Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

This week, we’re reading Hagiwara Sakutarō’s “The Town of Cats,” first published in 1935 as Nekomachi; the English version in The Weird was translated by Jeffrey Angles and originally appeared in Modanizumu in 2008. Spoilers ahead.

“When the inhabitants did anything—when they walked down the street, moved their hands, ate, drank, thought, or even chose the pattern of their clothing—they had to give painstaking attention to their actions to make sure they harmonized with the reigning atmosphere and did not lose the appropriate degrees of contrast and symmetry with their environs.”

Summary

Narrator, once an avid traveler, no longer has any desire to explore the physical world. No matter where one goes, one finds the same dreary towns, the same dull people leading humdrum lives. He used to travel much in his “own personal way,” via morphine or cocaine-induced hallucinations. Then would he “adroitly navigate the borderline between dreams and reality to play in an uninhibited world of my own making.” It was a world of brilliant primary colors, of skies and seas always clear and blue as glass, where he’d wander through wetlands inhabited by little frogs or along polar coasts where penguins dwelt. These ecstatic voyages, alas, took a toll on his health, which he now tries to restore with regular walks.

A fortunate misfortune allows him to satisfy his “eccentric wanderlust” without drugs. Narrator, you see, can lose his way even in his own neighborhood. His family insist a fox has bewitched him. Science might explain his problem as a disturbance of the inner ear. One day he entered a street from a new direction, to find it transformed from a row of tawdry shops to a beautiful and utterly unfamiliar little space! Then, as suddenly as the extraordinary manifested, it returned to the ordinary street narrator knew.

He understands that a perspective shift can reveal the “other side” of a place. Perhaps any given phenomenon has a secret and hidden side—an existence in the fourth dimension. Or maybe he’s just delusional. Being no novelist, all he can do is write a “straightforward account of the realities I experienced.”

Narrator sojourns at a hot spring resort in the mountains of Hokuetsu. Autumn has come, but he lingers, enjoying walks along the back roads and rides on the narrow-gauge railway that runs to the nearest town of any size, which he’ll call U. He also enjoys listening to the folklore of the region, especially stories about the “possessed villages” – one where the people are possessed by dog-spirits, the other where people are possessed by cat-spirits. These denizens are privy to special magic, and on moonless nights hold festivals forbidden to outside observers. One of these villages was supposedly close to the hot spring; now deserted, its inhabitants may continue to live a secret life in another community.

Country people can be stubbornly superstitious, narrator thinks. Probably the “dog and cat people” were foreigners or perhaps persecuted Christians. Yet one must remember, “the secrets of the universe continue to transcend the quotidian.”

Pondering these things, Narrator follows a path that parallels the rail tracks to U—until it doesn’t, and he finds himself lost in the woods. At last he discovers a well-trodden path leading down from the mountain crest. It must end at least in a house.

It ends, joy, in a full-grown town—a virtual metropolis of lofty buildings out here in the remote mountains. Narrator enters through dark, cramped pathways but emerges into a busy avenue. The city has the beauty of conscious artistry weathered to an elegant patina. Flowering trees, courtesans’ houses breathing music. Western houses with glass windows. Japanese inns and shops. Crowds of people in the streets, but no horses or carriages. No noise. The crowds are elegant and calm, and graceful, with harmonious, soft voices. The women’s voices have a particularly tactile charm, as of a gentle stroke passing over one’s skin.

Bewitching, but narrator realizes the town’s atmosphere is artificial. Maintaining it requires “tremendous effort, made all the nerves of the town quiver and strain….the whole town was a perilously fragile structure [dependent]….on a complex of individual connections….[Its] plan….went beyond a mere matter of taste. It hid a more frightening and acute problem.”

The serenity of the town now strikes narrator as “hushed and uncanny.” Premonition “the color of a pale fear” washes over him. He smells corpses, feels the air pressure rise, electrified. Buildings seem to distort. Something strange is about to happen!

What is so strange about a small black rat dashing into the road? Why should narrator fear it will destroy the town’s harmony?

In the next heartbeat, great packs of cats fill the roads. Cats everywhere! Whiskered cat faces in all the windows! Cats, cats, cats, cats, cats, cats, and more cats until there’s nothing else in the world! Narrator closes his eyes, opens them to a another reality—

Which is the town of U, same white clay streets, dusty people, midday traffic, clock shop that never sold anything.

Has he descended the mountain and, entering U from a novel direction, succumbed to his defective semicircular canals? Or did he slip into the fourth-dimensional backside of U and find one of the possessed villages of legend? Narrator is firm: “Somewhere, in some corner of the universe, a town is inhabited solely by the spirits of cats. Sure enough, it does exist.”

