidden Paths is another delightful fantasy adventure of romance and intrigue. So you’ve made an arranged marriage to seal peace between nations—but to the young lord rather than the young lady. Not everyone’s as happy as you are. Now what?

I could go on (Barbara Hambly’s return to epic fantasy in The Iron Princess, Melissa Scott’s new space opera The Fallen) but I think I’ve already overshot the wordcount here…

–Liz Bourke

There are so many books I want to shout at you about, but I’ll contain myself to the following four titles. Stelliform Press described Tiffany Morris’ Green Fuse Burning as “transformative Indigenous eco-horror novella,” and they weren’t kidding. This story is about a queer Mi’kmaq artist who isolates in a cabin to reconnect with her work and roots and is slowly consumed by thoughts of death and dread. It’s surreal and poetic, unsettling and compelling.

Of course Victor LaValle’s Lone Women was going to make my list. The first draft of my massive review/essay tordotcom graciously posted was over 5,000 words long because there’s just so much to talk about! LaValle vividly, brilliantly, imaginatively combines history with horror, highlighting a region and perspectives that are often ignored. I can’t wait to reread this.

A Necessary Chaos by Brent Lambert might not be on most people’s radar, but this futuristic SF novella is a must read. If you liked How to Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone, then you’ll love this. Fantasy, science fiction, and dystopian all blend together into this queer romance that is fiercely anti-imperial.

I am obsessed with Witch King by Martha Wells. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about it. Kai, the morally gray, resurrected demon, and his merry band of witches, survivors, and warriors traverse a fantastical realm recovering after being nearly destroyed by an invading empire. There’s a murder mystery, political intrigue, and a meditation on the cost of colonization. The world is lush and creative, and the characters are fascinating and unique.

For short fiction, kudos to “How to Raise a Kraken in Your Bathtub” by P. Djèlí Clark, “A Witch’s Transition in the City of Ghosts” by Oluwatomiwa Ajeigbe, “The Ghost Peach Pet Rescue” by Eden Royce, “The Cursing of Herman Willem Daendels” by A. W. Prihandita, and “Negative Theology of the Child from ‘The King of Tars’” by Sonia Sulaiman. I read a lot of tremendous short speculative fiction this year, but these are the ones that I just can’t seem to let go of.

If you’re wondering where my young adult recs are, I’ve decided to save them for my Most Notable YA list. Keep your eyes peeled for that 2023 wrap-up coming soon. I’ll leave you with a teaser of Tim Te Maro and the Subterranean Heartsick Blues by H.S. Valley and Harvest House by Cynthia Leitich Smith.

–Alex Brown

You’re seeing Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah everywhere, its razor-sharp and fiery cover, for a good goddamn reason: It is simply one of the best books I’ve read in the last decade. Its fury, its heart, its splendor and condemnation, when coupled with the empathy, love, and fellowship that Adjei-Brenyah invokes as remedy to the countless brutal systems humanity has both created and trapped each other in, will make this a foundational text of capital-L literature for many, many years to come. Friends, it really doesn’t get better than this.

One of the first books I read this year and reviewed, The Terraformers by Annalee Newitz kept a grip on me for all of 2023. Newitz balances the epic and the intimate, telescoping from one to the other with envious ease, employing the passage of time to illustrate, on multiple levels, how a planet is born, but a world is created. Through three generations, Newitz uses the terraforming project of planet Sask-E to showcase and explore ideas of community, sapience, sentience, justice, gender, sex, and more, while also having a blast showing us these generations through the eyes of peoples of all kinds, not just bipedal humanoids but also flying moose, earthworms, and yes, a train.

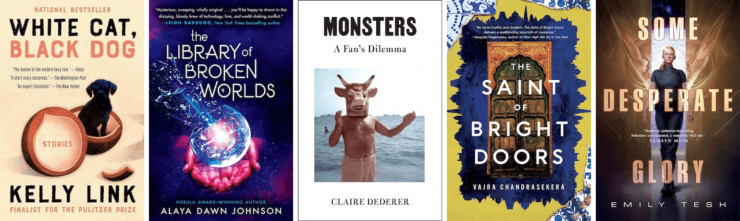

The latest collection from a fabulous fabulist, this titan of short tales, White Cat, Black Dog showcases Kelly Link at her very best, and is a wonderful introduction to her work. Each story begins as the seed of a fable from our narrative past, one which Link infuses with her very own brand of love, oddity, horror, humor, and dark playfulness, making it something wholly unique. Reading these stories filled a well in my heart I didn’t know had run dry, and I hope you’ll find them just as fulfilling. (Spoilers: You’re going to see Link’s novel The Book of Love on my list next year, I promise; I’m calling my shot now).

