It seemed absolutely natural to me, when I first opened a new document with a blank page, that a book set in space in the far future could—maybe should—involve mindmelding.

In retrospect, this was not a normal assumption to start writing a book with.

In my defence, there is a long history of mindmelding and other psychic shenanigans in the space opera genre. The element features heavily in Hugo-winning modern science fiction like Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie and Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee; classics like Dune and Star Trek; every flavour of story in between. Soulbonding is also a trope with a long history in fandom and SFF romance, generally romantic but sometimes platonic, with mindreading and shared feelings in infinite combinations.

A mind-bond is the ultimate narrative device. So much of fiction is about the knowing of people—do we know ourselves? Can we know others? What parts of ourselves do we want to keep away from the merciless light of scrutiny? A mind-bond is a way of being known when maybe you would rather not be known. Of knowing others. Of humanising a stranger, a friend, an enemy; and at the same time transcending that foundation stone of humanity that is the one-to-one mapping between a mind and a body.

I spent some time tracking back the slippery slope that got me to love the idea of mindmelding in speculative fiction. The first culprit I can recall is Tamora Pierce’s Circle of Magic books (not sci-fi, but bear with me). In those, four misfit teenage mages find out they can talk to each other in their minds, something that gets tricky when they age out of being a close group of preteens and start to grow apart and become more complicated. 11-year-old me was sold: immediate psychic communication makes everything much more interesting.

The next books I found were Anne McCaffrey’s work. Some of you reading have just had a strong reaction to that and to you I offer a high five and the urge to get into the McCaffrey discussion of ‘did that actually happen in one of her sci-fi books or was that a fever dream’. I wouldn’t hugely recommend picking up a random McCaffrey without reading some of the discussions around her work but, the thing is, Anne McCaffrey had the wildest ideas about psychics in space. What about a dragon you could mindmeld with who was also sort of a space construct (the long-running Dragonriders of Pern series)? What about a main character who was psychically linked to crystals (Killashandra)? What about human minds built into ships who kept falling in love with their crewmembers (The Ship Who Sang)? What about a psychic unicorn human hybrid in space with a healing forehead horn who kept rescuing Dickensian orphans (I might be getting into fever dream territory there but I’m pretty sure that one happened). McCaffrey’s ideas had everything. When I read her work, I was pretty sure just normal humans mindmelding in space was the standard, safe option.

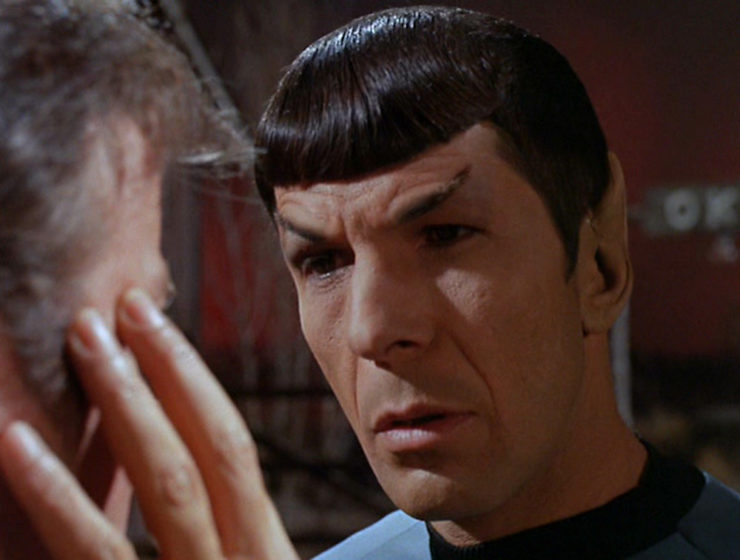

At this point my girlfriend requires me to reference the most famous mindmeld in space–Star Trek: The Original Series, where Captain Kirk and his telepathic alien friend(?), Spock, mindmeld to retrieve Kirk’s memories (and a host of other reasons later). I will now hand in my sci-fi card because I have only seen one episode and it wasn’t even that one. But the history of this is important, right back from the 1960s, and it feeds many of the other things I talk about in this article in visible and invisible ways (this could be a whole discussion in itself, but for now please direct comments to my girlfriend who would like you to know she has a 60-minute talk with slides upon request). But intimacy—connection—understanding—the ultimate breaking of boundaries: all of these things, the use and misuse of them, are what we explore when we write the experience of a mind leaving its body and touching another.

And sci-fi has, of course, explored the dark side of soulbonds. Both Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee, in which a low-ranking soldier finds herself thrust into leading a horrific war, and The Stars Undying by Emery Robin, which reenacts Anthony and Cleopatra on an interstellar scale, explore the concept of a great charismatic mind that has been preserved, or translated, and now has a mind-bond with the protagonist of the book. Immortality, but tied to a stranger. Psychic powers—the ability to communicate with, or act through, someone else—are narratively fascinating because they are in one way a limitation of freedom: your thoughts are not your own, and neither are theirs. If you take action, it must be with someone else’s hand. You had an identity; it is no longer inviolable. Who are you, when you are also someone else?

Gideon, Harrow and Nona the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir revolve around the central question: if the option to absorb someone’s mind gave you power, would you do it? Should you do it? If you love each other, if you would do anything for each other, does that make a difference? The series then proceeds to take its large cast and unpick that question in an astonishing variety of awful ways, exploring love, power and villainy in equal doses. I adore these books wildly and immeasurably. Muir was asked to pick between going hard and going home and immediately lost her residential address and set fire to her bus pass, and I admire her for this.

With the two characters in my book Ocean’s Echo—a frenetic socialite and a dutiful lieutenant—I had plotted out everything up to the first mind-meld. The power struggles, the enmities, the tentative alliance, the long and gleeful con where they fake it. What I discovered was the moment they merged minds, I suddenly had lots to say about mindmelding, almost more than would fit on the page. What does it mean, to know the ultimate humanity of others in a military environment that relies on you to conform? What does it mean, to be partly someone else?

And if you love each other, does that make a difference?

Buy the Book

Ocean’s Echo

Everina Maxwell is the author of the new space mindmelding book Ocean’s Echo and the ALA Alex Award-winning Winter’s Orbit. Everina’s hobbies are collecting books and killing houseplants.