What’s Cyclopean: Matching Lovecraft for alarming architecture, the buildings of Alt-U “distended into bizarre, turretlike forms” and “roofs became strangely bony and deformed like the long, thin legs of a chicken.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Rural communities are full of “primitive taboos and superstitions.” Many superstitious tales reflect more mundane biases—for example, against foreign immigrants quietly carrying on old religious practices and food restrictions.

Mythos Making: Perhaps this tale will lead readers to imagine a fourth dimension hidden behind the world of external manifestation.

Libronomicon: In trying to decide on the reality of his experiences, Narrator quotes the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Readers dubious about the whole fourth dimension business may think this tale “the decadent hallucinations of an absurd poet whose nerves have been shattered by morphine addiction.”

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Ruthanna’s Commentary

A walk in strange lands, a town named U—, cats whose whims ought not be thwarted… are we in Ulthar? Not this week. Tempting as it is to find a connection between Lovecraft’s 1920 story and Sakutaro’s 1935 piece, I’m having trouble coming up with a way that a copy of Tryout makes it to Tokyo. Sometimes a coincidence of story elements is merely a hint at the ominous patterns that lurk beneath reality’s tissue-thin veneer.

It’s too bad that there’s no opportunity for such a connection, because it seems like Sakutaro—Bohemian, experimental in style, and deeply embedded in his own country’s small press scene—might have enjoyed Lovecraft’s efforts. And Lovecraft might have benefited from knowing that some of those scary non-Anglos were busy putting out basement-press literary journals full of new poetic forms. He certainly would’ve enjoyed this week’s selection, even if he would’ve objected to demonic cats on principle.

Though the cats this week may be merely the surface form of some greater phenomenon, like hogs or frogs. “The Town of Cats” is as much “From Beyond” as Ulthar. Something lies beneath the surface of everyday perception. Unless it doesn’t—and like Lovecraft, Sakutaro is ambivalent about whether that would be a good thing. His narrator starts with all the reasons why his perceptions shouldn’t be trusted. His drugs aren’t there for mood-setting, like Poe’s, but to provide a disclaimer. He’s not the most credible of reporters, and besides, his glimpses of magnificent places have always turned out to be a mere side effect of his poor sense of direction. And maybe a problem with his inner ears. I have a friend with inner ear problems. They give her trouble on stairs; they’ve never resulted in visits to the slip-side of reality.

Narrator also assures us that he no longer feels the desire to visit exotic climes, whether by train or cocaine. He’s learned that real life is dull everywhere, that clerks and bureaucrats are all alike. (If you travel to exotic climes and then go watch clerks doing paperwork, the quality of your vacation is not anyone’s fault but your own.) But what’s truly delusion? Is the carefully choreographed town, fallen to cats, really illusion? Or is the narrator’s professed ennui the true false perception? Philosopher dreaming of being a butterfly, or butterfly dreaming of being a philosopher? At the last, our narrator comes down on the side of the latter. It’s not clear whether this is an ontological judgment, or an aesthetic one. Randolph Carter, who chose the Dreamlands without ever doubting his adult boredom with the everyday world, could have done with a little of this ambiguity.

The town itself, pre-cat, is one of the more subtle and extraordinary fears we’ve found in this Reread. No gugs required, just the unspoken and unspeakable tension of a society full of people who know how fragile is the beautiful pattern of their lives, how inevitable its collapse. This is a theme about which Lovecraft was distinctly unsubtle; for him the fragile and vital pattern was Anglo civilization, a set of delusions standing between “us” (the right “us,” of course) and getting eaten by incomprehensible eldritch abominations. For Sakutaro, maybe traditional Japanese civilization, which was in fact about to be turned on its head by the violation of traditional patterns? The existential dread around which he wrote this story, reflected in his larger body of poetry, seems as much a product of the shaky period between World Wars as Lovecraft’s oeuvre.

Any time travelers want to try and get these guys in a room together?

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Anne’s Commentary

It’s the dates,

The near-perfect overlapping of the years,

That strike me: For Hagiwara, 1886-1942,

For Lovecraft, 1890-1937.

They wrote poetry at the same time, but it was not only

The girth of a planet that separated them,

The barrier of language that might have deafened them,

Each to the other.

Howard, you old sonneteer, you classicist,

Would you have read the work of a hard-drinking bohemian who

Went around liberating already FREE verse from its traditional bonds?

Maybe. Who knows. Sometimes you surprised us.

The near-perfect overlapping of years, though.

Forget about the writing. They dreamed together.

They dreamed together, and I’m sure

Their dreamlands overlapped at one vulnerable border, or several.