Once again, I flail hopelessly at just picking three top reads in a year chock full of beautiful, transcendent work, so in addition to those above, I’m also shouting out Chana Porter’s absolutely delicious The Thick and The Lean, Victor LaValle’s haunting and sharp Lone Women, the thorns and blooms of Roshani Chokshi’s The Last Tale of the Flower Bride, the sleek, enthralling magic of Brent Lambert’s A Necessary Chaos, and the blood and snow of Cassandra Khaw’s The Salt Grows Heavy. In addition, short fiction continued to be both balm and blade in trying times, my heart pried open and healed by the works of Suzan Palumbo, Eugenia Triantafyllou, John Wiswell, Nino Cipri, Theodora Ward, Ai Jiang, Lyndise Manusos, L. D. Lewis, Isabel J. Kim, and many more.

–Marty Cahill

You don’t need uncanny moments or supernatural beings to summon up a sense of horror these days; a glimpse in the newspaper or into a history book will often do the trick. Still, there’s a long tradition of juxtaposing historical horrors with paranormal ones, like Sebastià Alzamora’s Blood Crime, about a vampire making his way through the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War.

This year brought two notable examples of that juxtaposition, with Mariana Enriquez’s Our Share of Night (translated by Megan McDowell) and Tananarive Due’s The Reformatory both standing out for a few reasons. They’re both books grounded in familial experiences, set against a starkly-rendered historical background; Due’s reckoning with the Jim Crow South and Enriquez’s evocation of Argentina’s Dirty War are gripping enough even before the supernatural elements come into play.

Juan Martinez’s Extended Stay doesn’t reckon with real-life history, but it does feel decidedly current in its tale of a hotel near Las Vegas that’s become a waystation for people on society’s margins—and is also alive and hungry. And Laird Barron’s The Wind Began to Howl takes his crime fiction protagonist Isaiah Coleridge into more surreal territory, as he tracks a missing musician who may be connected to a hallucinatory government project. The resulting work is haunting on both a rational and a dreamlike level.

–Tobias Carroll

Yvette Lisa Ndlovu’s Drinking From Graveyard Wells is a force of a debut. An acclaimed Zimbabwean sarungano, she delivers a short story collection that positions her unequivocally as a commanding voice in this space. Absolutely a writer to watch.

Lee Mandelo’s Feed them Silence packs so much excellence into a taut novella it left me breathless: a wild and brilliant premise executed to devastating perfection. A brutal excavation of research ethics in the face of evolving tech—monstrosity, dissociation, duty in a dying world, and complex queer appetites.

Some Desperate Glory is the queer, anti-war, thoroughly imagined answer to Ender’s Game I never knew I could hope for. It gets at the complex work of what it means to unlearn a colonialist militia mindset—deprogramming and rebuilding, on both personal and systemic levels. It’s wildly fun, brutally real, and so cathartic to read I laughed aloud with joy at some of the moments of biggest impact. One of my favorites of the genre.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia stuns again with Silver Nitrate. A sleek, cinematic magic system, a shitty Nazi exploiter, and bisexual disaster best friends uniquely equipped to take him down. A real delight to read.

It’s hard to nail a series ending, but Freya Marske does it in A Power Unbound and I’m so grateful. She knows what we want! Found family magic, a finale that hits hard while breaking only what needs to break, and some of the kinkiest, most romantic sex in the series. I saved the last few chapters for when I needed a pick-me-up because I knew they’d fix me and also I didn’t want the series to be over. It worked—they did—and Freya’s since announced a new book!

Grateful for the magic so many writers brought to the page this year. Looking forward to what’s to come.

—Maya Gittelman

My 2023 was busier than I would have liked, and so I didn’t have the chance to read or review half as much as I would have liked. Ed Park’s Same Bed Different Dreams and Adam Roberts’ The Death of Sir Martin Malprelate, to take just two examples, might have made my list if only I’d had a little more reading time.

