A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to be invited to a swanky location in London’s glamorous west end for anime distributor Manga UK’s 20th birthday party. Now for those of you outside the UK Manga may not be a familiar company, but on this side of the Atlantic it is a name synonymous with anime (and yes ‘manga’ being associated with ‘anime’ has caused decades of confusion). Originally founded in 1991 to distribute the movie Akira, it went on to not just release hundreds of titles theatrically and on VHS and DVD, but also to produce a legion of infamous dubs and even contribute financial backing to productions like Ghost in the Shell.

The party was fun, but a slightly unusual experience for me. Not just because us lowly anime bloggers don’t usually get invited to such fancy corporate events, but mainly because as I sat there—swigging free beer and munching free sushi—I found myself drifting away down memory lane.

One day in 1986, when I was about 12 years old, I wandered into Rainbow’s End, a comic and hobby store in the English city of Oxford. It’s not there anymore, but for years it was my main destination for fulfilling my childhood geek pleasures and relieving me of my pocket money. I can’t remember what I’d gone in for that day—maybe some Judge Dredd back issues or role-playing game supplements—but instead something else, something I’d never seen before, grabbed my attention.

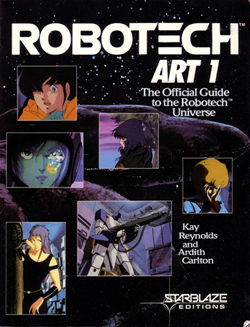

It was a large format art book, black cover with a star field in the background. There were several images on the front, mainly of exotic, unusually drawn looking characters — apart from one, that seemed to be of a massive robot holding an equally massive gun. And across the top, in a font that screamed futuristic adventure, was the word ‘ROBOTECH’.

In smaller text below that it said “The Official Guide to the Robotech Universe.” At that point I had no idea what Robotech was, apart from possibly the coolest word I’d heard in my young life, but the idea that there was a whole universe of it somewhere thrilled me. All other purchasing plans for that day were instantly dropped.

Robotech was a mystery to me because it was never broadcast in the UK, in fact Japanese animation in general has always been criminally under represented on TV here. Up until that point my only exposure had been The Mysterious Cities of Gold, Battle of the Planets (a re-dub and edit of Gatchaman) and Star Fleet, the UK TV version of Go Nagai’s ambitious puppet based show X-Bomber. Regardless, I soon found myself slightly obsessed with Robotech, pouring over the book’s character profiles, sketches and episode summaries for hours, despite never having seen even a few seconds of moving footage.

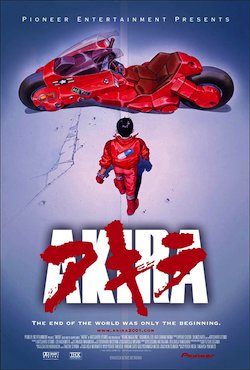

Just across the road from where Rainbow’s End used to be is a tiny arthouse cinema, the Penultimate Picture Palace. It’s still there, although its name has been shortened, and for decades it would be my main destination for fulfilling my film-geek pleasures. Five years later in 1991 a school friend and I turned up for a late night showing of a movie we’d heard rumours about. It was Katsuhiro Otomo’s animated classic, and Manga UK’s first release, Akira. We’d seen a clip once on TV that must have been barely two minutes long. Two minutes of motorbike chases, rioting and cyberpunk Japanese cityscapes. I can vividly remember us both stumbling out afterward into the cool night air, eyes-wide and speechless, Oxford’s crumbling, historic architecture fading into unimportance around us. Without resorting to hyperbole, that first viewing was a life-changing experience, akin to watching Star Wars, 2001 or Blade Runner for the first time.

Akira ripped through the British sci-fi fan community of the time like an expanding psychic explosion. Raised on the early movies of James Cameron, John Carpenter and Paul Verhoven like Aliens, Escape from New York and Robocop it made perfect sense to a generation of geeks obsessed with dark, violent science fiction. I remember queuing up at my local HMV on the day of release to buy the expensive, double VHS pack — and I wasn’t the only one. To this day people I meet, on finding out I have an interest in anime, proudly show me their own copies. Even if they never saw another anime film again, Akira still sits on their shelves. It’s still a favourite with my generation today, as sales this week of Manga UK’s blu-ray of Akira have proven.