This Cat Town narrator, that’s Sakutaro, I’m saying,

And Randolph Carter is Howard, close enough for poetry work.

Between the one’s little marshland frogs and the marshes where Ibites dance, horribly

Only a thin dimensional tissue stretches,

And so too between the primary-hued penguins of one’s polar coast and the other’s

Blind bleached birds not quite the lords under mountains of madness.

Now, between Cat Town and at Ulthar, I think,

There’s no tissue at all.

Cat-spirits and cats-in-the-flesh may pass back and forth;

They have their disagreements about whether it is meet for high-minded cats

Ever to stoop to human form, however illusionary,

But they can put those differences aside for the good of Universal Felinity.

And at the very line where Cat Town teahouse merges into Ulthar inn,

Sakutaro and Howard sit now, as free versifiers as versifiers can be,

And Howard confesses he’s become quite fond of a particular poem by his opposite.

He smiles. He must have been the bedridden man in the last line,

And the black cats, his favorites, must have perched patient on the roof-ridge,

Waiting to jump him home.

“Cats,” by Hagiwara Sakutarō

Black-as-can-be cats arrive a-pair,

Up on a rooftop, a plaintive eve,

And on the tips of their pointed tails hung

A wispy crescent-moon, looking hazy.

‘O-wah, good evening,’

‘O-wah, good evening.’

‘Waa, waa, waa.’

‘O-wah, the man of this household is bedridden.’

Next week, more creepy dreams, and more cats, in E.F. Benson’s “The Room in the Tower.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

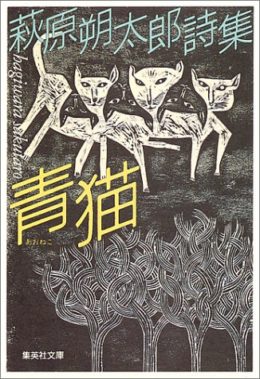

Your picture shows the poetry collection aoneko 青猫 (blue/green/black cat), not the novel nekomachi 猫町 (cat town).

This was an interesting piece. Going in I thought this was going to be something like Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence story “Ancient Sorceries”. Then it clearly wasn’t and then it looked like it might be again, but finally wasn’t. That’s a lot of seesawing in a fairly short story. He kept building tension and then releasing it in rather harmless ways.

Coming upon a familiar place unexpectedly from an unusual direction can be disorienting. It’s happened to me. I wouldn’t blame inner ears or demonic foxes. It’s just our brains being weird. Seems like the sort of thing Ruthanna might study.

Sometimes a coincidence of story elements is merely a hint at the ominous patterns that lurk beneath reality’s tissue-thin veneer.

When it’s time to railroad, wee build railroads. When it’s time to create towns full of cats…….

It’s truly fascinating to get a non-Anglo-American perspective on the eldritch! For more, I would recommend that you check out the work of the renowned early-20th-c. Russian writer Leonid Andreev, some of whose grotesque short stories are very strongly akin in atmosphere to Lovecraft’s work. Fascinatingly, we know that Lovecraft actually read some of his stories in translation, so he may very well have been a direct influence. As for which story to review—I’d strongly recommend “Lazarus”, a gorgeously disturbing retelling of the Biblical story in which the protagonist comes back as a representative of the inconceivably alien reality beyond death. It’s short, and easily accessible for free online in translation.

#4: pure existential terror, just walking around. There’s an unanswered question in the story which I wondered about after I read it: what exactly was Jesus, that he would inflict Lazarus upon Palestine?

(I recall at least one other “Lazarus goes wrong” story, but it was just a regular zombie).

5: Well, Lovecraft does present one child of God and Man, born to do the will of His Father on Earth….

Sōseki’s wagahai ha neko dearu 吾輩は猫である (I am a cat) is a more likely influence on Hagiwara than Lovecraft’s cats.

If I’m remembering right a town of cats, or rather a story about a town of cats, features in Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, though it would take me a while to dig through and find it. It’s not this story, but it seems to me it might be alluding to or “rhyme” with it.

Does this bring Millions of Cats to anyone else’s mind?

It reminds me in a weird way of The City and the City By China Miéville

Morgan Hunter @@@@@ 4: Okay, I’ll bite–would you mind sending along a link? You intrigued me enough to go looking, and all I could find was long outtakes of some longer work that didn’t appear to be the right thing… I wander lost in the stacks at Miskatonic, searching for the forbidden volume.

@11

It’s been a while since you asked and maybe you won’t ever see this, but it can be found here. Morgan Hunter very slightly mispelled the author’s name, which may be why you couldn’t find it?

Jester @@@@@ 12: Thank you!