Jonathan Carroll’s Mr. Breakfast was the first book I reviewed this year and remains a favorite. Generous, unpredictable, funny, and occasionally harrowing, it’s a perfect introduction to a major fantasist.

Sue Burke’s Dual Memory was a satisfying thriller about art, climate, conspicuous consumption, and artificial intelligence. Burke remains one of our foremost science fiction writers.

Alan Garner’s Treacle Walker, finally released in the United States a year after its British publication, is a slim and powerful novel of memory, mortality, and landscape. Though it stands entirely on its own, it gains new resonances if read with other Garner books, particularly his 2018 memoir Where Shall We Run To?

Finally, Lisa Tuttle’s My Death, reissued in October, is a perfect uncanny novella about two writers and their blurring identities. It’s not conventionally scary, but it will haunt you.

–Matt Keeley

Walking Practice by Dolki Min (translated by Victoria Caudle) remains my favorite novel for the year, for the same reason I wrote back in my Queering SFF Pride Month piece: It absolutely rang my brain like a bell. Walking Practice forwards a dynamic, unsettling, and electrifying vision for what queer artists can still do within speculative fiction.

Next up, I adored two new books from familiar voices, Starling House by Alix E. Harrow (“what if Hill House wanted to be your friend?” meets Appalachian gothic romance) and He Who Drowned the World by Shelley Parker-Chan (the sequel to She Who Became the Sun which continues its expertly agonizing explorations of queer masculinity, empire-building, and hunger). From the literary-but-relevant-to-sf-readers end of things, I must recommend Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow because it knocked my goddamn socks off—I haven’t wept that hard reading a novel in a while. As for one lil’ taste of nonfiction, I’d recommend The Male Gazed: On Hunks, Heartthrobs, and What Pop Culture Taught Me About (Desiring) Men by Manuel Bellancourt

(Lastly, I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t sneak in at least a mention of my other favorite novel this year, which was The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor. He never disappoints!)

–Lee Mandelo

The first on my list is Lauren Beukes’ latest thriller Bridge, a story of mothers, daughters and grief. It’s about a young woman who finds a strange object in her dead mother’s things, an object she thought she imagined, a ‘dreamworm’ that allows her to travel between worlds. And travel she does, with the sole purpose of finding her mother, who she is convinced is still alive in an alternate universe. Like with Beukes’ earlier novels, this too is a clever puzzle box thriller, capturing the zeitgeist of the moment. It’s also a really poignant look at love and grief, and how to survive both.

Rouge by Mona Awad is another—though vastly different—story of the fraught bond between a mother and daughter. It’s a strange, tense story about a young woman who is attempting to come to terms with her mother’s sudden death, and in doing so, trying to understand what had been happening in her mother’s life in the last few years when they had drifted apart. Belle finds herself drawn to the strange beauty spa her mother had been caught up in, and in Belle’s own fixation with skin care, Awad just drowns us in a luxurious gothic-feeling fever dream about the cult of youth and beauty. But as with Beukes’ book, Rouge also harbours a dark heart that pulses with grief and loss.

And then there was Furies: Stories of the Wicked, Wild, Untamed, a fun collection of shorts from feminist publisher Virago to celebrate their birthday. Each story is named for a word women have been called over the years, women who challenged society, spoke up, stepped over some imagined line set up by the patriarchy. Dragon, hussy, siren, wench, churail, tygress, fury, termagant—they’re all here, in a series of stories from fifteen writers who take back the power in every word used to belittle or vilify a woman. The writers are from all over, their stories representing different genres, times, places in the world, cultures, and they are all just excellent writers with their own unique voices. Margaret Atwood, Kamila Shamsie, Helen Oyeyemi, Kirsty Logan, Ali Smith, Calire Kohda are some of the writers included in this smart, poignant collection that covers everything from generational trauma, to women’s rights, migration, menopause and sexual identity.

