It begins with a roleplaying game, of all things, although it’s not called that precisely. It’s an immersive roleplaying environment, and our hero crashes it for him and his friends for wanting to go beyond its bounds and programmings, though not as a briefer. Rather, he is compelled by his innate drive and sense to seek and explore and burst the bounds that society and even this video game have placed upon him. And yet even this innocent exploration beyond boundaries causes change and crisis around him. It turns out to be a thematic strand in Alvin’s life.

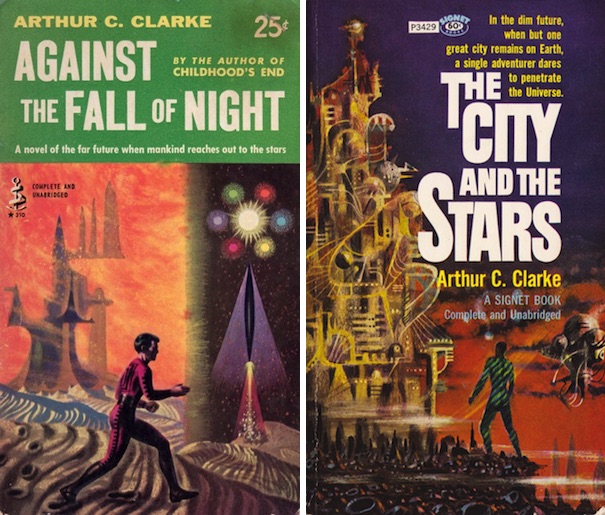

The City and the Stars is Arthur C. Clarke’s reboot of one of his earlier works, Against the Fall of Night. Both tell Alvin’s story.

Against the Fall of Night is somewhat shorter, with differences accumulating particularly in the latter portion of the story, but both stories, when compared, seem to influence and reflect on each other. Structurally, one can think of Clarke having written in the manner of improvising two musical fugues in the style of Bach to come up with Against the Fall of the Night and then The City and the Stars. Both share the central protagonist, Alvin, and the concept of a far-future, post-technological, seemingly utopian city, Diaspar, and his efforts to transcend its boundaries. Both make discoveries about the true state of affairs of Man and the universe, although they are significantly different, Against the Fall of Night being more lyrical and suggestive, The City and the Stars exploring the situation in more depth and with greater understanding.

In the telling, the variant fugues weave stories whose details can be intertwined and wrap around in one’s imagination if consumed in rapid succession. But that’s all right. These are novels where the slight plot doesn’t truly matter, where the thin characters are really not tremendously more than vehicles and conveyances. No, these are stories whose strengths lie in images, in themes, and most importantly, in ideas. And such ideas. The last city at the end of history, a sentinel seemingly with wasteland all around. A bloodless, passionate society which does try to create art and try to fight the stagnation at its heart, but it’s a beautiful and cold utopia, rendered memorably. This IS the ur-city of the future, one you can already see the matte painting backgrounds of in your mind’s eye. Reincarnation and regeneration of the city’s already long-lived population lends a sense of Deep Time that the two stories really make you feel, driving home the gulf of time that the city has existed, and how far it is from our own day. There are also computers with long-hidden agendas. Stellar Engineering. Psionics. And even an exploration of future religion.

Part of the timelessness of the books is due to the seamlessness of how the technology works in this novel and what is not described. We don’t get nuts and bolts descriptions of how the computers precisely work, how exactly how the inhabitants of the City are decanted again and again, or the propulsion and power systems (“We have gone beyond atomics” is one of the few descriptions we get, which means that the novels do not feel dated, even a half-century on. The sheer seamlessness of that technology means that the two novels serve as embodiments of Clarke’s Third Law (“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”) in action. These are the novels to point to when asking when and how Clarke applied his law in his own work. What’s more, thanks to the quality of the prose and the writing, being carried along by the story, I never feel the need to interrogate or examine that technology. It’s simply *there*.

And as the revelations of what our hero’s real place is in this world bring him outside of Diaspar, the outside world, the community of Lys, and the great universe beyond all reveal themselves. Here, Clarke shows the other half of the coin of what has happened to Earth and humanity. Diaspar is the technological utopia, where robots and machines provide an eternal recurring existence for all. In Lys, we get the Arcadian perspective, the community of telepaths and psionics who live shorter lives, lives tied to human relationships and the land. The dispassionate, cold, even asexual nature of Diaspar is strongly contrasted with the salt of the earth community of Lys. And yet even here, Alvin finds no definite answers, and is propelled to do something no human has done in ages—return to space.

And so many connections and points of inspiration can be traced from these novels to all corners of science fiction, making these the kind of books that you can use as a jumping-off point not only to read more Clarke, but many more other authors besides. One can go backward to Olaf Stapledon and Last and First Men, or go sideways and forward to Asimov’s Galactic Empire novels (and also End of Eternity), Gregory Benford (even aside from the fact that he wrote a follow-up to Against the Fall of Night), Michael Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time, Greg Bear’s City at the End of Time, Stephen Baxter’s Manifold series, Cordwainer Smith’s Nostrila novels, and Larry Niven’s A World out of Time. An Earth in fear of long-ago invaders returning someday is also a theme that Robert Silverberg picked up for his “Nightwings” cycle.

Brian Stableford’s classic The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places makes a cross-reference between Diaspar and the similar but differently post-technological Little Belaire, the settlement of John Crowley’s Engine Summer that I had not considered until I just picked up that reference book recently…but it makes a lot of sense. I haven’t even touched on the beauty of the often poetry-like prose, which could send you down time corridors ranging from Roger Zelazny to Rachel Swirsky and Catherine M. Valente. And the Jester in Diaspar seems to prefigure Harlan Ellison’s titular anarchist character in “’Repent, Harlequin!’ said the Ticktockman”.

If you want stories and films that resonate with Clarke’s stories, you can look to the 1970s, with both Zardoz and Logan’s Run showcasing funhouse versions of this sort of environment. The world outside the utopia in Zardoz is pretty brutish, and the people inside are *all* bored, eternally young unless they act out against society, and unable to die, being reborn again and again. It takes someone who has been almost genetically programmed for the task to break their cycle. Logan’s Run, with its saccharine utopia where everyone dies at 30, is another bottled-up world where again, the protagonist deals with the fundamental problem of society by fusing it with the world outside, by force. To cite a slightly more recent example, given Alvin’s ultimate nature, one could argue that Neo in The Matrix is also seemingly inspired by him, as envisioned in the movies past the first.

And yet in all of these stories, just like in Clarke’s novels, the outside world alone and what is to be found there is not the answer. It takes the Apollonian *and* the Dionysian in order to make a healthy society and a balanced world. That’s a key message in these two works—in the end, both Diaspar and Lys are imperfect, flawed places. Our narrator’s journey, as straightforward as it has been on the surface, has served not only to illuminate himself, his real nature and his character, but has led to the revelation that both of the remaining estranged societies on Earth are imperfect places that desperately need a dose of each other in order for Man to face the universe he retreated from, long ago. And both of these works—for all their similarities, differences, and echoes—are beautiful, and well worth your time.

An ex-pat New Yorker living in Minnesota, Paul Weimer has been reading sci-fi and fantasy for over 30 years. An avid and enthusiastic amateur photographer, blogger and podcaster, Paul primarily contributes to the Skiffy and Fanty Show as blogger and podcaster, and the SFF Audio podcast. If you’ve spent any time reading about SFF online, you’ve probably read one of his blog comments or tweets (he’s @PrinceJvstin).