Akira ripped through the British sci-fi fan community of the time like an expanding psychic explosion. Raised on the early movies of James Cameron, John Carpenter and Paul Verhoven like Aliens, Escape from New York and Robocop it made perfect sense to a generation of geeks obsessed with dark, violent science fiction. I remember queuing up at my local HMV on the day of release to buy the expensive, double VHS pack — and I wasn’t the only one. To this day people I meet, on finding out I have an interest in anime, proudly show me their own copies. Even if they never saw another anime film again, Akira still sits on their shelves. It’s still a favourite with my generation today, as sales this week of Manga UK’s blu-ray of Akira have proven.

Due to a coincidence of timing—or perhaps more truthfully part of some global zeitgeist—Akira would go on to have an even deeper impact. By the time it was released here techno music and rave culture was already infecting the UK in a fury of social change. Its dystopian urban landscapes and twisted, hallucinatory realities struck a note with the tribes of underground party-goers. As drug use suddenly became more widespread, t-shirts showing Kaneda popping pills suddenly became common place in clubs and warehouse raves, anime images started to grace party flyers, and Akira became one of the come-down movies of choice, VHS tapes worn thin after endless early morning viewings up and down the country.

What followed was a brief boom for anime in the UK. We were flooded with over-priced but poor quality VHS releases of Japanese TV and OVA shows. Largely misjudging what us newborn anime fans wanted, distributors bombarded us with anything that had a hint of sex, violence and a regurgitated cyberpunk vibe. While a lot of it was fun, many releases were given rushed, poor quality English dubs, with the scripts edited to include cursing not present in the originals, in order to force a 15 or even 18 classification and give the impression of ‘adult’ material.

Rapidly many of us lost interest, seeing works like Akira and Ghost in the Shell as one off artistic triumphs. Ironically it was the rave and techno scene that contributed to my own personal disinterest — with naïve dreams of being a professional DJ I had a vinyl records habit to feed, and no spare money to buy expensive VHS releases. For years I watched no anime at all.

That was until 1997, when I met my then new girlfriend. The daughter of an English father and a Japanese mother, on finding out I had an NTSC capable VCR she gave me a dusty old pirated VHS video of a film her grandparents had given to her on her last visit to Japan, at the age of eleven. She wanted to watch it again, as the only machine capable of playing it at her parents’ house had failed years ago, but I could sense a slight trepidation in her face as she handed it to me. It was a children’s film, she explained, and it might not be as good as she remembered.

The film was Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro, and despite the lack of any English subtitles or dub and the poor quality of the recording, for 90 minutes we both sat transfixed and enchanted. Suddenly I had a new obsession. Now with the Internet as my guide I started to hunt down as much information as possible, importing from the US any Studio Ghibli films I could find, and discovering the works of Otomo and Mamoru Oshii that had passed me by. Soon I was finding works by people I’d never heard of — Isao Takahata, Satoshi Kon, Makoto Shinkai, Shinichro Wattanabe, to name but a few. A fully-fledged anime fan was re-born.

As I get older, I can’t help but marvel at how things can often go full circle. In 2008 the two of us visited Tokyo, making a pilgrimage to the Ghibli Museum, which coincidently lies within walking distance from where my girlfriend’s grandparents still live, and where they first handed her that Totoro tape. Just last Christmas I received the boxset of the full Robotech Chronicles as a gift from my parents, now finally available freely in the UK. And as I sat there in that bar in London, beer in hand, I found myself watching clips from Akira projected on to a nearby wall. It’s been a strange journey and an exciting twenty years, and I’m glad that Manga UK took me along for the ride. Happy Birthday.

Tim Maughan lives in Bristol in the UK and has been writing about anime and manga for nearly four years, and consuming both for over twenty. He also writes science fiction, and his debut book Paintwork, a collection of near-future short stories,is out now. He also tweets way too much.