–Mahvesh Murad

Malarkoi by Alex Pheby is dense, grim, and at times downright cruel, but it’s such a rich vein of arcane fantasy that a particularly dedicated reader could (pointlessly) mine it for meaning, forever. It’s an extraordinary world that follows its own opaque logic—a mad chaser to the Dickensian shot of Mordew that relied on familiar flavors of class and social order. Pheby is excellent at subtly telegraphing so many interstitial possibilities for his characters—so many things are possible, after all, if you can manipulate the Weft—and then throwing everything into perfect disarray before you get too comfortable. I’m dying for the third and final book, Waterblack, so that the trilogy can be examined as a whole.

Brainwyrms by Alison Rumfitt is easily the most viscerally upsetting book I’ve read in a while (perhaps since Sayaka Murata’s Earthlings, which is a rather different kind of existential nightmare), and also a transcendent piece of body horror and razor-sharp social commentary about fetish and trauma and survival. Rumfitt will rub your face in the hot, fetid guts of a sick, rotting England until you come out through the other side with clear eyes and a new purpose.

–Alexis Ong

Let’s begin with vampires two ways! Samara Breger’s A Long Time Dead is, I think, the perfect read for anyone who’s hooked on Rolin Jones’ Interview with the Vampire update. Instead of Louis and Lestat’s toxic love, we have the bumpy, thorny, twisty, complicated relationship between Poppy, a newly-turned sex worker who’s trying to figure out how to create a new life in un-life, and Roisin, a startlingly Hozier-esque Irish vampire who’s trying SO HARD to tamp down her feelings for Poppy so she can focus on vengeance. The object of said vengeance? Her abusive ex, Cane… the ancient, extremely powerful vampire who turned Poppy to taunt her old partner. But if you prefer your vampires a bit more sleek and modern, you can sink your teeth into Sucker by Dan Hornsby. Sucker starts out as a note-perfect satire on Silicon Valley, with our scruffy protagonist, Chuck Gross, the scion of an evil, powerful family whose current rebellion consists of running an indie label under a fake name. When Dad threatens to cut Chuck off, he turns to Olivia Watts, his old Harvard classmate—whose own pet project involves immortality through chemistry. What starts as a fun survey of techbros and “disruptors” turns darker with each page, until Chuck finally has to confront some truths about his relationship with Olivia… and his relationship to reality as he knows it.

Reading Opposable Thumbs might be the most pure literary fun I had this year. I read Matt Singer’s shared biography of Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert in a joyful rush over Thanksgiving. (I would say I give it two thumbs up but according to the book that would be copyright infringement???) Anyway, I loved it—this book kind of made me fall back in love with my job. Anyone with any interest in movie, criticism, or journalism should check this book out, and stick around for the end credits, where Singer rounds up some of the underappreciated films that Siskel & Ebert championed over their all-too-short time together.

Finally, Camp Damascus shocked me. I knew Chuck Tingle was a legitimately good writer. I knew he was a champion of weirdness and creativity and that he was all about PROVING LOVE. But I was still shocked by Camp Damascus. It’s a horror novel that goes to unsettling extremes without ever feeling gratuitous. It’s a heart-wrenching family story, and an uplifting found family story. It’s also hilarious in spots. Tingle has written a fantastic autistic main character whose autism is integral to her character, and not a “character trait” that’s tacked on or fetishized, or anything—it’s simply part of who she is. And of course, best of all as far as I’m concerned) the book handles religion with grace and sensitivity. The horrors of white supremacist misogynist homophobic christian nationalism are on full terrifying display, and some of the characters discard their faith as a result. But there are also characters who decide that their faith is stronger than the people perverting it—and Tingle, to his great credit, doesn’t pick a side.

–Leah Schnelbach

I love the eclectic mix of this annual article, and thought I’d lean in further. I’m not sure anyone needs another recommendation for, say Assistant to the Villain (40,137 Goodreads reviews). Instead, four books that may have slipped under your radar:

The Last Blade Priest by W.P. Wiles—The Kitschies’-winning fantasy that reads like K.J. Parker writing Joe Abercrombie. Maybe even better. An eldritch cult, an expansionist empire, a destiny to be fulfilled, and some truly disturbing elves. It is surprising and twist-y; clearly written with a deep love for the epic.

Appliance by J.O. Morgan—A throwback to the old-fashioned ‘stitch-up’ novel: interconnected SF shorts, exploring the invention, adoption, and adaptation of technology. (Matter transmission!) A bit like the above, this is an appreciative, imaginative approach to a classic format, packed with warm and thoughtful stories.

The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott by Zoe Thorogood—Thorogood’s debut graphic novel is ‘art about art’, which normally sends me running. But this is a heart-breaking, inspiring, and genuinely beautiful story about an artist who gets her breakthrough opportunity at the same time she learns she’s going blind. It is a personal, ironic apocalypse; how Billie copes makes for a powerful story.

The Goldblum Variations by Helen McClory—Another collection of nearly-flash-length fiction inspired by the greatest actor of a generation. This is a sassy, bonkers book with surprising depth, and shows that a great writer can write about, well, anything.

–Jared Shurin

First, a brilliant story collection from an all-time great: Kelly Link’s White Cat, Black Dog. Every time I talk to someone about this book, they have a different favorite story, and mine remains “Prince Hat Underground,” a story about love and quests and listening to snakes and not just staying home even when you’re middle-aged (or older). Among other things. This book is, like all Link’s collections, a joy and a wonder to read. How does she make it look so easy?

The latest YA novel from Alaya Dawn Johnson, The Library of Broken Worlds, is everything I could have wanted and more from the author of The Summer Prince. The inventiveness, the heart, the worldbuilding, the way she approaches violence, the role of friendship and family and the world in this story—everything I want in SFF storytelling is here, in an epic package that involves gods, planets, tesseracts, secret histories. And more. It’s a very big book, is the thing. A big heart and a big story.

One nonfiction book, because it’s relevant, I think, to everyone who reads and watches and considers and thinks about art and the people who make it: Monsters, by Claire Dederer, which tackles the question of whether one can (or should) separate the art from the artist, and beautifully comes down on neither side. There is no answer, but there is power in looking for it all the same, especially as wisely and thoughtfully (with a gimlet eye and a sense of humor) as Dederer does here.

Two debut novels I can’t get out of my head: Vajra Chandrasekera’s The Saint of Bright Doors, for which I will carry metaphorical pom-poms until the end of time. I did not expect a single thing that happened in this book, and at the same time, every single thing that happened made perfect sense in the world Chandrasekera created, full of cast-off chosen ones, crowdfunding messiahs, and unstable cities. And then, the book I read just in time to include: Some Desperate Glory by Emily Tesh, which presents a quote-unquote “unlikable character” and then lets her dig her way under the reader’s skin, despite her ego, despite her cruelty, despite her incredible misguidedness. Have I ever loved a brainwashed teen quite this much? Unlikely.

–Molly Templeton

The theme of my favorite 2023 reads this year I particularly liked leaned toward the fantasy side of SFF, perhaps in reaction to my all SF 2022.

Where Peace Is Lost by Valerie Valdes is Science Fiction, but with a character who is very much a Space Paladin, including wings and a kick-arse sword. The science fantasy result is indeed peanut butter and chocolate. And, her story of the last of her kind learning that she can’t escape her nature or her fate, and needs to step up again, is a timeless story for this moment.

Martha Wells’ Witch King has another character dragged into matters somewhat against their will. Along that way, however, we learn the long story of the titular demon, Kai, and we see just how Martha Wells’ longstanding skill in writing fantasy has not lost a single step in the age of Murderbot.

A Curse of Krakens by Kevin Hearne finishes up my favorite trio, and finishes his Seven Kennings trilogy at the very same time. The end of a three volume epic that is all about story and storytellers and the use of those tales in provide hope, and a chance for better worlds—even in the middle of an intercontinental conflict.

–Paul Weimer

Every year I think I’m choosing my favorite books in a vacuum, but in hindsight I always find touchpoints. Here it’s families and grief, not surprising as I’m growing mine around an absence that only becomes more pronounced with each new life change. But what I love is that each of these stories tackles those shared themes so differently, adorned and buoyed by SFF tropes.

Translation State, the latest standalone in Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch universe, boldly pushes back against what the Radchaai have established as universal gender and even personhood, building on debates raised by Ancillary Mercy and Provenance: If a station AI can be counted as a Significant Species, can the same be said for humanoids with seemingly “inhuman” genetics? More than that, it’s about the idiosyncrasies of families, whether clans or clades: Characters adopt new names through genetic quirks of fortune or by actually buying their way into a family tree, reuniting with new and old relations via vacations or treaty conclaves.

There’s an equally epic voyage at sea in Shannon Chakraborty’s delightfully swashbuckling The Adventures of Amina Al-Sirafi, which sees the eponymous retired pirate queen and mother called back to the waves to recover something greater than a treasure: a missing child. More than any other book this year, it’s just a trove of everything I could possibly want in one story: a dynamic found-family crew, a middle-aged protagonist who’s fearsome, and tender, magical sights and capers rooted in historical Islamic travelogues.

You know who I would love to see on the same crew? Amina and Alana from Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ space opera comic series Saga. Somehow a decade has passed in that universe, yet Vol. 11 still takes baby steps toward processing grief—here, with the question of whether it’s worth trying to use magic to bring someone back. Freya Marske’s A Power Unbound does just that in a passage that had me sobbing cathartically in a way I rarely expect to do in a romance, fantasy or otherwise.

This year I read more deeply into SFF short fiction, which is how I found Isabel J. Kim’s body of work. “Zeta-Epsilon” introduces us to a bonded brother-sister pair who are technically a human and an AI, but their identities are so interwoven that you could argue the reverse as well; I would love to read an entire series about their space escapades. Then there’s “Day Ten Thousand,” a profound take on reincarnation as the same pair of guys reenact their final confrontation across time and space.

–Natalie Zutter

I never do lists like this because I am far too indecisive to decide which book’s parameters sum to best but this year I do have a candidate: Moniquill Blackgoose’s To Shape a Dragon’s Breath.

Review at the other end of the link but the short version is “read this book.”

The Book that Wouldn’t Burn by Mark Lawrence. An infinite library! Twisty plot, believable characters I was rooting for, easter eggs for people who love books and pay attention. My favourite book this year.

If I did a conventional top five they have already been mentioned (Translation State, He Who Drowned the World, The Adventures of Amina -al-Sirafi, The Saint of Bright Doors, and Silver Nitrate). However, I’d like to do a shout-out to Mur Lafferty’s Chaos Terminal, which I haven’t gotten around to yet; I did read Lafferty’s Station Eternity this year, and I expect the follow-up to be as good as that novel.

Lavie Tidhar The Circumference of the World.

Wait, Appalachian gothic romance is a thing? Can someone tell me about this?

My favorite Fantasy book of 2023 was Fonda Lee’s Untethered Sky. It’s a superb story which features rocs hunting manticores, a nice break from the plethora of dragon books. Too often dragons are shapeshifters or act like dogs or cats – or in the case of Pern, sentient horses – but Lee’s creatures, while monstrous and magnificent, remain animals.

My favorite Science Fiction book published this year is Antimatter Blues by Edward Ashton, the sequel to Mickey 7. A satisfying conclusion to the arc which nonetheless leaves room for plenty more stories. It has the same feel as Bujold’s Vorkosigan series.

Godkiller, The Warden, Feed Them Silence are all very good, but didn’t quite hit my top.

(i tried to do a top 5, but then it became 10, and then it became 11, so. Ya know. It is what it is.)

But these are in no particular order, i loved them all very very much. (Really thought TSBIT was going to be my boty, Hell Followed With Us was last year – but oh it’s hard to not talk about all the others!)

The Spirit Bares Its Teeth Andrew by Joseph White

Camp Damascus by Chuck Tingle

Poet (Ghost Mountain Wolf Shifters #10) by Audrey Faye

Beholder by Ryan La Sala

Gryphon in Light (Kelvren’s Saga, #1) by Mercedes Lackey & Larry Dixon

Critical Role: The Mighty Nein—The Nine Eyes of Lucien by Madeleine Roux

Tress of the Emerald Sea by Brandon Sanderson

Starter Villain by John Scalzi

Godly Heathens (The Ouroboros, #1) by H.E. Edgmon

The Narrow Road Between Desires by Patrick Rothfuss

Bookshops & Bonedust by Travis Baldree

I read The Terraformers by Annalee Newitz to great satisfaction, but am even more impressed by The Ferryman, by Justin Cronin (https://www.goodreads.com/nl/book/show/61282437)

It has an intriguing first part about a society where the elite has no children, but gets rejuvenated, although with loss of previous memory, and then a surprising switch to another environment, and it poses all sorts of questions: off class, of justice, even if a design is needed for reality, and who or what should control it.